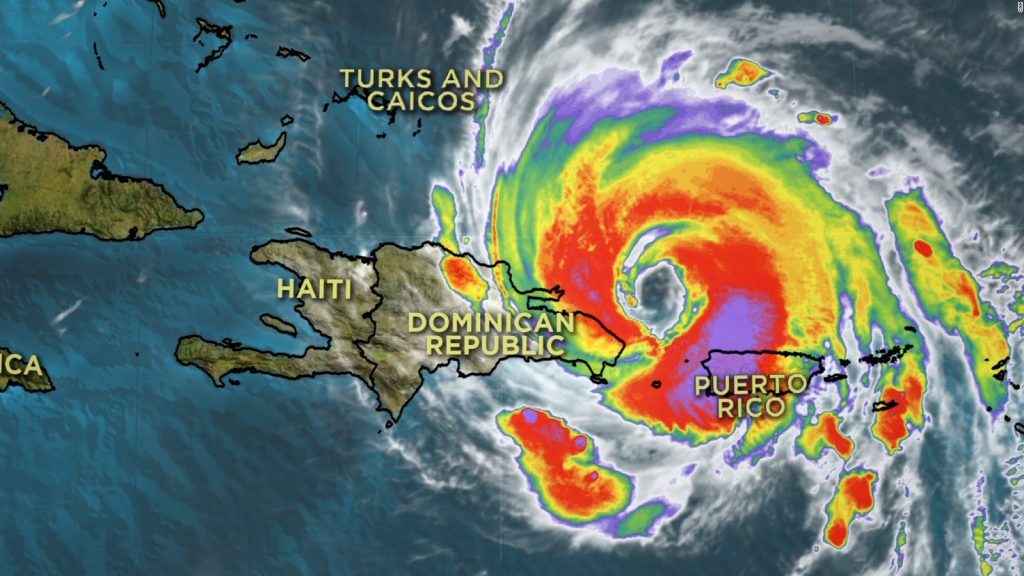

Approximately 200 miles east of Puerto Rico at Flight Level 390, a Miami Center air traffic controller beckoned us on the radio and commanded, “Descend to 17,500 or below and squawk VFR. Good luck.” Hurricane Maria had made land fall over Puerto Rico not even 48 hours prior, and, without power on the island, there were no San Juan Center air traffic controllers to coordinate aircraft flying through their large parcel of airspace.

This was our flight department’s first attempt at delivering humanitarian aid into a natural disaster zone so we expected some unknowns, but this directive was a bit unnerving. We had just begun our trip only hours earlier out of Ft. Lauderdale and now ATC wanted us to fly VFR over the ocean, 200 miles off the coast of our destination? Unknowns are one of many issues flight crews face on a constant basis, but being unprepared is quite another dreaded beast. Were we in over our heads?

A Burgeoning Resource

“Before Hurricane Katrina and the earthquake in Haiti, it was rare for Part 91 and 135 operators to partake in disaster relief,” explained Robin Eissler, the founder of PALS, Patient Airlift Services. “The past 14 years have seen so much change.”

When Katrina struck, Eissler began working with other flight department managers and dispatchers through the NBAA’s Airmail system to figure out a way to coordinate a general aviation response to the disaster. This would eventually become the building blocks for the HERO (Humanitarian Emergency Response Operator) Database, the NBAA’s registry for flight departments seeking to assist in such emergencies. “In terms of our HERO Database, we help to connect the aviation resource (airplane or other individual volunteer) with the relief organization best able to utilize that asset,” said Douglas Carr, Vice President, Regulatory and International Affairs of the NBAA. “Business aircraft can fly on short notice into airfields in which many airliners and cargo planes cannot.” The HERO program works closely with many humanitarian groups, especially Eissler’s PALS.

Shortly after Eissler formed PALS, the earthquake in Haiti struck. She described the general aviation humanitarian response as the grand experiment, “The government response was limited initially. The airlines shut down, and, other than military aircraft, corporate aircraft became a major source of delivering aid. We had over 1,000 flights for food and medical supply drops as well to evacuate the injured.”

In those early trials of PALS and the HERO Database, social media was a major asset. “We had a 13-year old girl in Haiti hit by a bus just after the earthquake and doctors said she needed an immediate evac,” recalled Eissler. “There were strict slots to get into Port Au Prince, and we had a G5 in Connecticut set to depart to get her when it had an engine issue. We immediately posted a need for help on our registry but also on Facebook. Five minutes later a Pilatus pilot just getting ready to leave Haiti posted that he had some room on the aircraft for her. She was delivered to the plane in critical condition laying in the bed of a pickup truck. But she’s alive and well today. Many might think social media is silly, but it can save lives.”

Now that the registries have been tested through further natural disasters, pilots and dispatchers can easily log-in and quickly see what requests have been posted and what missions might match their departments’ capabilities.

Haiti also played a major role in the creation of LIFT, a not-for-profit logistics provider for other NGO’s. It’s founder, Michael Rettig, spent over 30 years in the freight forwarding business. As he assisted in Haiti’s humanitarian response he saw what potential general aviation aircraft had to offer to such a response but also witnessed the lack of organization and preparation.

Rettig thrives on the efficiency of the supply chain and now applies his logistics experience to disaster relief through his organization. “60%-80% of every dollar spent on humanitarian aid used to be spent on logistics. That was way too inefficient,” he explained. “There’s a need for general aviation in humanitarian relief but there was a lack of coordination.”

Large transportation companies like UPS, FedEx and Maersk formed LET’s, Logistics Emergency Teams, to coordinate disaster relief. But general aviation was lacking such coordination. FEMA’s National Response Coordination Center was willing to listen to GA advocates but there needed to be more preemptive coordination. “Too many general aviation aircraft were showing up with aid that wasn’t necessarily what was needed,” Rettig said. “Flying in a G5 filled with Fiji water is a waste of money and resources. I much rather see medications like insulin or advanced communication system components and specialized technicians that can set them up being flown in. Corporate aircraft plug into the overall response framework by delivering high value, high impact aid.” Rettig and Eissler are very familiar with each other as their organizations work hand in hand during these responses. The required aid – whether it be medical or tech oriented – can be flown in and then medical patients can be flown out.

Planning Ahead

As we flew through the Wild West of uncontrolled airspace towards Puerto Rico, talking over a common radio frequency to the aircraft both ahead of and behind us as we obsessively monitored their positions on our Traffic Collision Avoidance System, we finally entered the traffic pattern over a small satellite airport in San Juan. After landing, we tried to maneuver down a taxiway with overturned Cessnas, mangled helicopters, obliterated hangars and even a pit bull limping down the tarmac. This was definitely unexpected.

Thankfully we had one of our maintenance technicians along with us who go out of the plane and guided us safely around the strewn debris. Surface conditions of the airfield are of a primary concern when entering a disaster zone, and without power and phone communications, there may not be much information available. Having a dedicated operator on the ground is so much more helpful in determining the safety of an airfield than putting all your trust in an email from an FBO employee or a flyover to check for debris.

Zac Clancy is Vice President of Global DIRT (Disaster Immediate Response Team), a nonprofit organization made up of prior military personnel who immediately arrive in disaster zones and even pre-position themselves in areas prior to a hurricane’s arrival. “We have multiple responsibilities from restoring communication connectivity to securing and transporting aid.” Once aircraft drop off the aid, what exactly happens to it? “We’ve seen cargo planes drop off tons of humanitarian aid on the tarmac and then leave. No one takes responsibility for it, no one protects it. We unload it, take legal responsibility for it and then work with other NGO’s to deliver it,” Clancy explained. Global DIRT employees also work directly with airport tower controllers in these affected areas on getting ATC slots and clearances for GA operators. “It’s interesting, in many cases I simply walk up to the control tower, knock on the door and speak directly with the controller,” said Clancy.

“We’ll assist you once you get here, but I highly suggest that all operators have a plan in place prior to any type of natural disaster response,” said Clancy.

As we unloaded boxes upon boxes of aid in the blistering afternoon air, we started to reexamine our original “plan”. Our dispatcher had worked tirelessly without rest since the hurricane hit to organize the flights as this type of mission was new to all of us, and she was learning on the go. “It’s the little things you don’t think of that you need to have already planned for. What are you willing and not willing to pack on the airplane? What company personnel should be permitted to go? Even, what type of packaging should be used?! Misunderstandings and miscommunications like these cause delays and headaches,” she explained. “What an aircraft owner or a corporation’s executive team may assume is possible, may not be so. Prior understanding is a key. And their understanding of the risks involved are necessary as well.” Eissler agreed, saying, “Corporate flight departments can get nervous once you start talking about safety and security and all the logistics on the ground. Working with us offers that extra layer of liability protection.” Rettig added – “If I can advise one thing, it’s to partner with a vetted organization that deals with these things. Don’t show up unannounced. No one wants disaster tourism.”

As we prepped our aircraft for departure, the skies over the small executive airport began to get congested with business jets transporting their own aid. A few go-arounds occurred and some aircraft exited the traffic pattern to manoeuvre back around to re-enter. Clear and detailed communications between flight crews were essential for safety.

As for communications on the ground, we were thankful to have a satellite phone to speak to our point of contact in the city that was delivering the aid by truck. ETA updates were necessary as NOTAM’s spelled out that all aircraft must depart the island by sundown or be stuck overnight. Thankfully, our maintenance technician had just finished dealing with an issue with our ELT as we didn’t even want to even consider the possibility of getting stuck overnight.

As we taxied to depart from our first disaster aid drop we were somewhat disappointed. We had planned on making two drops that day but delays in ATC letting us depart Ft. Lauderdale as well as delays in the actual delivering of the aid took much longer than we expected and there would be no way to make another round trip before nightfall. There was also a sense of guilt at having empty seats in the aircraft as we flew back to the mainland. Clancy couldn’t iterate enough, “The return legs of the relief flights are often under-utilized. While there is the need for aid coming in, often times there’s a need for things to go out as well: people highly in need of medical care, stranded citizens, and returning aid workers. Unfortunately, these flights back are empty because the planning wasn’t in place to know of such need.” In our situation, that would be the last time we would fly back with an empty aircraft.

Coordination

At the hotel that night, I began posting on OpsGroup about what we had witnessed, what we had learned, and what some of our concerns and misunderstandings were. The response was relieving as other operators and OpsGroup personnel chimed in with much needed info and support for the continuing flights.

Our dispatcher took her job to the next strata, and, in the ensuing days, we had much more structured missions. She coordinated with LIFT to send our own company’s disaster relief aid over in a cargo plane; no more strategic packing of goods in our corporate jet and no leaving behind of aid that was too big to fit in our plane. Whatever we needed to get over to the island could go. In exchange, Rettig coordinated a flight in which we flew technicians from a large tech company into a decommissioned naval airfield to begin fixing a specialized communication system to bring back cell coverage across the island.

There were no instrument approaches, just a government issued airport diagram. But a surprise radio contact from a Marine Corps air traffic controller aligned with a battalion sheltering in one of the decrepit hangars offered much appreciated assistance. Once again, the unexpected! As the technicians and engineers worked through the day, we could sense that this mission, which our aircraft was well suited for, may offer much more to the overall disaster response than the general aid we had delivered the day before.

The following day we flew in security and NGO personnel set up by ALANAid, American Logistics Aid Network, which works closely with LIFT, into San Juan International Airport, by then fully operational. Upon return, PALS filled the aircraft with sick and elderly personnel.

Again, we were a bit weary of what to expect as far as handling those in medical need. “As for planning, a flight department should know how they want to deal with the sick and elderly,” said Eissler. “We have you covered liability-wise, but departments have some small decisions to make beforehand – like, if they want passengers sitting up or laying down. What food, drink or medications you may want onboard. Many people don’t think of these things prior to picking up these passengers. But we point them in the right direction.”

Again, we were a bit weary of what to expect as far as handling those in medical need. “As for planning, a flight department should know how they want to deal with the sick and elderly,” said Eissler. “We have you covered liability-wise, but departments have some small decisions to make beforehand – like, if they want passengers sitting up or laying down. What food, drink or medications you may want onboard. Many people don’t think of these things prior to picking up these passengers. But we point them in the right direction.”

Once we met our passengers, though, all weariness evaporated. Just witnessing their appreciation for simply taking them out of the sweltering FBO and into our aircraft’s air conditioning was heartwarming. And that would pale in comparison to witnessing them being reunited with family on the mainland.

The response in Puerto Rico made clear that there are a number of organizations that can assist a flight department in delivering disaster relief. Yet it seems to be a very small circle. They all seem to know each

other, work with each other… and, more importantly, respect each other.

It makes sense, considering the reason many of these people do this type of purposeful work. Before Katrina, Eissler was overseeing an aircraft management company. A few years later after creating PALS, she would be getting calls from the military. “I’ve ordered an Air National Guard commander where to send his aircraft while standing in my kitchen on the phone. I’ve yelled at a commander for landing his C130’s on a runway that couldn’t support its weight. I’ve called in for a King Air to fly over a runway to check its integrity for other aircraft. And here I am – a mom in Texas and I’m making these calls!”

Rettig took a similar path; before Haiti he was working for a large shipping corporation but after coordinating a small aid flight in a friend’s PC12 to Haiti he found a passion. Now he’s handling transportation in all forms and sizes to assist NGO’s with humanitarian aid logistics across the globe. That passion underlies how many of these organizations can help general aviation departments in their effort to deliver humanitarian aid.

We continued flying into Puerto Rico for a few more days. Each day the mission changed but the logistics of the flights got easier as basic services began coming back on line. On our last flight back to the mainland to drop off passengers in Ft. Lauderdale, I walked an elderly woman with kidney failure into the FBO. After her awaiting family celebrated her arrival she hugged me with a tear smeared face. She then proceeded to FaceTime with her niece, an unmarried nurse in NYC. While holding me in the in frame of the phone’s video feed, she asked if I was married and if I’d like to meet her niece. More of the unexpected! Her hearty laugh was a great ending note on what was such a meaningful – and adrenaline filled – week of flying.

That year we would respond to hurricane aftermaths in Texas, Florida and North Carolina. And though we hope for no more natural disasters, we know better. And we look forward to helping in any way we can when they do happen. In normal operations we focus on service to ensure safe and successful business operations, the importance of which cannot be overstated. But when disaster relief becomes the business at hand, one cannot help to feel an even greater sense of purpose. Though achieving that goal can be daunting and anxiety-ridden, there are dedicated people out there to help in succeeding in that mission. And all who take part just may find enjoyment in the experience, even in the unexpected.

Resources

- NBAA Humanitarian Emergency Response Operator (HERO) Database

- Patient Airlift Services

- LIFT

- ALANaid

- Global Disaster Immediate Response Team

More on the topic:

- More: Hurricane Beryl

- More: Haiti Crisis: Airport Attacked, Aircraft Shot

- More: Hurricane Idalia: Florida Airport Closures – 1200z Aug 30

- More: Hurricane Season Approaching: What’s in store for 2023?

- More: Hurricane Freddy: Still going strong

More reading:

- Latest: Teterboro: RIP the RUUDY SIX

- Latest: 400% increase in GPS Spoofing; Workgroup established

- Latest: GPS Spoofing WorkGroup 2024

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly