On Jan 21, the FAA issued a new Information Note for Operators after identifying cases where incorrect runway length data was being used for performance planning.

The concern is straightforward. Using the wrong numbers can skew takeoff or landing calculations, which is why the FAA says performance planning should be based on declared distances from the Chart Supplement.

What exactly is the issue?

The FAA notes that many crews default to runway lengths taken from airport diagrams, charts, FMS databases or commercial planning tools.

The issue is that these sources may not include declared distances (TORA, TODA, ASDA and LDA) which are the figures used to meet regulatory performance requirements and can differ significantly from the physical runway length.

The FAA’s concern is that crews may misunderstand declared distances, omit them entirely, or rely on FMS or third-party data that has not been updated after changes.

So a quick clarification on how runway lengths are defined helps…

About runways

When we talk about default runway length, we are talking about the physical length of the runway surface. It’s what you see on charts, airport diagrams and other sources of info.

It represents exactly that – pavement from end to end. It may include unusable bits (such as displaced thresholds, closed portions etc) and is often a single number with no context.

It doesn’t tell you how much runway is legally available for takeoff or landing and can significantly overstate what you can actually use (more on that later).

Declared distances, on the other hand, are the official, performance-relevant runway lengths published by the airport authority via the FAA Chart Supplement and other validated sources.

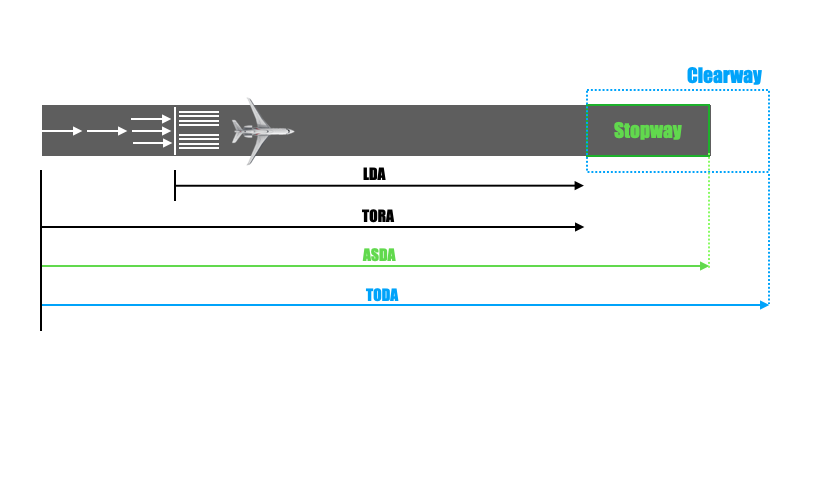

A brief reminder of what these distances include (and critically, don’t):

Takeoff Run Available (TORA). Think of this as how much runway you can accelerate on. It includes useable pavement only, starting at the take-off threshold. It doesn’t include clearways or stopways.

Takeoff Distance Available (TODA). How much distance you have to get airborne (i.e. TORA) plus the distance required to clear obstacles in the initial climb segment (clearways). Crucially, it doesn’t include stopways (usable in a rejected takeoff).

Accelerate-Stop Distance Available (ASDA). Think of this of how much distance you have if you reject the takeoff. It includes TORA and stopways. It doesn’t include clearways.

Landing Distance Available (LDA). How much runway you actually have to stop after touchdown. This includes usable pavement from the landing threshold to the end of the runway. It doesn’t include pavement before a displaced threshold, stopways or clearways.

Here’s what this all looks like:

Under the FAA regs, these distances are the authoritative performance numbers. They override any single runway length shown elsewhere. That’s the key point.

Under the FAA regs, these distances are the authoritative performance numbers. They override any single runway length shown elsewhere. That’s the key point.

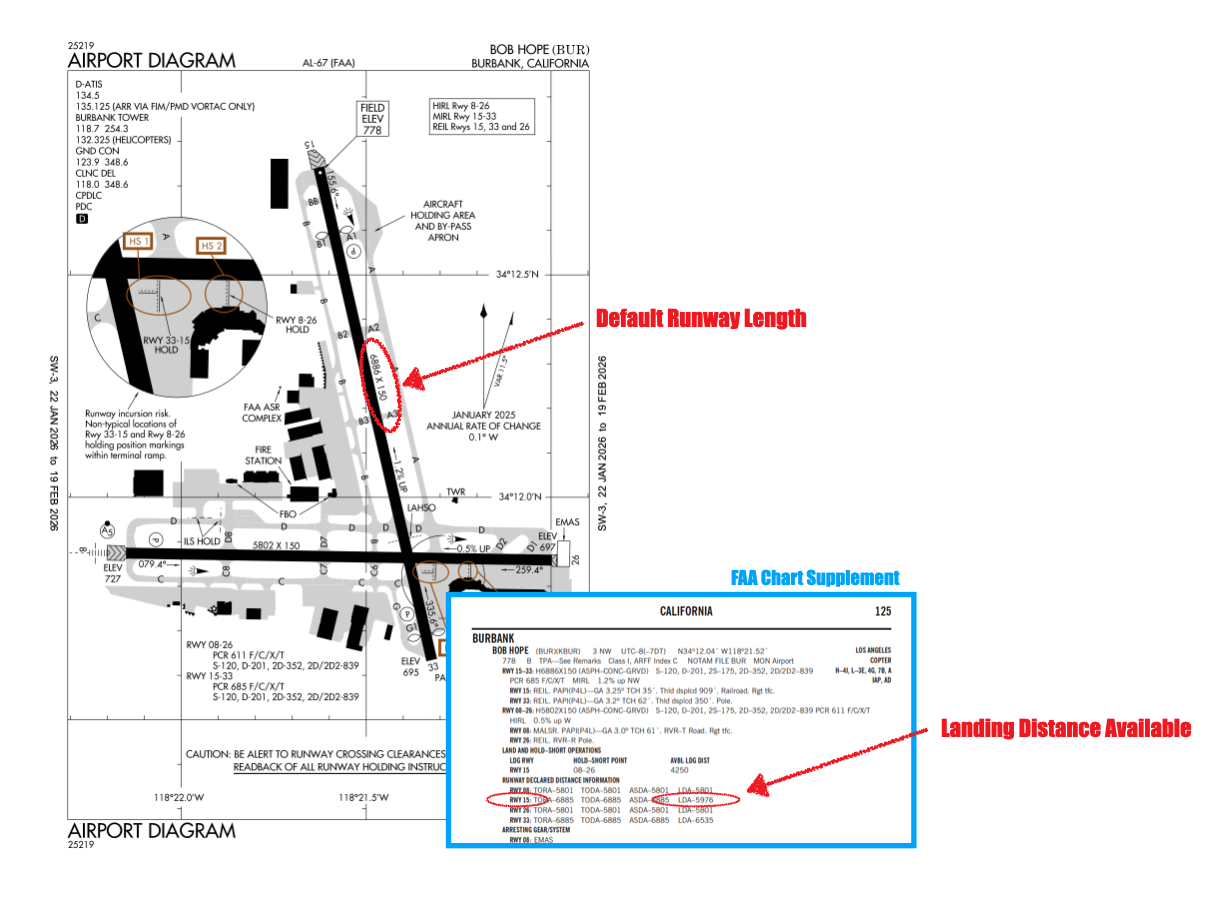

Real world example

But that’s enough theory. A good real-world example is KBUR/Burbank Runway 15, where the published runway length and the declared landing distance are not the same.

Many charts and planning tools show a runway length of 6,886 ft. But the FAA Chart Supplement lists an LDA of 5,976 ft due to a displaced threshold for obstacle clearance.

If crews plan landing performance using the longer figure, they may be overestimating available runway by about 900 ft. Add tailwind, a wet surface, or a performance-limiting MEL, and that margin can disappear quickly.

That’s exactly the scenario the FAA is trying to prevent.

So what’s the FAA’s advice?

For performance calcs, the FAA says crews should use published declared distances, not the physical runway length. Just because pavement exists doesn’t mean it’s legally usable.

That expectation needs to be reflected in procedures, training and day-to-day practice.

Crews also need to be clear on which runway lengths their performance tools are actually using.

Be aware that the FMS runway length is not LDA, ASDA or TODA.

Operators should also review FMS databases and third-party performance tools, understand their limitations, and check that the data is current.

Have you spotted something risky out there?

Share it (anonymously) with the group! You can reach us via blog@ops.group, Airport Spy or Report-A-Thing.