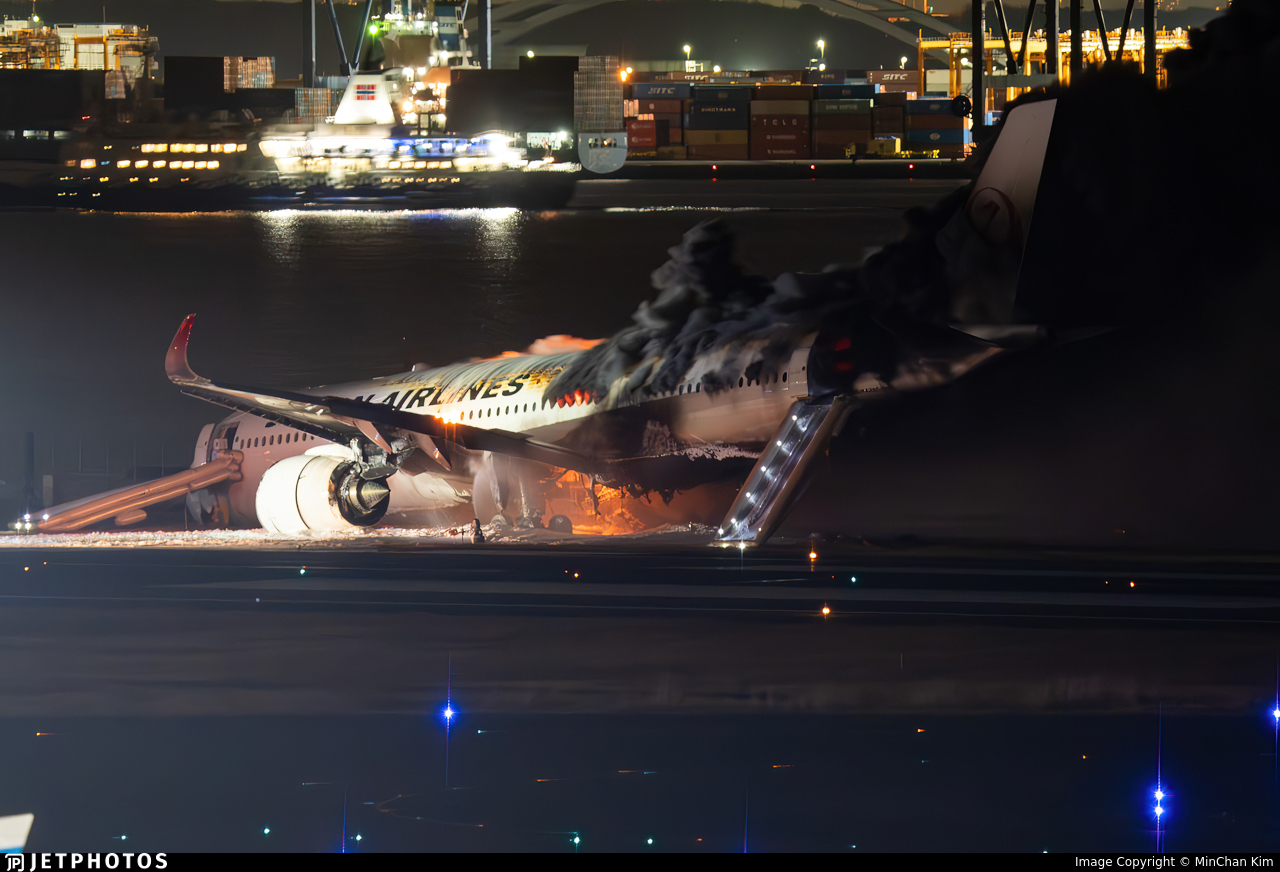

Japan has announced changes (in Japanese) to ATC protocols at airports throughout the country. This follows the tragic collision of an Airbus A350 and Dash 8 on an active runway at RJTT/Haneda on Jan 2.

While we wait for more answers, authorities have been quick to implement new procedures. Here’s what you need to know (translated), if you’re headed to Japan tomorrow.

Visually Clear

Authorities are urging operators to mandate a check by aircrew that the runway is visually clear before landing or entering. In other words – don’t rely on a clearance alone.

You may need to take this one with a grain of salt. For a myriad of reasons, it may not be practical or possible for pilots to make an accurate assessment that a runway is vacant. Take the example below – how would you fare?

Cleared for immediate take-off, with one landing behind. Is the runway clear, or is that a vehicle ahead?

But from an airmanship perspective, the intention is that our eyeballs may become the last line of defense.

Forget your place in the queue

Early indications from the accident transcript indicate that the crew of the Dash 8 may have misinterpreted the use of the phrase ‘number 1’ when cleared to the runway’s holding point.

To a fluent English speaker, the implication may appear quite simple – you are number one in the queue to depart.

But to the crew of the Dash, it may have meant you are number one for the runway.

So, from now on ATC will no longer advise aircraft of their place in the sequence for departure.

Their official note says there are now only four phrases that will be used to imply an aircraft can enter a runway. These are:

- Cleared for take-off.

- Line up and wait.

- Cross runway.

- Taxi via runway.

If you hear anything else, it is non-standard. Stop and make sure you clarify the clearance.

Behind the Scenes

There are changes happening in the tower too. While they have no operational impact for pilots, it may be reassuring to know about them.

Essentially the bulletin reinforces there will be more staff on hand to constantly monitor ground radar for early detection of potential runway incursions.

And work is underway to improve the visibility of paint and signage at runway holding points, especially where no stop-bars are installed or working.

As a collective, the industry needs to do more

Can I address an elephant in the room?

Having read the above bulletin, I find myself flipping the page over to see what’s on the other side. I can’t help but ask myself… is that it?

Japan’s bulletin is, for all intents and purposes a reminder of what should be happening anyway.

In my opinion, it seems to offer little more than a gesture of reassurance that authorities have been seen to act in the face of another tragedy.

The reality is that this wasn’t just a Japan problem. All the warning signs were there before Haneda, around the world.

Have you seen this report? Back in November it was assembled by a team of specialists who cast doubt over the future safety of the US NAS.

In a six-week period, there had been no less than five near-miss incidents involving runway incursions and passenger jets at major US airports. Five, in six weeks – the highest rate in over half a decade.

In the report they identified risk factors (such as staff shortages, aging infrastructure and inconsistent funding) as issues endemic to these near-misses. No amount of bulletin-writing can fix these problems.

With the news that traffic levels will soon surpass those seen before the pandemic, I feel unsettled that the bullish outlook for global aviation is quickly outgrowing the safety infrastructure that protects us.

Perhaps it’s time for us to collectively tap the brakes and put safety ahead of profit, lest Haneda be the first of a number of lessons.

As a parting shot, it’s important to note that technologies already exist to solidly improve runway safety far beyond bulletins like the one above. Take for instance, the final approach runway occupancy signal (FAROS).

This independent and fully automatic safety addition to runway status lights warn pilots on final approach in real time that a runway is occupied. Consider the impact this may have had that evening in the darkness of Haneda’s Runway 34R.

What’s needed is the time, money and willingness of industry stakeholders to implement them. We need to do more to prevent accidents like Haneda, rather than react to them. At the very least, Haneda is a wake-up call that the time to act on truly preventing runway incursions at busy airports is now, and not next time.

More on the topic:

- More: Japan Reopens: Crew & Passenger Entry Rules Explained

- More: Japanese Prime Minster Funeral: Tokyo Restrictions

- More: Declassified: New Crew Rules in Japan

- More: South East Asia: Open for Business

- More: Tokyo airports set to ban GA/BA ops for a week

More reading:

- Latest: OPSGROUP is hiring! Wanted: Junior International Ops Specialist

- Latest: LOA Guide for US Operators

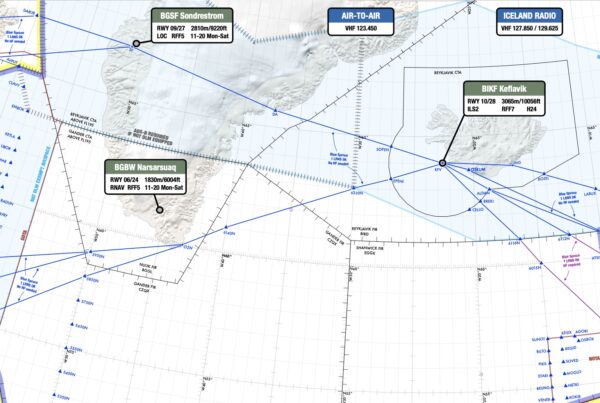

- Latest: NAT Ops: Flying the Blue Spruce Routes

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly

Hi Chris,

Good points you bring up. I think there IS more all crews can do from a Human Factors point of view. While technology is great, there have been recent incidents (American and Delta at JFK) where the technology SHOULD have intervened, but for various reasons, didn’t prevent the incursion.

The Japanese, have, in one significant instance in the past, introduced what many think is a simple, “how could this be effective” cross-checking technique. I am talking about the altitude setting procedure of BOTH pilots pointing at the altitude selector while verifying the assigned altitude. Known as shisa kanko, it is associating one’s tasks with physical movements and vocalizations. When a train driver verifies a speed, they point and vocalize, even if they are alone.

I believe crews taking a more deliberate look, maybe point and call-out could be effective. We already, before taking the runway, look both ways, and the respective pilot calls out that either the final or the runway is clear. We don’t point, but maybe we should. We tend to take the fact that the runway is clear on landing for granted, once “cleared to land”. Maybe the PM should, at some point of final, point at the runway and verbalize that the runway is clear. Obviously this couldn’t be done on a to-minimums instrument approach, but VFR conditions (at night) seems to be where these have taken place.

Until the technologies can be deployed, be more deliberate, use a physical motion and BOTH agree on what is seen. Simple stuff!

Steve

Here is a link to an article on the Japanese technique of pointing and calling.

http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/pointing-and-calling-japan-trains

Really interesting Steve, thanks for sharing this.