Update: The NOTAM campaign was launched with 1,500 attendees on April 8th – and yes, it was the largest virtual event in ICAO history! The first update webinar on progress being made is on June 16th at 1200Z – register with this link, and join the call.

The Global Campaign on NOTAM Improvement is being launched on April 8th, 2021. Spearheaded by ICAO, and supported by OPSGROUP, IFAIMA, and IFALPA, the campaign will focus on making significant improvements to the NOTAM system to enhance its effectiveness, usefulness, and reliability as a mechanism for pilots to receive critical flight information.

Kick-Off Webinar, April 8th 2021

At 1200Z on April 8th, 2021, we will launch the campaign with a worldwide webinar. So far, we have 600 registered participants. We are on track to make this the biggest virtual event in the history of ICAO. If you think about it, that’s pretty amazing for a meeting about NOTAM’s!

This webinar is open to everyone, and we would be delighted to have you join it – to show your support for the Notam Improvement campaign, to learn more about what the plans are, get the latest update, and see how you can get involved: this is a collaborative, shared mission that needs your help, whether you are a pilot, dispatcher, AIS officer, software developer, Flight Planning provider, ANSP, CAA, or are in any other way a user or provider of some aspect of the Notam system.

So, please join us – it’s open to all:

Register for the Worldwide Webinar on Thursday, April 8th, 2021 – 1200 UTC

1200 UTC = 7am Lima, 8am New York, 1pm London, 2pm Berlin, 4pm Dubai, 7pm Bangkok, 10pm Sydney, 12am Auckland.

Why should I join the Webinar?

Over the last few years, as many as 10,000 pilots and dispatchers have supported a move to fix Notams – through petitions, surveys, comments, emails, and joining the OPSGROUP Notam Team to help fix the problem. Your voice has been heard: this work is the result. Now, we need your support for this campaign – to reinforce the message that as an industry, we really care about this. Your presence will encourage those working on solving the Notam Problem, and you will get the full picture of where we stand in the progress to fix things.

We will speak about the mission, demonstrate the problem with some real world examples of pre-flight briefings, showing how these impact the daily lives of pilots and dispatchers, clarify the definition of “Old NOTAM’s”, and show how AIS staff can use the existing regulatory framework in Annex 15 and Doc 8126 to become a gatekeeper for NOTAM quality, demonstrate the Notameter, address regional challenges, and have a Q&A session.

Our presenters and speakers will include Stephen Creamer (Director of the Air Navigation Bureau at ICAO), Alex Pufahl (ICAO Technical Officer), Mark Zee from OPSGROUP, Capt. Lauri Soini from IFALPA, Fernando Lopes and Antonio Locandro from IFAIMA, Marco Merens from ICAO, and ICAO Regional Officers.

What is the Notam Campaign all about?

First, the problem: Pre-Flight NOTAM Briefing packages are often far too big to be fully read and understood by pilots before a flight. The result: critical information is missed. Finding safe ways to decrease that volume is the key focus of this campaign.

In the Global Campaign on Notam Improvement, our aim is to solve the Notam Problem in manageable chunks, gathering energy as we solve them and make progress. Rather than re-invent the wheel, we will fix the system from within, starting with the easier aspects and progressing from there. The first phase of this campaign focuses on Old Notams. At any one time, there are about 35,000 active Notams globally, and 20% of these – one in five – are old; in other words, not respecting the existing rules of Notams being issued in principle once only for a maximum of three months (everything else should go into the AIP, an AIC, or some other publication).

We are drawing on the collective cooperation of the AIS community – the Notam Officers – to uphold the rules and get rid of Notams that don’t follow them. The result will be a potential decrease of 7,000 Notams per month, and a 20% reduction in the size of the average briefing packet. For more on the Notam Problem itself, have a look at “Why pilots are reading a Reel of Telegrams in the Cockpit“.

Who is behind it?

The Global Campaign is a meeting of minds, agreeing on one thing: Notams need fixing.

ICAO is spearheading the campaign, in the recognition that the Notam Problem is a worldwide issue that affects flight operations in every country.

Providing support, energy, and huge enthusiasm to help solve things are IFAIMA, representing the Aeronautical Information community, IFALPA, voicing the concern of Airline Pilots, and OPSGROUP, whose pilot, dispatcher, and flight operations members have been tirelessly involved in the mission to fix Notams since 2017.

What can you do to help?

Thank you for asking! If you are in the AIS community – perhaps as a Notam Officer, AIS Officer, Publisher, or Promulgator – please tell your colleagues, join the webinar, and get involved in this Campaign. If you are a Pilot or Dispatcher, join the webinar, share the news of this campaign (#NOTAM2021), voice your support, and monitor progress – we’ll want your help down the track as well. If you are a Flight Planning Provider or Software Developer – again, join the webinar, and when the time comes, get involved in the collaboration around technical improvements. If you work for an ANSP or Civil Aviation Authority – join the webinar, encourage your colleagues to join too, and help support the Campaign. If you work for an Organziation, tell your members, and share news of this campaign (#NOTAM2021). Oh, and join the webinar!

How we got here …

This is a Global Campaign for a very good reason. We only solve this problem when we solve it for all countries – so we take the lessons learned domestically from those countries that have seen NOTAM wins, and amplify that across the rest of the globe.

In terms of change so far, most notable is the work done by the AIS Reform Coalition in the United States, chaired by Heidi Williams from the NBAA. This group of people from NATCA, ALPA, AOPA, IATA, A4A, ACI, the NBAA and others have been working feverishly in partnership with the FAA to drive change and improvement. And it has had remarkable results – the US has radically improved NOTAMs in the last 2 years: NTAP gone, a big reduction in PERM Notams, a single office for AIS, a transition to the FNS, and NOTAM Search replacing Pilot Web. Canada has transitioned to ICAO format for Notams, and provided a new delivery mechanism through CFPS.

We must also recognise huge efforts from the members of OPSGROUP, who as pilots, dispatchers, and other flight operations specialists have made their voice heard, sharing support, input, ideas, and enthusiasm for change; the efforts of IFALPA to bring attention to the issue, and IFAIMA who have given full support to solving things on the AIS side.

An important distinction to make here is that this work is on “NOTAMs, Now“. There is separate, ongoing work in the field of the “Future of NOTAMs”. You may have seen acronyms like SWIM and AIXM, and terms like Digital Notams or Graphical Notams. The FAA, ICAO, Eurocontrol, and other agencies are building a model for the future, when NOTAM’s will change from the current AFTN format and transmission into an internet, IP based, transmission and follow a service-oriented approach. This work is valuable, but with a target implementation date of 2028, has a different focus. Even if it goes smoothly, it would not instigate change until 2028. Needless to say, if we don’t fix the underlying issues now, it may not even solve them then, either.

The AIS Community, Pilots, and Dispatchers, working together

Here’s the really exciting part of this Campaign: for the first time we are seeing pilots, dispatchers, and AIS staff working together on solving the issue. This is a core tenet of the campaign: only when you have all parties involved, do you have a shot at success.

The AIS Community is invaluable in solving the problem, but they need our help. First, they need to know exactly the impact of the Notam Problems we describe – this drives their will to make change and improvement. Second, they need the support – which this Campaign will provide – to stand as gatekeepers for Notams. They themselves are often under pressure to publish Notams that they know don’t align with the rules, but have no alternative.

Phase One

So, once the Campaign is launched, what does the roadmap look like? Logically enough, we start with Phase One. A simple, bite-size chunk of the problem – Old NOTAM’s. In volume terms, it’s a lot more than bite-size – it’s actually 20% of the problem. The key is that it’s easy to understand, and therefore easy to work on. We don’t need to make any structural changes, or change how the system functions. This is simply about focusing on a known issue – that 7,000 of the 35,000 active Notams that should not be there.

Even more importantly, the focus is also on the energy, enthusiasm, and goodwill to make the changes necessary. As we gain momentum, we get encouragement from each and every Old NOTAM that is removed forever. We see that through collaboration, community, and support for each other, we can make change happen.

Remembering that this is a decades old problem that has been on the agenda since 1964, and that there are 193 countries on this journey, progress may feel slow at first. But we’re going to learn from each other, and go as fast as feels right. We’ll be celebrating the small wins!

Phase Two

The next phase will look at technical improvements. In other words, what structural and systemic changes can we make to NOTAM’s to leverage quick improvement.

We envision that this stage will be best served by a great deal of collaboration and discussion. One of the key groups here will be Flight Planning software providers. The vast majority of NOTAM briefings today are provided by these companies. As things stand, each one has a different, in-house method of processing the Notam flow – usually with algorithms, keyword searches, date/time validity ordering, and some Q-code assessment. So we might ask, how can we best structure the Notam data to provide a robust, reliable format with metadata that allows sorting and filtering – the two big asks from the pilot community. In other words, show me the critical stuff first, and skip the fluff.

We also, again, need full collaboration with AIS to see what the impact of those technical improvements will be, and whether they support them. Adding pilots and dispatchers into the mix will allow us to verify that the changes being discussed will actually have an impact by the time they reach the cockpit. If they don’t, then we’re not doing it right.

More about #NOTAM2021

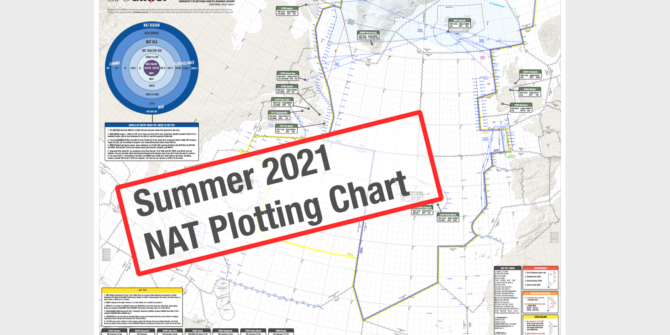

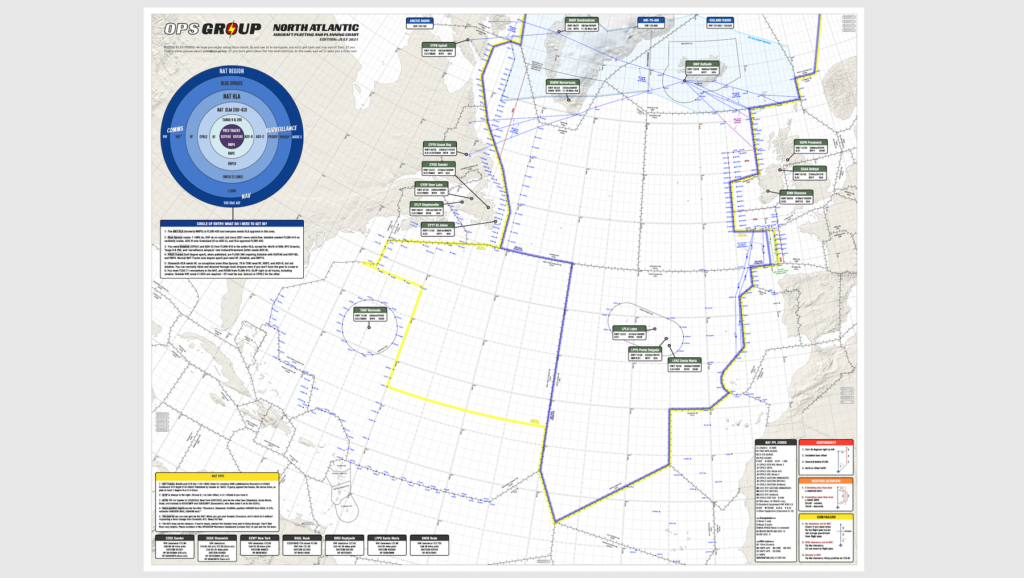

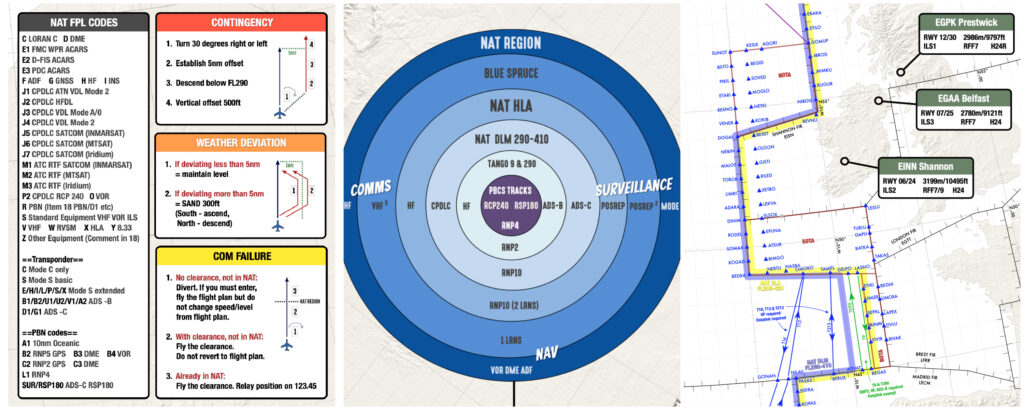

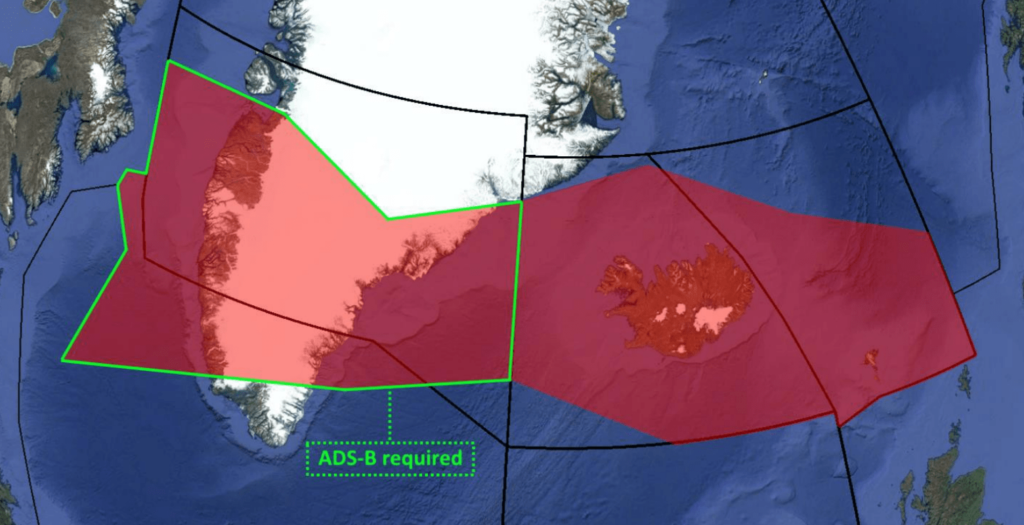

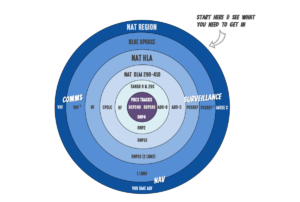

Confused? We don’t blame you. Here’s something that might alleviate some misery though – our NAT Airspace Circle of Entry. OPSGROUP members can download the full hi-res PDF version

Confused? We don’t blame you. Here’s something that might alleviate some misery though – our NAT Airspace Circle of Entry. OPSGROUP members can download the full hi-res PDF version