Two years have passed since we published our original piece on QNH errors, and the issue hasn’t gone away. In fact, there have been more serious incidents linked to incorrect altimeter settings below transition. Here’s what’s happened since then.

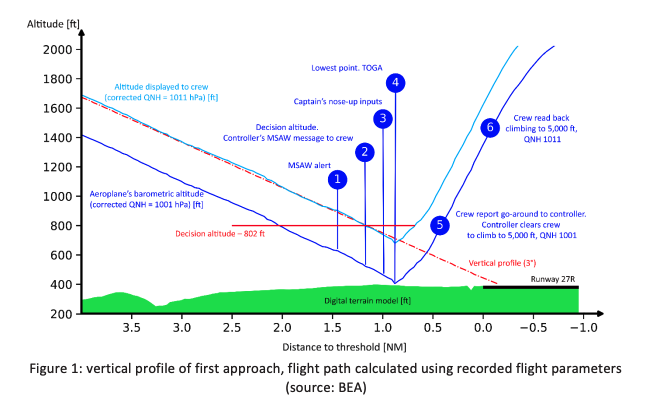

The Paris Near Miss

The final report is out on a serious incident at LFPG/Paris Charles de Gaulle in May 2022. An A320 was flying an RNP approach (LNAV/VNAV minima) in IMC when ATC passed the wrong QNH – 1011 instead of 1001, a 10 hPa difference.

That mistake meant the aircraft flew the approach about 280 feet lower than it should have. A ground proximity alert went off in the tower, but the controller got no reply from the crew.

At minima, with no runway in sight, the crew went around. The aircraft’s radio altimeter later showed a minimum height of just six feet – one mile short of the threshold.

The crew never realised. The wrong QNH made their instruments show they were higher than they actually were, so everything looked normal. The heights matched the chart, and EGPWS didn’t trigger.

They tried again, still with the wrong QNH set. This time they broke out and landed safely, again passing within a few feet of the surface before the threshold.

The aircraft reached a minimum height of just 6 feet, almost a mile from the threshold.

You can read the full report and safety recommendations here.

Updated EASA Guidance

On October 22, EASA reissued its Safety Information Bulletin (SIB) on incorrect barometric altimeter settings. You can download it here. It warns that QNH errors can not only lead to CFIT but also reduce separation from other aircraft, increasing the risk of midair collision.

This applies to all phases of an instrument approach, including the missed approach.

The SIB points out that QNH errors can creep in at several points – from how meteorologists determine it, to how ATC passes it, to what the crew actually sets.

The SIB contains some valuable recommendations for operators:

- Develop SOPs to make sure pilots cross-check QNH from at least two independent sources (for example, ATIS and ATC). Don’t rely on handwriting or word-of-mouth!!

- Assess these procedures, and hunt for ways in which errors may still occur. Then continue to refine them.

- Use FDM or FOQA data to flag and investigate any altimeter mis-sets and learn from them.

Our Original Article

If you fly any baro-based approach (that’s most of them except ILS, GLS, or RNP to LPV) you need to know how a simple QNH mistake can put you below profile without you realising it.

Back in 2023, ICAO put out a warning about this. Here’s the quick version:

Key Points

- QNH errors have led to several serious approach incidents.

- Affected approaches: VOR, NDB, LOC, RNP, and RNP AR.

- Main causes: bad data, misheard ATC calls, and cockpit workload.

- Fix: raise minima, stick to SOPs, cross-check QNH from two sources, and speak up if it sounds wrong.

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing

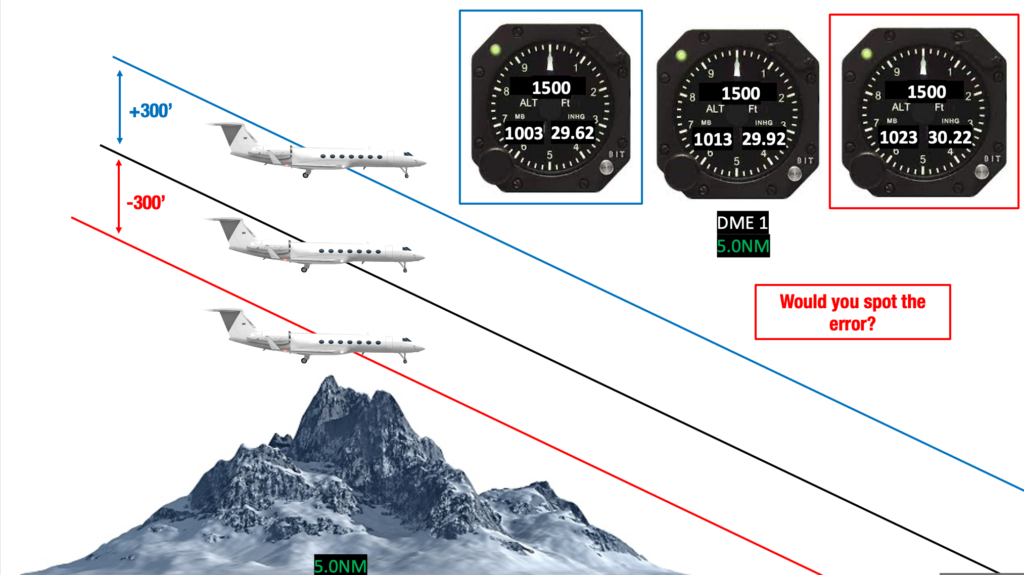

![]() An innocuous QNH error can easily place your aircraft hundreds of feet below profile in the final approach segment of a non-precision approach. And there may be very few signs – save for our eyeballs, our radio altimeter, or ultimately our EGPWS.

An innocuous QNH error can easily place your aircraft hundreds of feet below profile in the final approach segment of a non-precision approach. And there may be very few signs – save for our eyeballs, our radio altimeter, or ultimately our EGPWS.

And perhaps the approaches most vulnerable to this threat are those which use BARO-VNAV – in other words, the use of our aircraft’s barometric altitude information to compute the aircraft’s vertical guidance.

The problem is that to fly these approaches safely, our altimeters must be accurate. That entirely depends on pilots setting the correct QNH. It is a simple task riddled with potential for insidious errors – something that no pilot (or controller) is immune to.

Which is why ICAO recently published a new Ops Bulletin on this very problem. They can’t fix it, but they can help mitigate it. Here’s a run-down on what they had to say.

Risky Business

If you’re reading this, chances are you have a reasonable idea about how an altimeter works. In the most basic sense, we calibrate these pressure-sensitive devices to provide an altitude above whatever datum we need them for – in most cases, sea level.

This essentially creates potential for two errors:

- Temperature: although this is less of an issue, because we can anticipate and correct for it.

- A mis-set: or in other words, rubbish in rubbish out. The altimeter doesn’t know if it’s telling you lies. In the same sense that a conventional clock doesn’t know that it’s wrong – it just runs from whatever time you set it to. The consequences of this type of error are far worse.

Final Approach

ICAO’s Bulletin focuses on the final approach (inside the FAF) simply because this is where altimeter errors become most critical.

In this segment, ICAO-compliant procedures only guarantee a smidge less than 300 feet of obstacle clearance (ICAO Doc 8168 Vol II if you’re feeling bold). Interestingly, this almost perfectly correlates to an altimeter error of 10hPa…

Are you sure that 1023 QNH you just heard on that scratchy ATIS wasn’t actually 1013?

…it’s easy to see how critical errors can become. Like the example below:

Which approaches are affected?

It can be easy to get lost in the sea of acronyms out there. So let’s keep it simple:

Not vulnerable: ILS, GLS, and RNP to LPV minima. In other words, approaches that do not rely on barometric altitude to fly the correct profile. One gotcha tho – DA is still based on your altimeter. You may therefore go around early or late with an incorrect QNH but the profile itself will still be correct.

Vulnerable: Everything else – including VOR, NDB, LOC, RNP, and RNP (AR).

Why are QNH errors happening?

ICAO has some ideas:

Bogus Data: This may be incorrect information supplied by a met service provider, corrupt hardware on the ground or even by assuming area QNH will be close enough to airport QNH.

Chinese Whispers:Don’t underestimate the power of what you think you heard. This can happen anytime we are relying on voice to communicate safety critical information. It’s not just pilots either – ATC may not pick up that your read-back was incorrect. If you fly internationally, the language barrier can also be a challenge. Even domestically we form habits of talking at speed on the radio. If there is any doubt, use the phrase “Say Again Slowly.”

Workload: Have you ever been in this boat? You’re passing through transition, changing to an approach frequency, slowing to 250kts, securing the cabin and trying to run an approach checklist….all at the same time. Depending on where the transition level is (for example, FL110 in Australia) it can clash with your other flight deck duties. Crew confusion, miscommunication and even finger trouble can come into play here.

What can we do about it?

Consider other approaches: iI there’s an ILS or similar available and conditions are poor, consider using it instead.

Think about minimas: ICAO suggest raising your minima particularly if you are unfamiliar with an approach type.

Stick to the SOPs: and cross check. Treat QNH like that stove you think you left on every time you leave for a multi-day trip. Become paranoid and find that error. Cross-check the QNH across multiple sources – at least two independent ones for each and every approach.

Don’t forget to ask yourself – is it sensible? A good way to cross check this is by comparing the ATIS QNH to the TAF or METAR QNH. If there is any doubt, confirm it with ATC.

Be especially suspicious of anything hand-written: If you’ve obtained a QNH by voice, make sure you have both independently heard it.

Be careful with anything hand written. Is our arrival info Q 1014 or could it be O 1019?

Don’t forget other sensibility checks: Terrain permitting, your radio altimeter may give you an early clue that all is not right – especially if you’re over flat terrain or water.

ICAO also suggests that ATCOs and ANSPs have a role to play too: It’s little beyond the scope of this article, but you can find that info in the very same bulletin.

Have a story to tell?

Please share it with us in confidence. You can reach us on team@ops.group.

More on the topic:

More reading:

- Latest: Crisis in Iran: Elevated Airspace Risk

- Latest: EU-LISA: The BizAv Guide

- Latest: Greece Winter Runway Closures

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly

Just flew the LLBG KTEB route, no spoofing or jamming, coming or going.

We did get the msg from Shanwick. Called them on VHF, They kindly explained the message, and asked if we had been spoofed or jammed. Since we we hadn’t been, end of conversation. I did however confirm with Shannon that our track matched their radar tracking of our flight.

We were already at our initial crossing Altitude of FL450.