Wave at the ATC tower, and you might find there is no-one in to wave back. But that does not mean air traffic controllers are not watching us anymore, they just might be doing it from somewhere a little more remote.

The rise of the remote controller

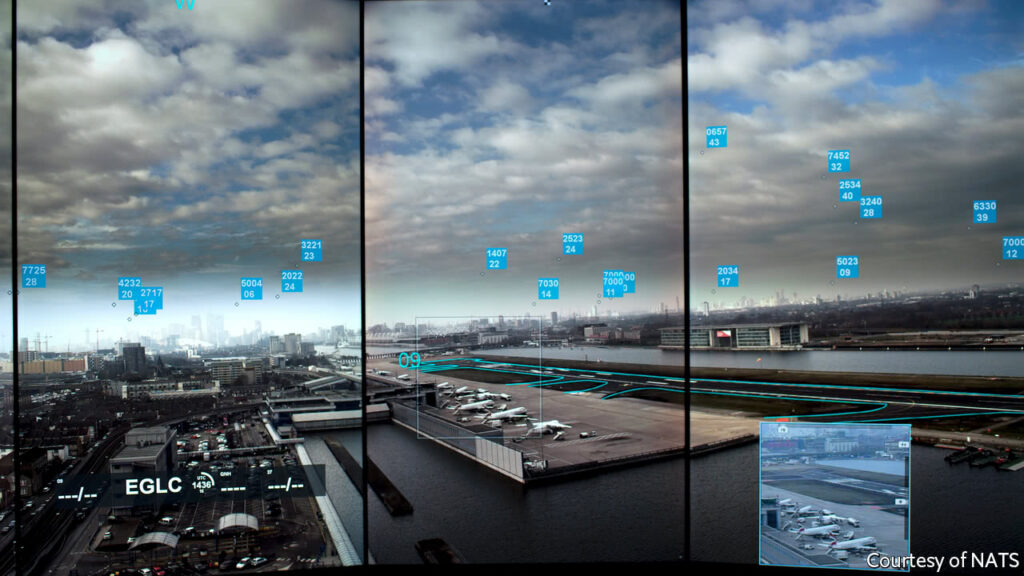

In 2021, LEMH/Menorca airport will no longer have air traffic controllers in their tower. Instead, they will have a network of 360 degree panoramic and pan-tilt zoom cameras which will feed high resolution images to a single, mighty control tower in Bodø, Norway.

Kongsberg (possibly a reference to King Kong who liked climbing up towers, but more likely just named after the town in Norway where it was founded), is working with various airports on a program called Ninox. The plan is to eventually have advanced Remote Tower Systems across 15 different airports.

The plan is to eventually have advanced Remote Tower Systems across 15 different airports. Two systems are already fully operational, and the overall result of the project will be an ATC service that brings “new capabilities to air traffic operations, enabling safe operation at reduced costs.”

They had me at “new capabilities”.

The world’s first air traffic control tower – a wooden hut built in south London 100 years ago.

Is there anybody up there?

Rather than having controllers at the airport, able to look out the window, this system feeds images to a remote control tower. The cameras are incredibly high resolution and can zoom in on the smallest details, detecting movements from birds and drones. They also can have infra-red settings making it possible to see in the dark.

The tools provide greater contingency as well as vision enhancement, and there are options for automated object detection, virtual safety nets, and augmented reality features to be installed.

The real big advantage is that multiple towers can be managed with one all powerful air traffic controller so even the smallest airports providing only AFIS will potentially be able to sign up and have a “controller” over-seeing their traffic – increasing their services without a mega increase in costs.

What if the big ‘what if’ happens

A big “what if?” for this system is “what if the feed fails?”

This isn’t a problem though – each tower is connected to the Remote Towers Centre via networks with huge amounts of redundancy. If one network fails, another can be used to connect again. It also means if one controller gets stuck in traffic, another controller can control from a different spot on the network.

Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your air… craft

So far only Norwegian airports have been set up on the Bodø master network. Røst airport has been operating under remote tower conditions since October 2019, with 3 more coming online through October and November of this year.

But actually…

The concept is already used across Europe, and there are multiple projects around the world.

EDDR/Saarbrücken Airport in Germany has had a remote tower since 2018. With 15,000 flight movements a year it is one of the largest airports to have its operations controlled remotely.

They have projects worldwide including Brazil and New Zealand, and both civilian and military. EGJJ/Jersey Airport in the UK has implemented a contingency system, Iceland is testing the technology for severe weather conditions and LOWW/Vienna is already using their vision enhancement system.

EHAM/Amsterdam Schiphol Airport has also been involved in trials, in conjunction with the Single European Sky ATM Research (SESAR) project and Air Traffic Control the Netherlands (LVNL). The trials tested how controllers would use the cameras, as well as the screens for radar, weather and flight planing which were integrated into their stations, and the results were pretty good.

Grey and cloudy London City Airport looks better from a tower

And then there is AIMEE

AIMEE is an AI developed by the company Searidge, and NATS and NAV Canada are pretty excited about it.

It receives inputs from different sensors, sources and scenarios, and uses an algorithm that learns patterns and so can predict problems, and offer solutions quicker than a human brain can.

AIMEE is being trialled at EGLL/London Heathrow to see if it can improve capacity by as much as 20%. The system will use ground level cameras to monitor aircraft positions in rubbish weather, and will be able to see when aircraft have exited runways much quicker than people eyeballs through fog can.

AIMEE is also being installed at airports like KORD/Chicago O’Hare and CYYC/Calgary where its AI eyeballs will monitor de-icing bays and provide a spacial marshalling system. In KFLL/Fort Lauderdale the system is used on gates for remote apron management.

So the future is remote

People-less control towers are not a thing of the future, they are happening now. Anytime you fly across London, you are probably being controlled by controllers in Swanwick.

For pilots, there is no change in procedures – they will still talk to personnel on the radio, but the actual people looking after you are squirrelled away in their remote tower in Norway.

Bodø Tower – What ATC see

Are we going to have a Matrix type AI computers taking over situation?

No, don’t worry, it won’t.

All this technology is there to supplement real people brains because it can process stuff faster. But it is unable to make the decisions human ATC currently make, so we are more likely to get pilot-less airplanes before we see entirely people-less control towers.

So far they think the rule will remain in place until the end of January next year. Given the current

So far they think the rule will remain in place until the end of January next year. Given the current

Why does aviation hate them?

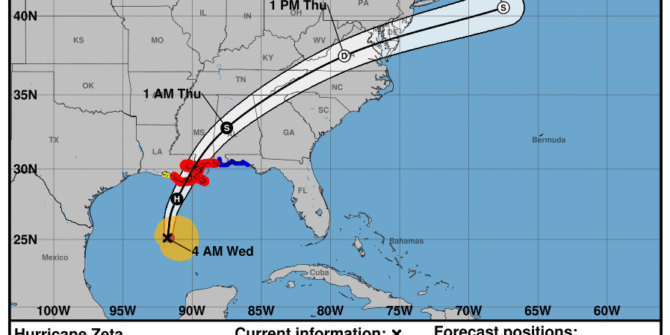

Why does aviation hate them? Satellites monitor storms as well, but mainly just send down horrifying photos of how massive they are.

Satellites monitor storms as well, but mainly just send down horrifying photos of how massive they are.

We got special permission for the crew to stay overnight in PADK, UHPP, RJBB, RPLC and WAPP for crew rest.

We got special permission for the crew to stay overnight in PADK, UHPP, RJBB, RPLC and WAPP for crew rest. There are some good-to-know and some need-to-know points about these parts, so read on…

There are some good-to-know and some need-to-know points about these parts, so read on…