Are you Trevelyan across the NAT HLA anytime soon? Then here is a summary of the changes that just came out in NAT Doc 006.

What is Doc 006?

It is the Air Traffic Management Operational Contingency Plan for the North Atlantic Region, and we are talking about the Second Edition, August 2022 version which you can find here if you want a look. The last time it was updated was back in Feb 2021, and we covered those changes here.

Page 1

“Aha, a handy list of all the changes,” think Rebecca and Dave as they glance at page one. “This will be easy. Our job is done already.”

“What does it say?” Rebecca asks.

“It says that there is a new chapter on Common Procedures which were there but are now here…” replies Dave. “And also something about a Notam and some route something somethings…”

“There’s still a lot of red again, isn’t there?” whispers Rebecca.

“Yes, there is,” sighs Dave.

“Should we read it for them?” Rebecca says wearily.

Dave nods.

All the changes are in red.

Finding the changes isn’t hard. Understanding them is the annoying bit. So we shall try and make sense of what all those changes are for you so you don’t have to.

(But before we go on though, here is the record of amendments so you can see if any of it looks remotely interesting to you. If not then you can go and do something much more interesting with your time instead of reading further.)

The Changes.

Chapter 1

They have updated the information on contingency situations thats might affect multiple FIRs. What could cause that? Volcanic ash could cause that.

They have also added in Reykjavik.

Chapter 1

Sorry, that bit before was just an intro or something.

So, Chapter 1 – Common Procedures.

- Limited Service: If ANSPs are going to only be able to provide a limited service they will try and let everyone know at least 12 hours in advance by Notam. This is for times like if datalink going to be down or if there are some huge solar flares heading their way that might take out their HF for a bit.

- No Service: It’s the No Service Situations we really need to worry about. If this happens then they will get a message to whoever they can, and whoever gets the message will help share it out to as many people as they can.

In any region, the results will be the same. With Comms disruption, they will obviously attempt other methods. There is likely to be a fair amount of frequency congestion on whatever methods are still working.

With control services, there may be some additional restrictions which affect traffic flows, and there may well be reroutings. Where possible, these will be limited to those not yet in the NAT (a bit easier for the old fuel planning).

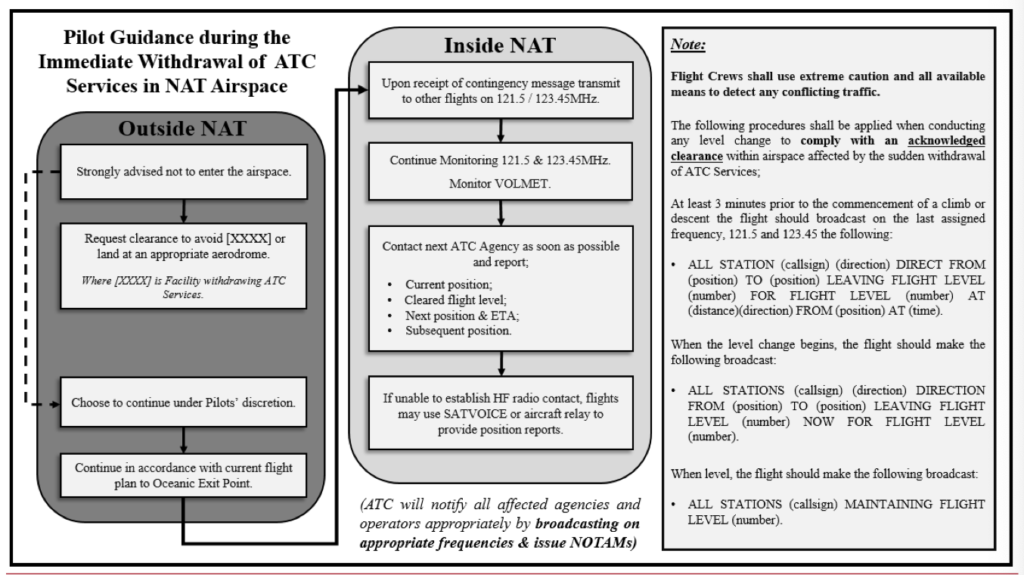

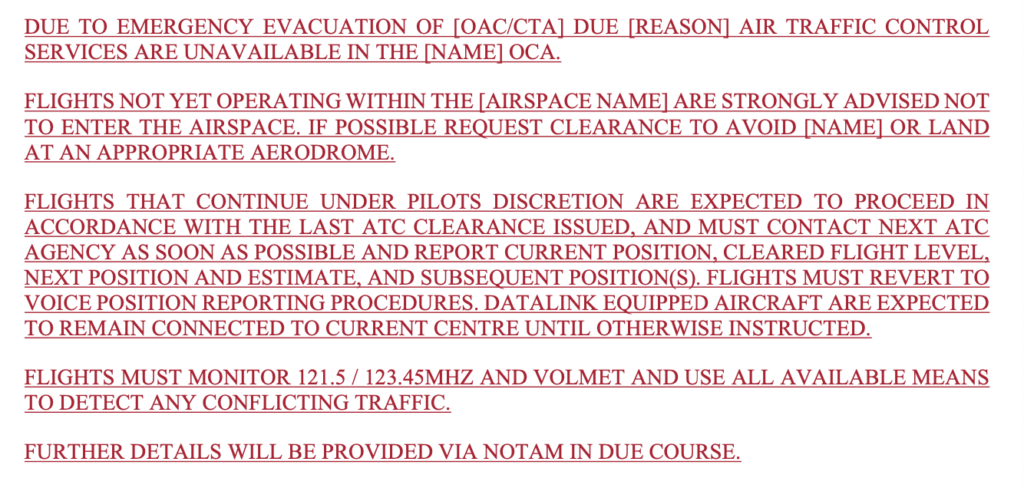

In the event of a sudden withdrawal of services, here is an excellent chart for pilots to print out and have handy.

Strongly advised…

Immediate withdrawal of services

It’s what the handy guide says, but in case you don’t want to read that:

- Already in the NAT? Basically, stick with the last received and acknowledge clearance, try and talk to anyone you can and make sure you give position reports. You can use SATVOICE for this too. If you’re in the middle of a level change, complete it as quickly as you can. If it’s a control centre evacuation and you’re on ADS then revert to voice.

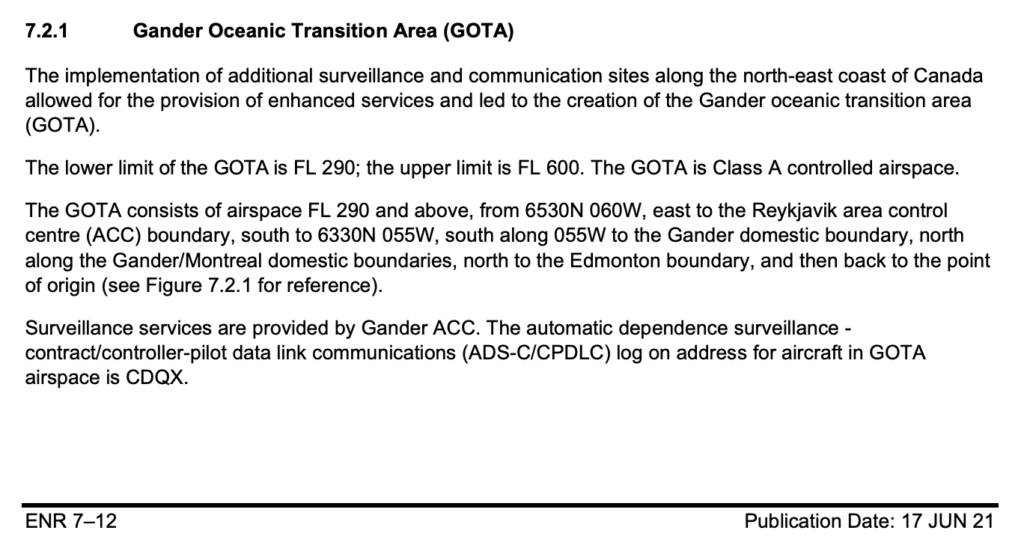

- Approaching the NAT? If you’re within 20 minutes and it is getting evacuated then stick with your last clearance. Only aircraft less than 60 minutes from their OEP can transit Gander. They guarantee no conflict profiles.

The Next Chapters

Shanwick: Contingency procedures have moved to chapter 11.

Gander: Nil Red

Reykjavik: This has a lot of new info, although not specifically in this section. The main thing is, if you can’t get hold of Iceland Radio HF then try Shanwick radio first, then Gander or Bodø if still no luck. Reykjavik is the only FIR without supporting procedures.

Santa Maria: If Comms are down and you have ATS safety SATVOICE (INMARSAT or IRIDIUM) then you can call them on 426302 or 426305. If you have a non ATS safety satellite network (some big old sat phone from the 80’s onboard) then try +351 296 886 655 but only if you really, really need to.

New York: Nein Rot.

Bodø: Bodø ACC includes Domestic control, Oceanic and Radio (HF). Thankfully it can be supported by basically all its neighbours FIRs (except Reykjvik).

Shannon: Non Rouge.

Brest: No roja.

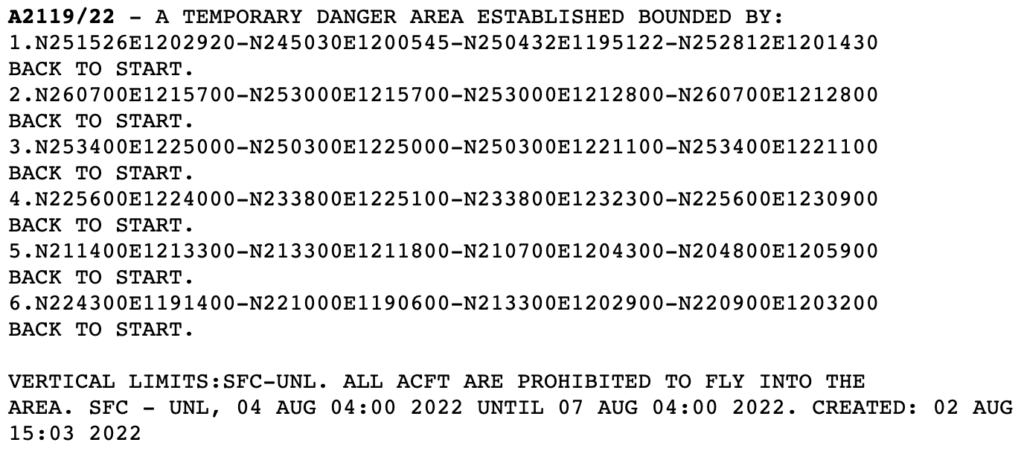

Chapter 10 – Notification Messages

Or ‘The Great River of Red’ as I know call it. Actually, most of this can be looked at in the below image (it’s a picture of their example of a Notam).

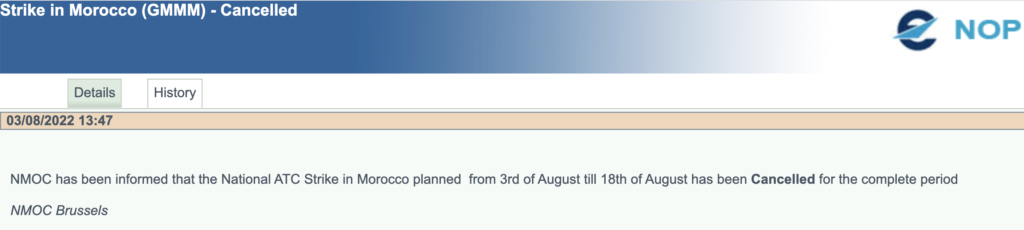

Limited service? Info will be sent via other ANSPs.

No service? It has probably been evacuated and notifications of this will be sent via the NAT track messages and transmitted on any appropriate frequencies.

The example Notam. Although it probably won’t actually be red if you see it for real.

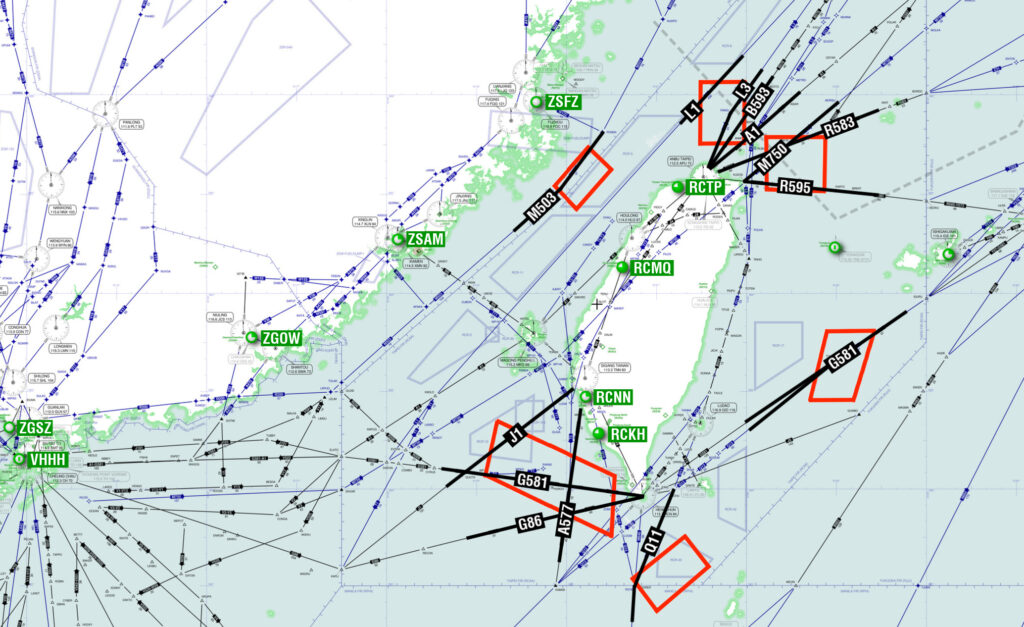

Chapter 11 – Route Structures

This contains info on the routes for each region. Mainly Reykjavik because they’ve added all of those in. There are some nice diagrams in this bit.

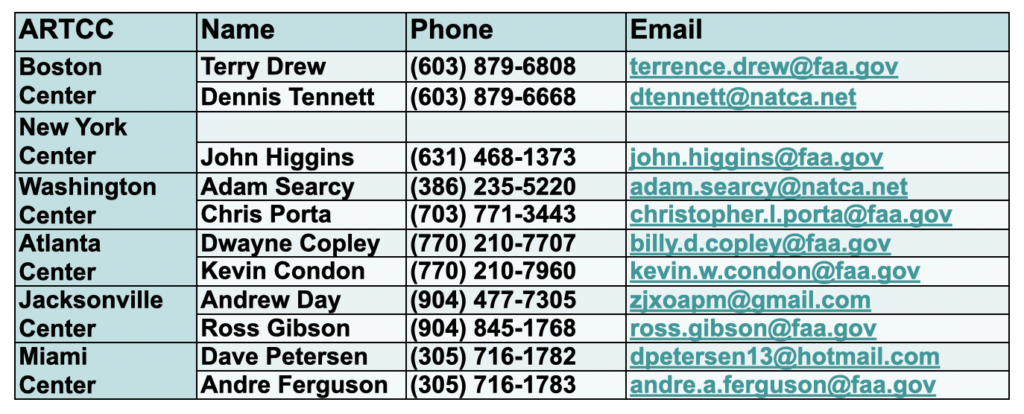

Chapter 12 – Contact Info

This is the contact details. Lots of red for the new Reykjavik folk.

That’s it. We’re off to play some Goldeneye on our N64. Found something important that we missed? Let us know! news@ops.group

Trickle effect at airports.

Trickle effect at airports.

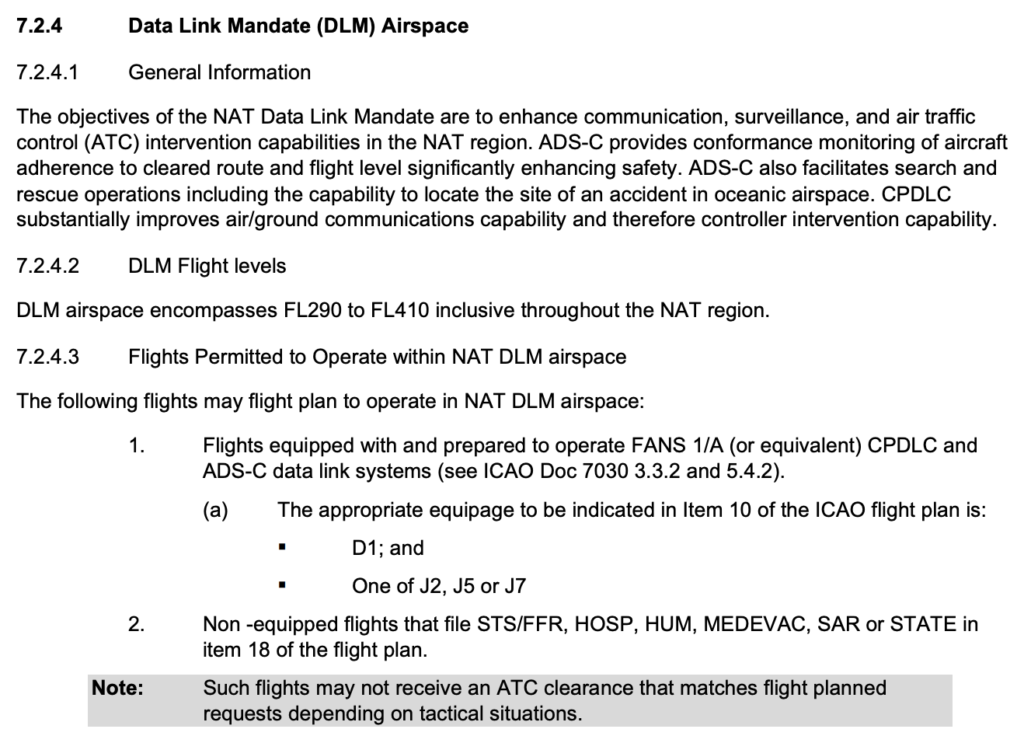

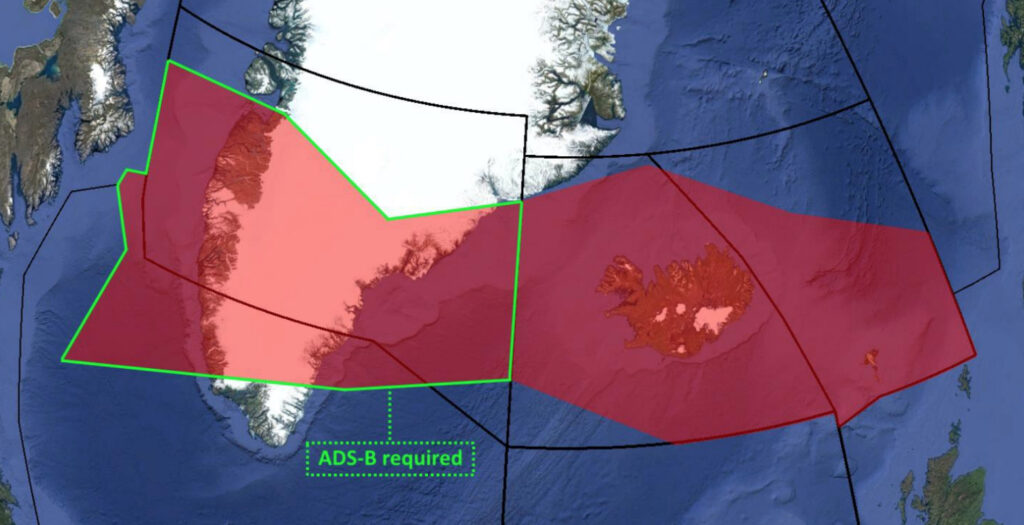

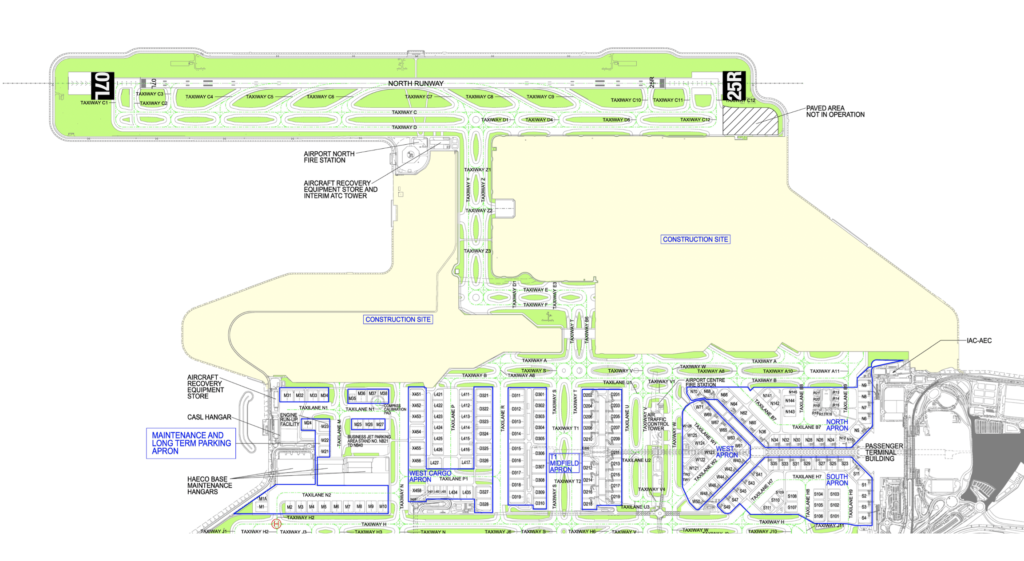

This the datalink exempt ATS Surveillance airspace over Greenland, Iceland, and a bit of Gander Oceanic where you can still fly if you don’t have datalink.

This the datalink exempt ATS Surveillance airspace over Greenland, Iceland, and a bit of Gander Oceanic where you can still fly if you don’t have datalink.

But there’s a problem on the NAT…

But there’s a problem on the NAT… Nav Canada has confirmed to us that this will indeed will be the case. An AIC will soon be published, which is due out in September.

Nav Canada has confirmed to us that this will indeed will be the case. An AIC will soon be published, which is due out in September.

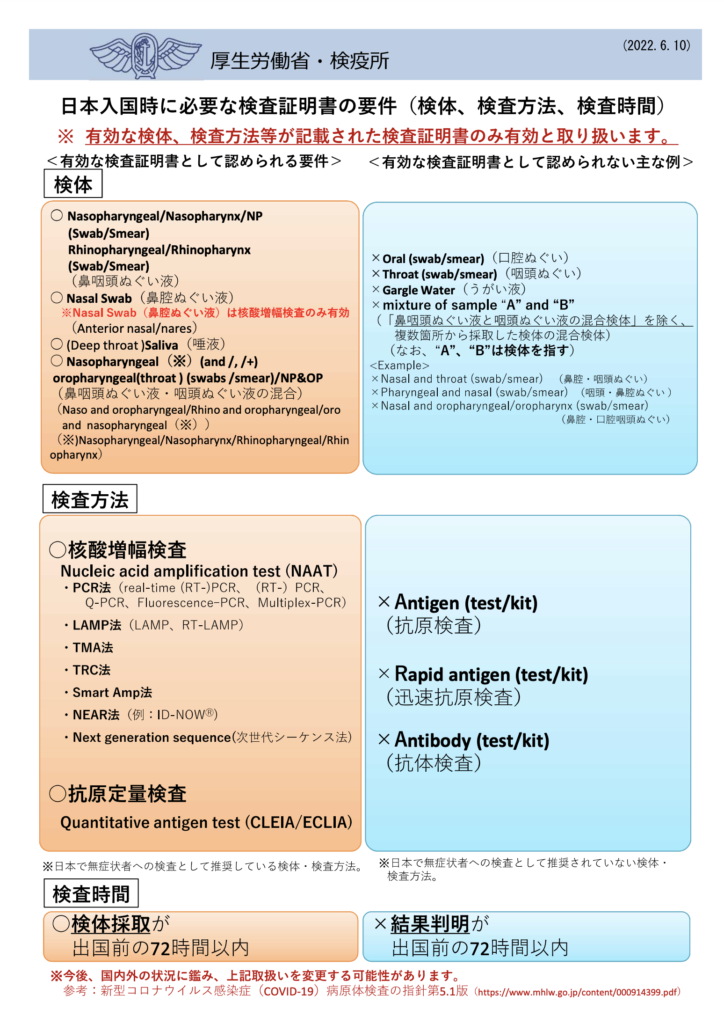

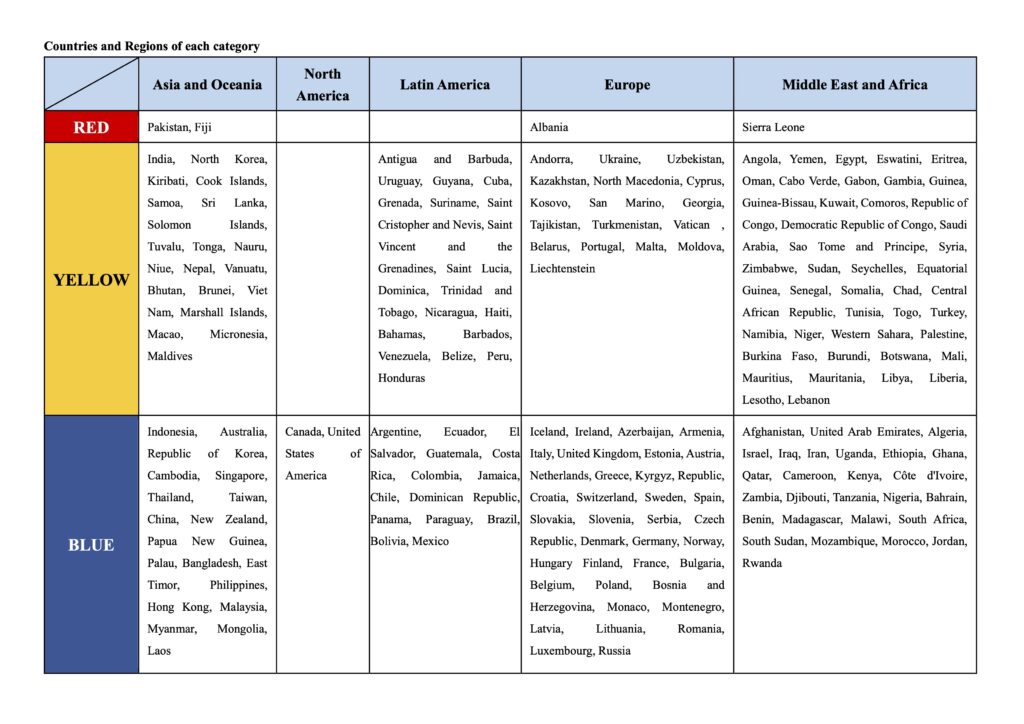

The rules you need to follow depend on where you have been in the past fourteen days – the most restrictive country applies.

The rules you need to follow depend on where you have been in the past fourteen days – the most restrictive country applies.