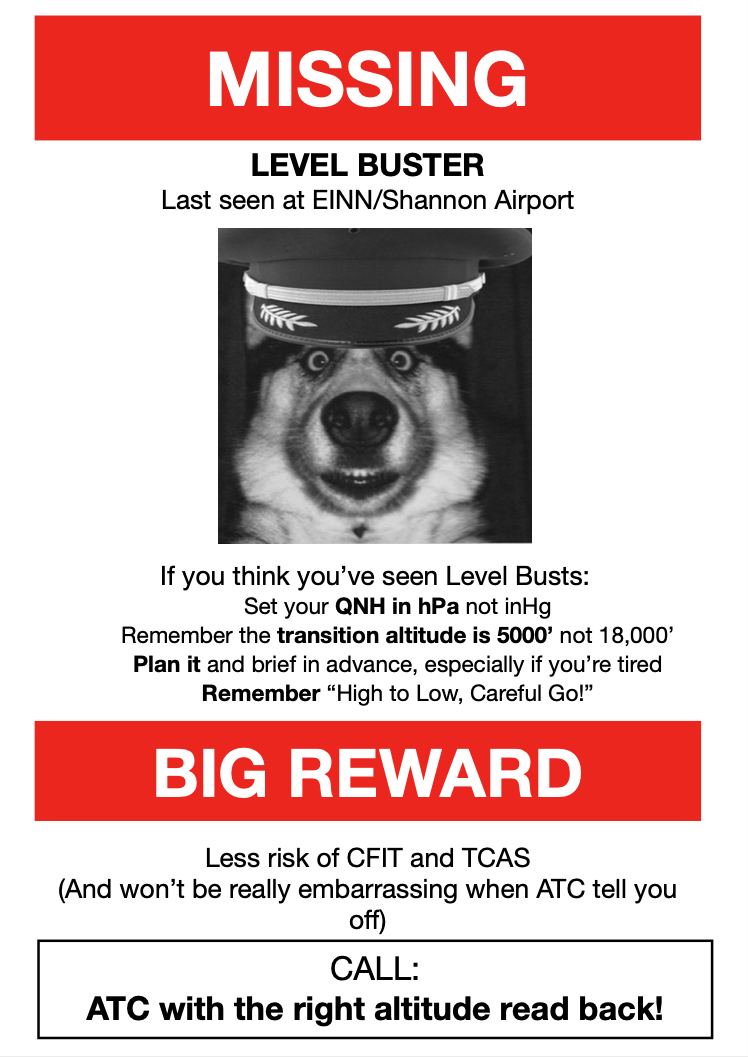

Level busts at EINN/Shannon Airport are a problem. A big problem. Big enough that the IAA have made a presentation on them, alongside the NBAA. Why the NBAA? Well, because a disproportionate number involve North American Business jets.

We’ll start with a little story.

Once upon a time, not so long ago, a pilot called Hank* (*name changed for anonymity) was flying his Business Jet over from the US to Europe, and he decided to stop off at Shannon airport. Shannon is, after all, on the Emerald Coast so it’s very pretty but more importantly its just on the other side of the Atlantic, you can do your US customs stuff there, and they have fuel for your airplane and Guinness for you.

So off Hank heads, and he’s done his homework. He’s planned for the whole NAT HLA bit. Alas, though, he has not planned for the actual landing into Shannon bit. Tired, distracted by the thoughts of Guinness and caught out by a much lower transition altitude, Hank forgets to change his altimeter from inches mercury to hectopascals, and when ATC says “Set QNH 988” what does he do?

He sets 2988inHg…

And so he descends down, aiming to level off at a nice safe altitude. Only his altimeter is over-reading by 720 feet. Hank gets within 2nm and 500ft of some pretty sticky-uppy terrain before ATC spots the errant aircraft and saves the day…

So, Hank was added to a long list of North American Business Jet operators who had a nasty level bust in Shannon and was embarrassed.

The story, differently.

Now, the story really begins…

I am not a North American BizJet operator so it doesn’t apply to me?

Well, it could and it’s useful for anyone to think about really. Level busts are an issue all over, and if you operate into any high traffic density spot (London is a particularly good example) then even the most minor of busting can result in a traffic conflict.

Then there is the risk of CFIT – controlled flight into terrain. Busting downwards in areas with high terrain could lead to this. In fact, most CFITs occur during the approach and landing phase.

300 feet is your limit. Anything beyond that and you’ve got a bust on your hands.

What’s with Shannon and North American BizJet operators?

EINN/Shannon is a US Customs and Border pre-clearance airport, and it is in a handy spot on the west coast of Ireland making it perfect for aircraft with slightly less range to hop between the US and Europe. So it gets a higher number of BizJets from the US. In fact, 30% of their flights are North American BizJets (out of 25,000 or so flights a year).

But despite being only 30% of traffic, they are involved in the majority of level busts. In 2019, 68% of busts in Shannon were, you guessed it, by the NABJ brigade. So far, in 2022, they’ve been responsible for a whopping 100%!

So why does Shannon see so many?

Well, in all fairness, there are some things that make it more complicated if you’re used to flying in the US.

Shannon, like most of Europe, uses hPa instead of inches of mercury, and this can lead to “mis-setting” on the QNH. Like we saw with poor Hank (based on an actual true story) – this is probably the most common cause of level busts in Shannon.

Then there is the transition altitude. Unlike the US and their nice standard always 18,000ft, Shannon uses 5000ft which can lead to a late (or early) change to and from local QNH. Chuck in some weather and particularly non-ISA one and there’s your problem.

And of course, folk heading in from a long North Atlantic night flight might be tired, unfamiliar, or just not planning it very well.

So what can pilots do to avoid level busts?

- Add a mention of the risk into your briefing if you’re heading to Shannon. Or anywhere where level busts are an issue.

- Remember “High to low: careful go!”

- Don’t forget to set QNH in hectopascal and not inches mercury when operating into Europe.

- Check the transition altitude, and plan ahead if it’s a low one.

- Avoid aggressive descents – you can ask ATC for more track miles if you need.

- Read the NBAA/IAA presentation for more info.

More on the topic:

- More: US Pre-Clearance: How does it work?

- More: Liquid Lunch

- More: Covid impact on North Atlantic diversion airports

- More: More NAT half-tracks are coming

- More: Midweek Briefing 01JUN: EASA Updates ‘Suspect Aircraft’ Guidelines, 8th French ATC Strike

More reading:

- Latest: FAA Warns on Runway Length Data and Overrun Risk

- Latest: EASA’s New Cyber and Data Risk Rule for Operators in Europe

- Latest: Airport Spy: Real World Reports from Crews

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly

Rebecca, as a retired controller (Liverpool John Lennon Airport) I remember that the UK phraseology when the QNH was less than 1000 was to add ‘millibars’ – now ‘hectopascals.- to the pressure setting, in order to remind US pilots etc that it was not inches. I assume that still applies. Perhaps Irish ATC, especially Shannon, should adopt this difference from ICAO phraseology?

I am a line check airman who flies into Shannon at least 3 times a month. More importantly, Europe constantly.

First, placing a transition level or transition altitude below 10,000 is pure evil. Let’s take a moment and evaluate what we’ll be doing when we reach those altitudes. The likelihood of missing such an important task is very large. I know you hear me London!

Second, North American operators do not understand the significance of transition level and transition altitude. You need to understand the definition of each.

Lastly, altimeter setting procedures must be specific and adhered to at all times.

Our company policy was to set hPa/InHg as soon as you inbound or outbound of the FIR you flying. So once you eastbound leaving the NY FIR you change to hPa because all the FIRs to the east of NY FIR operate in hPa – same procedure applies to westbound flights.

Also as soon as you are given a decent with an altitude then you change altimeter setting to QNH and x-check altitudes. When climbing and cleared to a FL then altimeters are set to Std 1013 and FLs x-checked. Altitude busts with this procedure was very exceptional.

Your points are mostly well taken, but I’d offer one adjustment, in the interest of “focus on what matters” During arrivals, the Transition Level is the important number to be aware of and brief, not the Transition Altitude. Change from QNE TO QNH when descending through the Transition Level, and change from QNH to QNE when climbing through the transition Altitude. As you mentioned clearly, units of measurement are also important, especially for US operators heavily exposed to IN Hg, and rarely hPA.

One recommendation for North American operators; Put changing to hPa (and vice-versa) on your “Things to do at 30 West” checklist.

Looking forward to Jonathan’s presentation in Austin! We’ve had the London TMA folks over for a similar presentation in the past.

Rebecca, thank you so much for this great spin on my presentation, absolutely delighted to see this message being spread in such an engaging way. We are presenting in the issue again at the NBAA iOC in Austin Texas in February. Really great to get such help in our mission to reduce these level busts, much appreciated.