Every so often, a question drops into our inbox that reminds us just how big and how quiet parts of the world still are.

Not long ago, someone asked about flying from Australia to the southern tip of Argentina. It’s a trip across one of the most isolated parts of the planet: long stretches of ocean, few places to land, and very little room for error if something changes. There isn’t much written about it, and only a small number of crews have done it.

We checked with the OPSGROUP community and heard back from several operators and trip support teams who have made the crossing. They shared where they routed, where they stopped, and what they learned along the way.

This short guide brings together what we know so far, and we’ll keep adding to it as more of you share your experiences. If you’ve flown anywhere in this region, we’d love to hear from you at team@ops.group.

Few Places to Land

Once you leave Australia and head east across the South Pacific, things get quiet very quickly. It is a huge region with many small nations and islands, but only a few airports have long enough runways and operate around the clock. Many smaller fields have little or no parking, and fuel is not always guaranteed. Communication can also be slow, as email exchanges with local FBOs or authorities often take time, so it helps to plan well ahead.

Finding suitable alternates is another key challenge. Distances between usable airports are long, and ETOPS planning can be complex. Some crews recommend keeping about five degrees of spacing between waypoints to make navigation and decision-making easier. There are also a few US military airfields in the region, such as PGUA/Guam and PKWA/Kwajalein, but these are not open to civilian traffic.

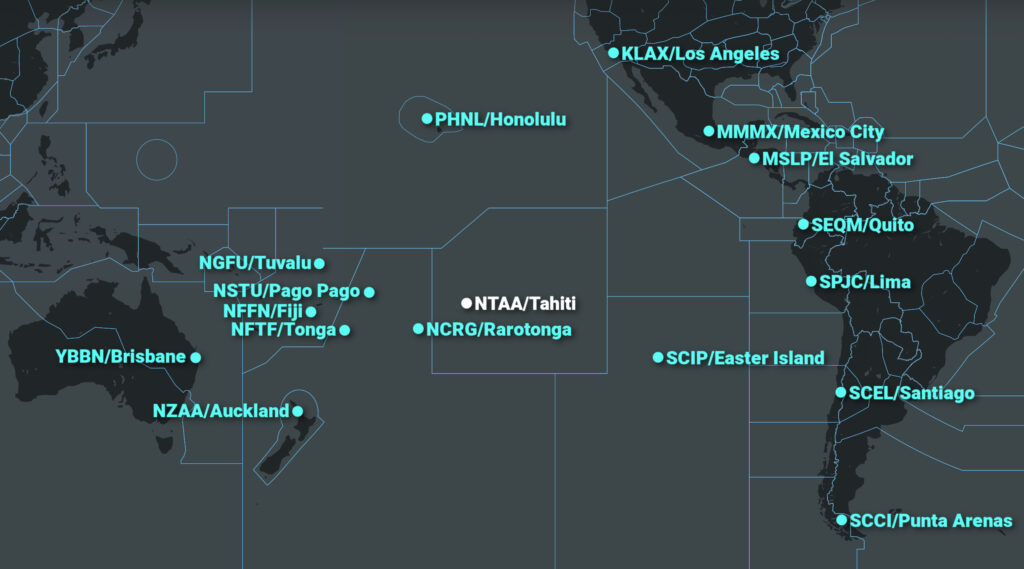

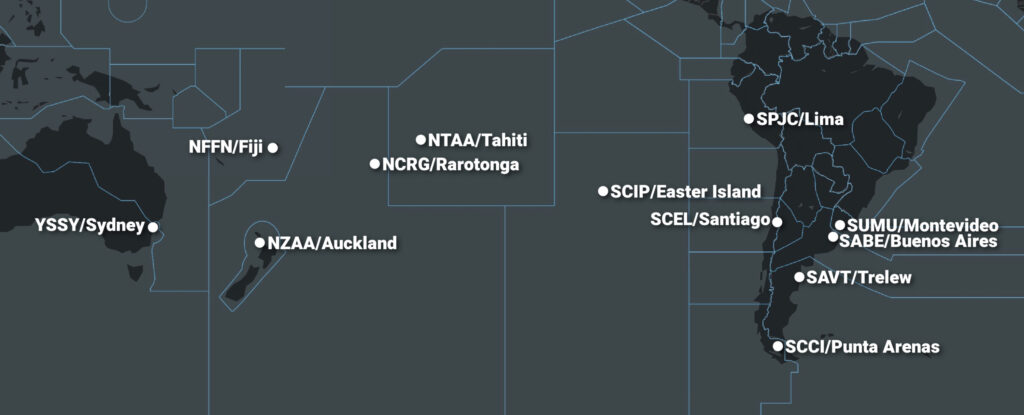

SCIP/Easter Island is the only true mid-ocean option. To the west lies NZAA/Auckland, and to the east SCCI/Punta Arenas marks the entry into South America. Antarctica may look close on a map, but it is not a realistic option because there is no fuel or services, and diversions there are reserved for real emergencies.

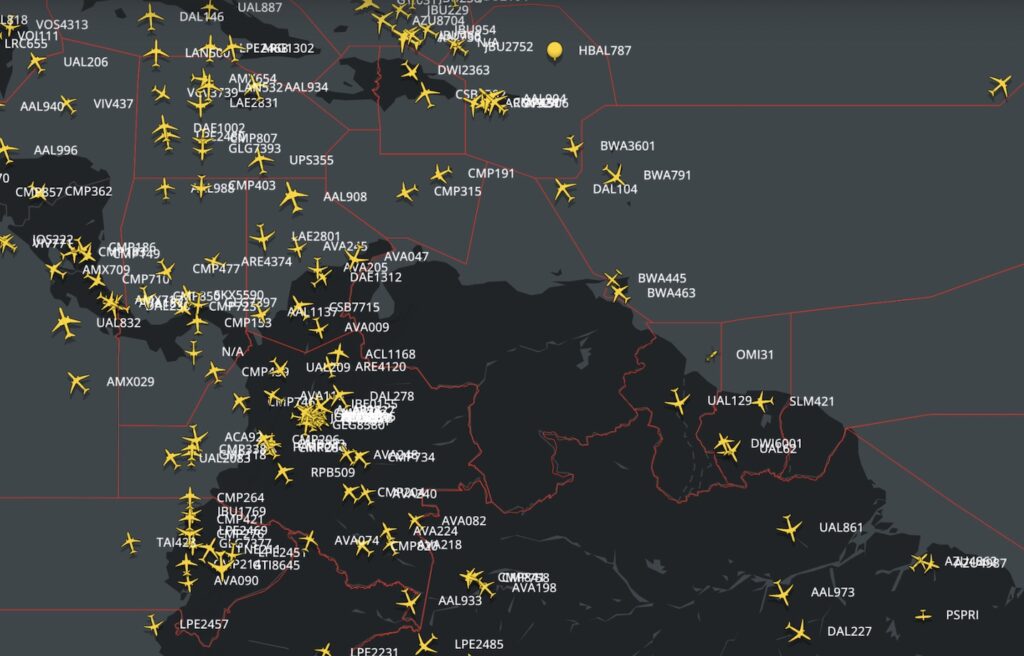

Most operators who have crossed the Pacific follow a similar island-hopping route:

YSSY/Sydney → NTAA/Tahiti → SCIP/Easter Island → South America (SADF, SCCI, SUMU)

Trans-polar routing is not practical for most bizjets, so this Polynesian path remains the preferred choice.

Many of the islands that can handle larger bizjets are not open 24 hours and often require slots or PPR. Last-minute diversions are rarely possible, especially in Polynesia. Even the main stops such as NTAA/Tahiti and SCIP/Easter Island can face full airport or runway closures at times. On Easter Island, handling is provided by a single agent with limited services, and cash may be preferred. Other alternates, including NCRG/Rarotonga, have similarly tight hours, so it’s best to check schedules and requirements well in advance.

Fuel shortages are uncommon (except for NCRG/Rarotonga, which has one now and then when the fuel tanker is late to arrive at the island), but arranging fuel releases in advance is always sensible. Permits and visas can also take extra time depending on the country, so it helps to build that into your schedule.

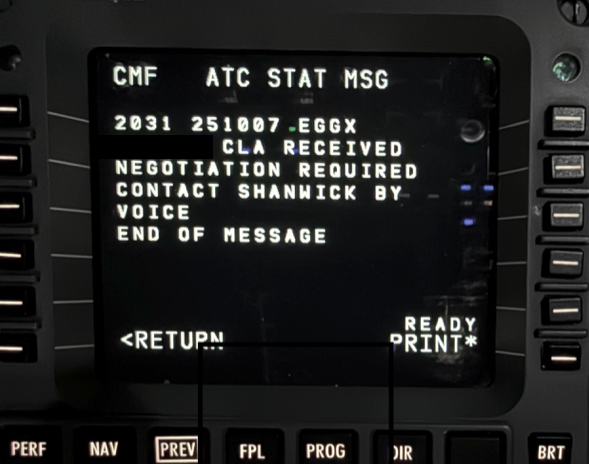

Comms and datalink are generally reliable, although one crew reported a four-hour satellite internet dropout west of Easter Island. Light turbulence can occur in the low 40s, especially during the Southern Hemisphere winter.

Once you reach the mainland, things become much easier. Handling in Chile and Argentina is efficient, fuel is reliable, and services are good. On the islands, operations are simpler but still manageable with good coordination.

How different aircraft made the trip

Several long-range bizjets have flown this route. Here are examples of routings that worked in practice.

Challenger 350

SADF/San Fernando → SCIP/Easter Island → NTAA/Tahiti

NTAA/Tahiti → SCIP/Easter Island → SADF/San Fernando

Possible with careful planning around alternates and timing.

Falcon 7X

SABE/Buenos Aires → SCIP/Easter Island → NZAA/Auckland

YSSY/Sydney → NTAA/Tahiti → SABE/Buenos Aires

SADF/San Fernando → SCIP/Easter Island → NFFN/Nadi

NFFN/Nadi → SCIP/Easter Island → SADF/San Fernando

A flexible option with enough range to connect Polynesia with South America comfortably.

Global Express

SAVT/Trelew → NFFN/Nadi

Has no trouble with the longer Pacific legs, and Fiji works well as a fuel stop.

Gulfstream G550/G650

YSSY/Sydney → NTAA/Tahiti → SADF/San Fernando, SCCI/Punta Arenas

A straightforward option via Tahiti that keeps legs comfortable.

Airports along the way

A quick look at the key tech-stops, listed east to west, from Australia/New Zealand toward South America.

🇦🇺 YSSY/Sydney – Australia

The airport runs H24, though there is a strict 2300-0600 LT curfew. Handlers can request exceptions, but these are not guaranteed. FBOs can usually arrange CIQ directly on site. Fuel is tanker only, so plan large uplifts in advance. Slots are required. Expect standard Australian disinsection rules and have the empty spray can ready on arrival.

Jet Aviation closed its doors permanently on Nov 30, so ExecuJet is now the only FBO at the field moving forward.

FBO contact: fbo.yssy@execujet.com

🇳🇿 NZAA/Auckland – New Zealand

Another solid H24 tech stop just across the Tasman. The airport stays open all day, with short runway maintenance early on Monday and Saturday from 0130-0430 LT, which sometimes does not appear in Notams. Private flights under Part 91 do not need permits, while charter flights under Part 135 require CAA approval. CIQ operates around the clock, and fuel is available with notice, although last-minute uplifts can be slow during busy hours. New Zealand enforces strict biosecurity, and cabin disinsection is mandatory, but quarantine staff can handle it on arrival if needed.

FBO contact: fbo.nzaa@execujet.com, anz_info.s.e.a@swissport.com

🇫🇯 NFFN/Nadi – Fiji

A smooth 24-hour tech stop and refuel point midway between Polynesia and South America. The airport and customs run H24, fuel and handling are reliable, and turnarounds are quick. Wildlife can be active at dawn and dusk, but otherwise ops are straightforward.

FBO contact: info@fijiairports.com.fj, fbo@ats.com.fj

🇵🇫 NTAA/Tahiti – French Polynesia

The only international airport in French Polynesia and the main South Pacific stop. NTAA runs H24, though through early February non-based BizAv (private and charter flights) face limited operating windows matching airline peaks. Movements in those periods need airport manager approval, and use as a diversion is restricted to locally based or pre-scheduled aircraft.

For example, TASC FBO confirmed full 24/7 support on the north side, including CIQ pre-clearance on arrival. They handle disinsection if needed and provide fuel exclusively under the Petropol ExxonMobil brand. Occasionally, filing flight plans through the ARO can be difficult, so it’s recommended to send the FPL by email to seac-pf-bria-bf@aviation-civile.gouv.fr and wait for confirmation.

Landing permits must be requested by operators via the French Polynesia CAA portal (72 hours for private flights, 14 days for charter). Nearby NTTB/Bora Bora and NTTR/Raiatea are domestic with limited hours and fuel, making NTAA the only reliable international option in the region.

For details on current NTAA restrictions and seasonal procedures, see our dedicated article here.

FBO contact: nuutea@tascfbo.com, ops.ei@airtahiti.pf, ulric.allard@airtahiti.pf

🇨🇰 NCRG/Rarotonga – Cook Islands

A small but reliable entry point between French Polynesia and South America. ATC hours rotate and are published by Notam, with controllers available on request for diversions at +682 25890 or +682 71439. A landing permit is required about 14 days in advance via the CAA, and CIQ is available anytime by prior arrangement. Most nationalities receive a 30-day visa on arrival. Fuel is supplied by Pacific Energy and currently limited for non-scheduled flights. There are two international stands, and overnight parking requires a towbar.

FBO contact: ross.warwick@airraro.com, savage@airportauthority.gov.ck, nikautangaroa@airportauthority.gov.ck

🇨🇱 SCIP/Easter Island – Chile

A key mid-Pacific stop that works well for fuel and rest but needs careful planning. The airport operates roughly 0900-1700 LT on weekdays with shorter weekend hours. A landing permit is required, and once approved, it also serves as parking authorization. Fuel from WFS must be requested 24 hours in advance, and all arrivals must complete cabin disinsection and show the empty spray can as proof. Instrument approaches are often unavailable by Notam, so be ready for visual arrivals and plan alternates carefully. Parking is very limited, usually one stand overnight, and the single handler provides basic services, often accepting only cash.

FBO contact: punavai949@gmail.com, edmundserviceseirl@gmail.com

🇨🇱 SCCI/Punta Arenas – Chile

A reliable southern mainland stop. The airport operates H24 with full CIQ coverage. Three runways provide flexibility, the main one being RWY 07/25 (2790 m / 9154 ft). Fuel is available, and parking can be arranged but must be requested in advance due to limited capacity. No slot requirement.

FBO contact: fbo@aviasur.com, ygonzalez@aviasur.com

🇨🇱 SCEL/Santiago – Chile

Another entry point into South America with reliable services and straightforward procedures. The airport operates H24 with CIQ available around the clock. Parking for BizAv is generally available, fuel is offered H24, and there are no slot or PPR requirements.

FBO contact: fbo@aviasur.com, psaavedra@aviasur.com

🇦🇷 SABE/Buenos Aires – Argentina

FBO contact: comercial@royalclass.global, info@royalclass.com.ar

🇦🇷 SADF/San Fernando – Argentina

The other BizAv option for Buenos Aires. H24 with no slots, customs available, easy parking, and fuel on site. The single runway 05/23 is shorter at 1690 m (5545 ft), but ops are smooth, making it a popular alternative to SABE.

FBO contact: fbo@flyzar.com

🇦🇷 SAVT/Trelew – Argentina

A useful southern stop when routing toward Patagonia or Chile. The airport is open H24 with fuel available, and customs work on request with a 48-hour PPR, so it’s best to plan ahead to make sure everything is ready on arrival.

FBO contact: ops@aerowise.aero

🇺🇾 SUMU/Montevideo – Uruguay

A solid H24 option for tech stops or entry into Uruguay. The airport offers full customs, long runways, and reliable support, though most parking stands have specific wingspan and pushback limits, so it’s best to confirm space in advance. Fuel is available. Note local noise restrictions prohibiting departures over Montevideo between 2100-0700 LT, except for emergencies or weather-related operations.

FBO contact: fbo@fbo.com.uy, ops@aerowise.aero

Flying between Australia and Argentina is very doable, just not the kind of trip you improvise! The distances are huge, the alternates are few, and every good piece of info makes a real difference.

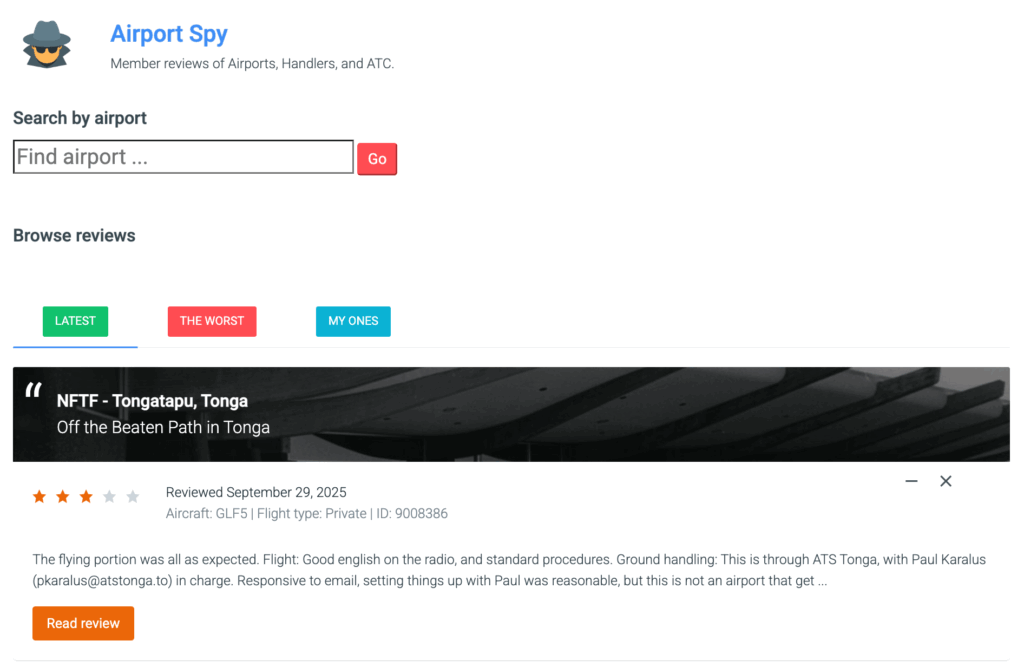

If you’ve been through any of these airports recently, we’d love to hear your story. You can share it with the community by submitting an Airport Spy Report. It’s basically a little postcard about what happened on the ground so the next crew knows what to expect. Your notes help everyone who sets out across the quiet South.

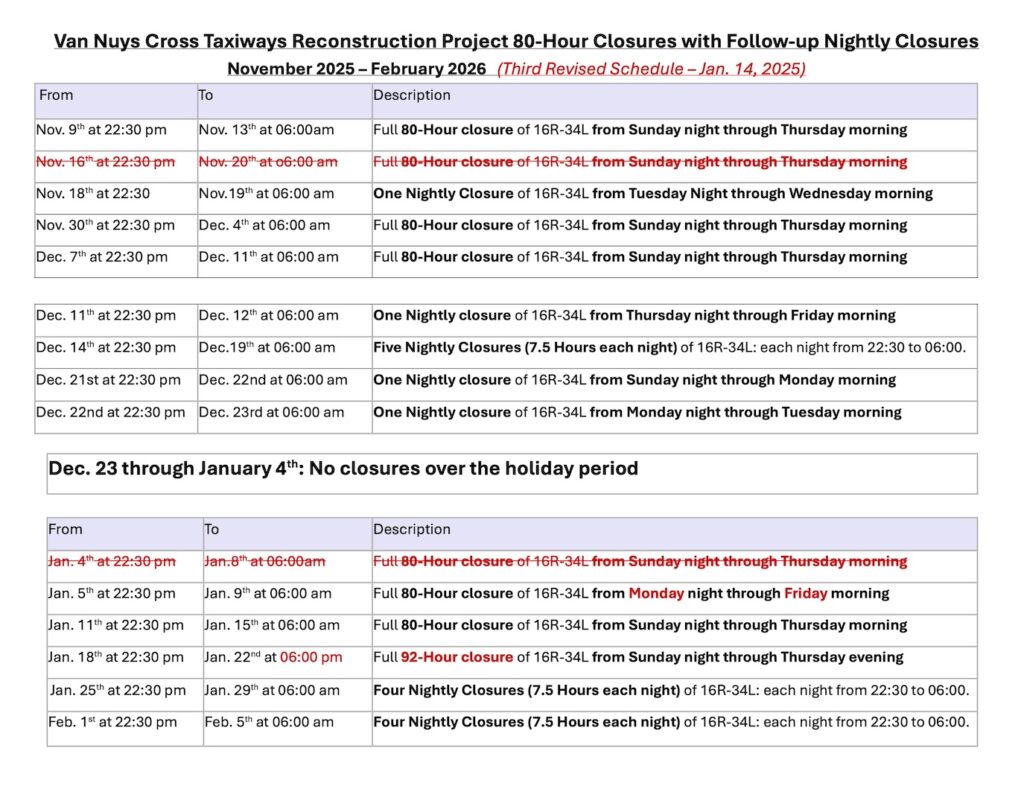

Those big 80-hour closure blocks are the ones to really watch out for. They start Sundays at 2230 and end Thursdays at 0600 local time, so the runway is effectively unavailable all day Mon/Tue/Wed during those periods. You can check the

Those big 80-hour closure blocks are the ones to really watch out for. They start Sundays at 2230 and end Thursdays at 0600 local time, so the runway is effectively unavailable all day Mon/Tue/Wed during those periods. You can check the