Airport security means the threat of a bomb onboard is greatly reduced. But if you do receive a bomb threat, or find a suspicious package onboard, what procedure does your operator have in place for you to follow?

How much risk is there?

You have probably all heard the Shoe Bomber attempt from 2001. This was thwarted by some brave passengers and crew, and also the fact the bomber had sweaty feet – his swamp foot dampened the trigger preventing it from igniting.

In 2016, an aircraft made an emergency at HCMM/Mogadishu airport after a bomb exploded onboard. The bomb was likely brought on concealed within a laptop. This flight was lucky though – the impact of the bomb was minimal, limited because the bomb exploded while the aircraft was at a lower altitude (11,000ft).

In 2020 a European airline found a ‘bomb note’ onboard. The flight was escorted to a safe landing and passengers disembarked without incident.

So bomb threats, and attempted bombings, do occur, and while security is getting better and better, unfortunately terrorists are getting more creative in finding ways to bring items on board. The attempts are not always aimed at causing destruction either – threats alone cause a huge amount of disruption to operations. So understanding how to assess the risk and credibility of a threat is as important as knowing how to deal with a possible explosive device if one is found onboard.

Is the threat credible?

Threats received regarding an aircraft need to be assessed, and the credibility determined. The threat classification will generally be based around how specific the threat is. Most operators will have a procedure in place for determining this, and probably take into account something along the following lines:

If a threat mentions a specific target, or is made by a known terrorist organization and is deemed credible then this is going to be considered more serious. Often these are referred to as a red threat.

On the other hand, a threat which is vague, general, and doesn’t specify targets might be considered less credible. A hand scribbled note in the toilet for example. This would be categorized as a green threat.

However, regardless of the assessed credibility, a bomb threat has to be taken seriously and treated as a genuine situation.

If you are on the ground

The simplest and safest option if you are on the ground is to disembark and carry out a full search of the aircraft. It might be a hassle and result in some big delays, but the possible alternative is much worse.

A serious threat may require a precautionary disembarkation – which will result in offloading the passengers as quickly and as safely as possible. This creates a risk to safety in itself, and generally the credibility of the threat will be communicated to the crew so that they can judge the risk of waiting (for steps) versus disembarking immediately to clear the aircraft (but have passengers hurling themselves towards the tarmac).

If you are in flight

If a threat is received against your aircraft while in flight, carry out a search checking those places which are often overlooked during security checks on the ground, but where an article might easily be concealed – toilets, galleys, jump seats, stowage areas, closets etc. Try and do it discreetly to avoid unnecessary worry for passengers.

If an article is found, do not move it or touch it. Move passengers away from the immediate area, and remove any flammable items and have fire extinguishers ready in case. A PA asking for anyone onboard with ‘BD or EOD experience’ might help – these are terms which experts will recognize without saying “Hey, passengers, is there a bomb expert onboard?”

Not terrifying your passengers is probably a good call, but ensuring they are following your crew’s orders, and that they are prepared for the situation on the ground, is also necessary. This means providing them with clear information, but without dramatizing the situation.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, we have received a message that a threat has been made against one of our aircraft/an aircraft in this airspace. These threats do happen, however, until we can establish how credible it is, we will take all possible precautions and therefore intend to land at… in…”

If you find a suspicious article

Most manufacturers provide checklists for bomb-on-board situations. Know where this is, and understand what it says.

There are a few measures you might want to consider:

- Talk to ATC so they know exactly what is going on and what you need. They all assist with locating an airport with services needed, and coordinating with military if necessary.

- Try to avoid routes over heavily populated areas.

- Consider carefully the choice between flying fast to minimize airborne time versus flying slow to minimize air-loads and damage (in the event of fuselage rupture).

- Request remote parking on the ground if there isn’t a designated bomb location.

- Brief your crew for a possible emergency landing, and in any event, brief them to ensure passengers are disembarked quickly and moved to at least 200m upwind from the aircraft.

- Avoid large and rapid changes to pressure altitude – consider using manual cabin altitude controls to minimize rapid pressure changes while still lowering the cabin altitude to reduce the differential pressure.

Aircraft are designed to not ‘explode’ if there is a rupture in the fuselage – that’s why they tend to have a lot of smaller sections attached together. It makes the overall structure more resilient to the effects of an explosive decompression, aiming to keep it “localized”.

Reducing the differential pressure to around 1 PSI will also reduce the damage if an explosion does occur. Maintaining a slight differential will ensure the blast moves outwards, but the lower differential limits the force of air from the cabin outwards.

1psi is the equivalent of about 2,500 feet difference, but flying at an altitude that allows you to manually reduce the differential will probably mean a much lower level and much higher fuel burn.

Where is your aircraft’s LRBL?

A Least Risk Bomb Location is an area where the least damage will occur should a bomb explode. This should be specified in your aircraft manual. These are often near aft doors or in washroom stowage areas. The area provides the least risk, in the event of an explosion, to flight critical structures and systems.

If the article is deemed unsafe to move, cover it in plastic to prevent any liquids getting in, and then pile blankets and pillows, seat cushions and soft clothing around it. We’re talking as big a pile as you can, and once done, saturate in water to minimize fire risk in case an explosion does occur. Don’t forget the plastic sheets first though – liquid damage to electrical components is also a big risk.

If you can move it, and only if it is deemed essential to do so, then check that LRBL. Once in place, build up the barricade.

Always minimize movement to any article as much as possible, and don’t put anything directly on top of it. An igloo of saturated cushions around it and the gaps stuffed with blankets etc is good. This ‘cushioning’ will help minimize the force if an explosion does occur. Never put inside an oven or trolley though as a sealed container will amplify the pressure and explosive force of a bomb.

Where to go

You will likely be accompanied by fighter jets to an airport with a designated bomb area – usually a remote apron away from buildings, fuel supplies and other aircraft.

What next?

Getting your aircraft safely on the ground is Step One. Getting your aircraft to a safe point to disembark/evacuate your passengers and crew is Step Two and coordinating this with ATC and airport services is important. Knowing in advance where you will taxi to will get you there more quickly and safely. Landing, slamming on brakes and bursting tires will get you nowhere fast, so plan ahead and be prepared.

A bomb threat or bomb onboard situation is difficult to plan for because the ‘where you are and what will happen’ is not something we can prepare for, other than being ready to follow our procedures and remaining calm. Chances are this is not a situation many of us will (thankfully) find ourselves in, but understanding the resources you have to assist, and knowing the onboard procedures so you can coordinate passengers and crew will no doubt help if it ever does occur.

No restrictions on overflights have been published, with flight tracking still showing sporadic airline traffic overflying– although the bulk appear to be transiting further east over the Dominican Republic.

No restrictions on overflights have been published, with flight tracking still showing sporadic airline traffic overflying– although the bulk appear to be transiting further east over the Dominican Republic.

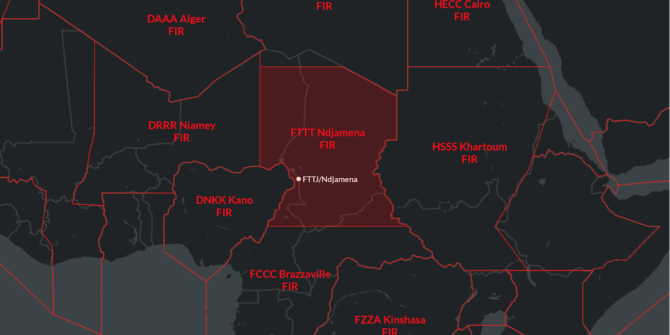

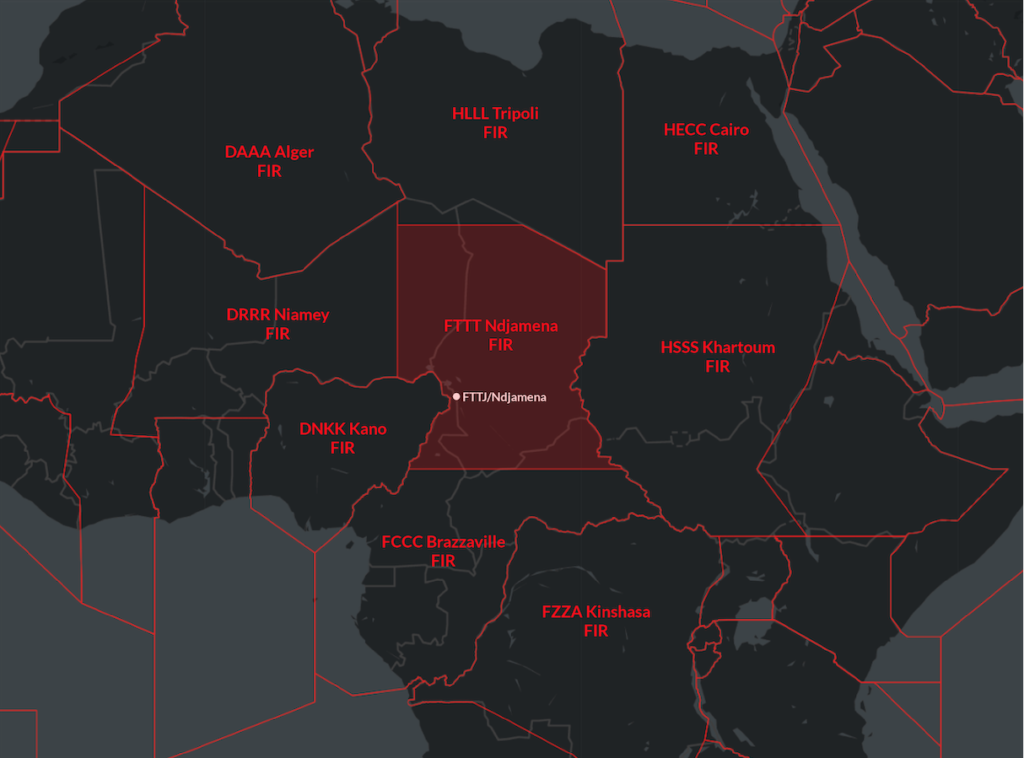

However, Chad is also one of the poorest nations in the world, with big problems around poverty, corruption and human rights, and with that came civil unrest.

However, Chad is also one of the poorest nations in the world, with big problems around poverty, corruption and human rights, and with that came civil unrest.