What does your overnight look like when you are downroute? After you’ve checked in to the hotel, and maybe had a quick nap, what’s on your list of things to pass the time? Maybe you’ll swap your pilot uniform for a tourist t-shirt, head into the city, and explore a little. Perhaps you’ll have arranged a coffee with an old friend or colleague. Or, maybe just hang out at the crew hotel and relax.

Not Kimberly Perkins. There’s something more rewarding to be done.

Through her non-profit organization Aviation for Humanity, Kimberly will be heading to the local school, shelter, or orphanage, to meet the children and present them with backpacks and school supplies. She’s not alone. Having started the mission in 2016, they’ve already helped hundreds of people in places like Ethiopia, Tanzania, Mongolia, Nigeria, and Puerto Rico – and closer to home, in Hawaii – where kids in need in Kona received supplies over several visits.

If you’re like me, aviation has given you a lot – not just a career, but a lifetime of wonder, beauty, excitement, and joy. Aviation is special – that’s why we’re in it. And it’s no secret that we’re going through a tough time right now in the eyes of the public. So, when I see aviation giving back – doing something for the world – it’s important to highlight and bring attention to that. We need more of this.

This is why I want to celebrate and share the work that Kimberly, and the many volunteers, are doing. So, how does it work? Pretty simple:

1. You contact Aviation for Humanity, and tell them where you’re going

2. They will locate an underfunded school or orphanage for you to visit, and arrange for the supplies.

3. You go, and share the story of the journey back with Aviation for Humanity.

Imagine using your trip abroad to make a difference in the world – just one short visit, and you can give an entire school or orphanage much needed supplies.

Running a non-profit isn’t easy, and there’s another way you can help right now. Kimberly needs a volunteer Executive Director – to manage coordination with volunteers, logistics for shelter visits, managing social media, fundraising, writing articles, and other things that move the mission forward. Is that you? Maybe you’ve recently retired and are looking for a way to contribute back to aviation? Maybe you’ve got extra time on your hands, or you know someone that this might be suited to? 2-6 hours a week will get you started.

I love seeing the work that OPSGROUP members are doing individually. As I was ‘wow-ing’ my way through the work that Kimberly does, I found another group member featured on an Aviation for Humanity trip – namely Cheryl Pitzer. Cheryl was on our Member Chat a few weeks ago (#7, see it here in the dashboard).

Cheryl, pictured right, flies the MD-10 “Flying Eye Hospital” for Orbis International – an amazing airplane that is part of the Orbis mission of bringing people together to fight avoidable blindness. On that call, Cheryl told us about the work Orbis does, the challenges of operating the airplane internationally, and the reward of using aviation as an agent for good in the world. This is another incredible cause that you too can get involved in.

Kimberly and Cheryl are true aviation pioneers, not just for the non-profit causes that they work so hard on, but also as pioneering women in aviation. It’s no secret that this beloved industry of ours has a massive imbalance of diversity. The numbers and statistics identify the issue – averaging out the small amounts of data that are actually published on the subject, show that the global percentage is around 5% – that’s both the number of female pilots, and the number of women in top management positions at airlines.

Changing those numbers – attracting more women to aviation – is just part of the issue. What is life like if you are one of the 5%? From an interview that I read in another publication, Kimberly said “As I moved through my flying career, I was never lucky enough to encounter a female manager mentor. As I looked up that corporate ladder, it was a sea of men. Such an environment can be lonely, unwelcoming and intimidating“.

For me, right now, that is something that we can all do something about. What is the environment like at your airline or operation? Could you see how it could be lonely, unwelcoming and intimidating? How can you change that?

Just like the work that’s being done for the non-profits, you can do something to make a difference. That difference grows, it’s exponential. It starts with the realisation that you have the power to make things better for other people, especially if you are in a leadership position. A good place to start is by realising that if you do have the power to make things better, but you don’t, then you’re simply part of the problem.

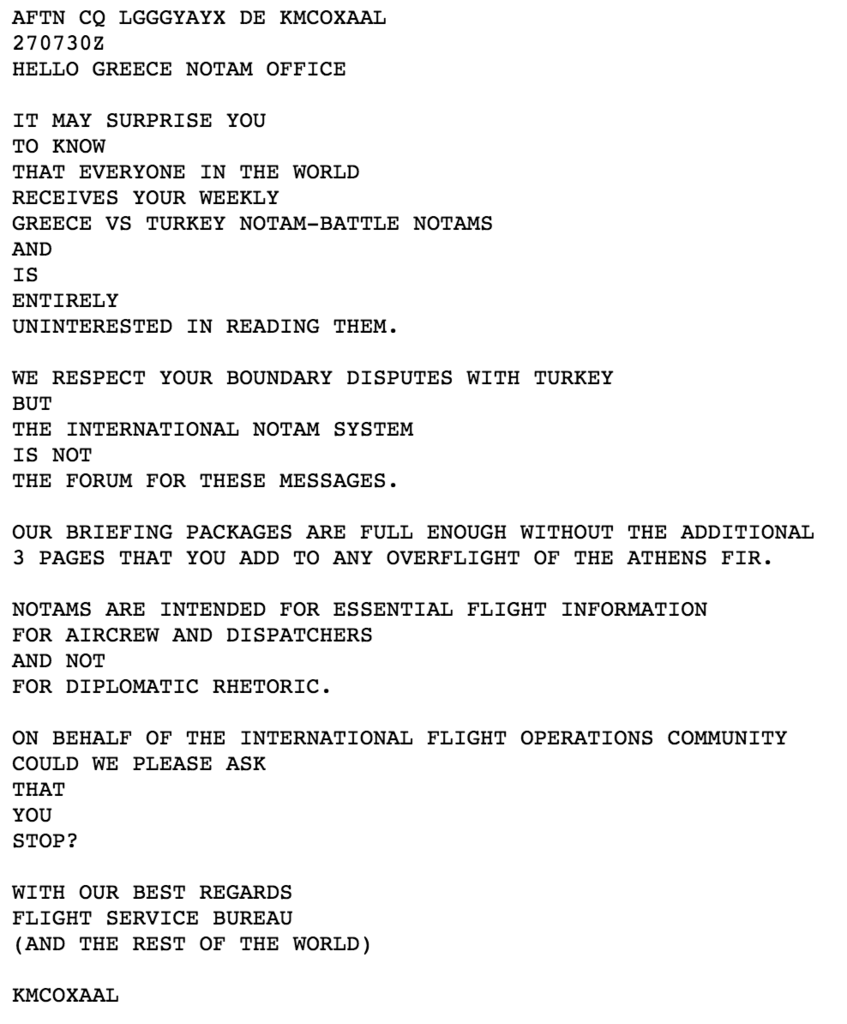

I certainly see some of the inherent aviation gender biases here in OPSGROUP. It’s usually not intentional, nor anything usually deep rooted in opinion – it’s just been built into the system over the last 80 years of how commercial aviation used to work. Sometimes we have group calls that end with someone saying “Thank you Gentlemen”. The very term NOTAM is indicative of the problem – Notice to (air) Men. I like to imagine what it would be like to turn up to work every day and read a flight briefing that is headed “Notice to Women“. I certainly would feel excluded.

You might think that this is subtle, tiny, not important. But the things that create environments that are lonely, unwelcoming and intimidating are usually subtle and unintentional. Only by putting ourselves in the position of others, can we see the full impact.

It’s a process of education that starts with the willingness to see things a little differently, and then making a decision to do something that changes things for the better. Just like Kimberly and Cheryl have done.