As we know by now, at 23:35Z last night (June 19, UTC), Iran shot down a US UAV on a high-altitude recon mission in the Straits of Hormuz. This was no small incident. The UAV was a $200 million aircraft, weighing 32,000 lbs, with the same wingspan as a 737.

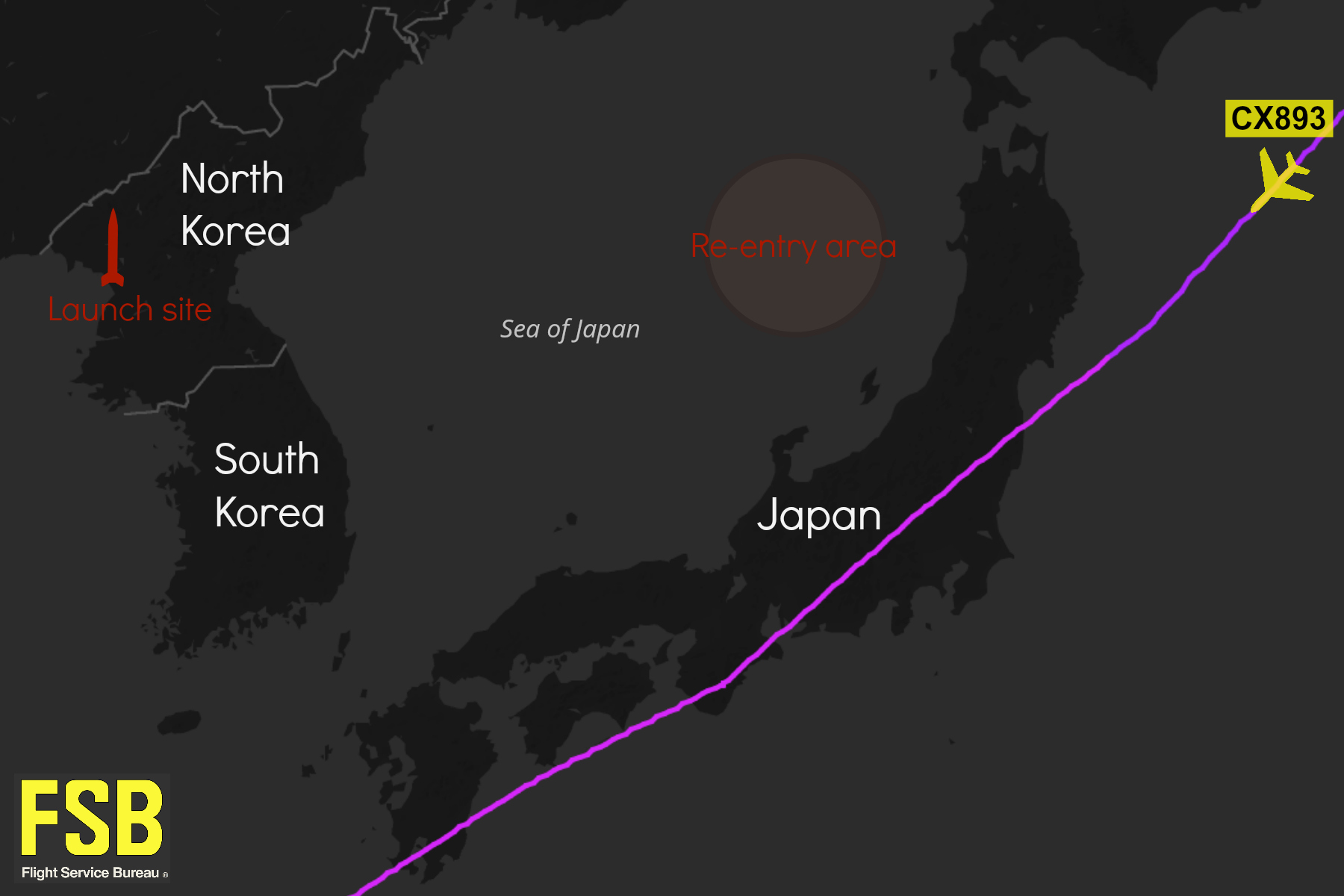

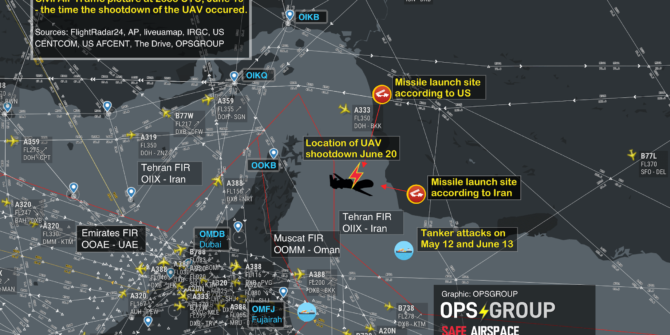

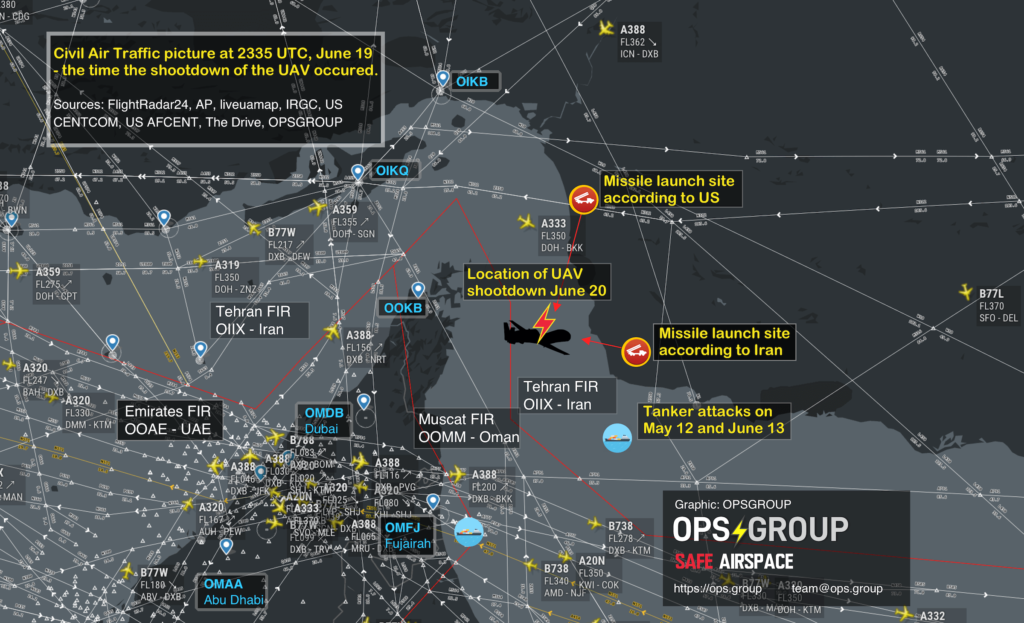

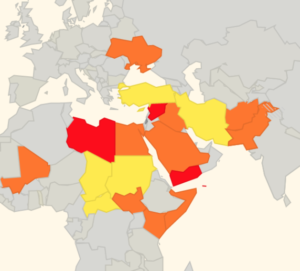

Although Iran and the US have slightly different versions of the position of the shooting down in the media, the approximate area is very clear, and marked on the map below, which shows the airspace picture at 2335Z, the time of the shootdown.

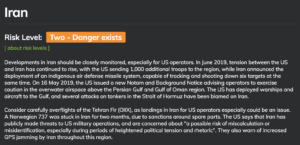

A high-res version of this map is available here.

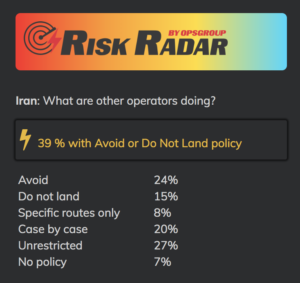

For civil operators, the Straits of Hormuz have always been an area of high military activity, so it’s tempting to mark this as ‘more of the same’. However, over the last few weeks tension between the US and Iran has heightened, and the launching of a surface to air missile by Iran represents an escalation in the current situation that crosses a threshold – warranting a very close inspection by airlines and aircraft operators overflying, or using airports like Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Ras Al Khaimah, Muscat, and Fujairah.

As we approach five years since MH17, we should remember the build up to that shootdown took several months, and there are the warning signs here that we must pay close attention to. In the lead up to MH17, 16 military aircraft were shot down before MH17 became the 17th. Look closely at the map. Civil aircraft were very close to the site of this incident.

This morning, we sent this out to our members in OPSGROUP:

OIZZ/Iran Earlier today, a large US military drone was shot down by Iran over the Strait of Hormuz. The US say it was over international waters, Iran say it was within their FIR. Either way, it means that SAM missiles are now being fired in the area, and that represents an escalation in risk. It appears a 787 was very close to the missile site this morning. Avoiding the Strait of Hormuz area is recommended – misidentification of aircraft is possible. If you are coming close to Iran’s FIR, it’s essential that you monitor 121.5, as Iran uses this to contact potentially infringing aircraft. Local advice from OPSGROUP members says ‘Even if the operator/pilots think they will come close or penetrate Irans Airspace they should contact Iran Air Defense on 127.8 or 135.1’. If the Iranians have an unidentified aircraft on their radar and not in contact with them they will transmit on guard with the unidentified aircraft coordinates, altitude, squawk (if there is one), direction of travel and then ask this aircraft to identify themselves as they are approaching Iranian ADIZ. Monitor safeairspace.net/iran for the latest.

Last September, when Syria shot down a Russian transport aircraft, we published an article on that risk, and noted “50 miles away from where the Russian aircraft plunged into the sea on Monday night is the international airway UL620, busy with all the big name airline traffic heading for Beirut and Tel Aviv. If Syria can mistakenly shoot down a Russian ally aircraft, they can also take out your A320 as you cruise past.” That same risk of misidentification exists here in the Straits of Hormuz.

Apart from the misidentification risk, is the risk of a problem with the missile itself. The missile used by Syria in September was a Russian S-200 SAM, which was the same missile type that brought down Siberian Airlines Flight 1812 in 2001. The missile can lock on to the wrong target, and this risk is higher over water. The missile system used by Iran last night was a domestically-built Raad Anti-Aircraft system, similar to the Russian Buk that was used against MH17. Any error in that system could cause it to find another target nearby – another reason not to be anywhere near this part of the Straits of Hormuz.

Bear in mind that as an aircraft operator you won’t be getting any guidance from the Civil Aviation Authorities in the region. As we saw with Syria, even when an aircraft had been shot down on their FIR boundary, the only Notams from Cyprus were about firework displays at the local hotels. It won’t be any different here. You need to be the one to decide to avoid the area.

A further risk, if you needed one, is retaliation by the US. It seems probable that the US will at least try to find an Iranian target to make an example of. If you recall the Iran Air 665 tragedy, back in July 1988, which occurred in the same area, the US mistakenly shot down that aircraft thinking it was an Iranian F-14.

Bottom line: we should not be flying passenger aircraft anywhere near warzones. That’s the lesson from MH17, and that’s the lesson we need to keep applying when risks like this appear on our horizon.

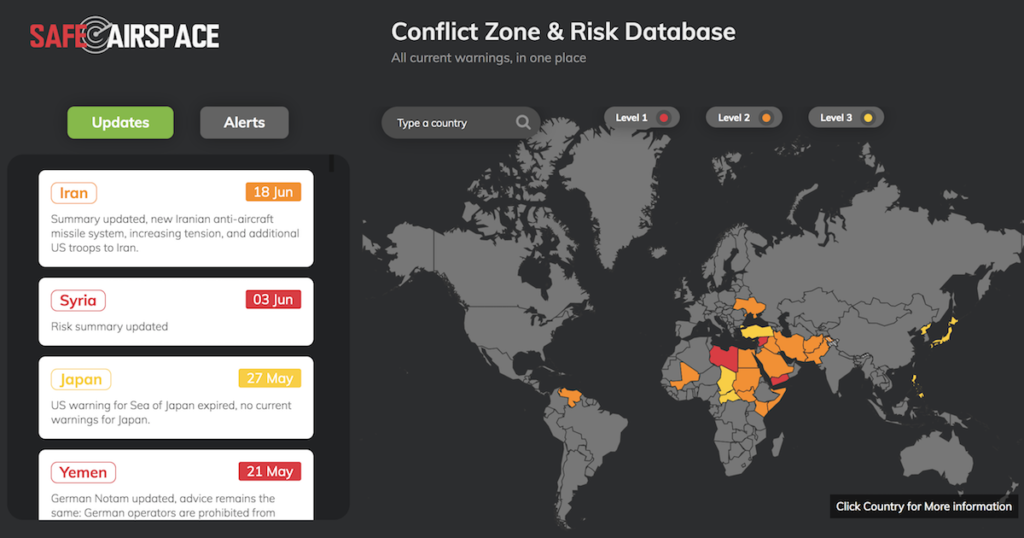

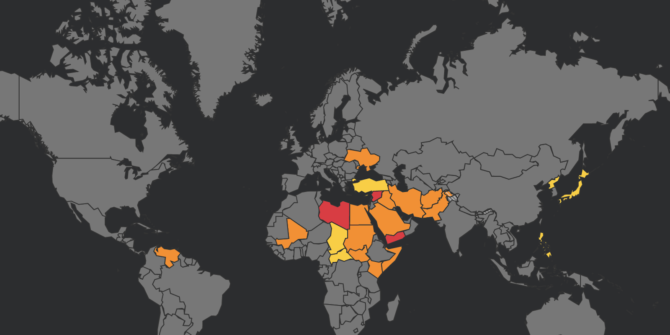

The Iran risk is being monitored at Safe Airspace – the Conflict Zone & Risk Database. The Iran country page also has more information on further overflight considerations in other parts of the Tehran FIR.

Further reading:

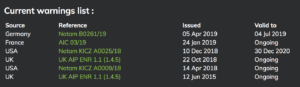

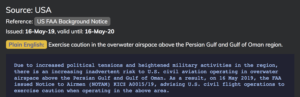

- The FAA published guidance in May that we have previously reported on and is still very much valid.

Sources for this article:

What are surface-to-air missiles, and who has them?

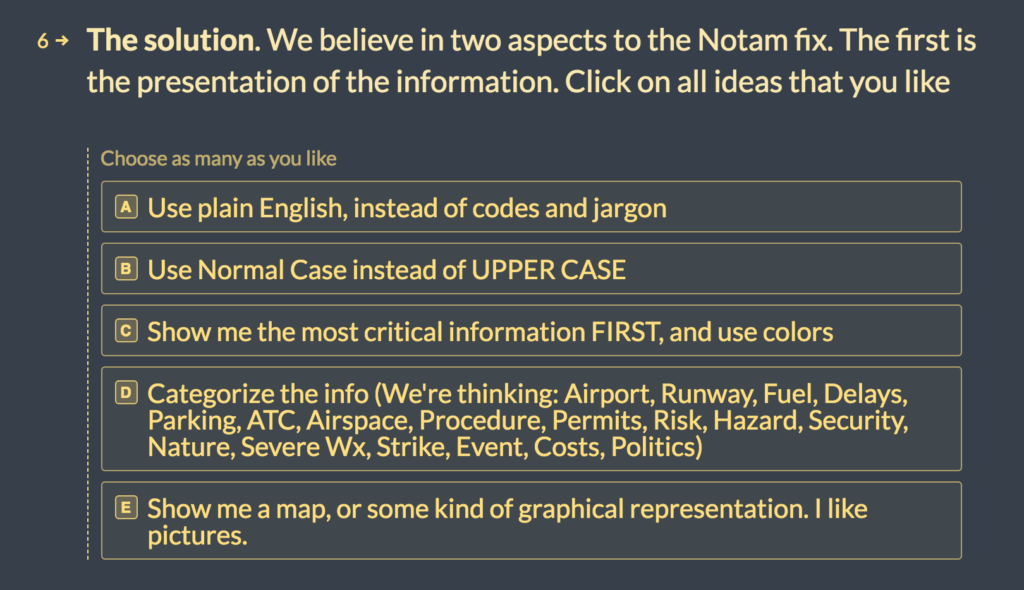

What are surface-to-air missiles, and who has them? There is some evidence to suggest that more States are starting to provide better guidance and information to assist operators in making appropriate routing decisions, but we think this still has some way to go.

There is some evidence to suggest that more States are starting to provide better guidance and information to assist operators in making appropriate routing decisions, but we think this still has some way to go.