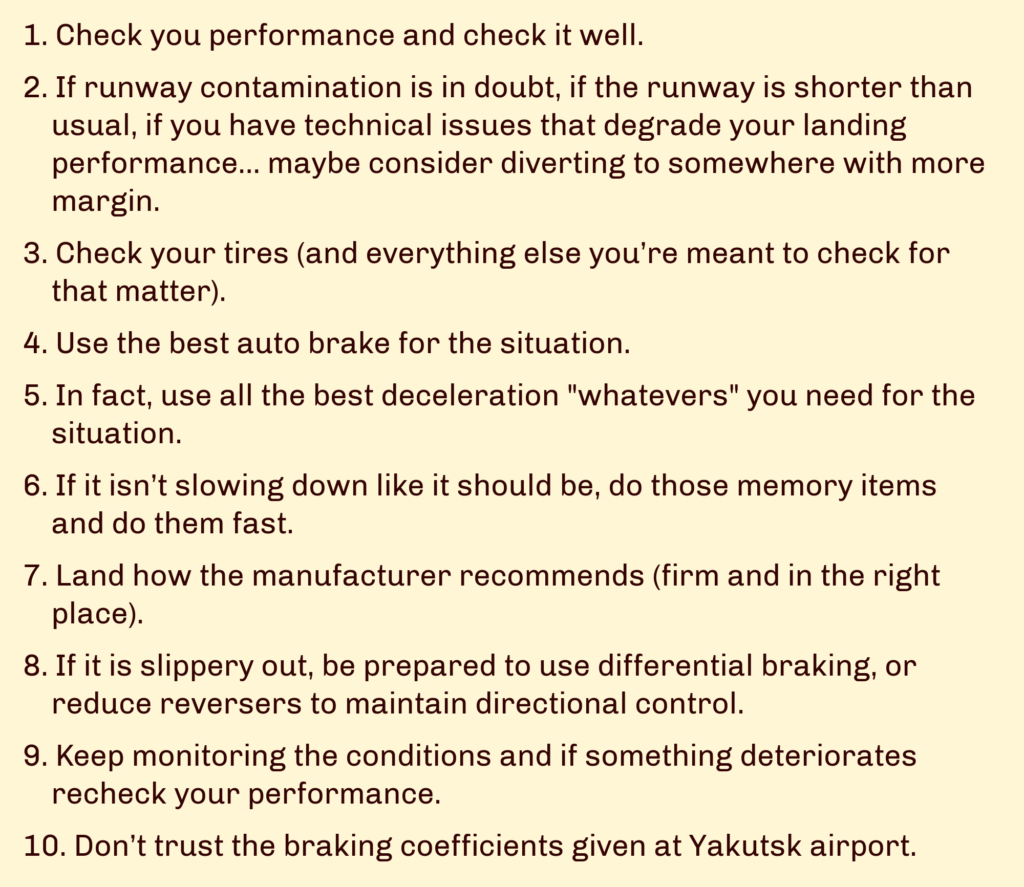

Canada, the (often) cold and (parts of it) remote northern neighbour to the US.

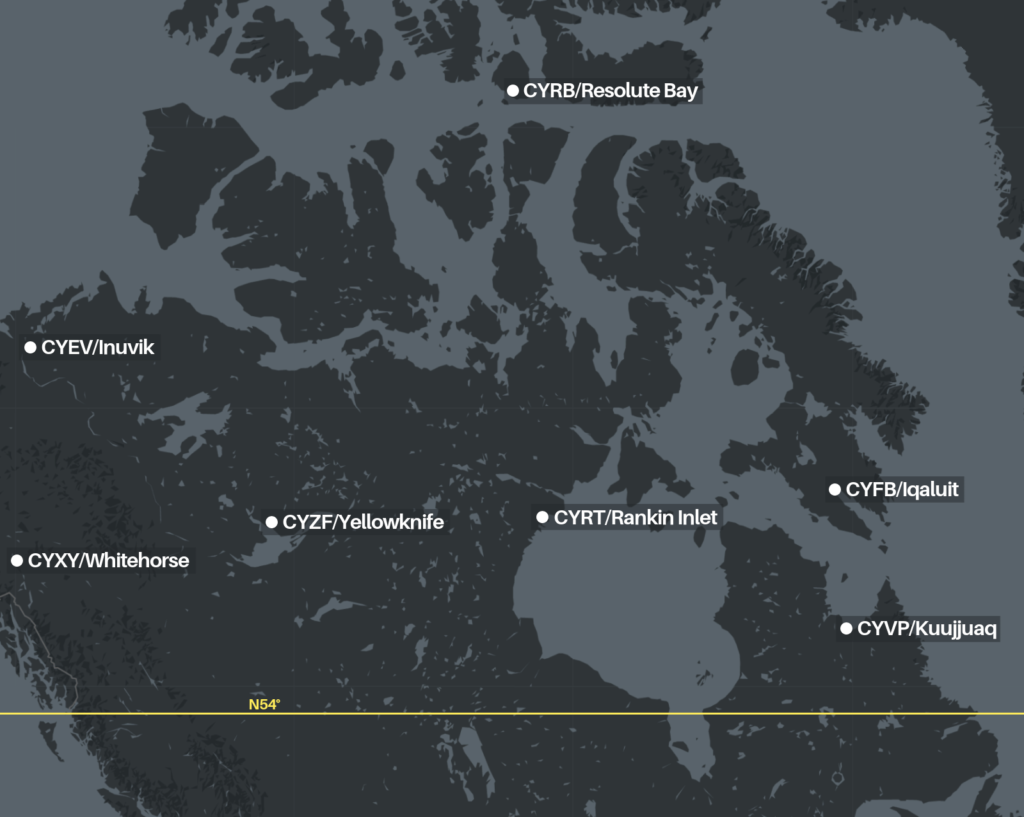

We thought we would take a little look at what is available out there, should you find yourself anywhere north of Highway 16 (above N54°).

Why N54°?

Well, because there is not much north of it. Or rather, there is a whole lot of country but not many options north of it. The main cities (and airports) in Canada are primarily in the southern region, close to the US/Canada border.

Here is a picture, because a picture speaks a thousand words. Or in this case, speaks about 10 airports…

The main Canadian airports are mainly along the southern border.

Canada is big. Very big. And the main airports (big international ones) are generally all situated below N54°. There are others out there though. The most northerly airport which receives scheduled passenger airlines services is CYRB/Resolute Bay sitting right up at N74°.

Unless you are actually operating into somewhere in the outer fringes of Canada then it is unlikely you will be routing over this region. Most polar routes bring you down across central eastern Canada and are unlikely to go so far west for the very reason there are very few airports available there if you need them.

The airports to consider above N54°.

CYRB/Resolute Bay

This has a 6504’ runway 17/35 (that’s orientated to True North, FYI). Watch out though – it’s a gravel runway, so only really useful in a dire emergency!

There is an ILS to runway 35, an RNAV (GNSS) for runway 17, and a warning for severe turbulence during strong easterly winds. Probably something to do with the airport sitting on the edge of a craggy outcrop with lumpy, bumpy terrain to its east. Aside from the (cold) weather warnings, this airport also suffers from WAAS outages.

CYFB/Iqaluit

If you are up as high as this, and around the eastern region, you are probably better checking out CYFB/Iqaluit. This is often used as a planning airport for en-route diversions during polar and northerly North Atlantic crossings.

Runway 16/34 is 8605’ with an ILS to 34 and an RNAV to 16. Land on 16 and you have a few nice runway exits. Land on 34 and you’ll be doing a 180. It is an RFF 5.

There are a lot of ‘CAUTION’ notes on the airport chart here. Caution a steady green laser light, radiosonde balloons, terrain near the airport, large animals, wind that swings all over the place, a nearby blasting area, a random 2.5° ILS slope…

When the wind is from the north you can expect ok weather, if it is from the south the weather is less good, and this is particularly the case in Spring and Fall.

The charts suggest limited winter maintenance, but folk who have operated there say the maintenance is good.

So this is a good airport for emergencies, but has challenges of its own.

The main FBO is Frobisher Bay Touchdown Services who you can reach on +1 867 979 6226 / land@cyfb.ca / 123.350

CYVP/Kuujjuaq

Another eastern option. Runway 07/25 is 6000’ with an ILS to 07 and an RNAV to 25, and a VOR backup. There is a second gravel runway 13/31 which is 5001’.

The challenging environment means there are a few gotchas here too. Runway 07/25 has poor drainage and there is a risk of hydroplaning. It also has large animals in the airport perimeter (not sure if this means moose, bears or polar bears. Probably Caribou though), radiosonde balloons and seaplane activity on a nearby lake.

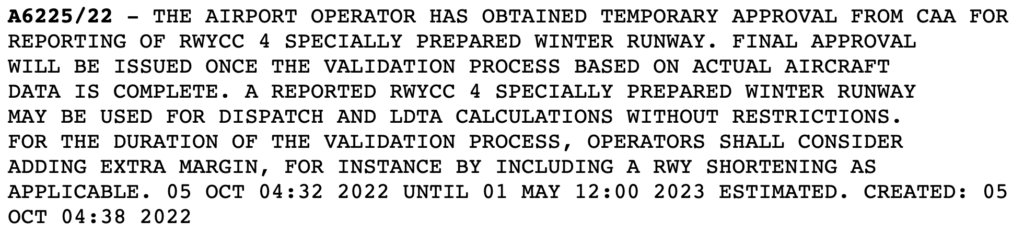

Might have been in Alaska

They say winter maintenance is limited, but this is because they do not operate 24/7. A few hours notice and they can clear the runway, and be available if needed though.

Talk to Halutik Enterprises if you are planning on planning this airport +1 819 964 2978 / cgadbois@makivik.org or try the airport direct on +1 819 964 2968 / 122.2

So CYFB/Iqaluit and CYVP/Kuujjuaq are your only paved runway options to the east.

CYRT/Rankin Inlet

The only paved runway in the central region, this offers a 6000’ runway 13/31. Both approaches are RNAV (GNSS) and orientated to True North.

There isn’t much info on Rankin Inlet, but given the remoteness of the region you can probably assume limited ground support and harsh winter conditions but actually the services are very good and those harsh conditions are limited to the winter! Winds are a bit of an issue here at times – expect some strong, gusty crosswinds.

Check out the picture below…

The only FBO is the airport operator who you can reach on +1 867 645 2773 / +1 867 645 8200. yrtmaintainer@gmail.com might work too.

Good luck spotting that runway when it is covered in snow

CYEV/Inuvik Mike Zubko

You have three paved options to the west.

First up, Mike Zubko. Mike, in case you’re wondering at the name, was a local aviator of note. Originally from Poland, he emigrated to Canada, became an Engineer with Canadian Pacific Airlines and went on to set up the Aklavik Flying Service, serving the remote region of the northwest corner of the North West Territories.

Anyway, the airport of his name has a 6001’ runway 06/25 with an ILS for 06 and an RNAV for 24. There are ‘limited graded areas’ outside the runway area here which basically means stay in the runway and you’re good.

Good ol’ Mike Z

CYZF/Yellowknife

You will find two runways here – 10/28 5001’ with RNAV (RNP) approaches and 16/34 7503’ and offering an ILS to 34, or an RNAV (RNP). It is an RFF6 with 2 vehicles on call.

Yellowknife has limited winter maintenance (because of those operating hours again) and extensive bird activity but is a major hub in the area and will be able to provide ground support for most aircraft.

CYXY/Whitehorse

The biggest of the three, there are three runways here although 14R/32L at 9500’ and 14L/34R at 5317’ are the only two long enough for anything bigger than a short field Canadian Goose landing. 32L has an ILS, 14R has an RNAV. And actually there are no published approaches for 14L/32R let alone 02/20. This is an RFF5.

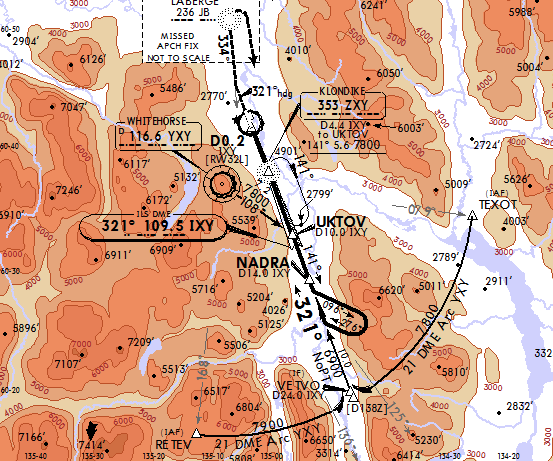

This airport is right in the middle of some pretty challenging terrain. Loads of it with an MSA rising up to 8500’ in the south. So you can expect some mean winds and a fairly challenging approach, missed approach and departure procedures.

Lots of terrain

And we’ve been told about some others…

CYYQ/Churchill in the shores of Hudson Bay. The airport is not open 24 hours, but does boast a 9195′ runway with an ILS to 33 and an RNAV to 15.

This airport might look relatively small, but it sees high traffic numbers as the area is famed for ecotourism (great polar bear sightings) and it is also a primary transit hub for people and cargo travelling between Manitoba and the more remote regions. It can accept emergency diversions from up to Boeing 777 and 747 aircraft so a good option.

CYMM/Fort McMurray is a nice central international airport in Alberta used as a destination for narrow body aircraft, but a decent alternate for wide body aircraft with its 7503′ runway and ILS approach.

CYPR/Prince Rupert in BC has a 6000′ runway, and RNAV approach. There is limited taxiway and apron space here so a good emergency or diversion airport, but not much other support available and it has “limited winter maintenance”. The airport is on an island and weather observation is not done at the field so caution using this in poor weather.

CYXJ/Fort St. John also known as North Peace Regional is another BC airport option for emergency diversions. It has an unusual crossed runway layout, with 6909′ and 6698′ lengths. Runway 30 has an ILS, otherwise you’re looking at an RNAV. This airport is also slightly higher elevation, sitting at 2280′.

CYXT/Northwest Terrace Regional has Dash-8 sized aircraft operating in. It offers a 7497′ runway with an ILS and a shorter 5371′ runway with RNAV approaches.There is high terrain here (the airport is in a valley) and it is not recommended to use unless familiar with the airport, and even then only during daylight hours.

That’s your lot!

Unless someone knows about one we haven’t heard of? If you have, please share. Email us at news@ops.group. Someone, somewhere, someday might be out in the great Canadian wilderness in need of an airport.

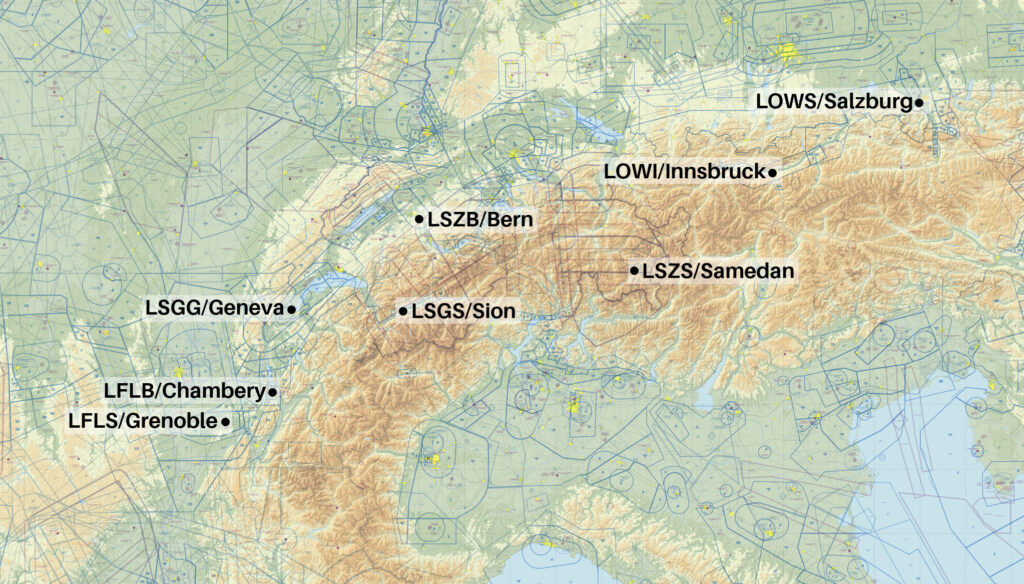

Innsbruck – Austria

Innsbruck – Austria