China held new drills near Taiwan on Monday, a sign that they may intend to normalize their military presence around Taiwan. This came a day after the Chinese military ended their extensive 3-day exercises encircling Taiwan, effectively simulating a blockade.

During those exercises, there were significant impacts to flight ops in the region. Xiamen Airlines and Korean Airlines made adjustments to several flights to avoid the airspace, Cathay Pacific pilots were reportedly advised to carry an extra 30 minutes of fuel, and there were cancellations at RCTP/Taipei airport in Taiwan and ZSAM/Xiamen and ZSFZ/Fuzhou airports in mainland China.

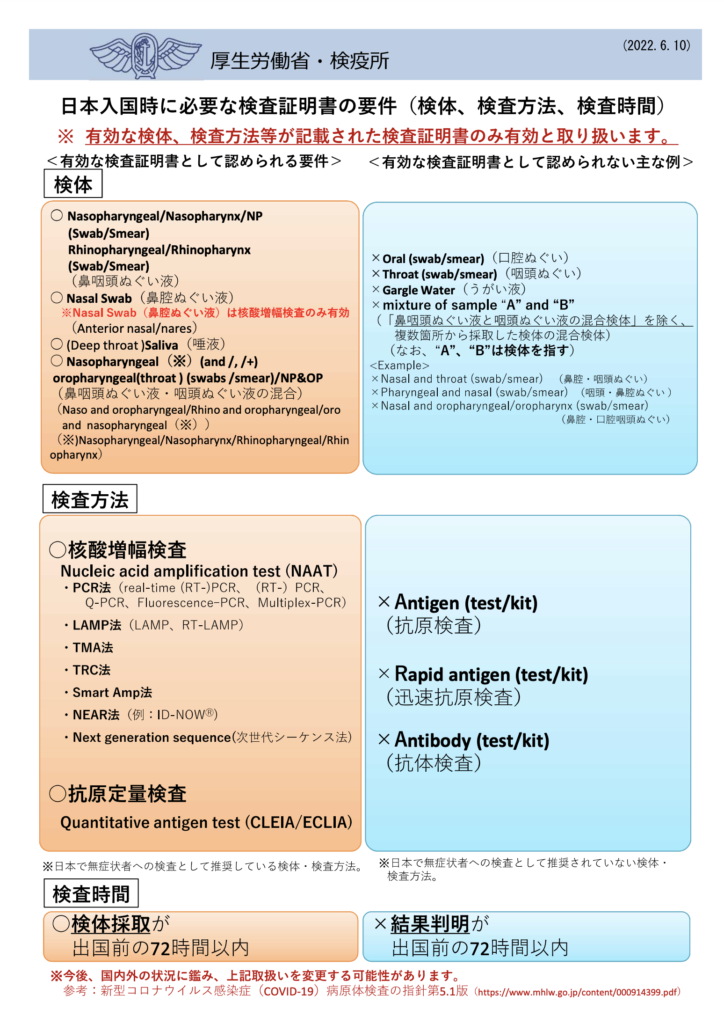

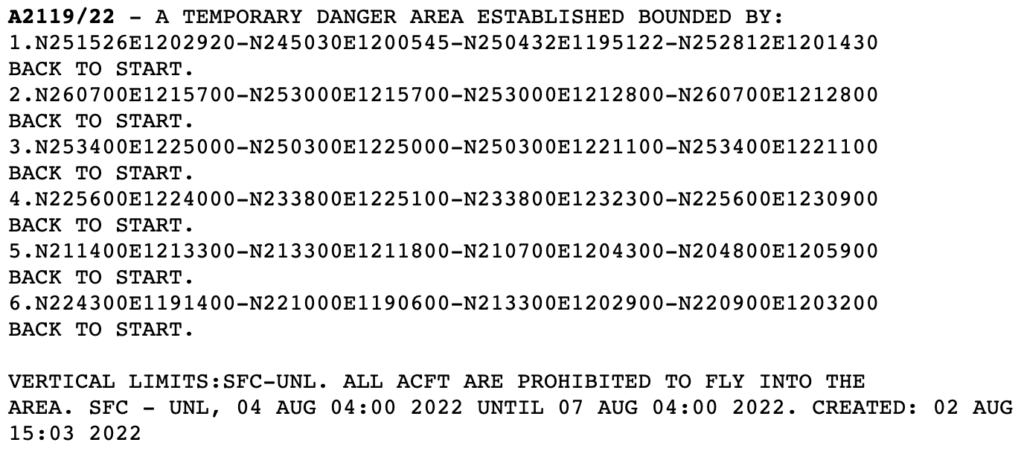

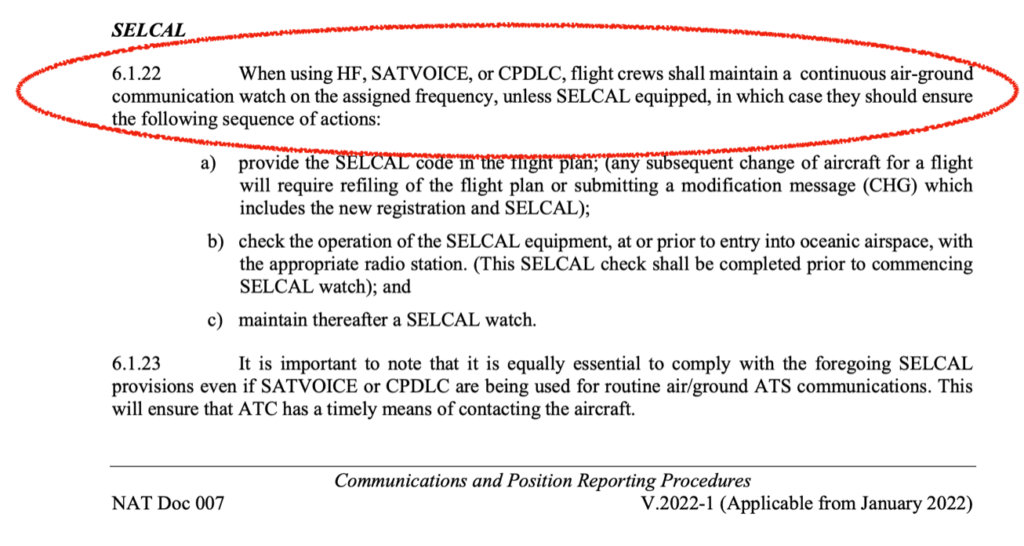

China published ZBBB Notam A2119/22 which set out the six Danger Areas where flights were prohibited at all levels:

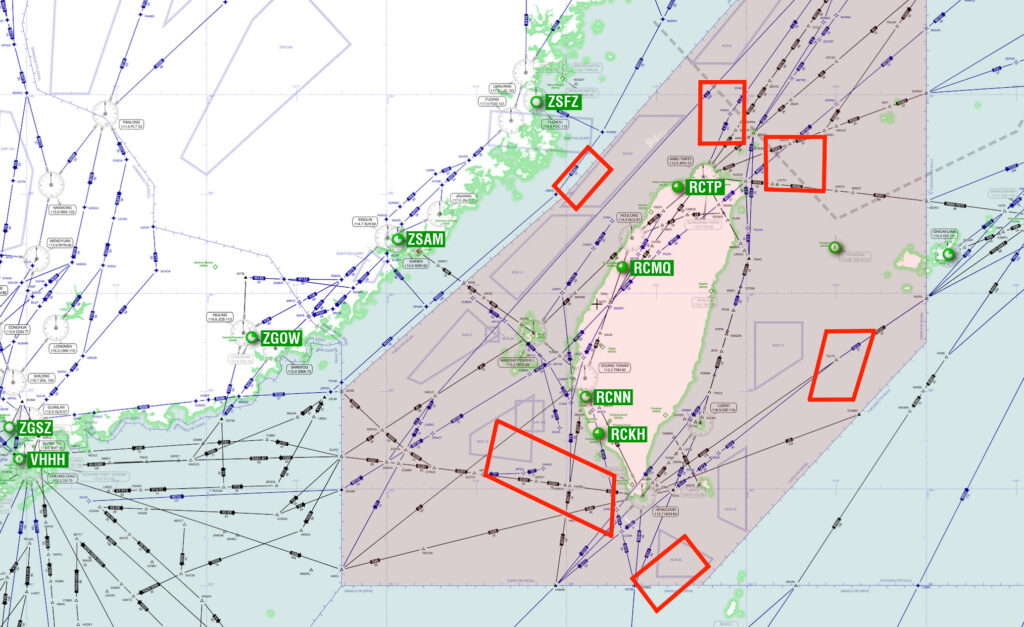

Here they all are, plotted on a map:

Red squares = Danger Areas. Green = Airports. Shaded red area = RCAA/Taipei FIR.

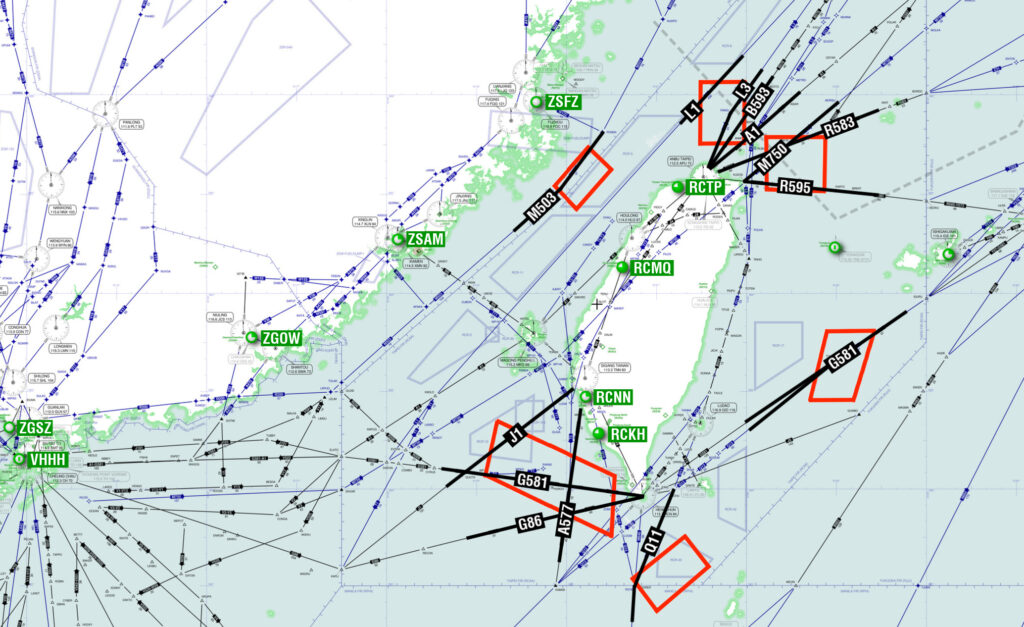

And here are all the main airways that intersect those Danger Areas:

The Danger Areas affected major routes between Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia.

For any future exercises that China announces, if you’re planning on transiting the RCAA/Taipei, ZSHA/Shanghai or RPHI/Manila FIRs then make sure you check the ZBBB Notams as it might not show up as part of your flight briefing pack.

Hypersonic missile launch

China launched an unannounced hypersonic missile on Aug 1 (we could not find any Notams for it). This marked the 95th anniversary of the Peoples Liberation Army being founded, and coincided with an announcement from the US that they might visit Taiwan.

The missile was only fired towards Taiwan, falling some 120km off the coast into the Taiwan Strait.

Taiwan-China procedures

Specific procedures regarding international flights into Taiwan have existed for years, and you can find more in-depth information on these here, and a post on general tips for China Ops here.

A brief summary:

- Foreign registered aircraft are prohibited from operating directly between China and Taiwan.

- If you need to make a tech stop between the two, VHHH/Hong Kong or VMMC/Macau are good options.

- The same rules apply for China overflights – if you’re flying to Taiwan from any third country, you can’t overfly China.

- Only Chinese and Taiwanese registered aircraft are able to operate directly between China and Taiwan.

Because of these, the airspace over the Taiwan Strait is not hugely busy and the missile posed a limited risk to aircraft.

Heightened military activity

China have been showing heightened military activity in and around the South China Sea, ownership of which is disputed by neighbouring countries. This is not directly linked with the Taiwan situation, but provides some further political (and flight ops) awareness, particularly because of the strategic military positions China hold in this region.

In addition, China have been carrying out military drills in various areas, mainly near the East China and Bohai seas. These rarely impact flight operations, with the prohibited zones focused on maritime traffic. However, increased offshore helicopter traffic and some flight disruptions into coastal airports do occur.

China have been increasing their incursions into Taiwanese airspace for a while, with a spate of them towards the end of 2021. These pose some risk to commercial operations for several reasons – increased military traffic being the obvious one. A lesser risk of misidentification is heightened as well, along with the potential response if a civilian aircraft accidentally encroaches on out of bounds Chinese military airspace (well, all of it is military, but some of the really ‘don’t go in there’ parts).

What if China shut their airspace?

We are not saying it will.

However, China are initiating a major offensive in Taiwan, and this does draw parallels to Ukraine and Russia. If the US military becomes involved, this may lead to sanctions between the two countries. Some early consideration as to what airspace closures might mean is therefore a good idea.

China is a major air corridor, particularly with Russian airspace currently closed to the US and Europe. Reduced access or closure of the airspace will see flights routing far further south via Japan, and potentially across the South China Sea before routing across Thailand, India and Pakistan and the Middle East.

The impacts would be significant for various reasons:

- This will significantly increase flight times and distances, and likely be prohibitive for aircraft with lesser range capability (without fuel stops).

- The South China Sea may see increased risk levels if China increase their military presence there as well.

- Summer weather patterns can create further routing difficulties particularly around the Bay of Bengal area.

Other threats to consider.

The Cyber Threat

Chinese action in terms of cyber security breaches have been questioned more than once.

The political stuff

China and the US have a history of ‘messy’ visas for aircrew already. Further tensions are likely to increase this. Security for certain nationalities will need consideration.

Trade

China is a major trade partner with the US and Europe and sanctions on trade may impact aircraft parts manufacture.

Trickle effect at airports.

Trickle effect at airports.

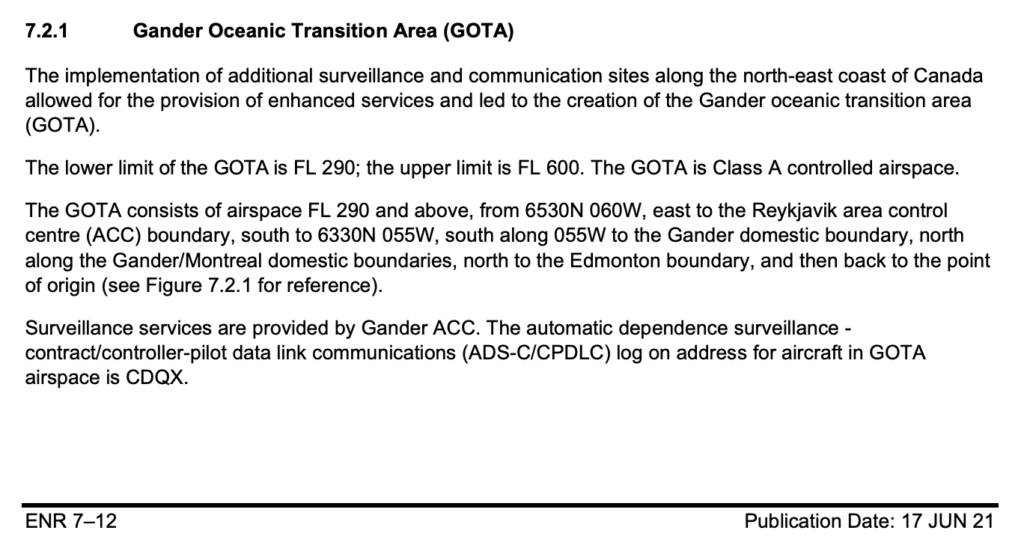

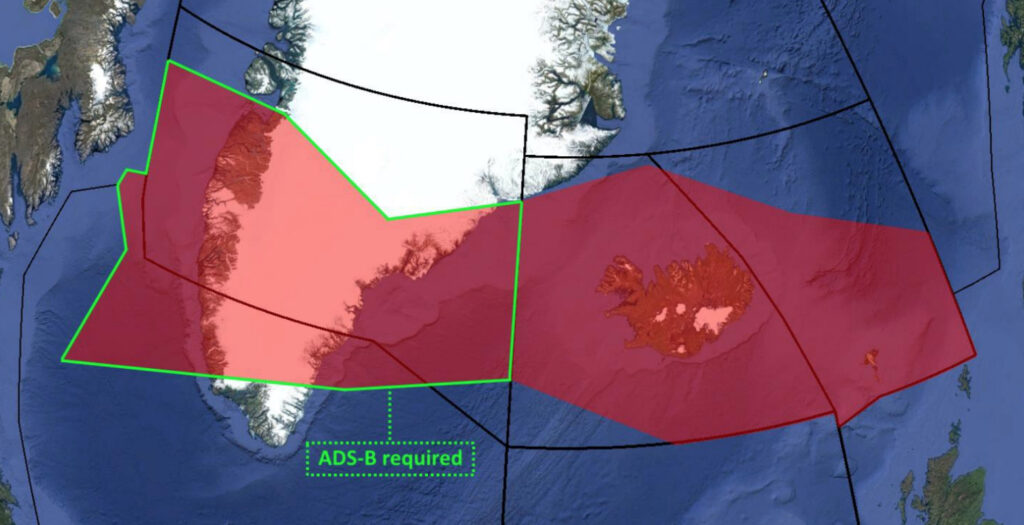

This the datalink exempt ATS Surveillance airspace over Greenland, Iceland, and a bit of Gander Oceanic where you can still fly if you don’t have datalink.

This the datalink exempt ATS Surveillance airspace over Greenland, Iceland, and a bit of Gander Oceanic where you can still fly if you don’t have datalink.

But there’s a problem on the NAT…

But there’s a problem on the NAT… Nav Canada has confirmed to us that this will indeed will be the case. An AIC will soon be published, which is due out in September.

Nav Canada has confirmed to us that this will indeed will be the case. An AIC will soon be published, which is due out in September.

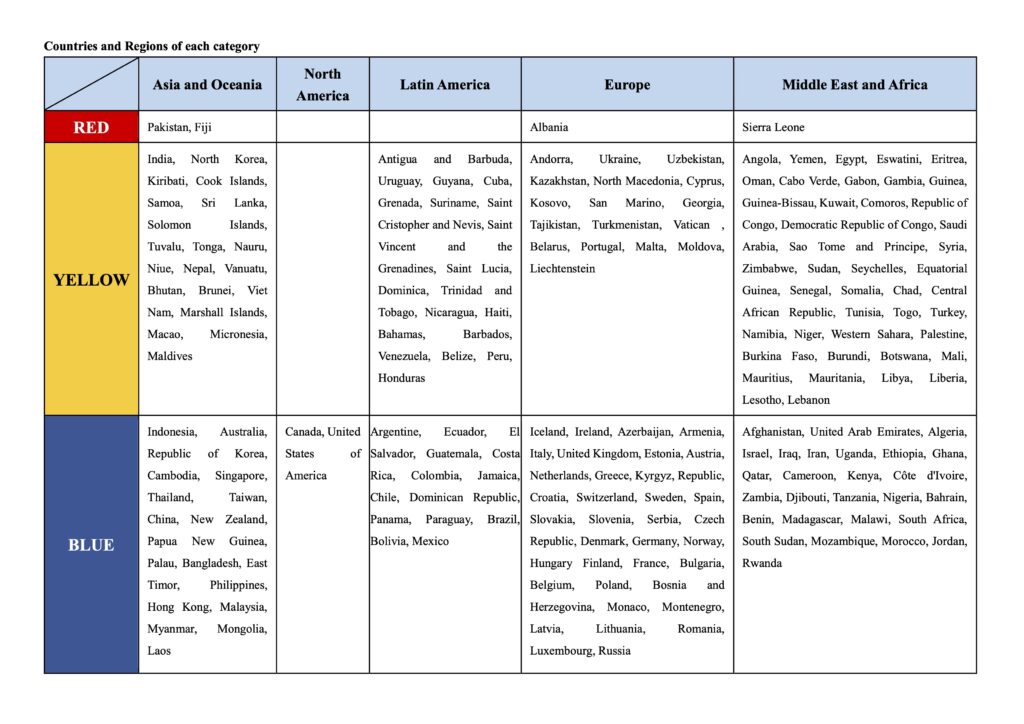

The rules you need to follow depend on where you have been in the past fourteen days – the most restrictive country applies.

The rules you need to follow depend on where you have been in the past fourteen days – the most restrictive country applies.