How many pilots can stick their hand up and say they’ve taken control from another pilot?

A more interesting question though might be – how many can recall a time when they didn’t take control but felt they should have? Because this is now getting somewhere – this is what we need to be thinking about. Why, if it was apparent that we should have taken control, didn’t we?

It’s happened before, it will again.

In 2016 a Global 5000 was routing from ZBAA/Beijing to VHHH/Hong Kong. During the approach they lost their ‘mental picture’ of the situation and descended below their cleared altitude leading to a pretty significant loss of terrain clearance.

There are a lot of why’s and how’s and other factors which led to this, but one particularly interesting point that stood out was the First Officer’s comments in a subsequent interview about the incident.

“… he [the captain] has a very aggressive attitude… it causes problems if I don’t do things his way… I had my hands on the controls, but I couldn’t take over…”

How does it get to that point?

Taking over control is something that in many cases pilots say they should have, could have, or someone else probably would have avoided. We are not talking the immediate, time-critical, co-pilot-hasn’t-flared-and-you-have-less-than-3-seconds-to-fix-it type situations, or the rolling-down-the-runway-and-the-other-pilot-has-just-passed-out sort of thing.

We are talking about those times when a Swiss cheese model of insidious, minor or ambiguous events has built up. When there have been clues, hints and opportunities to spot ‘holes lining up’ and where we potentially could have identified that something big might happen if we don’t set ‘safety’ back on track.

In these situations, reaching a point where we have to take control is too close to the line, it is not somewhere we ever want to reach. So what ways are there to ‘redirect’ safety and prevent it from reaching the “I have control?” stage?

The Intervention Model.

‘ASDT’ is an acronym many airline pilots might be familiar with. Ask, Suggest, Direct, Takeover. The idea is we intervene based on how much, or rather how little time we have left to fix whatever situation is unfolding. If you haven’t heard of that then RAISE right ring a bell – it is a similar model.

So how do we apply it? Well, if we are lazing along in the cruise and ATC ask us to take up a heading, and the pilot flying dials in the wrong one, we probably aren’t going to yell “I have control!” Asking a simple “Can I confirm the heading, that isn’t what I heard?” question is enough. It is appropriate. We have time.

On the other hand, if ATC has told you to turn immediately to avoid a traffic conflict, and the other pilot then turns the wrong way towards the traffic then you might find yourself moving into the suggest or even the direct “Negative! Turn right heading 360 now!” stage. There is less time, but there is still time to correct it without taking control.

ASDT, RAISE (or any others you might know) require an assessment of urgency, or criticality of action versus time. It sounds simple, and generally it is when the situation is clear cut, right or wrong, time or no time. The difficulty for many pilots comes when they are faced with something that isn’t a clear breach in SOPs, or an obvious error, but when it is more of a “feeling” or a comfort level in a grey area of right or wrong, OK or not OK.

When it is a sense that something might not be right, or when that ‘not rightness’ might actually be with the other person or their attitude rather than a clear action or moment, then this can be hard to deal with under an intervention model. If we can’t identify what it is that makes us think there is a potential for things to go wrong, then what should we ask?

Challenging or intervening when we don’t really know what to challenge or where to intervene is not going to result in good CRM.

What’s your safe word?

“I am uncomfortable” is a ‘safe word’, or rather phrase, that one major airline encourages its pilots (particularly the First officers with an emphasised “Captain” at the start of the phrase) to use.

It is an indication to the other pilot that perhaps you don’t understand a situation, that they haven’t “shared their mental model” well with you. It is asking, suggesting and directing the other pilot all at once to consider that there might be something causing the other to question if the situation could become unsafe at some point.

It is phrase I have used, as a less experienced First Officer, when I felt a Captain was not taking a large cloud on the approach as seriously as I thought we should. It caused him to slow down and talk me through his thought process. Turns out his judgement and experience was sound and it was just me and my lack of experience that had made me unsure.

I could have asked him outright “do you think we should avoid the cloud?” but this might have only earned me a “No, I don’t” – and that hasn’t provided me with anything to remove my uncertainty.

“I am uncomfortable” is not the phrase to use when the other pilot is outside of the localiser limits and still isn’t correcting. It is the phrase to use if they have chosen to hand fly in gusty winds and are starting to chase the localiser. It wasn’t the phrase to use during the Global 5000 VHHH incident when the Captain exceeded 44° of bank, but it might have helped the situation if it had been asked earlier when the Captain first said he was going to disconnect the autopilot.

Reaching the point of no return.

But all this asking, suggesting, directing and saying “I am uncomfortable” might not prevent a situation reaching a point when taking control is necessary, and when that point is reached action has to be taken, and so it is worth thinking about what it really means to do that.

Taking control from the other pilots means you are effectively removing them from that stage of the flight. It is placing you in a single pilot operation and it breaks down the CRM and communication entirely, for that moment. While it might be absolutely required, it also might mean a very challenging few moments for you.

So considering ‘what happens next?’ is critical because you are going to have to manage that workload, the increase in pressure and the responsibility to maintain safety on your own in what will likely be a very dynamic situation. If you are not prepared it might rapidly place you, and the flight, in an even more dangerous situation.

At some point you are also going to have to rebuild the CRM by bringing the other pilot back into the picture and to do this you will need to have the aircraft in a safe position with time on your hands to do so. This isn’t always as easy as it sounds and unfortunately, we rarely train for it.

A pilot intervention with the automation is one thing, but intervening with another person, (and where their pride and ego is involved), can be quite another.

Why don’t we take control?

We ran a mini poll and asked people what they think the main reasons were for pilots not taking control.

The main reason most folk thought was a lack of situational awareness – the other pilot also not knowing what was going on. This seems to be the main factor in the Global 5000 VHHH incident. Loss of situational awareness is a tough one to spot but sticking to SOPs, briefing well, and proactive threat and error management seems to be the best defence.

Second up was the cockpit gradient issue – the First Officer feeling unable to question the Captain due to a too steep gradient. This is where using a safe word or intervention model might help. But at the end of the day, both pilots remain equally responsible for safety, so if something ain’t right, speak up – we should be more afraid of the repercussions of not doing so than of any grumpy reaction we might experience.

The When, the How and the Why.

We might have done pilot incapacitation training where the other pilot has mysteriously frozen at “rotate”, but few will have really trained to a comfortable, competent level where we can easily identify what stage of intervention might be most appropriate. We rarely practice insidious, developing situations which are filled with grey areas. Fewer still will have experienced what the reality of taking control, and then ‘bringing the other pilot safely back into the picture’ really means.

The best way to prepare for this is to think about it, talk about it and consider it in advance. Understand our comfort levels, know when we would react and how we would do it, and talk this through with other people so we can share experience and learn from one another.

Introducing: Danger Club

Aviation changes constantly – new airplanes, new routes, new rules, new risks. Something that isn’t changing, however, is accidents. If the return to service and industry growth being talked about is anything like what’s forecast, we’re going to need even more focus on the “why” of things going wrong.

So, we want to create a safe space to talk about this – as people, not as companies or airlines.

Calling it “Safety Club” would be missing the point (and not sound as much fun). We’re not here to blather on about SMS, FOQA, Safety Culture, or even CRM: we want to get right to the core of it and discuss the dangers – hence, Danger Club.

What happens at Danger Club?

We get together as pilots, we look at one specific incident or accident, and have a conversation about what went wrong, and see what we can learn from digging into it. We’ll host it on Zoom, chat for an hour or so, and decide together what’s useful to talk about and how we can make the next one better.

OPSGROUP members – keep an eye on the Danger Club forum page for details of the next event.

Who controls you?

Who controls you?

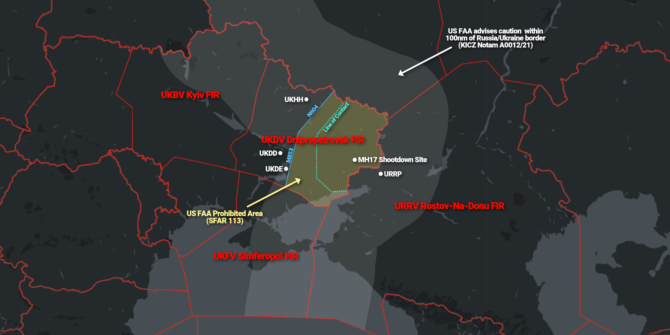

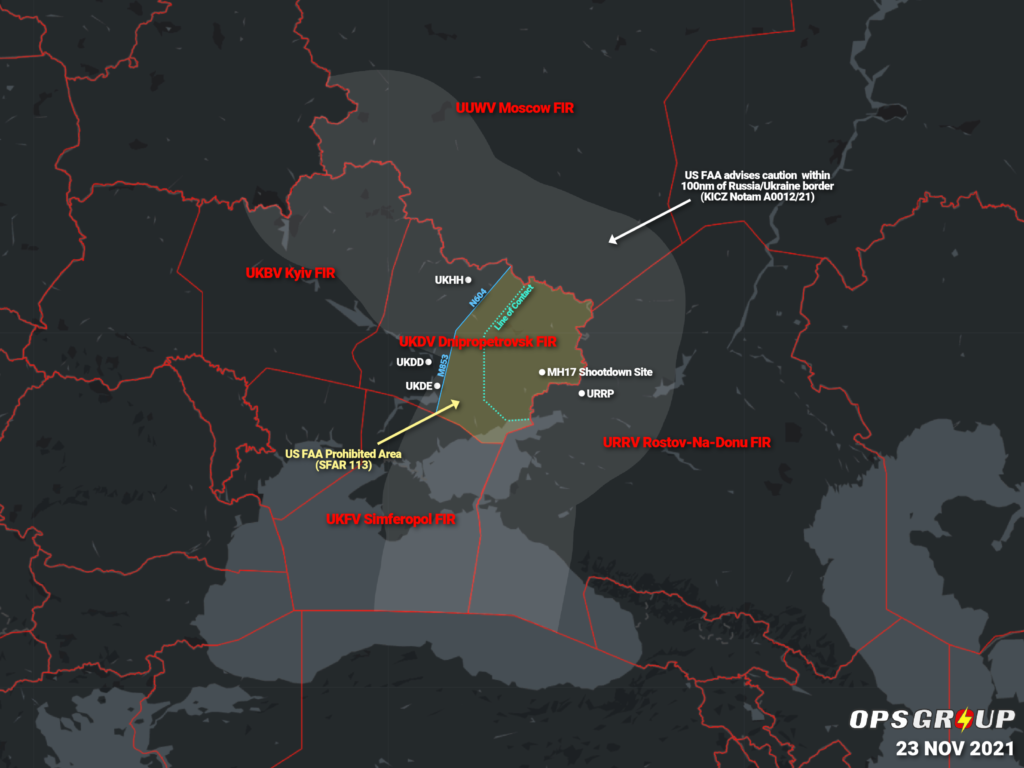

The FAA warned of

The FAA warned of

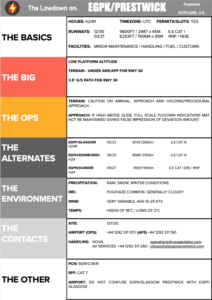

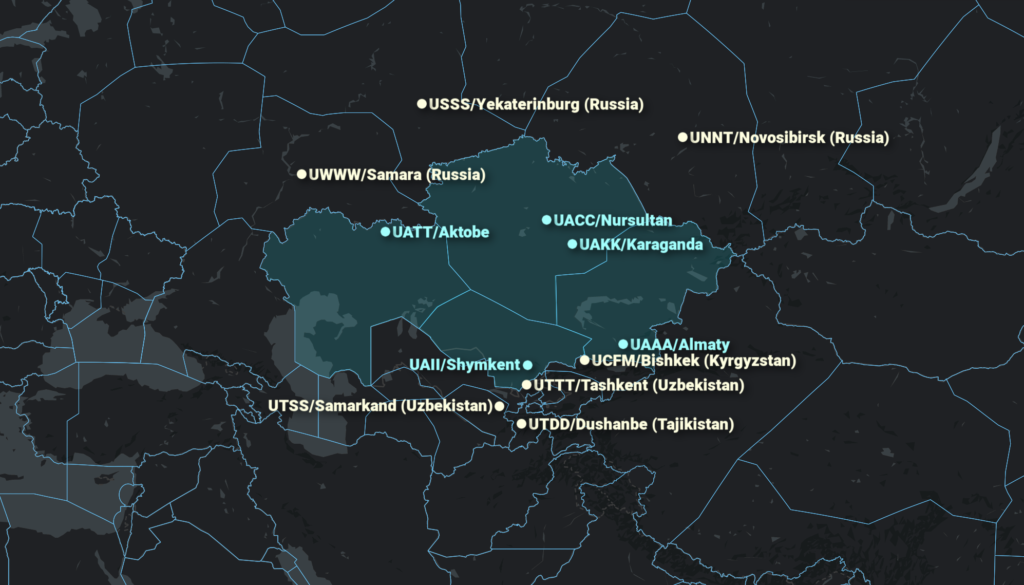

Fuel is still being provided to commercial flights and some charters on KZ registered aircraft, but foreign registered non-scheduled flights should tanker fuel inbound.

Fuel is still being provided to commercial flights and some charters on KZ registered aircraft, but foreign registered non-scheduled flights should tanker fuel inbound.

Unfortunately, sometimes folk

Unfortunately, sometimes folk