Mexico have recently found themselves downgraded by the FAA under their IASA program.

So, what does this mean for Mexico, and what does everyone else need to know about this?

First up, what is the IASA program?

It might sound confusingly like a combination of EASA and IATA, but ‘IASA’ is actually the International Aviation Safety Assessment Program run by the FAA, and used to determine the safety standards in foreign countries.

It was set up in 1992 to monitor air carriers operating in and out of the US – not to monitor the operators specifically, but to check the authority in the country is up to scratch with ensuring their operators are up to scratch. If not, the US don’t want to let them into their airspace.

What do they look at?

They are focusing on the country (not the operators in the country), to see how well they adhere to international aviation safety standards and recommended practices, as suggested by ICAO in Doc 9734.

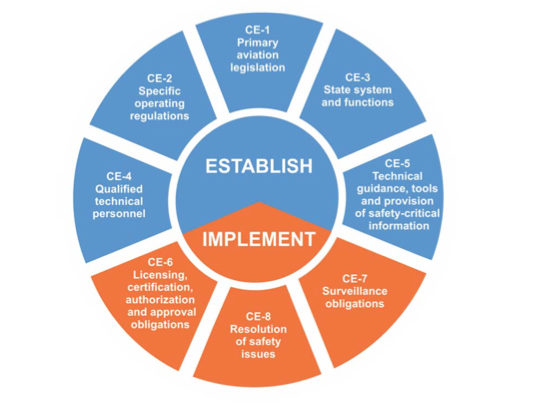

There are 8 elements that the FAA/ICAO reckon a decent aviation safety oversight authority should be doing well:

- Legislation

- Operating Regulations

- The State civil aviation system and safety oversight functions

- Technical personnel qualifications and training

- Technical guidance, tools and provision of safety critical information

- Licensing, certification, authorization and approval obligations

- Surveillance obligations

- Resolution of safety concerns

I feel like they combined a few there, and its actually more than 8. But there’s the list.

The Big 8

How do they do the assessment?

If you visit the IASA site, on the FAA main site, then you’ll find each of those areas has its own checklist. These are thorough, lengthy things. The Operating Regulations alone is 19 pages with a whole bunch of points to check off per page. Oddly, all that checking leads to only two possible outcomes.

A country either meets the standard or it doesn’t. There is Category 1, or there is Category 2, no in-between.

- Category 1, Does Comply with ICAO Standards

- Category 2, Does Not Comply with ICAO Standards

Basically, if one or more deficiencies are identified, it’s a Category 2 ranking, and Santa won’t be bringing you a present that year.

A lot they are looking at

What does it mean to be on the naughty list?

Well, if you already have air carriers flying to the US then you can continue but they are going to monitor them pretty closely. If you don’t already have air carriers operating in and want to, then you’re going to have to improve before they give you permission.

But why should we all care?

After all, the oversight is to do with their air carriers and nothing more? Surely it just means their aircraft might be a risk coming into US airspace, or their pilots might not follow procedures properly?

Well, actually no. The problem is these air carriers share airspace with you. If their pilots are not licensed or trained correctly (think Pakistan’s recent problem) then this can degrade the safety for all aircraft operating in their vicinity.

If a state is failing to ensure minimum safety standards in areas such as the promulgation of safety critical information (notams), technical personnel qualifications (the maintenance folk who might be fixing your aircraft, or the CAA inspectors checking compliance) then this is something any international operators might want to be aware of as well because there are potential knock-on safety impacts for those heading into the country in question.

So does it tell me if another country is safe to fly to?

No. The FAA is not saying every country ranked 1 is safe, no issue, no problem.

It also isn’t telling you a country is unsafe to operate to if they don’t meet compliance standards. Remember, it is purely looking at the regulatory and safety oversight and asking if they ensure minimum ICAO standards. There are countries out there that pose significant threats (just not because of any deficiencies in the authority’s oversight).

It might also mean that the FAA have not ranked that country, because no-one from that country is flying or planning on flying to the US.

Remember, these rankings are looking at how a state ensures its air carriers are safe and compliant. It does not consider whether services or infrastructure within the state itself are safe or compliant.

The DRC isn’t on the list. It’s not the safest place in the world…

How should operators and pilots use this list?

For operators and pilots, if a country is ranked Category 2, it means you might want to be doing your own risk assessment before heading in. No-one is saying that country isn’t going to be safe, but they are saying there are deficiencies with the authority, and since that authority looks after a lot, it is worth asking whether there might be other deficiencies as well.

You should be looking at the following:

- What are the standards of the handling agents and maintenance services you are going to require there?

- How reliable are Notams, and are they providing the information required?

- What level of service and safety will ATC provide?

- Will procedures and regulations be correctly adhered to there, and if not, what will this mean operationally for your flight safety?

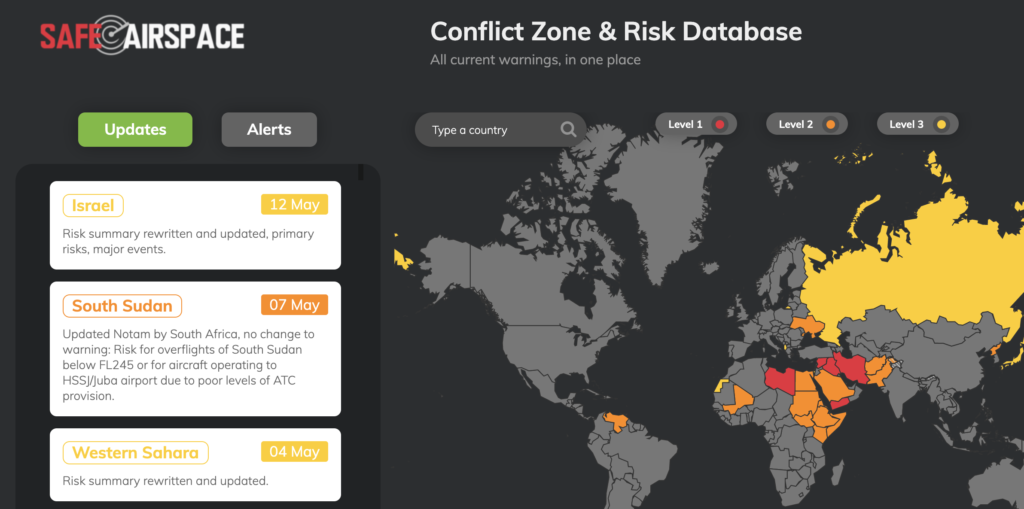

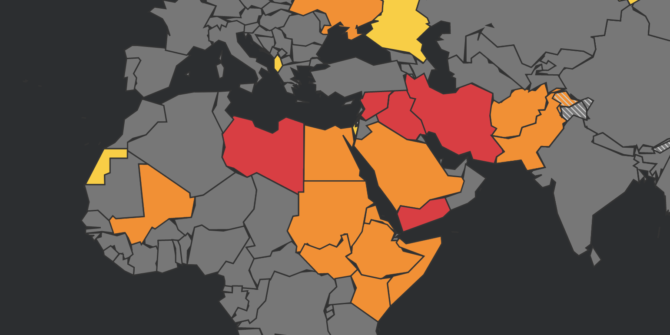

You can get this info from sites like Safeairspace, Airport Spy, and through talking with colleagues who have operated into there before.

Who is on the Category 2 list?

So the big news this week is that Mexico were downgraded. Again, actually.

Along with Mexico the FAA also have the following countries ranked at Category 2:

- Bangladesh

- Curacao

- Ghana

- Malaysia

- Eastern Caribbean States

- Pakistan

- Thailand

- Venezuela

It changes though.

In 2014, the FAA downgraded India, citing inadequate oversight by local regulators, and in 2001 South Korea found themselves downgraded due to unskilled technical staff, pilot screening problems, issues with flight operations rules and a lack of objectivity in air crash investigations.

Both made it back on again relatively quickly.

Let’s take a closer look at Mexico…

The FAA have not yet given the reasons for their downgrade. However, Mexico was downgraded previously – back in 2010 – due to shortcomings in technical expertise, trained personnel, record-keeping and inspection procedures.

Actually, Mexico has a pretty decent infrastructure in terms of airports, although these do pose some operational challenges of their own (things like high terrain, high elevation). The CAA was actually “revamped” back in 2019. We put out this post about ramp checks.

Mexico’s political problems seem to be at the root of most issues here for the aviation industry. A project to build a new airport was recently cancelled (Texcoco airport was partially constructed already.) Now the government are instead looking to improve MMTO/Toluca and build new runways at an Air Force base near Mexico City. Plans are also under way for a third terminal at Mexico City Juarez, but given it is already congested and operating over its designed capacity, this might not be any solution.

Combined with Covid Pandemic problems, the latest downgrade will mean a big financial impact for various Mexican airlines now unable to access the major Mexico-USA market, and the knock on effect from this might be further felt in the aviation industry there as a whole.

The Big Taco-way?

If you are operating into an FAA IASA Category 2 ranked country, doing your own risk assessment on the standards and compliance you can expect to experience there might be worthwhile.

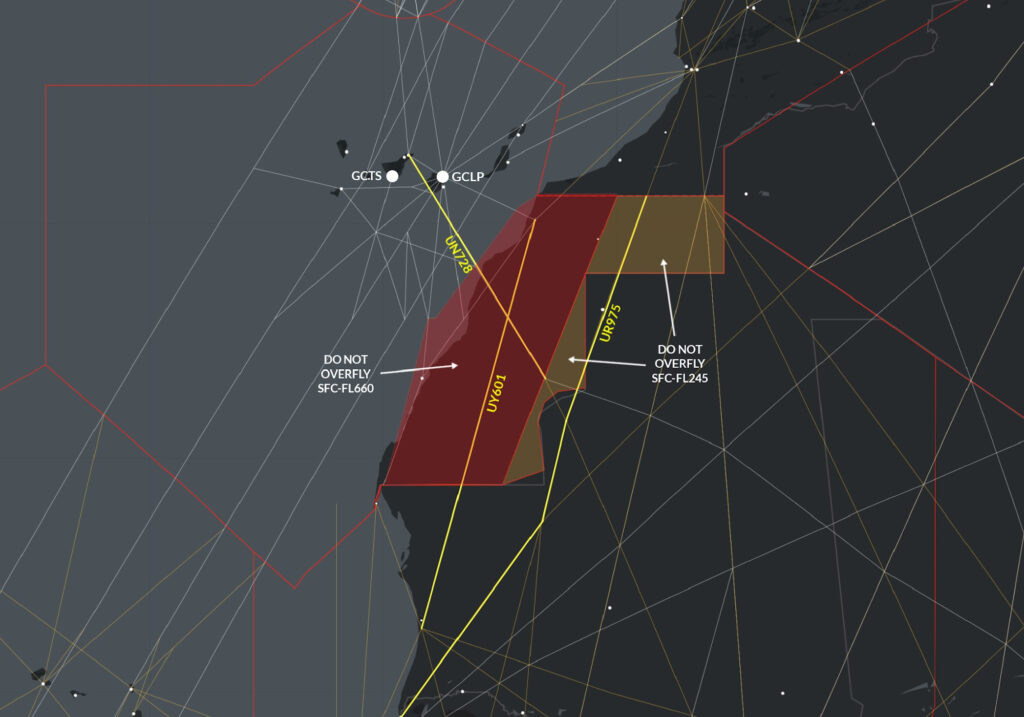

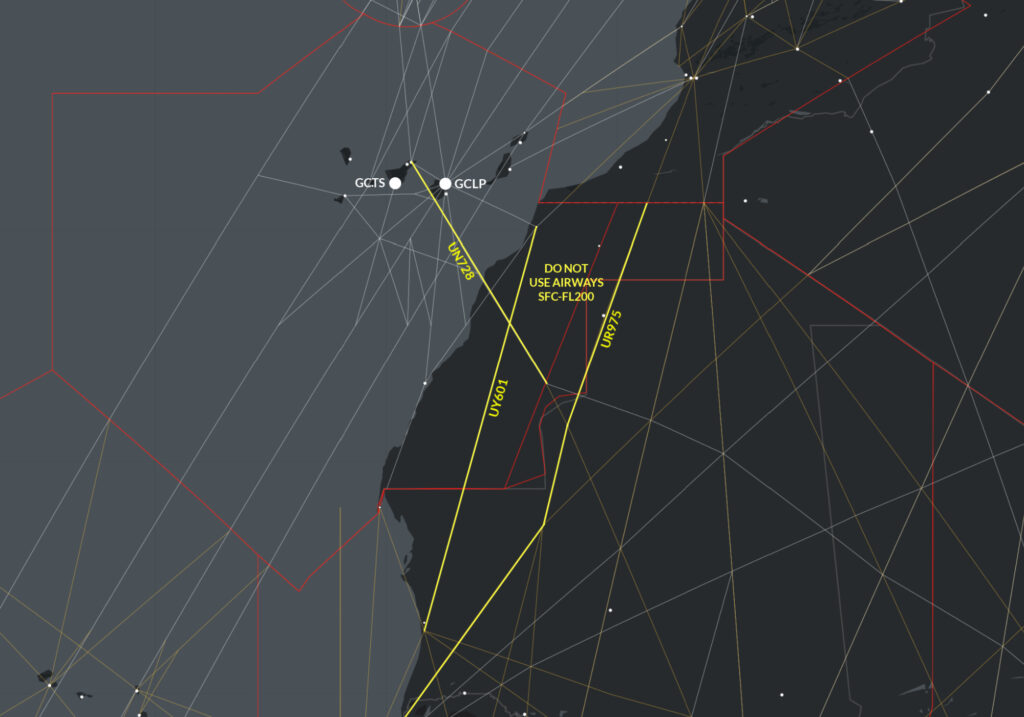

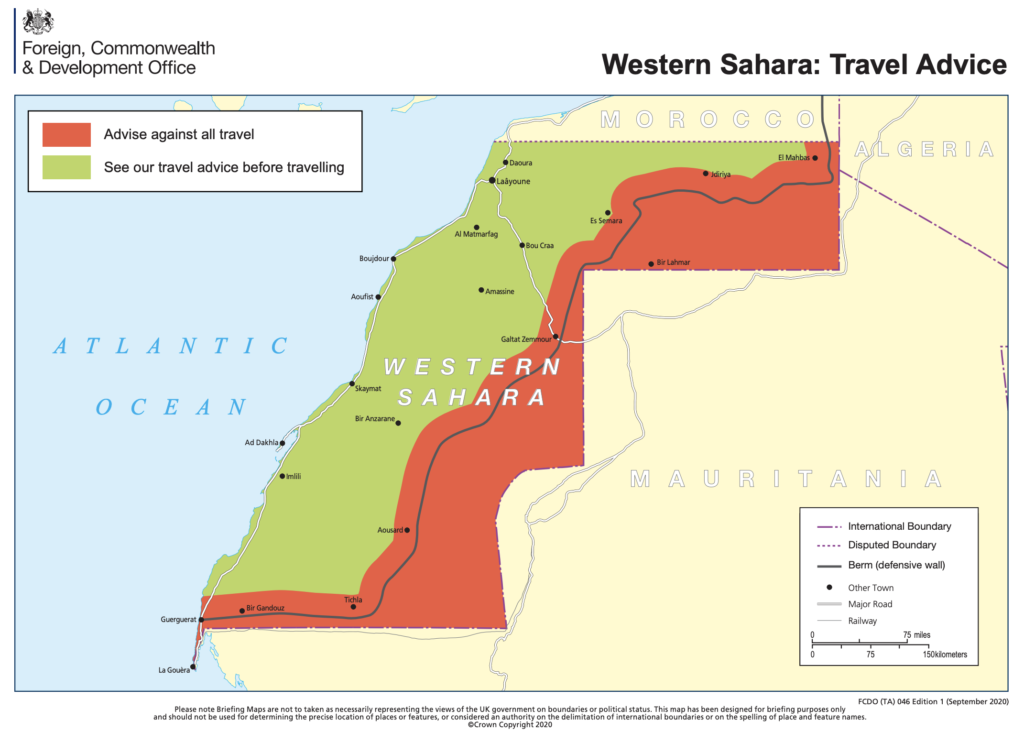

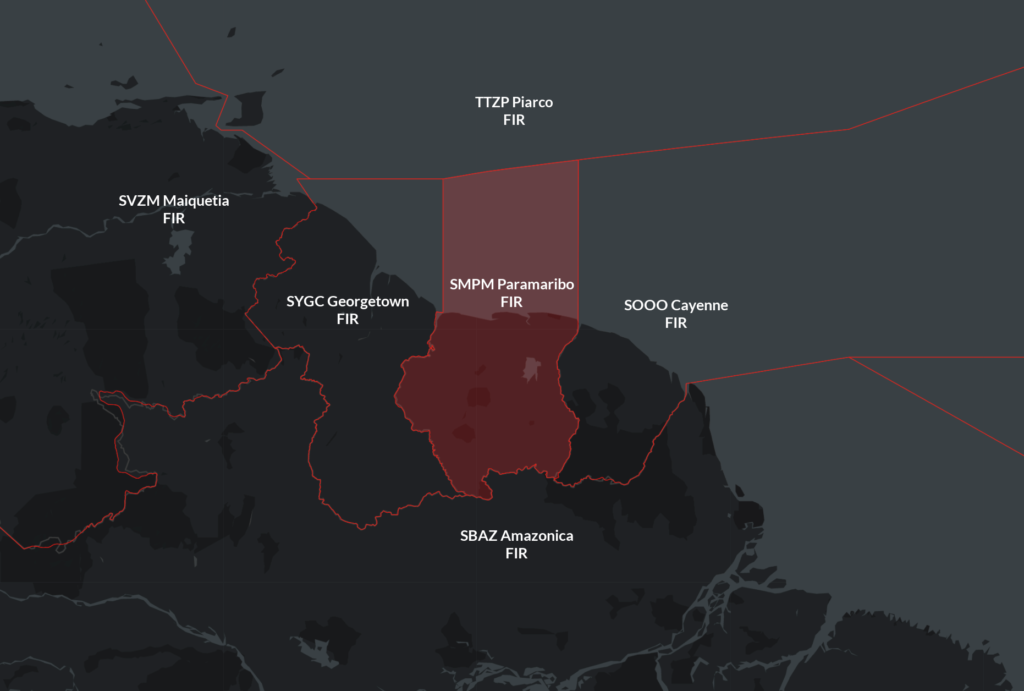

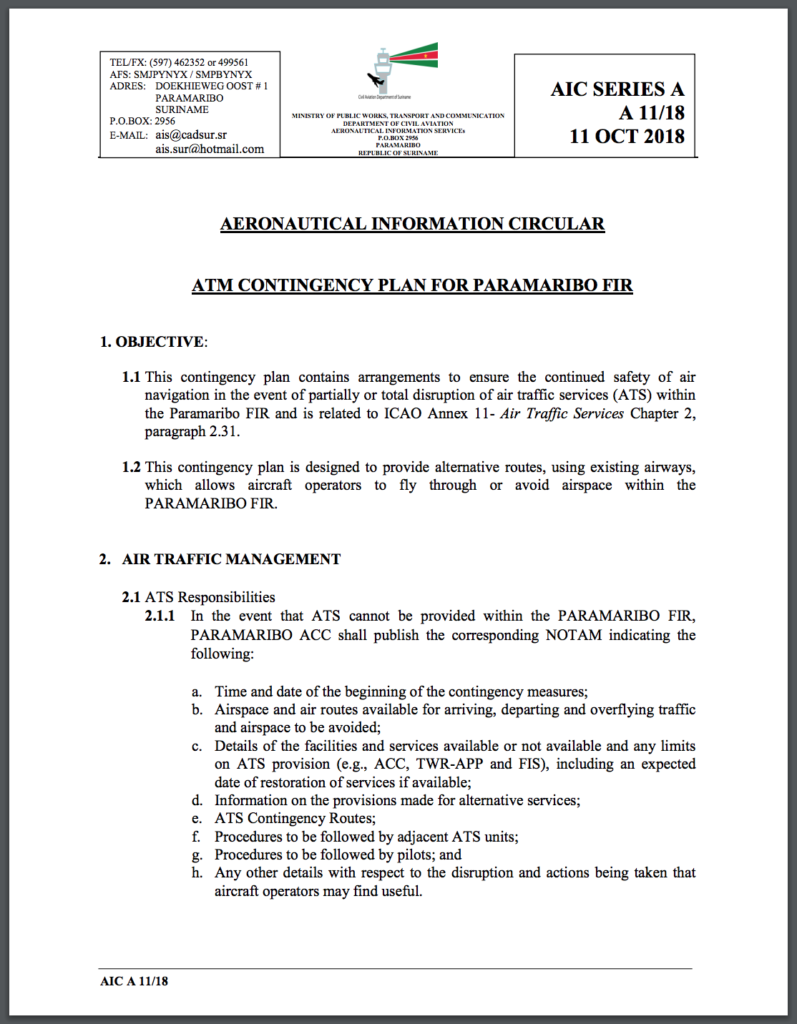

Procedures for the neighbouring ACCs:

Procedures for the neighbouring ACCs:

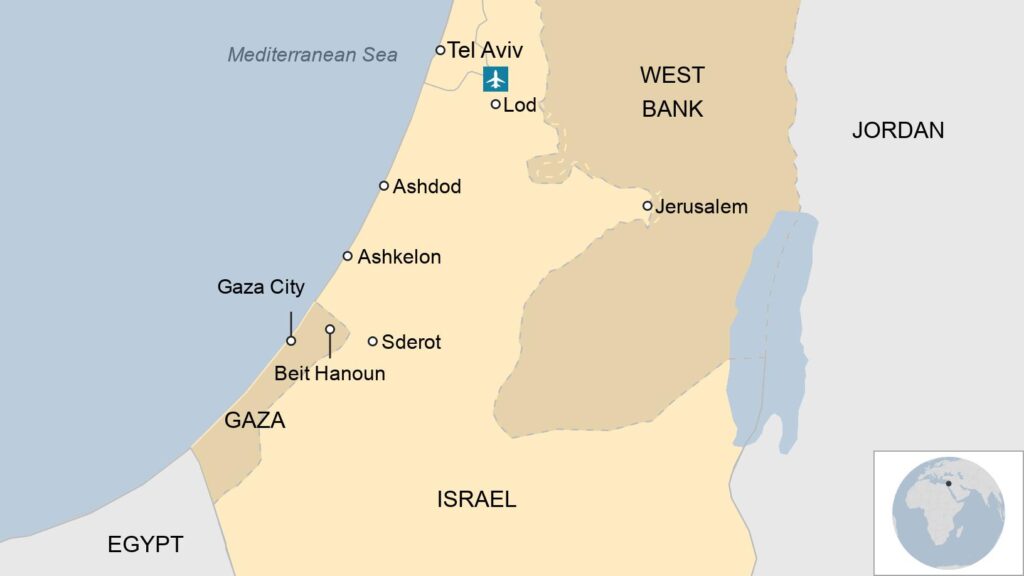

Israel has an Air Defense System – “Iron Dome” which protects populated areas of Tel Aviv from rocket attacks by launching interceptor missiles to ensure rockets detonate prior to reaching the ground, minimizing damage. However, the sheer number of rockets launched resulted in several impacting the city.

Israel has an Air Defense System – “Iron Dome” which protects populated areas of Tel Aviv from rocket attacks by launching interceptor missiles to ensure rockets detonate prior to reaching the ground, minimizing damage. However, the sheer number of rockets launched resulted in several impacting the city.