- July 2017: First launches of ICBM’s from North Korea

- Western portion of Japanese airspace is a new risk area

- New OPSGROUP guidance to Members, Note 30: Japanese Missile risk

The North Korean game has changed. Even if aircraft operators stopped flying through the Pyongyang FIR last year, nobody really thought there was much of a tangible risk. The chances of a missile actually hitting an aircraft seemed slim, and any discussion on the subject didn’t last long.

Things look different now. In July, the DPRK tested two Hwasong-14 Intercontinental missiles (the July 4th one is above), the first ICBM’s successfully launched from North Korea. ICBM’s are larger, and fly further, than the other missiles we’ve previously seen. Both of these landed in the Sea of Japan, well inside the Fukuoka Flight Information Region (Japanese airspace), and significantly, at least one did not re-enter the atmosphere intact – meaning that a debris field of missile fragments passed through the airspace, not just one complete missile.

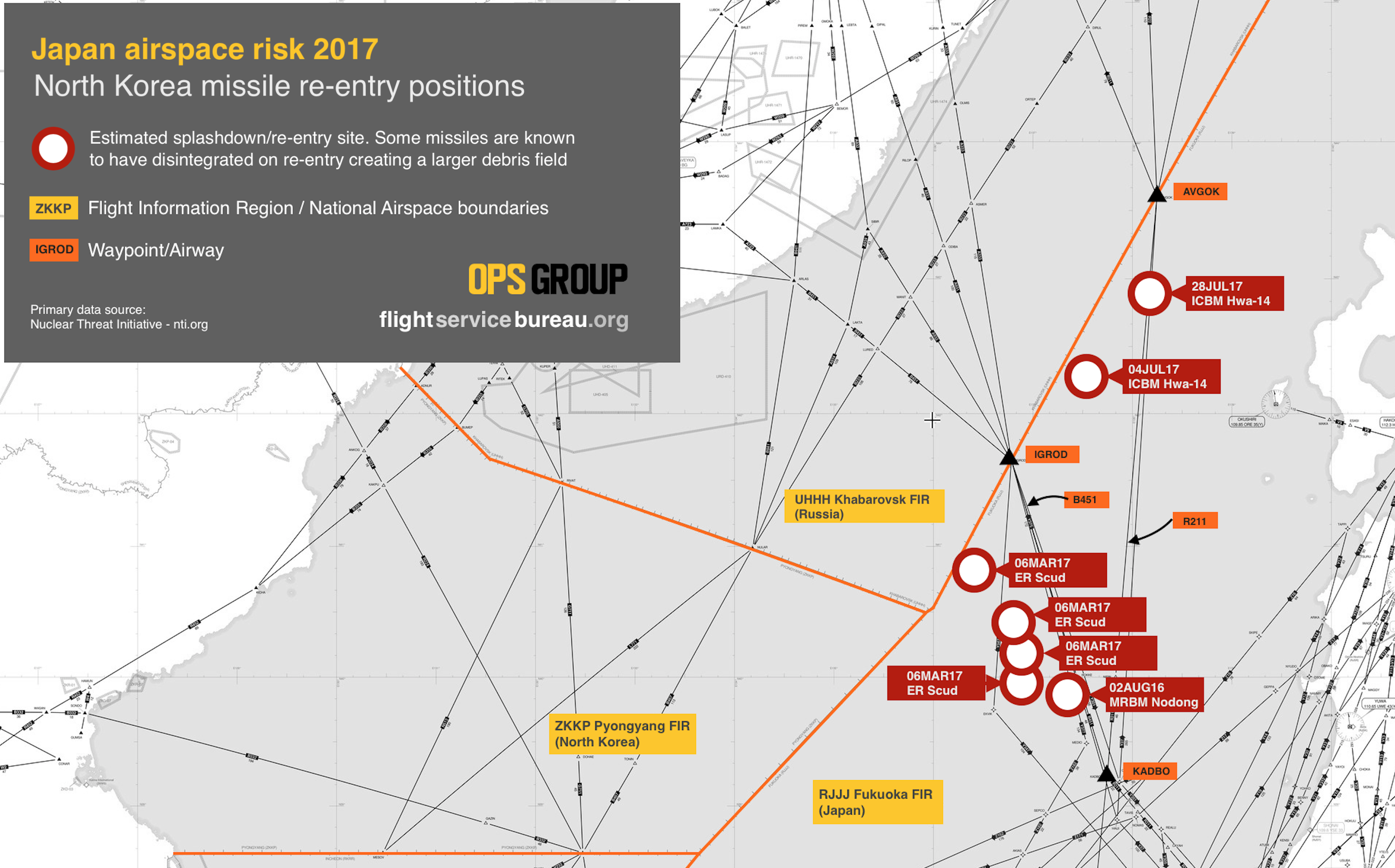

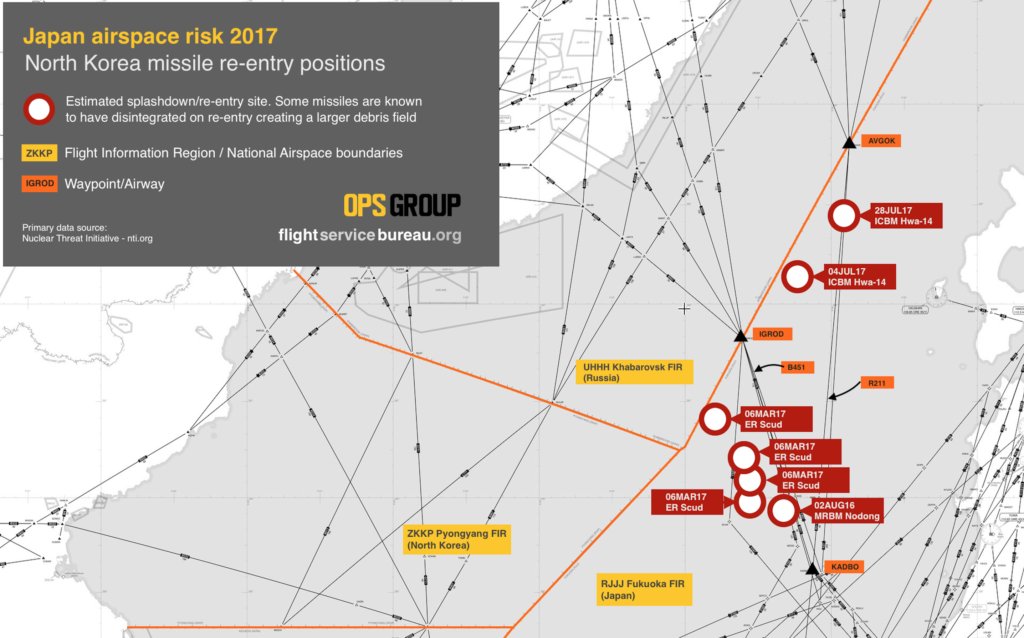

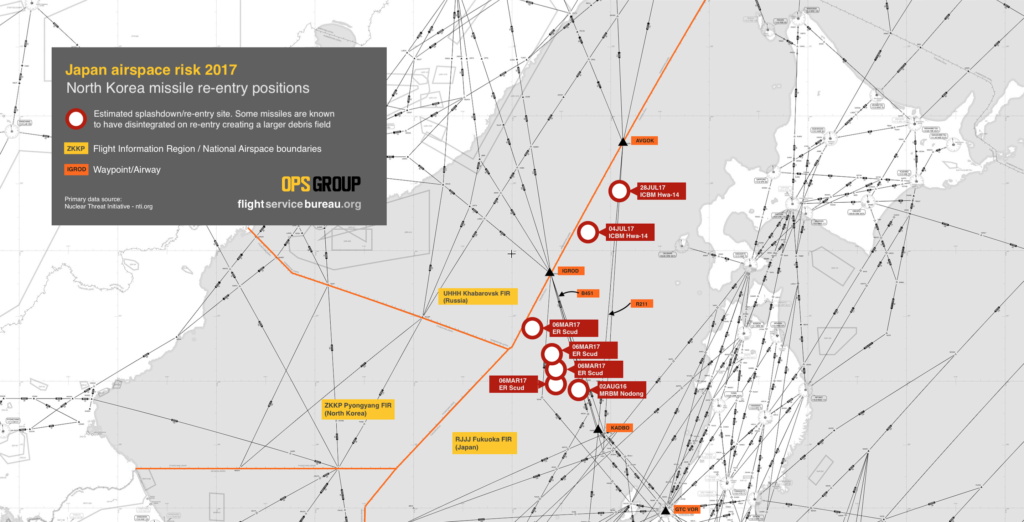

We drew a map, with our best estimates of the landing positions of all launches in the last year that ended in Japanese airspace. The results are quite clear:

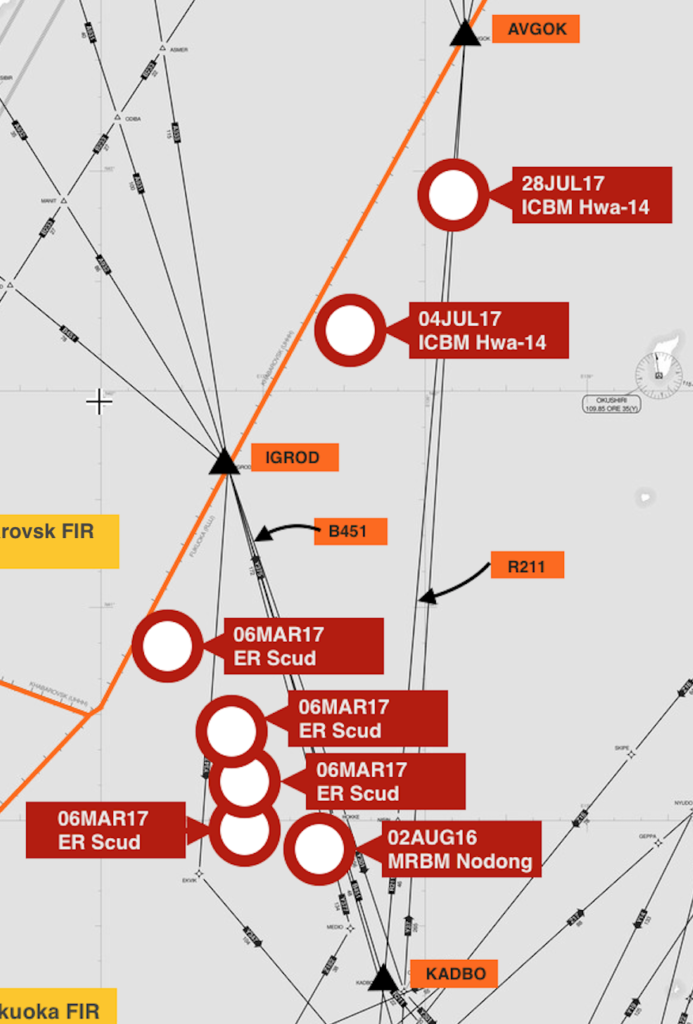

Zooming in even further, we can see each of the estimated landing sites. It is important to note that the landing positions vary in the degree of accuracy with which it is possible to estimate them. The highest accuracy is for the 28JUL17 landing of the Hwasong-14 ICBM, thanks to tracking by the Japanese Defence Force and US STRATCOM, as well as visual confirmation from land in Japan. The remaining positions are less precise, but in an overall view, the area affected is quite well defined – south of AVGOK and north of KADBO. In 2017, there have been 6 distinct missile landings in this area. The primary airways affected are B451 and R211, as shown on the chart.

So, in a very specific portion of Japanese airspace, there have been regular splashdowns of North Korean missiles. As highlighted by the Air France 293 coverage, this area is crossed by several airways in regular use, predominantly by Japan-Europe flights using the Russia route.

Determining Risk

The critical question for any aircraft operator is whether there is a clear risk from these missiles returning to earth through the airspace in which we operate. Take these considerations into account:

– The regularity and range of the launches are increasing. In 2015, there were 15 launches in total, of short-range ballistic and sub-launched missiles. In 2016, there were 24 launches, almost all being medium-range. In 2017, there have been 18 so far, with the first long-range missiles.

– In 2016, international aviation solved the problem by avoiding the Pyongyang FIR. This is no longer sufficient. The landing sites of these missiles have moved east, and there is a higher likelihood of a splashdown through Japanese airspace than into North Korea.

– Almost all launches are now in an easterly direction from North Korea. The launch sites are various, but the trajectory is programmed with a landing in the Sea of Japan. From North Korea’s perspective, this provides a sufficiently large area to avoid a missile coming down on land in foreign territory.

– The most recent ICBM failed on re-entry, breaking up into many fragmented pieces, creating a debris field. At about 1515Z on the 28th July, there was a large area around the R211 airway that would have presented a real risk to any aircraft there. Thankfully, there were none – although the Air France B777 had passed through some minutes before.

– Until 2014, North Korea followed a predictable practice of notifying all missile launches to the international community. ICAO and state agencies had time to produce warnings and maps of the projected splashdown area. Now, none of the launches are notified.

– Not all launches are detected by surrounding countries or US STRATCOM. The missile flies for about 35 minutes before re-entry. Even with an immediate detection, it’s unlikely that the information would reach the Japanese radar controller in time to provide any alert to enroute traffic. Further, even with the knowledge of a launch, traffic already in the area has no avoiding option, given the large area that the missile may fall in.

Can a falling missile hit an aircraft?

What are the chances? Following the AFR293 report on July 28, the media has favoured the “billions to one” answer.

We don’t think it’s quite as low.

First of all, that “one” is actually “six” – the number of North Korean missiles landing in the AVGOK/KADBO area in 2017. Considering that at least one of them, and maybe more, broke up on re-entry, that six becomes a much higher number.

Any fragment of reasonable size hitting a tailplane, wing, or engine as the aircraft is in cruise at 450 knots creates a significant risk of loss of control of the aircraft. How many fragments were there across the six launches? Maybe as high as a hundred pieces, maybe even more.

The chances of a missile, or part of it, striking the aircraft are not as low as it may initially appear. Given that all these re-entries are occurring in quite a focused area, prudence dictates considering avoiding the airspace.

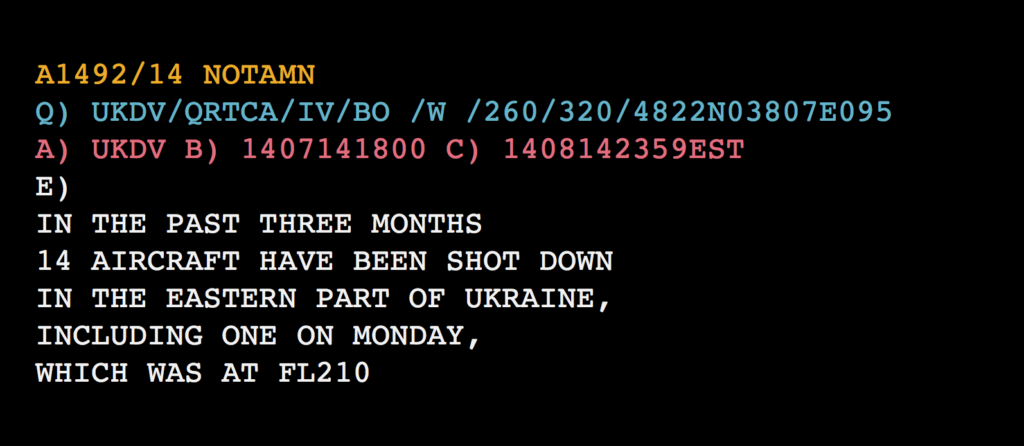

What did we learn from MH17?

Whenever we discuss missiles and overflying civil aircraft in the same paragraph, the valuable lessons from MH17 must be remembered. In the weeks and months leading up to the shooting down of the 777 over Ukraine, there were multiple clues to the threat before the event happened.

Of greatest relevance was that State Authorities did not make clear the risk, and that even though five or six airlines decided to avoid Ukrainian airspace, most other operators did not become aware of the real risk level until after the event.

Our mission at Flight Service Bureau is to make sure all aircraft operators, crews, and dispatchers have the data they need to make a fully informed decision on whether to continue flying western Japan routes, or to avoid them.

Guidance for Aircraft Operators

– Download OPSGROUP Note to Members #30: Japan Missile risk (public version here)

– Review the map above to see the risk area as determined by the landing sites in 2017.

– Consider rerouting to remain over the Japanese landmass or east of it. It is unlikely that North Korea would risk or target a landing of any test launch onto actual Japanese land.

– Check routings carefully for arrivals/departures to Europe from Japan, especially if planning airways R211 or B451. Consider the previous missile landing sites in your planning.

– Monitor nti.org for the most recent launches, as well safeairspace.net.

– OPSGROUP members will be updated with any significant additions or updates to this Note through member mail and/or weekly newsletter.

References

– Nuclear Threat Initiative – nti.org

– Opsgroup Note to members #30 – Public version

– OPSGROUP – Membership available here.

– Weekly International Ops Bulletin published by OPSGROUP covering critical changes to Airports, Airspace, ATC, Weather, Safety, Threats, Procedures, Visas. Subscribe to the short free version here, or join thousands of Pilot/Dispatcher/ATC/CAA/Flight Ops colleagues in OPSGROUP for the full weekly bulletin, airspace warnings, Ops guides, tools, maps, group discussion, Ask-us-Anything, and a ton more.

– Larger area map of Japan airspace risk 2017

– Contact news@ops.group with any comments or questions.

More on the topic:

- More: Japan BizAv Ops: Haneda, Narita, and Nagoya Explained

- More: South Korea Airspace Risk Update

- More: Japan Boosts ATC Procedures and Lessons from Haneda

- More: Asia Airspace Risk: Why North Korea’s Lastest Launch Matters…

- More: Get ready for more North Korean missiles

More reading:

- Latest: FAA Warns on Runway Length Data and Overrun Risk

- Latest: EASA’s New Cyber and Data Risk Rule for Operators in Europe

- Latest: Airport Spy: Real World Reports from Crews

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly

2 Comments