Since January this year, any passenger boarding an international flight bound for the US must have a Covid test within 3 days of their departure.

Great when it’s negative. Not so much if its positive – what happens then? How do you carry them back to the US? And what about their close contacts? Are they good to go?

Let’s take a closer look…

The US law says you cannot knowingly carry someone with known or suspected Covid-19 to or within the US on regular passenger flights. You can’t even board them.

Instead, as a general rule they won’t be able to travel until they meet CDC quarantine or isolation guidelines (typically staying put for ten days and more testing), in addition to whatever local laws apply. A great reason to have travel insurance.

But what if they have to travel?

There are important reasons why a Covid-positive passenger might have to fly. The most common one is that they are being medically evacuated or transferred to better medical facilities. It may also be part of the passenger’s insurance policy.

Either way, it falls upon charter or medevac operators to make it happen because the rules say that this is the only way. The airlines just can’t be used.

Forget ‘the brush.’

If you’re chartered to carry Covid positive passengers – or those suspected of having it – you need to be familiar with the CDC’s procedure for transport by air. Spoiler alert: you need permission, so whatever you do don’t show up unannounced.

You can read that procedure here in all its glory. But here’s a quick rundown of how it works.

It starts with the phone.

If you’re operating an international flight, the first step is to contact the relevant US Embassy. There may be local laws or restrictions that prevent a Covid positive patient from being allowed out of quarantine early.

Then, over in the US, there are three important agencies that you’ll need approval from:

- The FAA – yep, make sure they’re cool with it.

- Customs and Border Protection – they will work with you to decide on the best port-of-entry.

- The CDC – This involves contacting the relevant quarantine station for where you’re headed – and you’ll need to give them at least 24 hours’ notice before you take-off. There’s a bunch of info they’ll need – click here for that list.

You’ll also need to think about the logistics of your flight including transport, permission from other CAAs and airport authorities – including where you may need to divert to.

Pre-travel.

Prior to the big day it goes without saying that your unwell passenger(s) should stay in isolation. They’ll need a medical exam beforehand to make sure they are well enough for the level of care you can provide them in the air.

You’ll also need to work with airport authorities for a plan. If you have to enter a terminal, your passengers will need to be separated from the public.

Choose your ride.

When it comes to transporting unwell passengers, not all airplanes are created equally.

The CDC has guidelines for this too. They were developed back when MERS was thing. Remember MERS? It was like Covid’s lesser known cousin that appeared a few years back but was way less memorable at the party.

In a nutshell they need to be large enough to be able to separate passengers and crew into different parts of the airplane. Ventilation is also important – ideally, cockpit air should have positive pressure relative to the main cabin and not be mixed.

Don’t forget to think about range. Every stop you make will become a logistical challenge to manage. If you can make it in one go, you should.

On-board.

First things first, keep that air flowin’. At all times. Even on the ground during long delays, you need to keep ventilating the airplane.

Passengers and crew must wear masks – don’t worry you can remove them to sip on your coffee. You can get away with basic ones, but the CDC recommends the fancier N95 masks or better.

Here’s the kicker – crew need to remain separated from passengers unless there is an emergency or to provide single-serve meals. You can put up placards or barriers but they need to be obvious and not stop anyone from reaching emergency exits or seeing cabin signs.

If you can, seat passengers at the rear of the aircraft and keep cabin crew at the front – at least six feet away. The reasons for six feet will become clear in a sec. Pax should have their own bathrooms.

After landing.

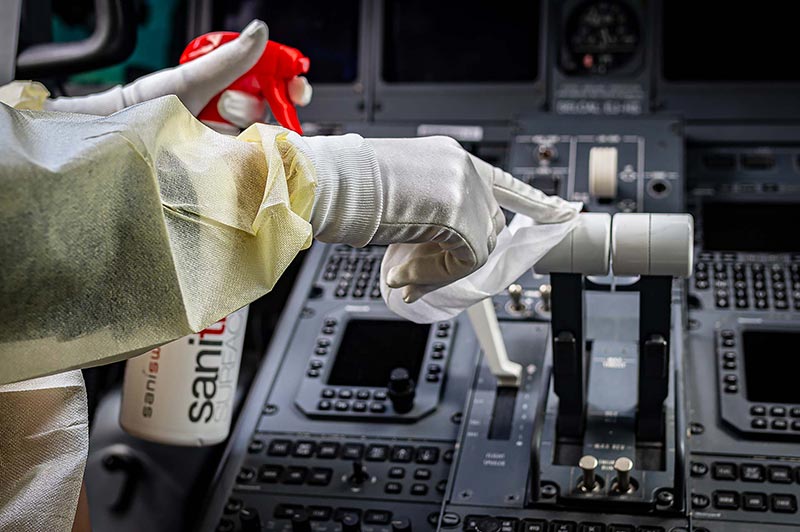

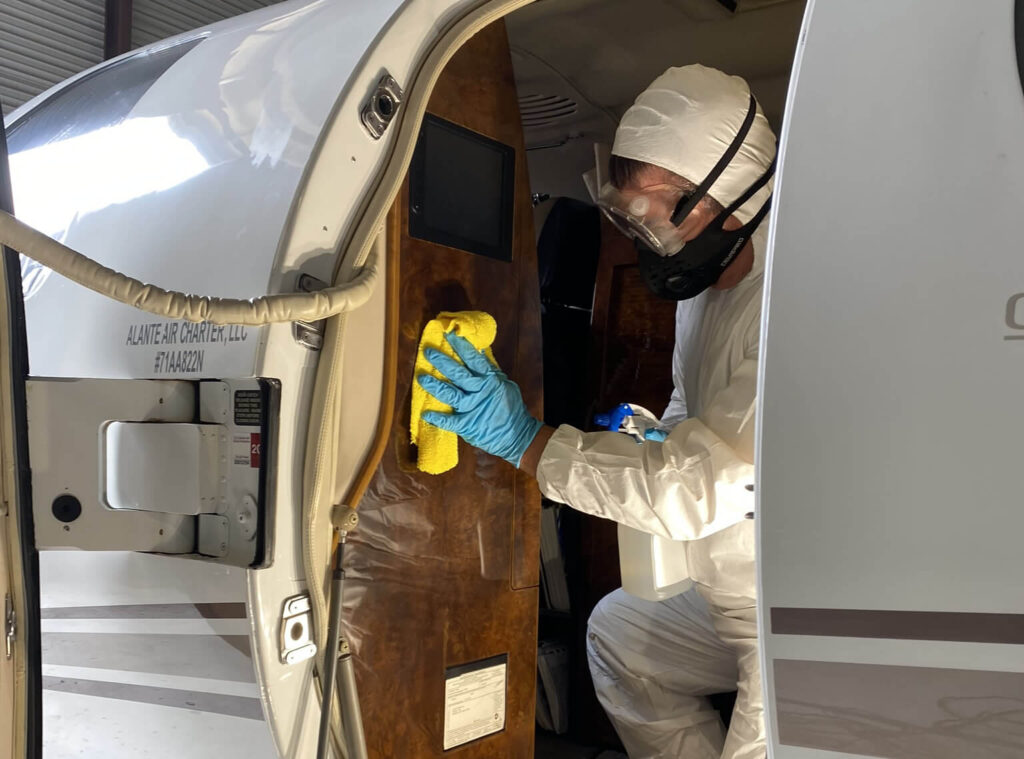

The airplane will need to be thoroughly cleaned. As in squeaky clean. There are rules for what types of products need to be used – you can read about that here.

Post-flight cleaning needs to be squeaky clean.

As for crew, as long as you’ve followed the rules, you don’t need to be tested or quarantine. But make sure you self-monitor for symptoms for 14 days afterwards, just in case.

The ‘close contact’ conundrum.

This is where things start to get tricky…

Being a ‘close contact’ of a known Covid case for all intents and purposes means you have been exposed.

But what counts as ‘close’? Brace yourself, because the CDC have that base covered – it means anyone who has been within six feet of a confirmed case for a cumulative total of 15 minutes over 24 hours. Cumulative being important here – so for example, three 5 minute exposures counts as ‘close’. It doesn’t need to be all in one hit.

So, what happens when a known close contact still tests negative?

There’s effectively three scenarios here:

- The close contact is fully vaccinated and has no symptoms: Okay, they can still travel.

- The close contact is fully vaccinated but has symptoms: No bueno, it’s off to quarantine.

- The close contact hasn’t been vaccinated: No bueno, it’s off to quarantine.

Cool, so can Covid positive passengers be transported with their close contacts?

No. But you can transport multiple positive pax together, you just can’t mix positive ones with those who have tested negative.

Still have questions? We don’t blame you. Here are some handy places to start.

The CDC website, you can visit it here.

The US FAA, their Covid specific stuff is found here.

If you’re trying to reach Customs and Border Protection, you can reach em’ here.

A is for Airplane, flying high as a bird

A is for Airplane, flying high as a bird B is for Bureaucracy and unreadable words

B is for Bureaucracy and unreadable words C is for Covid not going away

C is for Covid not going away D is for Datalink on the NAT HLA

D is for Datalink on the NAT HLA E is for Errors of the Gross Nav variety

E is for Errors of the Gross Nav variety F is for OpsFox, a secret society

F is for OpsFox, a secret society G is for Guy Gribble, gone too soon

G is for Guy Gribble, gone too soon H is for Humans, me and you

H is for Humans, me and you I is for Israel overflight clearance

I is for Israel overflight clearance J is for Jamming and GPS interference

J is for Jamming and GPS interference K is for Kiwis showing us what to do

K is for Kiwis showing us what to do L is for Lockdown, no kiwi for you

L is for Lockdown, no kiwi for you M is for Members, colleagues and friends

M is for Members, colleagues and friends N is the Notam problem again

N is the Notam problem again O is for OPSGROUP, share what you know

O is for OPSGROUP, share what you know P is for Pilots flying us home

P is for Pilots flying us home Q is for Quarantine in a government compound

Q is for Quarantine in a government compound R is for Relief Air Wing, eyes on the ground

R is for Relief Air Wing, eyes on the ground S is for SafeAirspace, where not to fly

S is for SafeAirspace, where not to fly T is for Towers, controlling the skies

T is for Towers, controlling the skies U is for Unreliable speeds on aircraft stored too long

U is for Unreliable speeds on aircraft stored too long V is for going Viral when you do something wrong

V is for going Viral when you do something wrong W is for Winter Ops, cold weather tips

W is for Winter Ops, cold weather tips X is for Space X, launching their ships

X is for Space X, launching their ships Y is for a big Yes to 2021

Y is for a big Yes to 2021 Z is for Zoom calls – sometimes they’re fun!

Z is for Zoom calls – sometimes they’re fun!

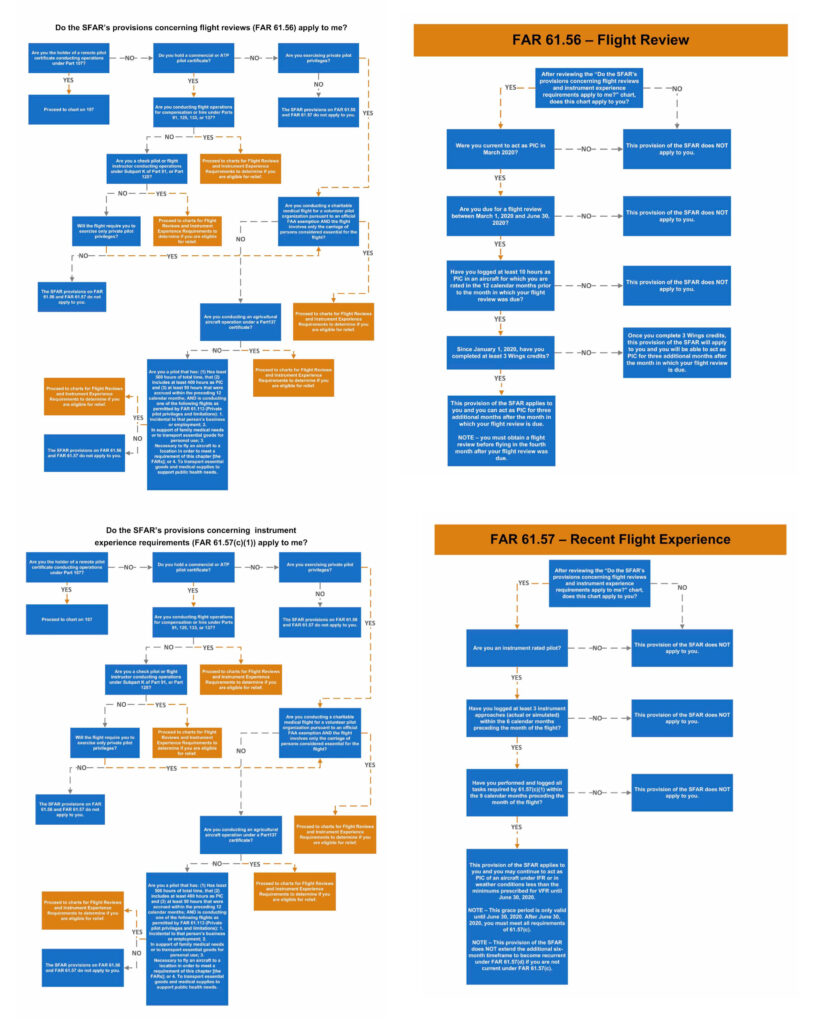

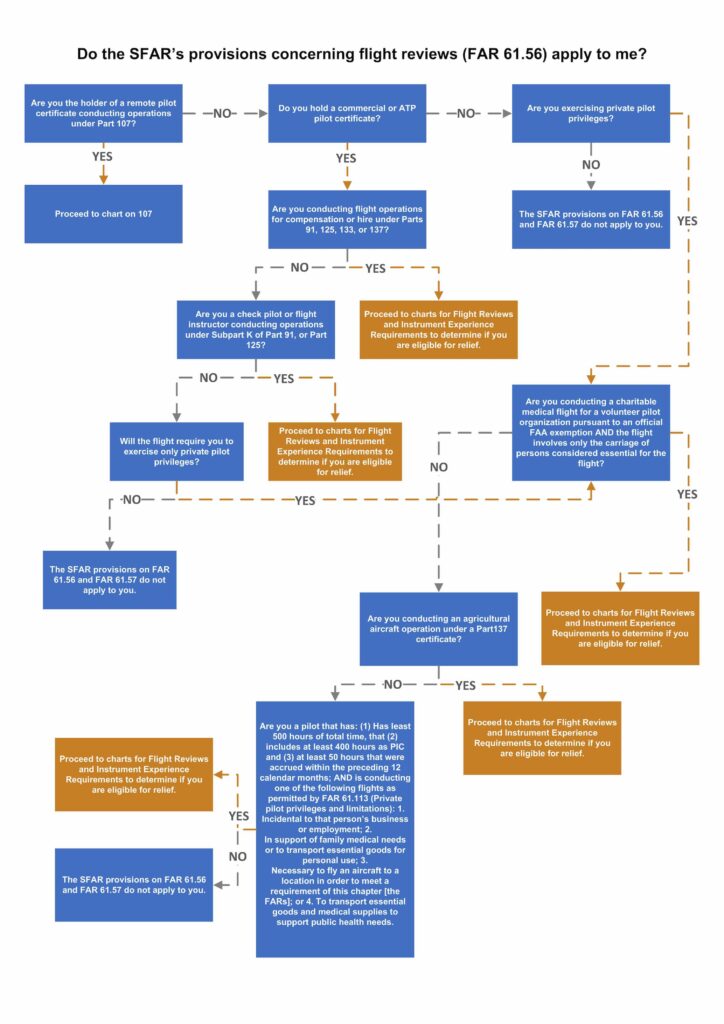

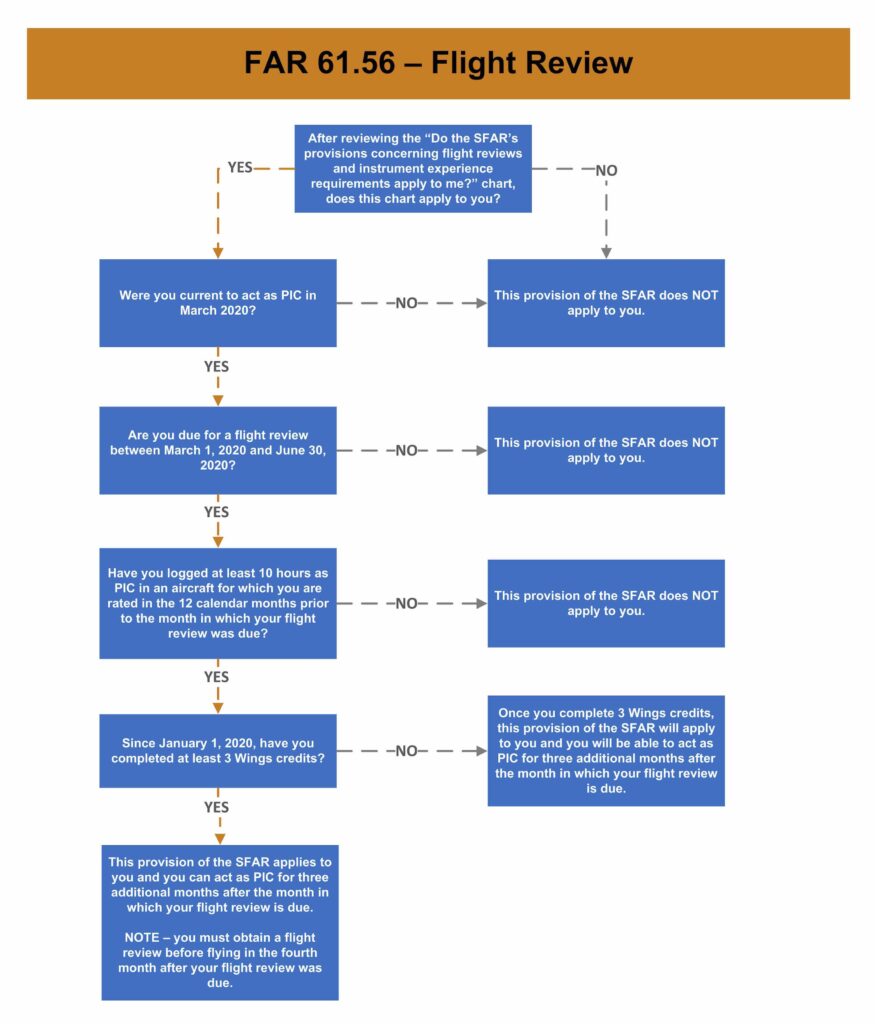

The first question to ask yourself is, “Were you current to act as pilot in command in March 2020?” If the answer is yes, the next step is to check your flight review expiration date. If the expiration date falls between March 2020 and June 2020, next determine whether you have flown 10 hours as PIC in an aircraft for which you are rated in the 12 calendar months prior to the month when your flight review was due. (Again, a “no” answer means you would continue with your usual flight review schedule.)

The first question to ask yourself is, “Were you current to act as pilot in command in March 2020?” If the answer is yes, the next step is to check your flight review expiration date. If the expiration date falls between March 2020 and June 2020, next determine whether you have flown 10 hours as PIC in an aircraft for which you are rated in the 12 calendar months prior to the month when your flight review was due. (Again, a “no” answer means you would continue with your usual flight review schedule.)

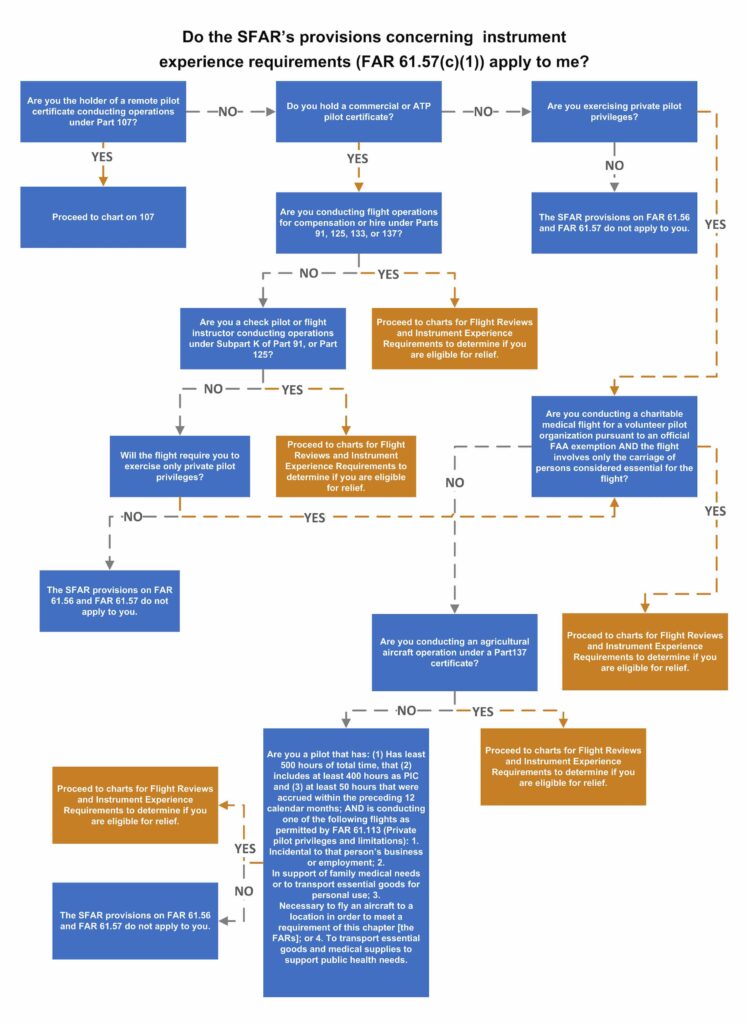

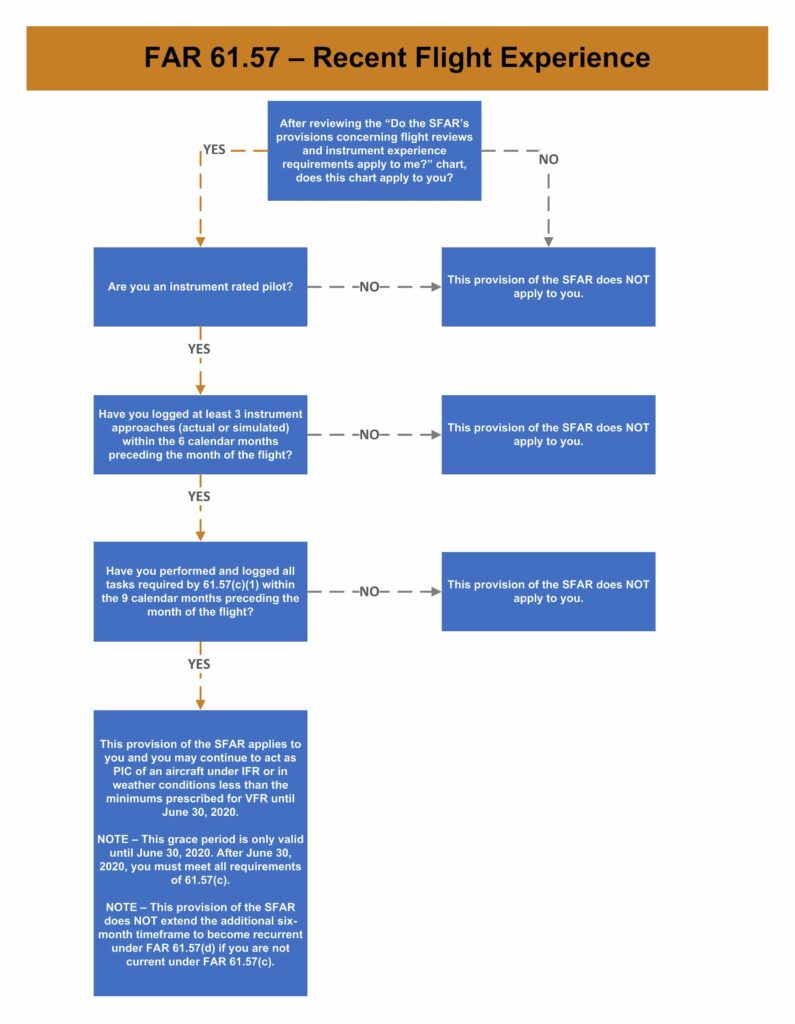

Instrument pilots who plan to exercise their privileges to conduct “specific operations for which the FAA has determined relief is appropriate” under the SFAR must also verify their recency of experience. Again, the steps can be tracked on the flow chart, and if at any time you find yourself in the “no” column, it means you must get an instrument proficiency check as would usually be the case at this point in your recency-of-experience cycle.

Instrument pilots who plan to exercise their privileges to conduct “specific operations for which the FAA has determined relief is appropriate” under the SFAR must also verify their recency of experience. Again, the steps can be tracked on the flow chart, and if at any time you find yourself in the “no” column, it means you must get an instrument proficiency check as would usually be the case at this point in your recency-of-experience cycle.

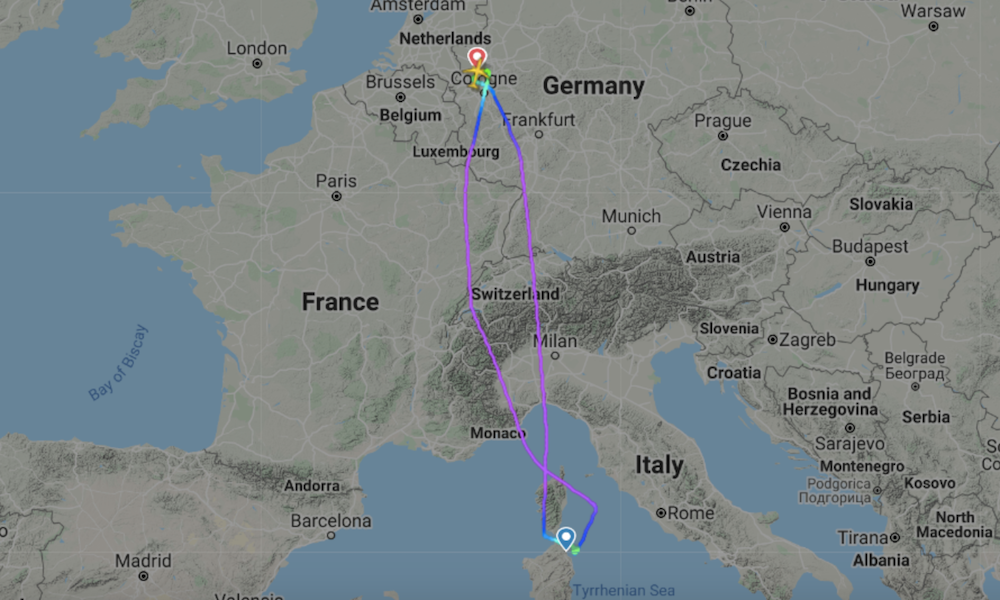

Yes, there was a Notam, and yes, it looks like they missed it – though that’s maybe not surprising given the Notams being pumped out on the national LIBB/LIMM/LIRR codes at the moment saying how pretty much all airports across the country have now reopened – including LIEO!

Yes, there was a Notam, and yes, it looks like they missed it – though that’s maybe not surprising given the Notams being pumped out on the national LIBB/LIMM/LIRR codes at the moment saying how pretty much all airports across the country have now reopened – including LIEO!