Key Points

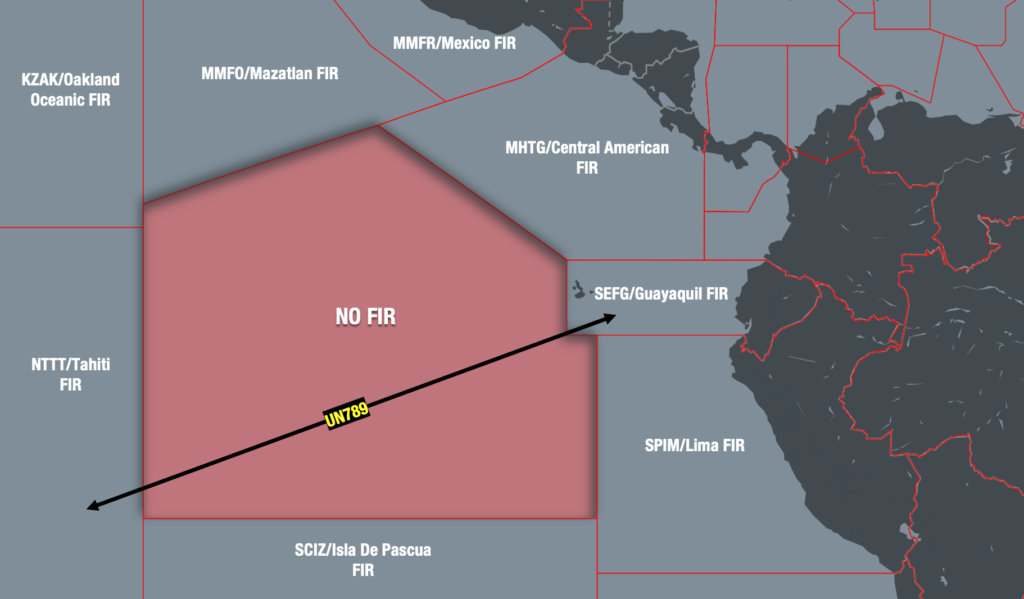

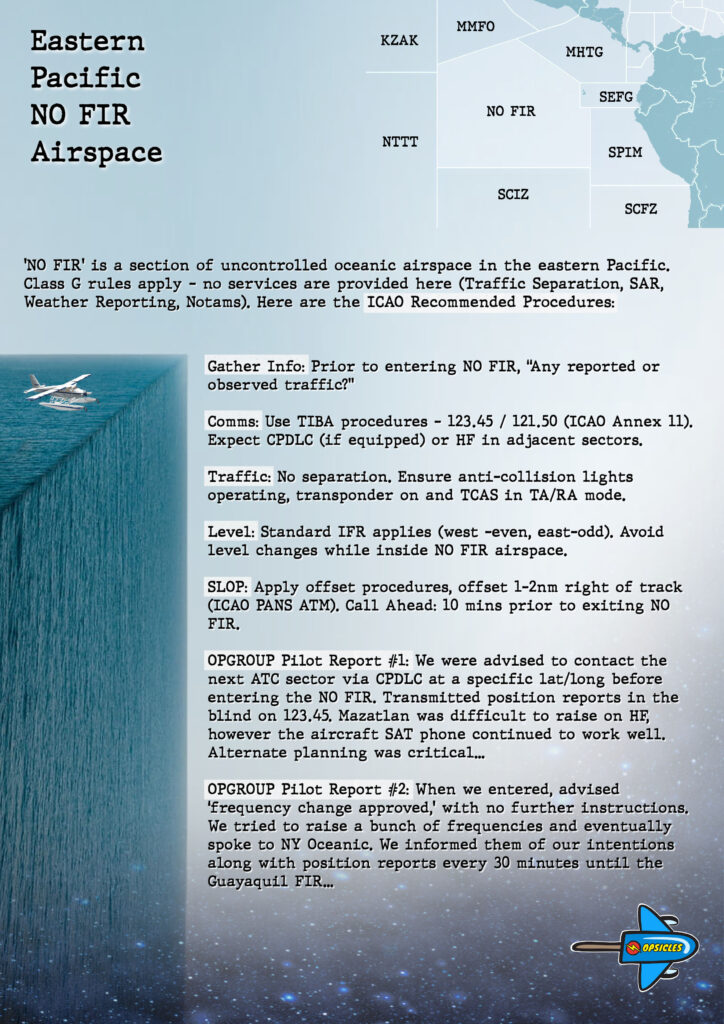

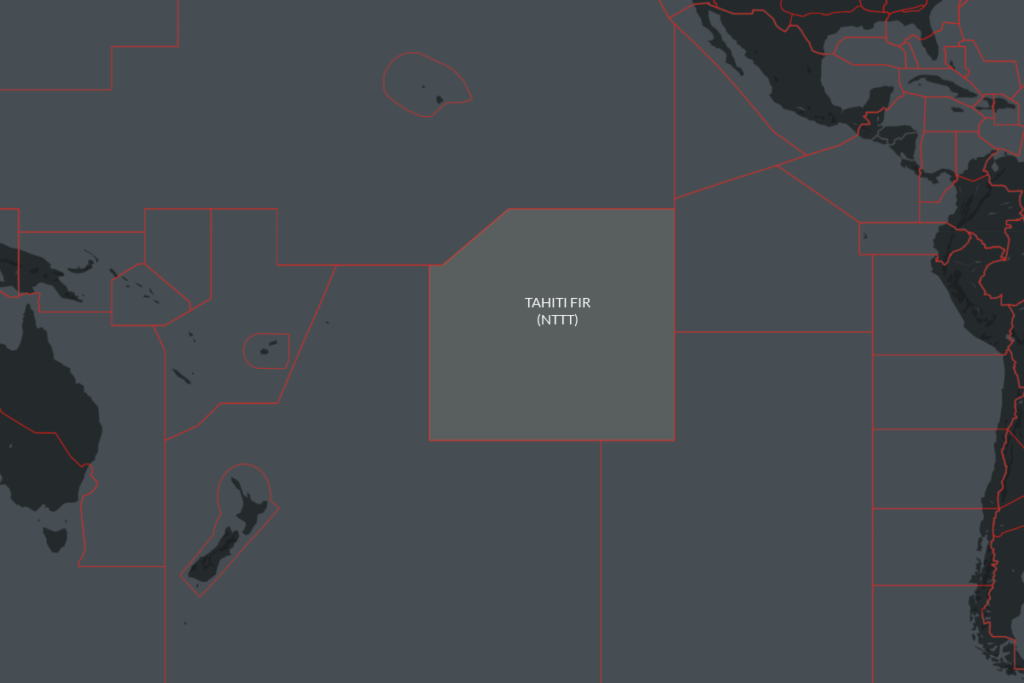

- ‘NO FIR’ is a section of uncontrolled oceanic airspace in the eastern Pacific.

- Class G rules apply – no services are provided here (Traffic Separation, SAR, Weather Reporting, Notams).

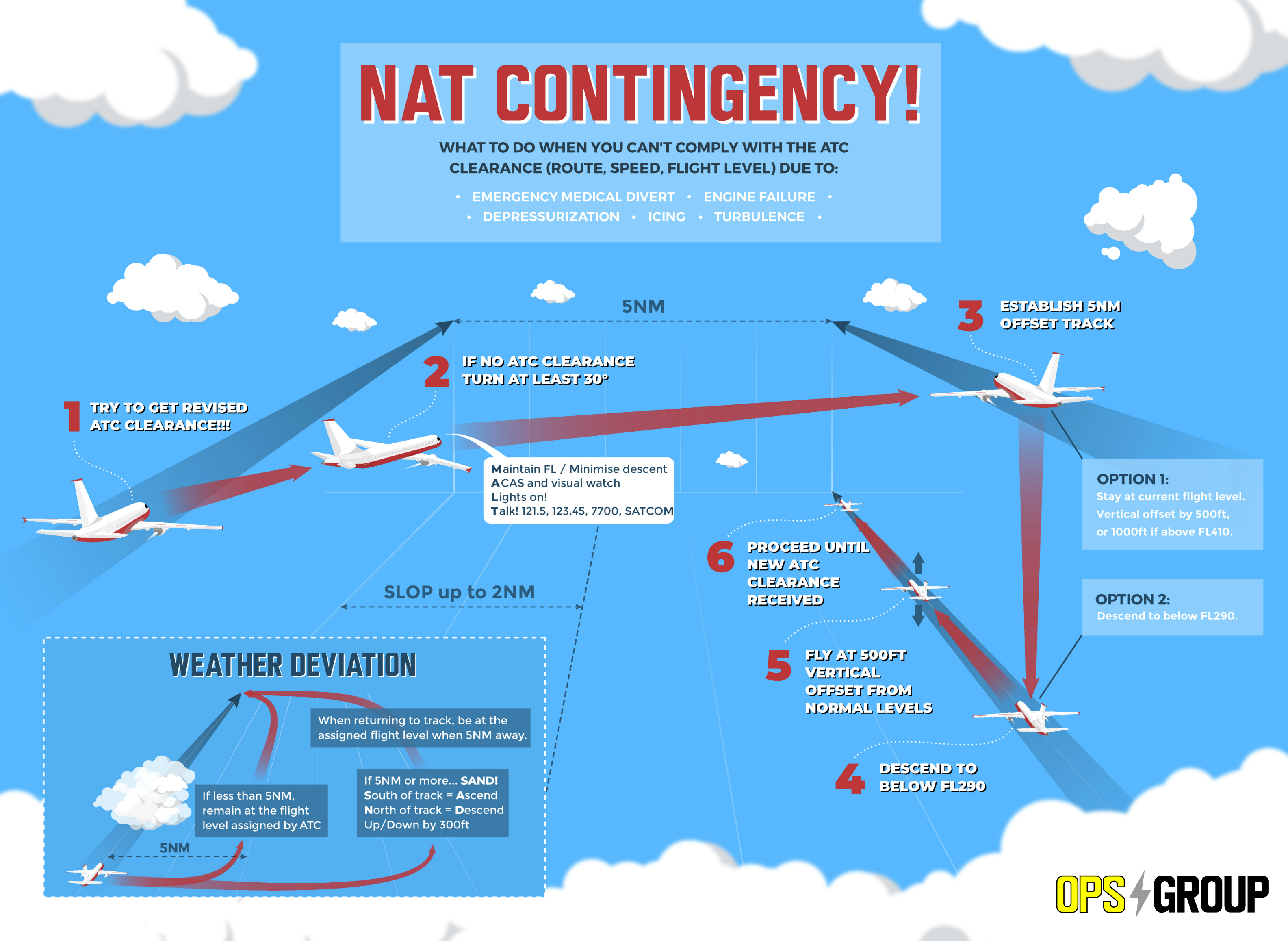

- There are some ICAO Recommended Procedures: Contact ATC, use TIBA Procedures, turn on all lights, keep squawking, SLOP, and fly standard levels.

- Download the OPSICLE below for a summary of the procedures.

‘NO FIR’ at the edge of the world

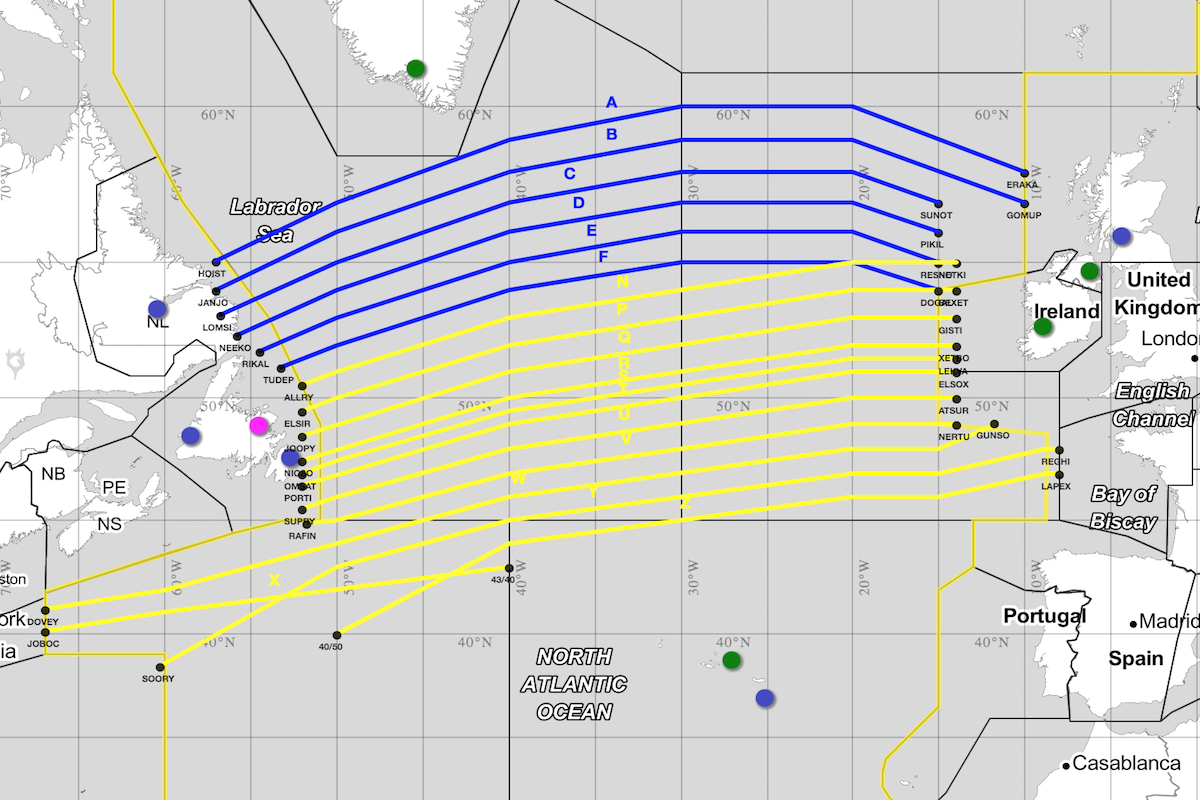

Well off the coast of Peru in the Eastern Pacific sits a large chunk of oceanic airspace known simply as ‘NO FIR.’ As the name suggests – it is completely unassigned. No ATC agency is responsible for it.

You may not have heard of it, because in almost all cases operators simply avoid it. There are just no procedures out there. And when attempting to find some, more questions are raised than answered.

The problem is that avoidance is beginning to cost time and money. With the establishment of ultra-long-haul routes, and aircraft capable of flying them, fuel is becoming increasingly critical. Especially when you consider that in some case ETOPS certification has now reached a whopping 370 minutes – that’s six hours.

And so OPSGROUP is often asked – how exactly can we operate directly across it? We didn’t know either, so we reached out to ICAO for some answers.

Where can I find the procedures?

This may come as a surprise, but there are none. Because no state is responsible for the NO FIR airspace (yet), there is no AIP to reference.

Until ICAO can successfully delegate this laborious task to adjacent countries, the standard ‘rules of the road’ apply – and none of them are specific to this particular piece of the high seas.

There is some provisional guidance out there, but it is just that – provisional. It is based on a 2019 project to subdivide the NO FIR airspace into pieces managed by Peru, Ecuador, Tahiti and the COCESNA states. This has yet to happen, and was stalled by Covid. ICAO advise the project has been revised but will take more time to implement. Until then, no one is home.

Best practice

So, how do we cross the NO FIR airspace without procedures? We need to rely on best practices instead. Here is what ICAO suggested to OPSGROUP, and it begins with a caution:

No one is responsible for it. It is important to understand the impact of this. There will be no traffic separation, SAR services, weather forecasting or even Notams. You will also need to make sure your insurer is happy for you to traverse this kind of airspace.

There’s a lot of ocean out there – careful contingency planning is needed to mitigate the risks of crossing NO FIR airspace.

Having made the decision to enter however, ICAO recommends the following:

- Use the information available to you. Before you enter the NO FIR airspace, ask controlling ATC the following question (keeping in mind that English may not be their first language)…

“Is there any known, or observed traffic?”

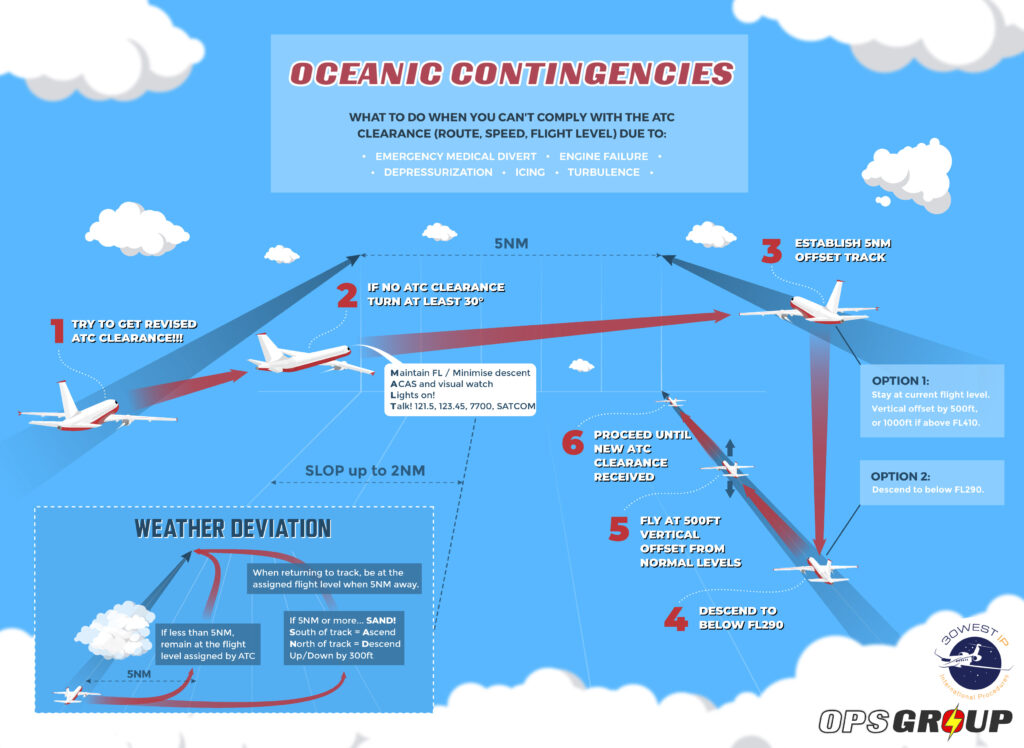

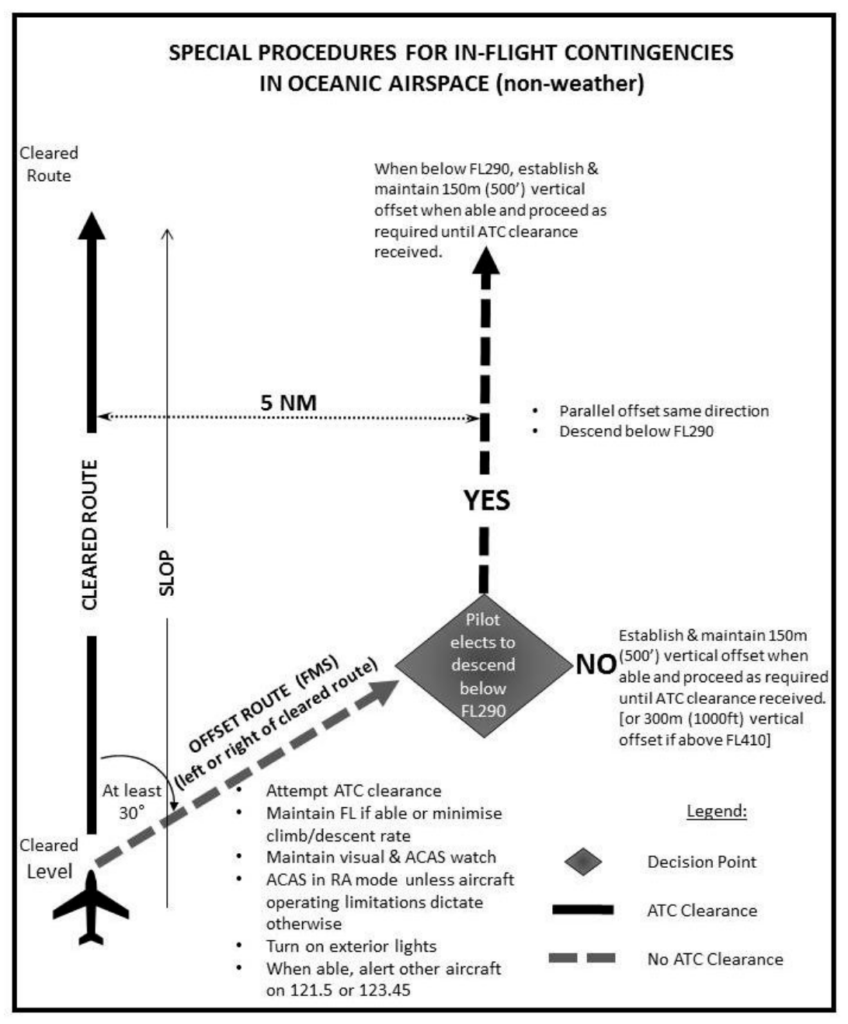

It is possible they’re aware of preceding traffic ahead, or are expecting some to exit. Even partial info, is better than none at all. - Use TIBA procedures. Yes, they’re technically for ‘contingencies,’ but the principle remains the same – hear and be heard. You can find those procedures in ICAO Annex 11. What frequency? There isn’t one published for the NO FIR airspace and so ICAO suggests using chat (123.45) or guard (121.5).

- Be Seen. Turn on all anti-collision and navigation lights, just in case.

- Keep Squawking. Use your transponder and TCAS TA/RA function at all times.

- SLOP. Follow Strategic Lateral Offset Procedures to further separate you from oncoming traffic. In other words, intentionally deviate up to 2nm right of your airway. You can find those procedures in ICAO PANS ATM, or ICAO Circular 354.

- Fly Standard Levels. Stick to even levels heading west, and odd levels heading east. Also avoid changing levels inside the uncontrolled airspace unless it is dangerous not to do so.

- Call Ahead. At least ten minutes before exiting the NO FIR airspace, call ahead and give the next ATC sector a head’s up you’re coming.

What not to do

Rely on adjacent agencies to take care of you anyway.

The most common misconception out there seems to be that the KZAK/Oakland Oceanic FIR will provide some emergency assistance via CPDLC.

When we reached out to them directly they advised this may be the case for some aircraft transiting the adjacent MMFO/Mazatlan FIR, but this is not the case for the NO FIR airspace – as far as they are concerned, there is no log-on available or any other services available.

Operator reports

So that’s what written on the back of the packet, but what about intel from pilots who have recently flown through it? OPSGROUP reached out to members, and received these reports on what to expect:

OPSGROUP Member: …we were advised to contact the next ATC sector via CPDLC at a specific lat/long before entering the NO FIR. We transmitted position reports in the blind on 123.45. Mazatlan was very difficult to raise on HF, however the aircraft SAT phone continued to work well. Alternate planning was critical. We flew through in day visual conditions, and so weather was easy to see and avoid…

OPSGROUP Member: …when we entered, we were simply told ‘frequency change approved,’ with no further instructions. We tried to raise a bunch of frequencies and eventually got in touch with NY Oceanic (randomly). We just informed them of our intentions along with position reports every 30 minutes until we entered the Guayaquil FIR. I’ve never been able to find further instructions on how to operate in this airspace…

There is no magic bullet

The Pacific’s NO FIR airspace is useable but with careful consideration. The challenges of crossing it can be mitigated, but only with solid contingencies in place.

ICAO’s guidance above is a solid starting point, however it is up to individual operators to decide whether the commercial reward outweighs the potential risks.

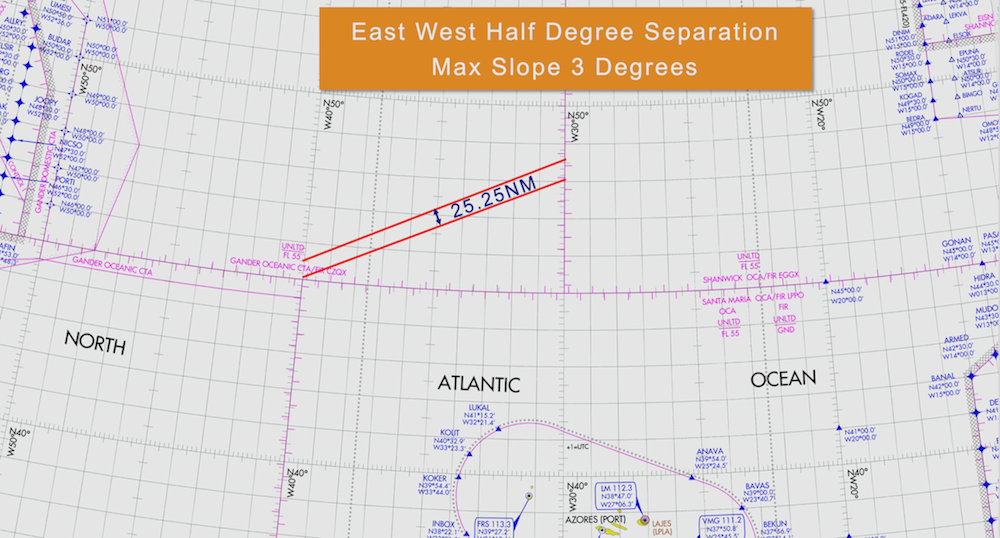

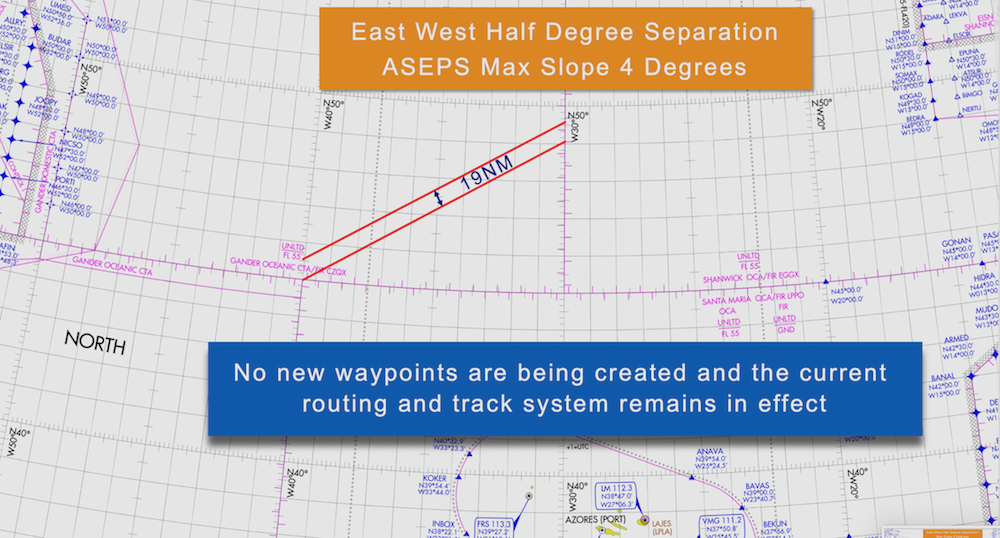

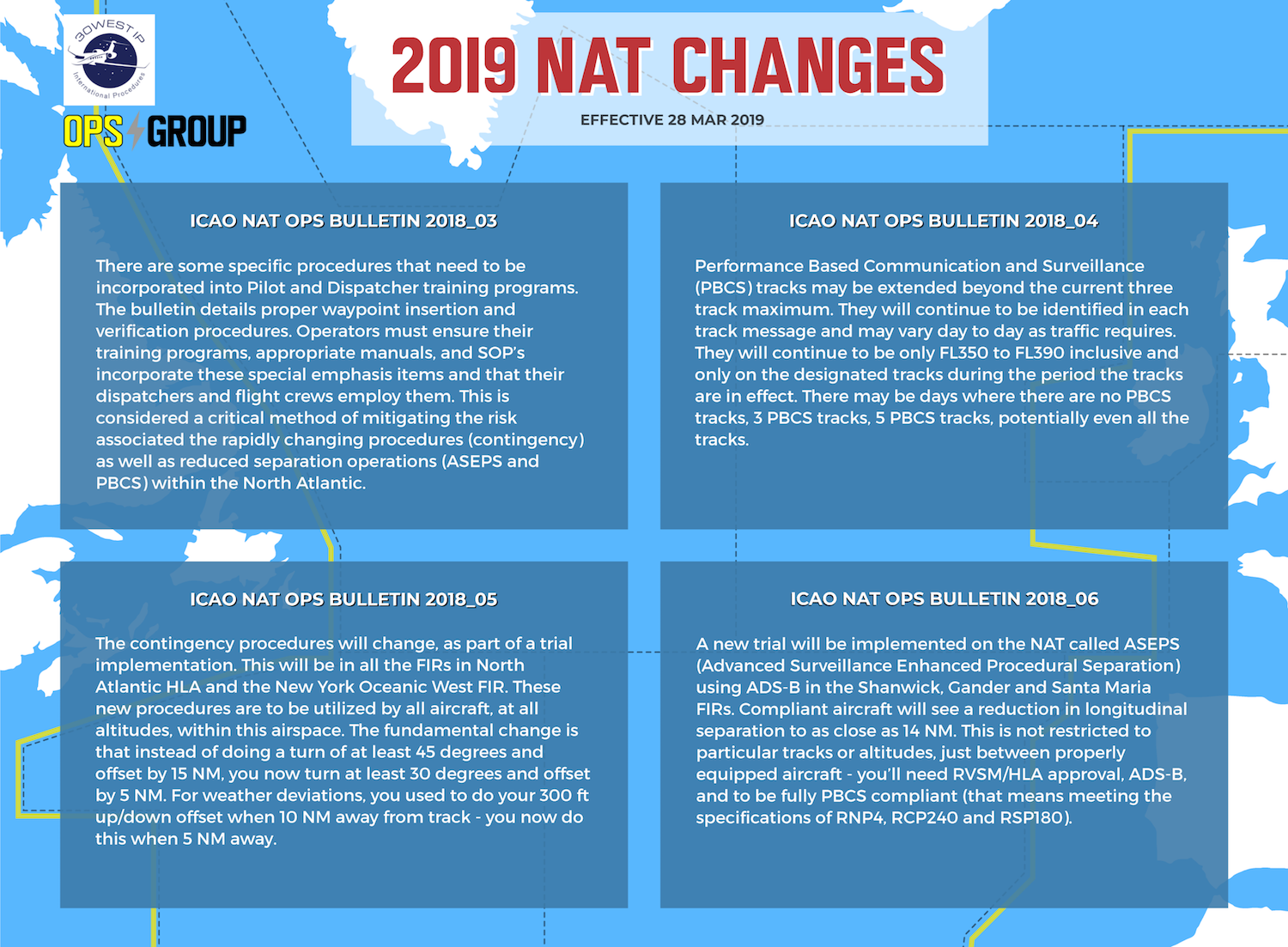

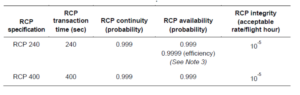

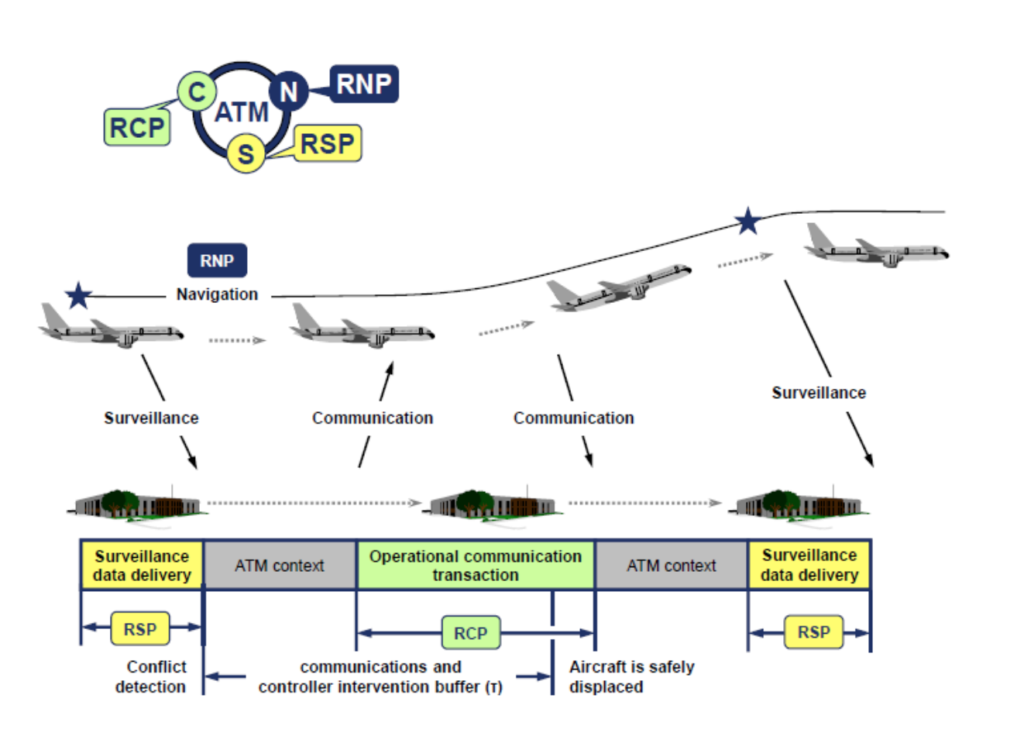

There are two key buzz words, so let’s define them. They are interlinked with RNP – Required Navigation Performance.

There are two key buzz words, so let’s define them. They are interlinked with RNP – Required Navigation Performance.

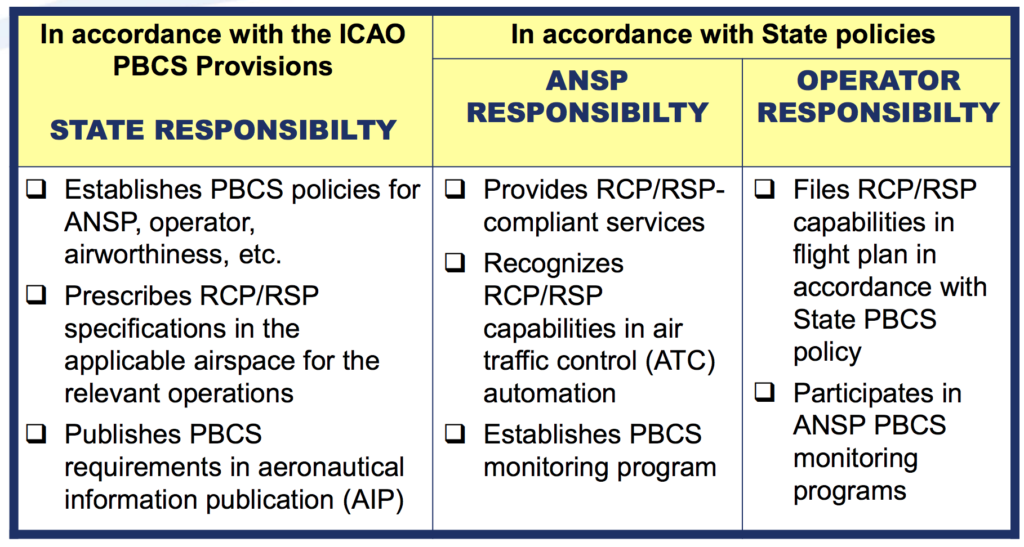

Requirements vary from state-to-state on the exact procedure for obtaining approval. It’s important to note that not all aircraft are automatically PBCS ready (refer to your aircraft manufacturer and your airplane flight manual).

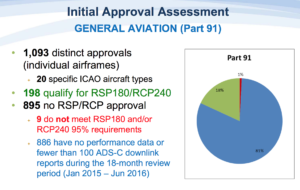

Requirements vary from state-to-state on the exact procedure for obtaining approval. It’s important to note that not all aircraft are automatically PBCS ready (refer to your aircraft manufacturer and your airplane flight manual). Ok this is the funny part of this story. The short answer, probably not.

Ok this is the funny part of this story. The short answer, probably not. If you do not have RCP240/RSP180 approvals you will always have the larger separations, e.g. 10-min, applied, and not be eligible for the lower standards in cases where it may be beneficial.

If you do not have RCP240/RSP180 approvals you will always have the larger separations, e.g. 10-min, applied, and not be eligible for the lower standards in cases where it may be beneficial.

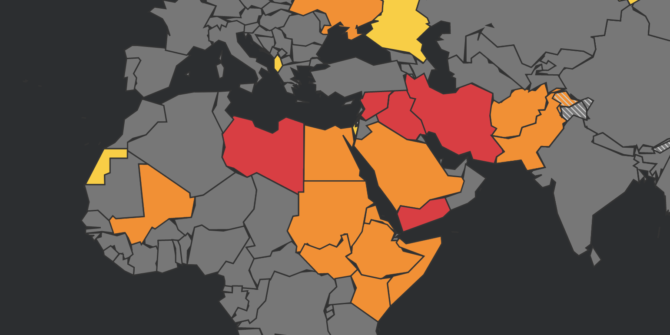

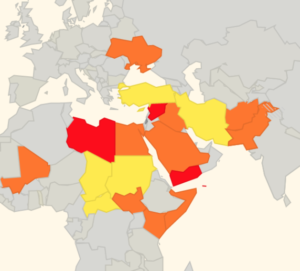

What are surface-to-air missiles, and who has them?

What are surface-to-air missiles, and who has them? There is some evidence to suggest that more States are starting to provide better guidance and information to assist operators in making appropriate routing decisions, but we think this still has some way to go.

There is some evidence to suggest that more States are starting to provide better guidance and information to assist operators in making appropriate routing decisions, but we think this still has some way to go.

In Short: Following a three-year effort from industry groups and aircraft manufacturers, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) will raise the weight threshold for requiring hardened cockpit doors for aircraft with 19 or fewer passenger seats from 45.5 metric tons (100,310 pounds) maximum certificated takeoff weight to 54.5 metric tons (120,152 pounds).

In Short: Following a three-year effort from industry groups and aircraft manufacturers, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) will raise the weight threshold for requiring hardened cockpit doors for aircraft with 19 or fewer passenger seats from 45.5 metric tons (100,310 pounds) maximum certificated takeoff weight to 54.5 metric tons (120,152 pounds). The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has changed its weight rules regarding strengthened cockpit doors on business jets. Toughened doors are required for aircraft operating charter flights.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has changed its weight rules regarding strengthened cockpit doors on business jets. Toughened doors are required for aircraft operating charter flights.