- Flying to an airport in the US?

- Want to land on the actual runway, rather than some taxiway or dirt road which looks a bit like the runway?

- Not afraid of some basic pics showing you how NOT to mess it up?

Well then today’s your lucky day, friend!

Step right this way!

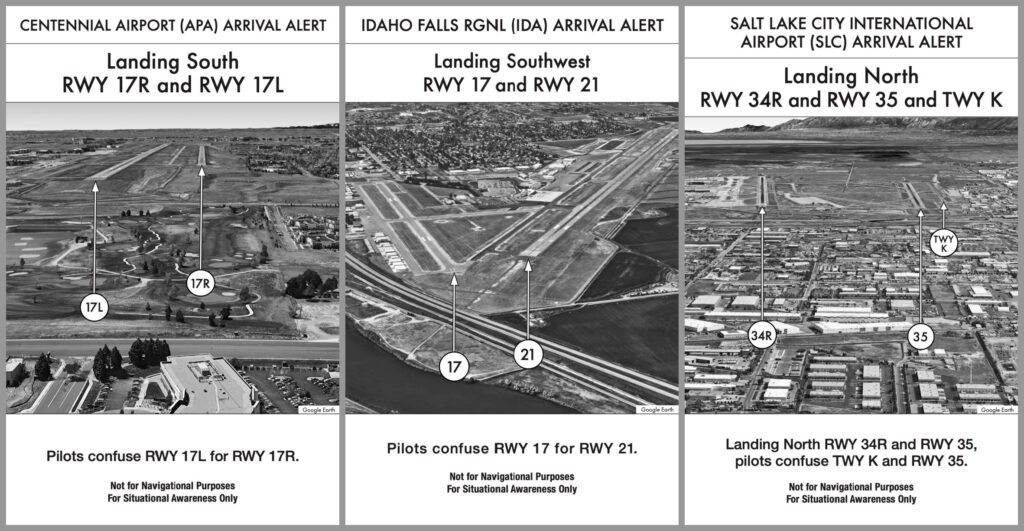

Arrival Alert Notices

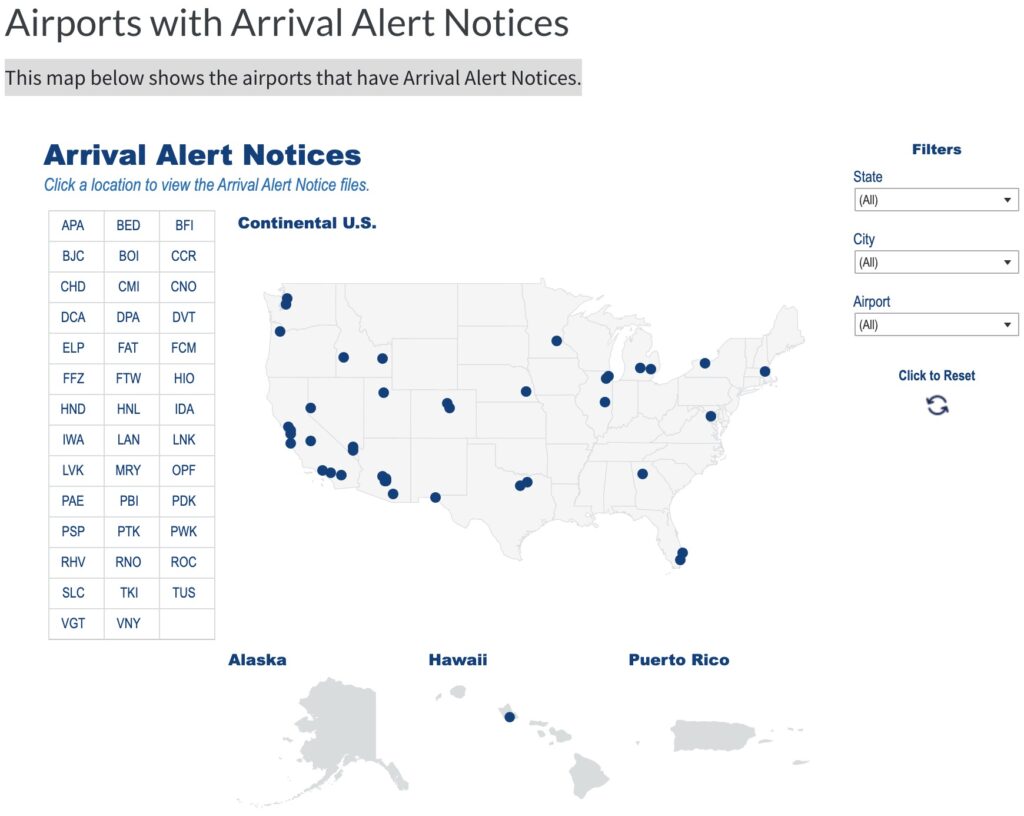

The US FAA has published things called Arrival Alert Notices at several airports with a history of “misalignment risk” – i.e. where aircraft line up to or land on the wrong runway, taxiway, or even sometimes the wrong airport.

The best thing about these Notices is that they are dead simple. No superfluous symbology, no weird language, just a nice big picture of the runway with a clear instruction on what to do.

Soothing 1950’s greyscale. Quietly reassuring Futura typeface.

The FAA published the first batch of these in May 2022, and then a whole bunch more in Jan 2024. So they now have them for 41 airports in total, all of which have a history of misalignment risk or “wrong surface events” – i.e. times where folks landed on something other than the actual runway.

They say that many of these wrong surface events occur “during the daytime and in visual meteorological conditions, and the majority of the time, the pilot has read back the correct landing clearance.” In other words, folks have got it wrong even at the best of times, so it’s probably worth a quick glance at these docs.

Which Airports?

This map on the FAA AAN site shows the airports that have Arrival Alert Notices.

What else is the FAA doing to improve safety?

A whole bunch of things. You can read all about it on their Runway Safety site, but here’s a summary. And as a cheap marketing trick by way of parting, I will say that the last one on this list is probably the best – so make sure you read to the end!

- Runway Status Lights (RWSL): In operation at 20 airports, signals potential hazards through illuminated red lights on runways and taxiway/runway crossings. More info.

- Airport Surface Detection Equipment, Model X (ASDE-X): In operation at 35 airports, integrates various data sources to provide ATC with better aircraft positions, and pings up alerts for potential traffic conflicts. More info.

- Airport Surface Surveillance Capability (ASSC): Similar to ASDE-X, ASSC operates at 9 airports, works in all kinds of weather, and lets ATC see aircraft on approach and departure within a few miles of the airport. More info.

- ASDE-X and ASSC Taxiway Arrival Prediction (ATAP): ATAP is an enhancement to the previous two, and alerts ATC when an aircraft is aligned with a taxiway instead of the runway. In operation at these airports.

- Engineered Material Arresting System (EMAS): We like these things so much, we wrote an article on them. Installed at 70 airports, EMAS are those crushable bits of tarmac at the ends of runways which you can plough into to stop overruns. Very cool. More info.

- Electronic Flight Bag (EFB) with Moving Map Displays: Everyone loves their EFBs and moving maps. So do the FAA – they encourage pilots to use them!

- Runway Safety Areas (RSA): Because many runways were built before the 1000-foot RSA standard was adopted, the FAA implemented the Runway Safety Area Program which made improvements to over 1000 runways at 500 airports.

- Runway Incursion Mitigation (RIM): A national initiative identifying and mitigating specific risks at 80 airports that might lead to a runway incursion. Things like: unclear taxiway markings, airport signage, runway or taxiway layout.

- Hot Spot Standardization: The FAA now has standardized hot spot symbology on their airport charts. We wrote about this here.

- Arrival Alert Notices: i.e. this article!

- Automated Closure Notice Diagrams: They now have a site where you can get a big airport chart showing all the runway or taxiway closures on it. It looks like AI might be involved behind the scenes on this one, so it’s a bit clunky for some airports, but it’s still pretty cool. Check it out here.

- “From the Flight Deck”: This might just be the best of the bunch! This FAA website basically has videos showing how to land at specific airports (real footage), plus a bunch of other useful info: hotspots, things local ATC want pilots to know, airport comms, airspace details and other preflight planning resources. Take a look here!