How often do you think about who you have down the back? The recent Belarus incident might be prompting you to think a little more about who you have onboard and whether there are any political or operational considerations their presence might lead to.

So, here are some things to think about – from the political considerations of country politics, to what to do if the troublemaking is taking place onboard.

The Politics.

It would nice to stay above this, but unfortunately even at 40,000 feet we seem unable to escape the (often messy) world of politics, which means some consideration of who you have onboard, where your aircraft is registered, and where you are heading to and from, should form part of your overall risk assessment.

Israel is a fairly obvious example. They have a long history of strained relationships with neighbouring countries. It was only in 2020 that several of their closest neighbours renewed ties with Israel and allowed operations and overflights to re-start.

This has not happened with all their neighbours though. If you are routing to or from Lebanon then LLBG/Tel Aviv is unlikely to accept you in a diversion. Likewise, if you divert to OLBA/Beirut with Israeli passengers onboard, this could pose some serious issues for them. Checking Country Rules and Restrictions for notes on Israeli flights (originating from or routing to) will bring up a fair few places that you need to be aware of – such as Pakistan – who still will not accept overflights or diversions to aircraft coming from, going to, or registered in Israel.

Israel itself is allowing aircraft in, but read the small print on this because in order to land in Israel you must be departing from one of their approved airports, and your crew and passengers must be nationals of countries that have diplomatic relations with Israel.

A major improvement in relationships between Saudi Arabia and Israel

India/Pakistan have an ongoing feud that has led to huge fence being erected along much of their border. The countries allow over flights from each other, but if you are operating into one, a diversion to the other may cause some consternation. OPLA/Lahore in particular is one to look out for because of its proximity to the Indian border.

If you divert into India with a technical issue that sees you grounded, and you are carrying Pakistani passengers there may be issues with them overnighting in the country.

The border fence is an impressive ‘monument’ to conflict

It isn’t always political though.

Sometimes the folk causing problems are the troublemakers onboard.

If you can spot them before takeoff then all the better. Cabin Crew are your last line of defense for ensuring anyone under the influence of alcohol (or just being generally offensive) is offloaded before they have a chance to cause issues. Remember, the law is on your side here – most countries specify that it is a criminal offense to be drunk onboard an aircraft.

The FAA have just made it a whole lot easier to handle disruptive passengers. In January 2021 they announced a zero tolerance policy for bad behavior, and they have a hefty 57 different civil penalty actions available to them. So far for 2021, they have received around 3,100 reports of unruliness and these have led to open investigations for 465 incidents – a sizable increase on the 146 seen in 2019.

What counts as disruptive?

Anything that is disrupting the flight, causing a nuisance to other passengers, or impacting the safety onboard really.

- Being intoxicated with drugs or alcohol

- Refusing security checks

- Disobeying instructions

- Threatening, abusive or insulting words

ICAO put out a list of the top reasons for unruliness and unsurprisingly, alcohol topped it, with compliance with regulations (smoking, seatbelt signs etc) not far behind. In the top 16 there were also pet/emotional support animal related reasons, along with seat reclining disputes.

What actions do you have available onboard?

A PA from the Captain telling all the other passengers that “The Annoying Person in Seat 45B is going to delay everyones’ holidays unless they sit down!” might do the trick for passengers who are just a bit of a nuisance (although your company might frown on this). But for those passengers that are posing an actual danger, the Tokyo Convention is your go-to convention here.

First written in 1963, it focuses on security and lays out what the rules and rights are.

The convention gives any passenger the right to take “reasonable preventative measures” to maintain their own safety (without having to ask permission first), but also makes it pretty clear that only the Captain has the right to order a passenger be restrained, and this requires some thought because it does need to be justified – a “high burden of proof” will be needed.

And justified means it really is the only remaining option available to prevent the person from endangering the safety of themself, passengers, crew or the aircraft. What you deem “endangering safety” is up to you but bear in mind there will be a bunch of witnesses on board.

Following on from Tokyo came the 1970 Hague hijacking definition and then the 1971 Montreal convention that deals with sabotage, and the criminalization of anything being brought onboard to jeopardize safety. In 1974 they revisited the good old Chicago convention and aviation security standards were developed. History lesson over, but it is worth having a vague understanding on what these contain in case you ever need to call on one.

Cellphones mean a lot of witnesses…

Aside from these there always remains the option to divert.

In 2015, a flight from Las Vegas to Germany was forced to divert after a passenger became unruly over a cat. The woman had managed to board with the cat in her purse, rather than an official carrier, leading crew to storing the offending feline in a bathroom. This upset the lady and she threatened to “bring the aircraft” down if her pet was not released from its prison. Purr-ison if you like.

Diversions due unruly passengers are alarming not uncommon because while a passenger can be restrained, the implications of doing so for a substantially long flight need to be considered, as does the ongoing stress for other passengers onboard.

The UK CAA suggest that a diversion typically costs from around £10,000 – £80,000 depending on aircraft size.

Back on the ground

OK, so you’ve called the cops. Before they get there you might want to do a PA ensuring the other passengers know to remain in their seats and not get in the way of the police or that bad passenger might just slip out with the rest of the herd. But when they are arrested, who actually has the right to prosecute?

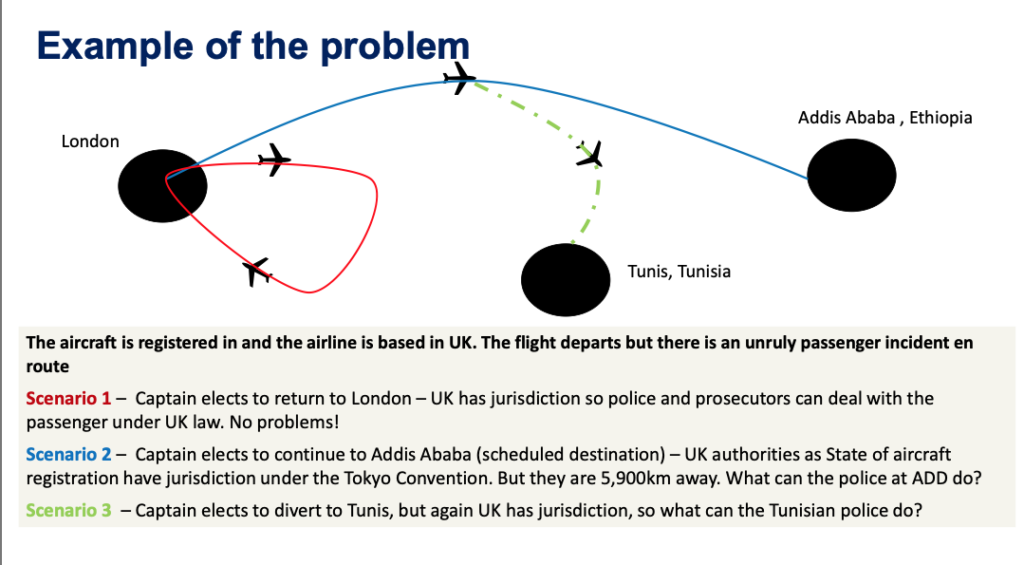

The Tokyo Convention give explicit jurisdiction rights to the airline’s country of registration when it comes to court. However, there are some doors left open there for other countries to seek extradition as well. These were brought in following a case in 1949 where a passenger sunk their teeth into the ear of the pilot. Alas, the US had no laws at that time which could apply to crimes committed while flying over an ocean, so the biter went free.

In 2014, the Montreal Protocol was also issued. This extends automatic jurisdiction over the crime to the destination. Important because it stops criminals sneaking off free because they were clever enough to commit the crime while heading into a country that the airplane was not registered in.

This rather ugly slide by ICAO gives an ‘Example of the problem’.

This was made in 2016 so no excuses for the lack of decent Powerpoint skills

So, for now, the crime is punishable by the country of registration, but the Montreal Protocol sort of extends the right of police in destination country to basically help in arresting the passenger.

In-ads/ Prisoners

An inadmissible passengers is not a prisoner.

Generally, it is some poor person who forgot to get a visa in their passport and have been turned away at destination. Usually it is on the carrier that brought them in (and didn’t check them at the departure airport properly) to take them home again, and as the Captain, you can expect to be handed the documents and passport for the in-ad at departure. However, you cannot detain an in-ad onboard when you land back wherever you are going. So alert the authorities and make sure they are there to meet the passenger. If not, you pretty much have to let them go.

Prisoners will always be escorted. For any “unusual” passenger, it is best to board them first and disembark them last. They must not seated at an emergency exit and preferably should be near the back of the aircraft and away from the aisle.

Emotional Support Animals

The rules for these recently changed and no more bizarre creatures have to be accepted. The UK do not allow any animals that are not service animals with full documentation. The US is the same, and only classify dogs as bone-afide service animals.

Cool sweater. But still not allowed onboard.

So, have a think about who is down the back.

Having an awareness of the nationalities of your passengers and considerations as to the countries you are overflying and their political relationships with other countries can be useful.

Knowing what the Tokyo Convention does and does not allow you to do with unruly passengers is also a good one to read up on. Your power as Captain only really extends to when the doors open.

If want to read more on unruly passengers then IATA put out some handy info here.

If it’s the Tokyo Convention then ICAO have it published here (although it makes for some dull legal reading).

And if you’d like to read about the emotional support pet rulings (for the US) then here you are.

IFALPA have a very useful paper on carrying in-ad, deportee and other non-revenue passengers.

Article photo courtesy @surachetsh.

More on the topic:

- More: Belarus: Politics, Piracy or Airspace Risk?

- More: Belarus: A closer look at their aviation industry

- More: Do you use Bermuda (TXKF) as a NAT alternate at night?

- More: Midweek Briefing 29JUN: Santa Maria Oceanic Strike, US Entry Requirements

- More: Midweek Briefing 22JUN: Iceland ATC strike – end in sight, Israel FPL changes

More reading:

- Latest: Teterboro: RIP the RUUDY SIX

- Latest: 400% increase in GPS Spoofing; Workgroup established

- Latest: GPS Spoofing WorkGroup 2024

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly