Have you ever taken a look at a report listing the distribution of Accidents by Accident Category? There are apparently more than 40 possible ways an accident can be categorized, but there are 7 that seem to pop up way more often than any other.

Airbus took a look into all fatal and hull loss accidents which occurred between 2009 and 2019 and the results are shocking in that a lot of those accidents just should not have happened.

P is for…

Yep, pilots. We are a big problem. We mess up a lot. That is what seems to be said in the media anyway…

But, it isn’t always our fault, (sadly some of the time it also is), and we all know that the news reporter’s favorite phrase “pilot error” (or “human error” if they are feeling particularly generous about it) is rather meaningless, and very unfair. It removes all the context of the why’s and the how’s of what led to a pilot making an error, and it is rarely ever as simple as “they just messed it up.”

There are usually countless small things that lead up to any incident, and many a CRM course has been spent discussing and brainstorming how we can better avoid all of these little things and so avoid it ending up in a “one big thing” event.

So, why are these big events still happening? And what can the pilot in the equation do to prevent them? (Because the vast majority of these definitely are preventable).

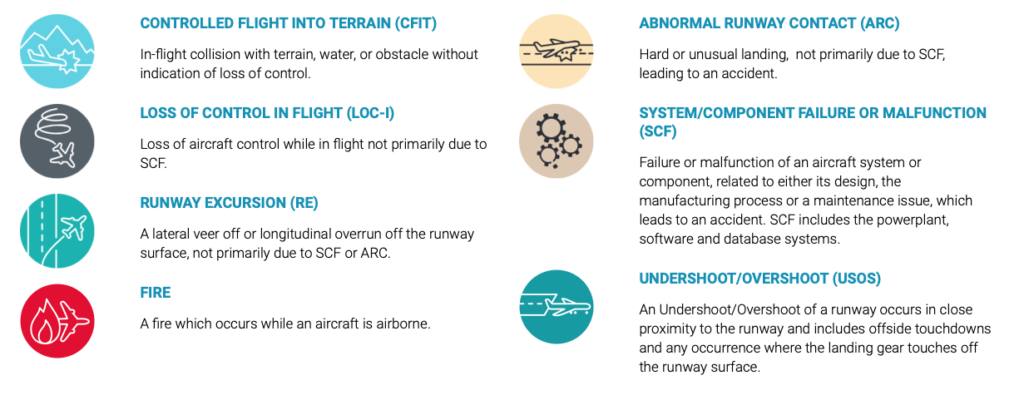

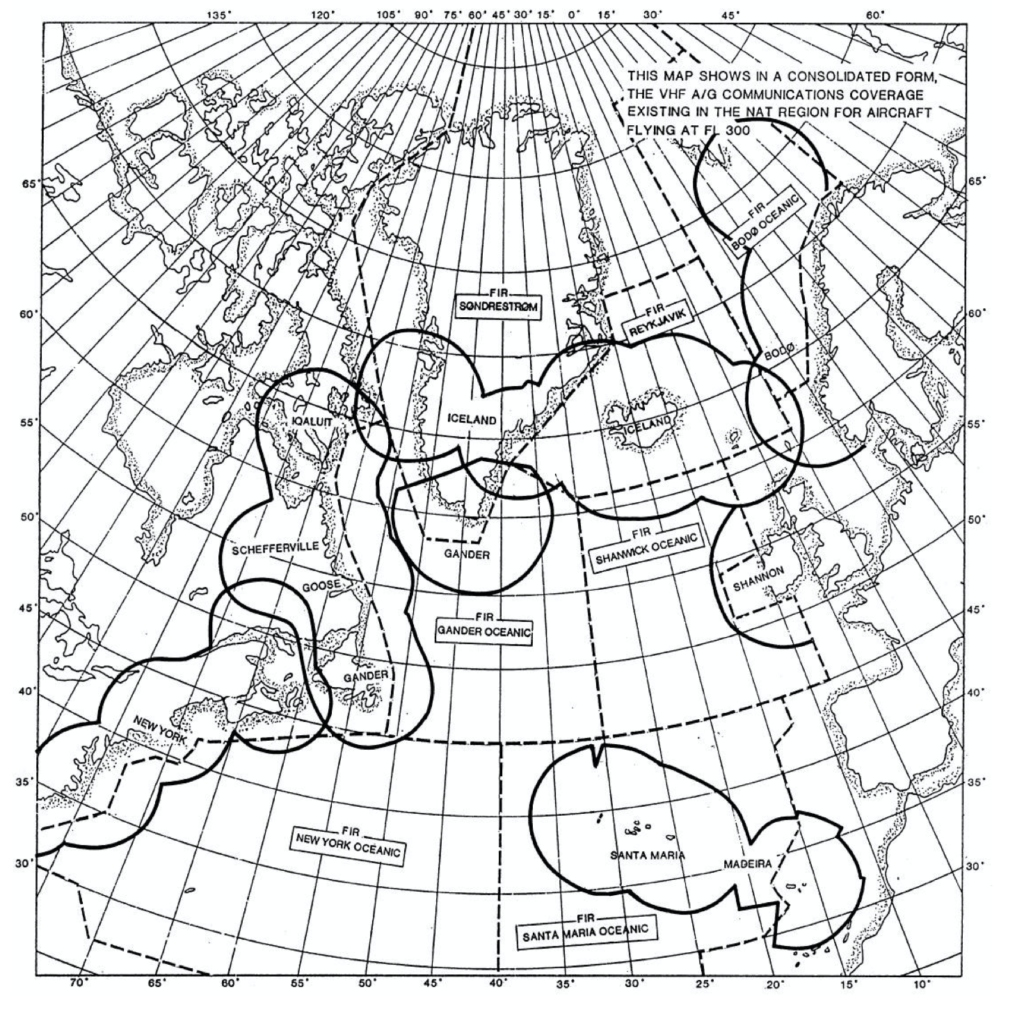

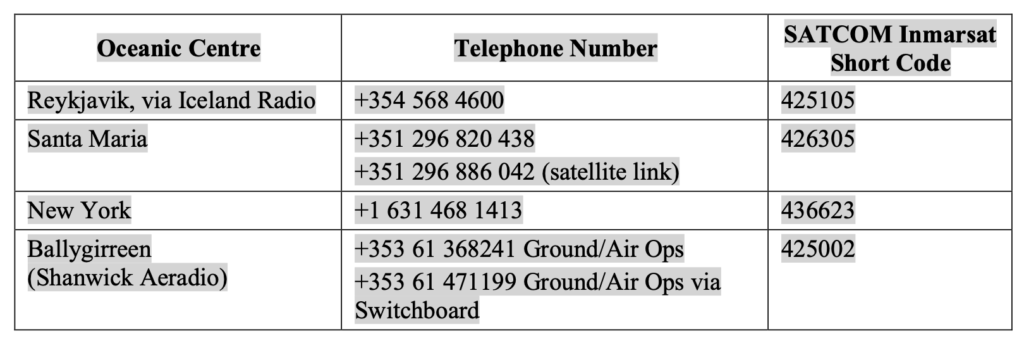

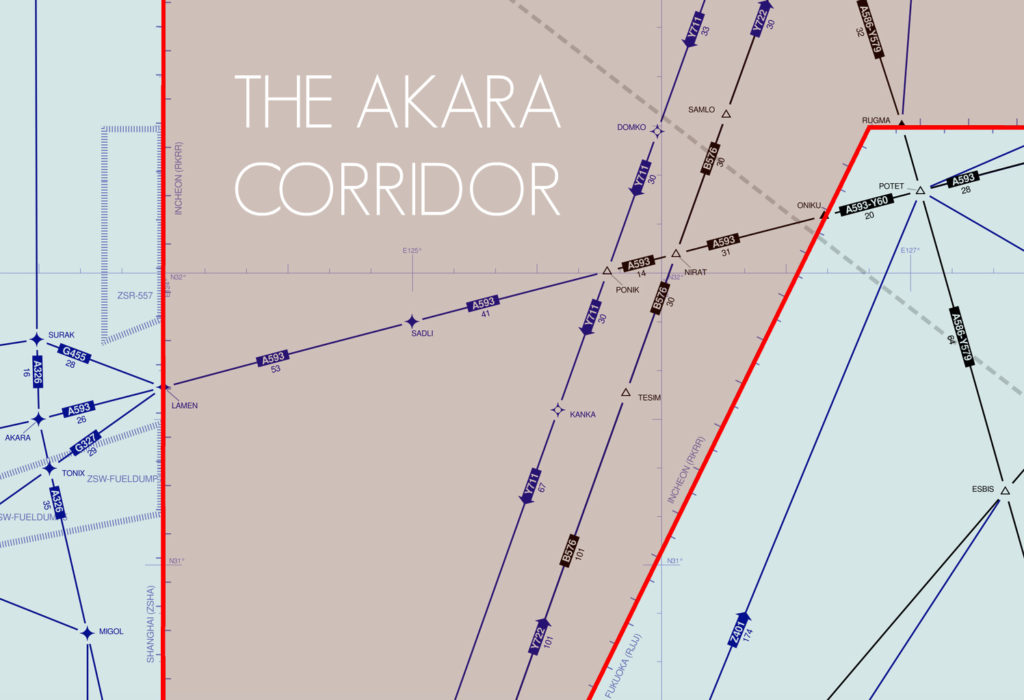

Taken from the Airbus report

1. Loss Of Control In Flight

This is the single biggest cause of fatal airplane accidents in this period, accounting for a scary 33%, and 12% of hull losses. We are not talking about situations where something major has broken or failed – we are talking about times where aircraft have somehow managed to get into a situation they shouldn’t be in, and the crew have not able to safely get them out of said situation.

Air France Flight 447 is one of the most discussed examples of this occurring.

All these accidents no doubt had other factors involved – it was not just the pilots not knowing how to fly. There were things like startle factor, bad weather, other warnings, other traffic…

But a large number of these could have and should have been recoverable.

So, what can we do about this? Well, ICAO took an in-depth look at why these kept happening, and they came up with a great and simple thing – UPRT.

Upset Recovery and Prevention Training

When they say simple they really mean it – all you really need to know is PUSH, ROLL, POWER, STABILISE (and maybe have had a few practice goes in the sim).

This is the recovery though. It is the point when everything has gone wrong and all you have left is fixing it.

Luckily, we pilots do have a few other tools in our toolbox which we can pull out earlier at a time when prevention might still be possible. Things like good monitoring, situational awareness, an understanding of startle factor.

In fact, we have a post right here if you’re up for some more reading on the old startle thing.

There is also that Other thing we can do. It might be one that makes a few palms get a little sweaty at the thought of it – but we can disconnect the autopilot and actually hand-fly now and then.

2. Controlled Flight Into Terrain

Second on the list of the ‘7 Deadly Things’ is Controlled Flight Into Terrain. Again, not because something has broken, but because a crew have just totally lost their situational awareness. These account for 18% of all fatal accidents, and 7% of all losses reviewed in the 20 year period.

The Korean Air Flight 801 accident report offers more insight into how these occur.

Again, other things factor into this – distractions, visual illusions, somatographic illusions – and these can be tough to handle because they are one of the few things a simulator cannot realistically simulate.

We have backups though. GPWS for one. Although this really is the final layer of the safety net. If this is going off then you’re out of the prevention and well into the recovery and mitigation part of the accident curve.

There is good old Situational Awareness again though – this is the stuff of heroes. It is something you can gain, or regain, with a simple briefing. A “What if… then what will we do?” chat. Briefing threats is important, but briefing how to avoid them is even better. Get a bit of CRM in and ask the other person next to you what they think you should be looking out for.

Situation Awareness is knowing where you have told your plane to go but, most importantly, it is knowing if it is actually going there (and this means vertically and laterally).

3. Runway Excursions

These account for 16% of fatal accidents, and a whomping great 36% of hull losses. No failed brakes or issues with steering involved, just big old “oops, didn’t check the performance properly” type situations. We have mentioned this before. It is one of the biggest “that just shouldn’t have happened” types of event.

Actually, the biggest thing that leads up to runway excursions is generally unstabilised approaches. These are something we can definitely avoid and IATA has some great tips on how. Cut out the unstabilised approaches and you’ll probably cut out a big proportion of runway excursions right away.

There are a few things to help us here too – if you are flying an Airbus then lucky you, because these have a great system on them called ROW/ROP that squawks at you on the approach, and on the landing roll, if it reckons you’re going to go off the runway. But if you don’t have this, then checking your performance properly and managing that approach well are going to be what saves you from an embarrassing call to your chief pilot.

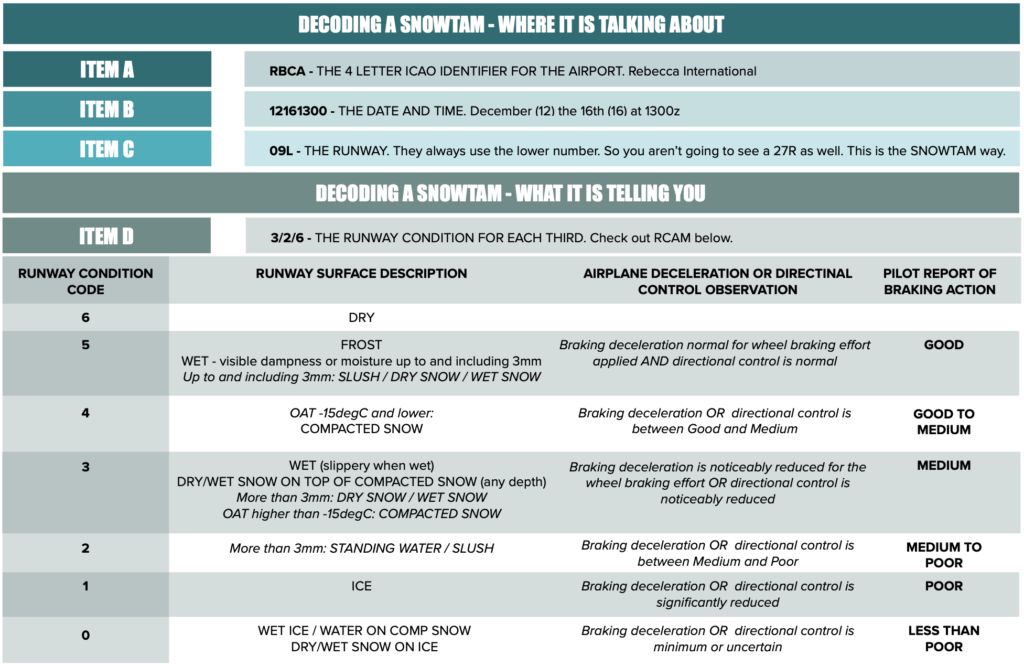

There is also a big change to runway friction reporting coming in on 4th November 2021 – The Global Reporting Format, or ‘GRF’ as he is known to his friends. Griff will standardize how runway surface conditions are reported worldwide and with better reporting will hopefully come better awareness of the risks.

Being aware of what you’re landing on is pretty important!

That was the Top 3. What about the others?

The other four are lumped together into ‘Other’ which makes up the remaining 33%. (Actually, 11% of that is ‘other’ others!) Combined, our final four account for 22% of all fatal accidents and 22% of hull losses.

These are:

- Fire

- Abnormal Runway Contact

- System/Componet Failure or Malfunction

- Undershoot/ Overshoot

Now, I know what you’re going to say – fire probably isn’t your fault (unless you dropped your phone under your pilot seat and then ran over it repeatedly with your chair trying to hook it out again).

But there are still things a pilot can do to help lower the impact of these.

How? Well, by knowing our fire procedures (the what to do if something Lithium Ion powered in the flight deck does start smoking), and by knowing the comms procedures needed to help support our cabin crew if there is something going on down the back. We can also prepare in flight – be ready with something in the secondary flight plan in case we need to suddenly divert.

As for system and component failures, well, the 737Max accidents of the last few years account for a big proportion of this, however, in all cases having a strong systems knowledge and preparing for those “what if?” situations might help save your life one day.

You might have noticed a shift in the training paradigm in the industry, and with good reason – the days of focusing on practicing specific failures in the sims are vanishing and in its place is Evidence Based Training – training that focuses on building the skills needed to handle any situation. If that all sounds newfangled to you then think of it this way – a pilot is there just not to push buttons, but to manage the flight, and these skills are the tools which will enable us to do that.

Fancy reading some more?

- A full report from IATA on LOC-I can be found right here

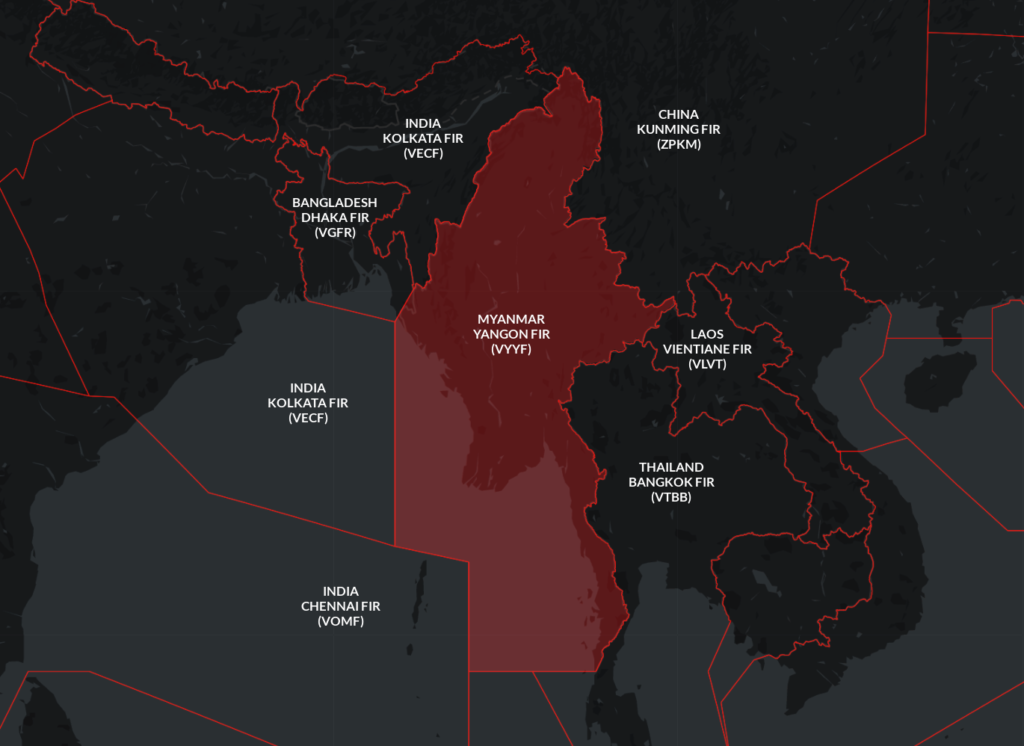

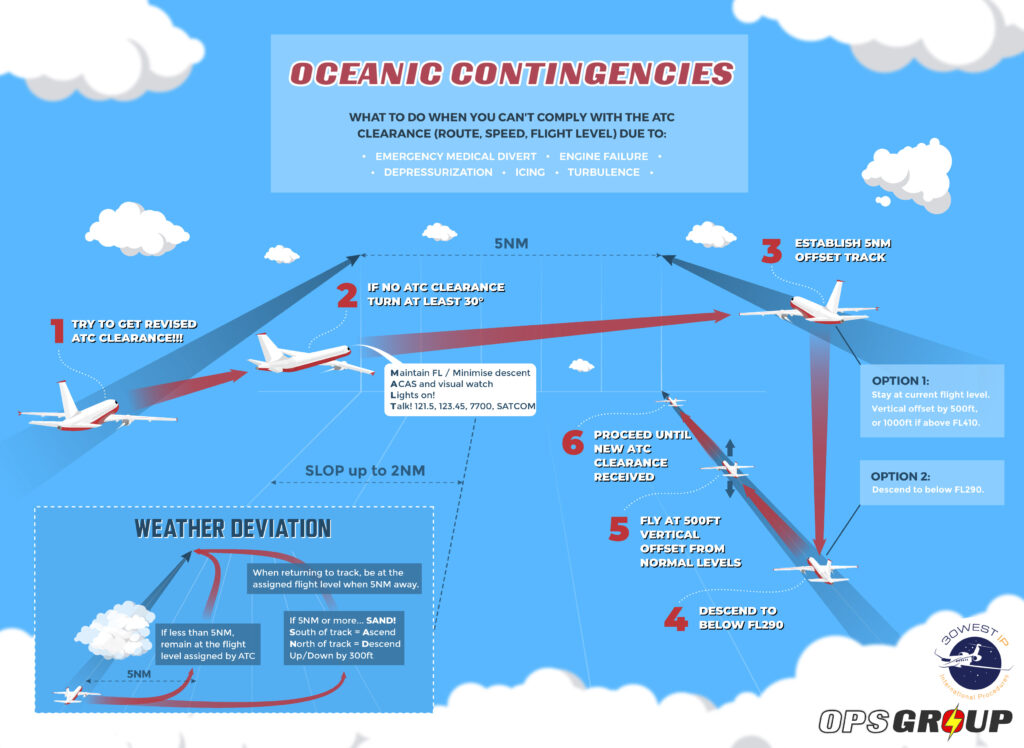

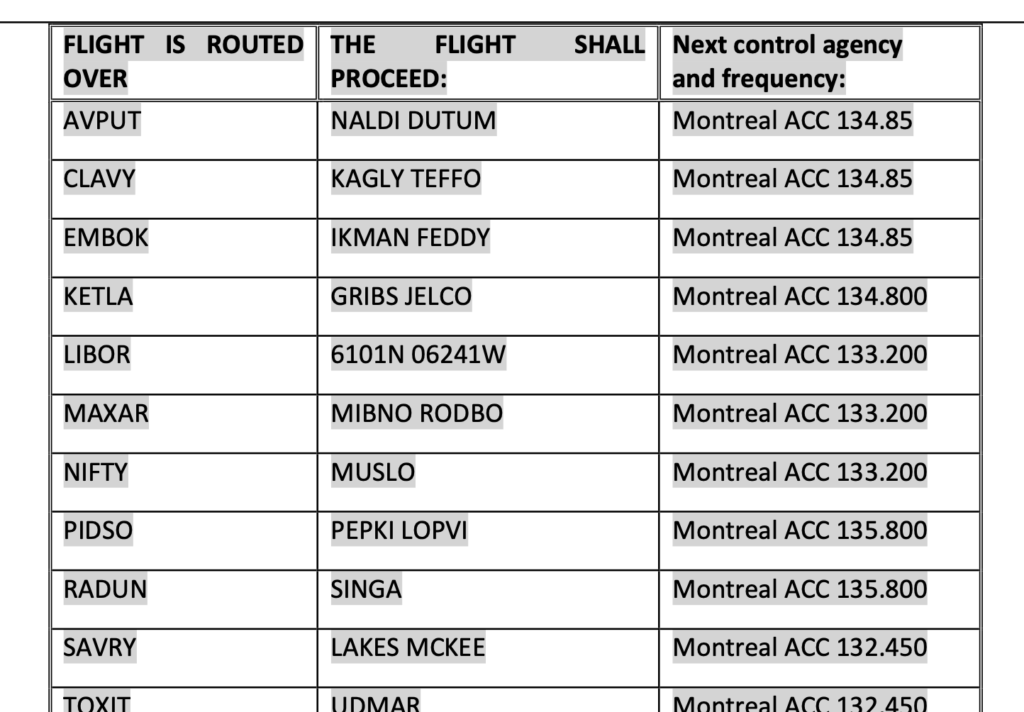

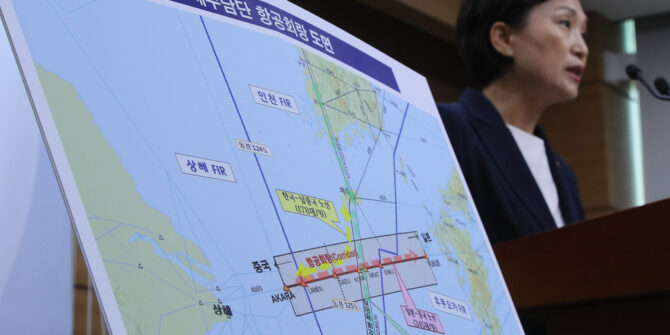

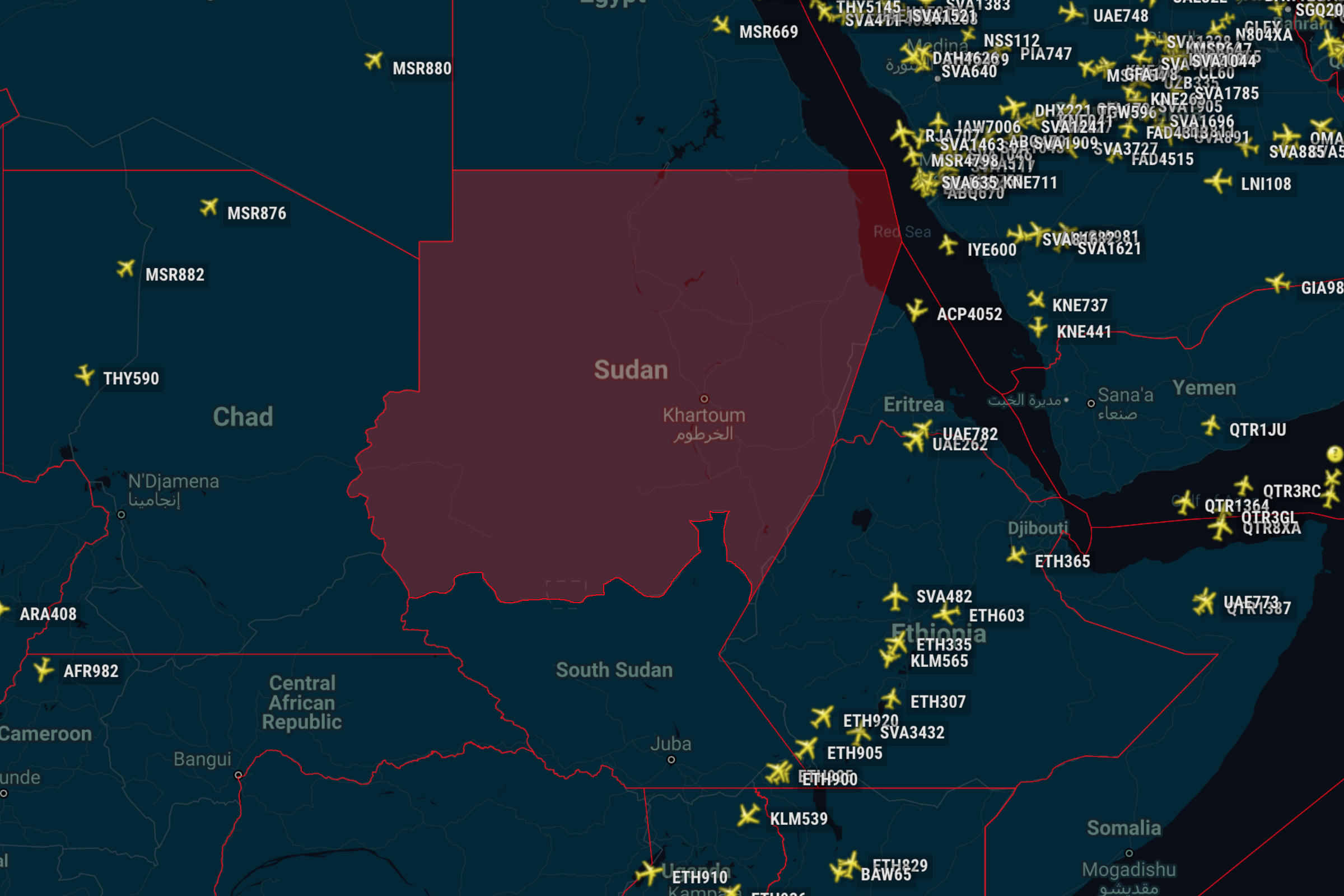

And here’s the info on the Contingency Routes in effect, as published in the

And here’s the info on the Contingency Routes in effect, as published in the

A is for Airplane, flying high as a bird

A is for Airplane, flying high as a bird B is for Bureaucracy and unreadable words

B is for Bureaucracy and unreadable words C is for Covid not going away

C is for Covid not going away D is for Datalink on the NAT HLA

D is for Datalink on the NAT HLA E is for Errors of the Gross Nav variety

E is for Errors of the Gross Nav variety F is for OpsFox, a secret society

F is for OpsFox, a secret society G is for Guy Gribble, gone too soon

G is for Guy Gribble, gone too soon H is for Humans, me and you

H is for Humans, me and you I is for Israel overflight clearance

I is for Israel overflight clearance J is for Jamming and GPS interference

J is for Jamming and GPS interference K is for Kiwis showing us what to do

K is for Kiwis showing us what to do L is for Lockdown, no kiwi for you

L is for Lockdown, no kiwi for you M is for Members, colleagues and friends

M is for Members, colleagues and friends N is the Notam problem again

N is the Notam problem again O is for OPSGROUP, share what you know

O is for OPSGROUP, share what you know P is for Pilots flying us home

P is for Pilots flying us home Q is for Quarantine in a government compound

Q is for Quarantine in a government compound R is for Relief Air Wing, eyes on the ground

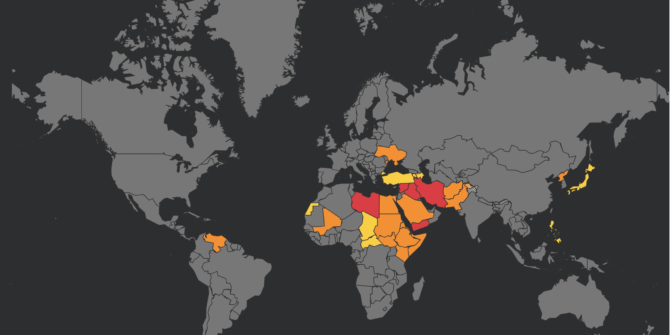

R is for Relief Air Wing, eyes on the ground S is for SafeAirspace, where not to fly

S is for SafeAirspace, where not to fly T is for Towers, controlling the skies

T is for Towers, controlling the skies U is for Unreliable speeds on aircraft stored too long

U is for Unreliable speeds on aircraft stored too long V is for going Viral when you do something wrong

V is for going Viral when you do something wrong W is for Winter Ops, cold weather tips

W is for Winter Ops, cold weather tips X is for Space X, launching their ships

X is for Space X, launching their ships Y is for a big Yes to 2021

Y is for a big Yes to 2021 Z is for Zoom calls – sometimes they’re fun!

Z is for Zoom calls – sometimes they’re fun!