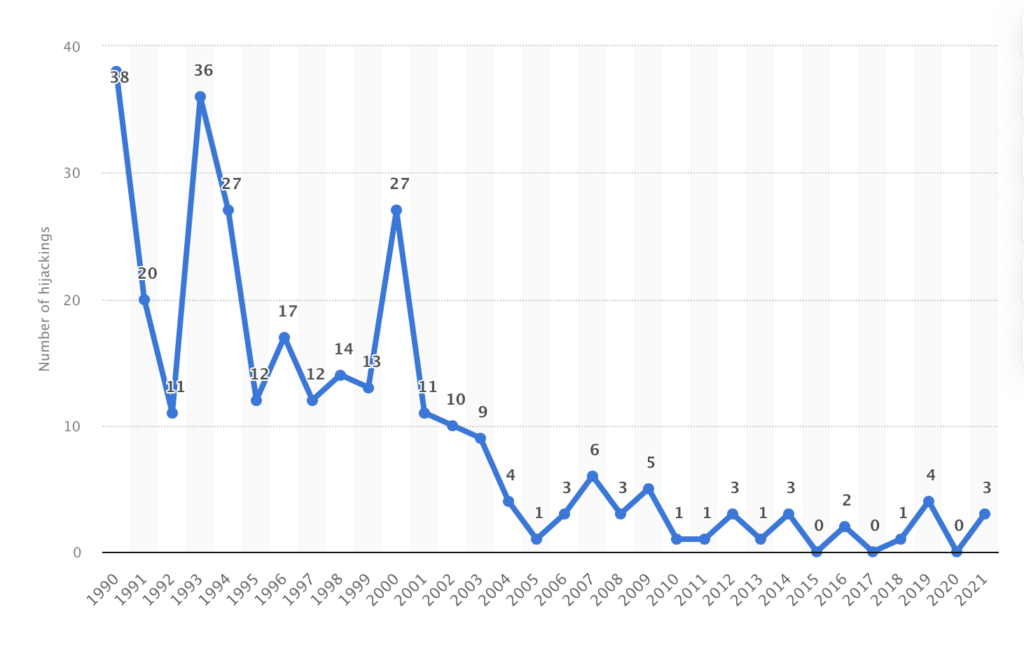

Attempted hijackings of major airlines have decreased because of big advances in security and safety.

But, reports of an apparent attempt on an Emirates aircraft surfaced on November 10, so we thought we would take a look at those security procedures, ops procedures and some FAA door related news, to help you stay safe in the skies.

The ‘was it a hijack attempt?’ reports.

Look, we don’t know, and we aren’t into speculation.

All we’ve seen is a bunch of news sites saying a 777 was diverted back to Athens after taking off for New York, possibly accompanied by F-16s, possibly with reports of a possible suspect onboard, possibly under a ‘Code Renegade’.

It landed safely, and there will likely be detailed reports out about it at some point so we are going to leave it there.

Hijack attempts are not common anymore, mainly because security procedures have been developed so much to help prevent them.

1990-2021 hijackings graph.

But we don’t want to get complacent about it, because most of those procedures fall on us (the operators and the air crew).

So we figured a recap on what some of these procedures are, and what it might mean for you ops-wise could be handy.

On the ground

Security stuff starts on the ground. Actually it hopefully (if the systems work) should start and also end here.

If you’re up for a lengthy read, then check out the minutes of a major meeting which took place 10 years after Sep 11th (in 2011, so over ten years ago now) on changes to TSA procedures and processes. Here they are. Read away.

Basically, there are A LOT of procedures and processes for ensuring only ‘good’ passengers get on airplanes, and a lot of this lies in the Customs systems that are now in place.

We are going to be super lazy here and say ‘go read this NBAA post’ if you have questions on the specifics of customs and regulations stuff. It’s a big old topic and all we’re really trying to do here is say “make sure you get the customs bit right” (not actually tell you how to).

*But if you do have questions, let us know and we’ll root out some answers for you.

- In general, if you’re a big airline or commercial operator, a lot of this is going to be done for you at the airport

- If you’re a private or business jet operator (that doesn’t just fly the owner around) then you might need to do some more checks yourself (or more stuff to ensure you’re compliant with required security and document checking regulations).

Here are some vaguely helpful links:

- The US CBP website is filled with info on all things US Customs and Bordery, along with a bunch of info on things to help speed up the process for pax.

- Your US pre-clearance airports are listed here, along with info on that.

- For international folk arriving into the US, you might want to look at APIS (Advance Passenger Information System Manifest) Transmissions if you don’t already know what these are.

- There are fairly hefty fines for the PIC of a private aircraft if you don’t follow the US regulations. If you have any questions, try these folk – GAsupport@cbp.dhs.gov

- There is some CANPASS info here for if you want to fly to Canada.

- There is some ETIAS info here for those of you planning trips to Europe.

Biman hijack attempt, 2019.

In the air

Let’s jump right in with some regulatory stuff:

The US, UK, Europe (and a fair few other places) have fairly strict procedures in place for who can sit in the flight deck jump seat. This doesn’t just apply to aircraft registered in whichever place either. If you are operating into their airspace you probably still need to be thinking about this.

And we’re talking about what the authorities say, not what your company says. This might be stricter (so check that out for yourself).

The basic rule for most places is that during the flight anyone in the flight deck needs to be authorised to be in the flight deck.

What this means can vary though.

In the UK for example, only members of the operating crew (the pilots actually flying the thing on that flight) may be in there. No supernumerary crew. No pilots who work for the company, have that type rating, but are just positioning.

There are other authorised folk too:

- Like an aviation authority air carrier inspector.

- A DOD commercial air carrier evaluator.

- An ATC person (but only if authorised by the administrator, and only so they can observe ATC procedures).

You know what, rather than us writing it all out:

- Go look here for the FAA stuff.

- You can try here for the UK CAA stuff.

- And here for EASA (Europe) regs.

Remember German Wings?

The German Wings event brought in a bunch of big new regulations in the EU. The main ones being:

- Regulation 175 which requires airlines ensure all pilots receive a psychometric evaluation within 24 months of employment and before they start their line flying

- A requirement to always have more than one person in the flight deck

The second one was problematic. It added an extra layer of hassle when pilots needed to leave the flight deck to use the toilet, (and an added layer of embarrassment when you’ve had to ask for the fourth time in under an hour). This has been removed and is now just a requirement within certain operator policies, rather than a state or authority requirement.

Not letting random passengers in, in flight, is still a thing though. As is looking after the well-being and mental resilience of your crew and colleagues.

The FAA Flight deck barrier policy.

September 11th brought about a new focus on flight deck security. Namely, folk can no longer fly with their doors open, and access must be controlled. This applies to commercial aircraft, it may not apply to your private aircraft.

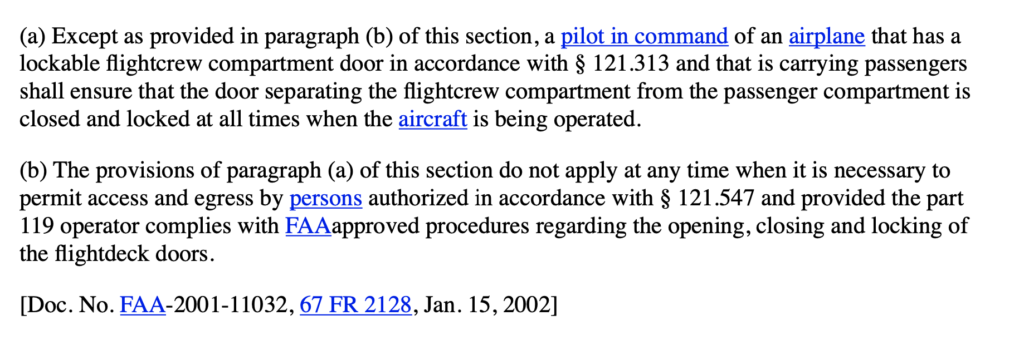

So, for those it does definitely apply to – a secured door with an access code, or a secure access procedure is required. This is covered in § 121.587 Closing and locking of flightcrew compartment door and says:

Recently, the FAA have recently published a new thing on flight deck door barriers. Something the likes of ALPA have been asking for since 9/11.

Recently, the FAA have recently published a new thing on flight deck door barriers. Something the likes of ALPA have been asking for since 9/11.

The summary is that it will apply to “certain airplanes used to conduct domestic, flag, or supplemental passenger-carrying operations”. This won’t apply to Part 129 (which is foreign operators heading into the US, or US registered ones that only operate outside the US).

The ‘secondary barrier’ creates an extra level of security by requiring that, prior to the flight deck door being opened, this must be secured shut like a sort of cattle gate.

Secondary barrier.

Knock knock. Who’s there? Jack!

If you do have a hijacker onboard then remember three things:

- Don’t open the flight deck door

- Don’t open the flight deck door!

- Do squawk 7500

If you don’t want ATC thinking you have a hijacker onboard:

At any point in flight, (sort of goes without saying, but we’ll say it anyway), maintain good radio communication.

There are a lot of ADIZ (military airspaces) out there where you must check in, in advance. There are also a lot of conflicts going on which mean countries are particularly cautious when it comes to aircraft not in contact with who they should be in contact with.

If you don’t want some F16s to come swooping up alongside you then:

- Don’t miss radio calls.

- Do check in (in advance) if the airspace requires you to.

- Do try other systems or get relays if you lose contact.

- Don’t accidentally stray into airspace you aren’t cleared to fly into.

And if you don’t have an attempted hijacking going on then definitely don’t do what a South African crew accidentally did in 2016, or what a 747 crew for a major US airline did in 1999. You read about those embarrassing incidents here.

More reading:

- Latest: FAA Warns on Runway Length Data and Overrun Risk

- Latest: EASA’s New Cyber and Data Risk Rule for Operators in Europe

- Latest: Airport Spy: Real World Reports from Crews

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly