The Transportation Safety Board of Canada released its Watchlist for 2022, highlighting what they think the bigs and the bads to look at in the industry are. We figured it would be a lot of specifically Canadian things like grizzly bears on runways, and whether a hockey stick counts as a dangerous weapon when brought on board.

Turns out that it’s all things which are globally big and bad. What’s more, now the Covid stuff has (mostly) gone away (you might remember the whole pulling airplanes out of storage and finding bugs nesting in them fear), these are big, bad things which we’ve been talking about in the industry for quite some time.

So, because it’s November 2022, which is basically December, which means the year is pretty much over, we figured we’d tell you all about it.

The Highlights

Seems an odd choice of word, theirs not ours.

So, the first one on the list was something about commercial fishing safety. We aren’t sure if we have any commercial fisherfolk at Opsgroup, apologies if we do, but we don’t think so, so figured we would not pause too long on this one.

Same for railway signal indications. Not so relevant to aviation. We will say that following signals as a pilot is important though. If you don’t know your interception signals, you can swot up on them here.

4 clues. Only 3 are ones we want to talk about.

Onto the Aviation highlights

There are 5. We reckon they are going to be quite familiar:

- Runway Excursions

- Runway Incursions

- Fatigue

- Safety Management Systems

- Regulatory oversight

We’re going to ignore the last two, just because we don’t know much about them.

Runway Excursions

The biggest one. The baddest one. Aircraft going off the end of the runway. It happens way too often, and the outcome is often severe.

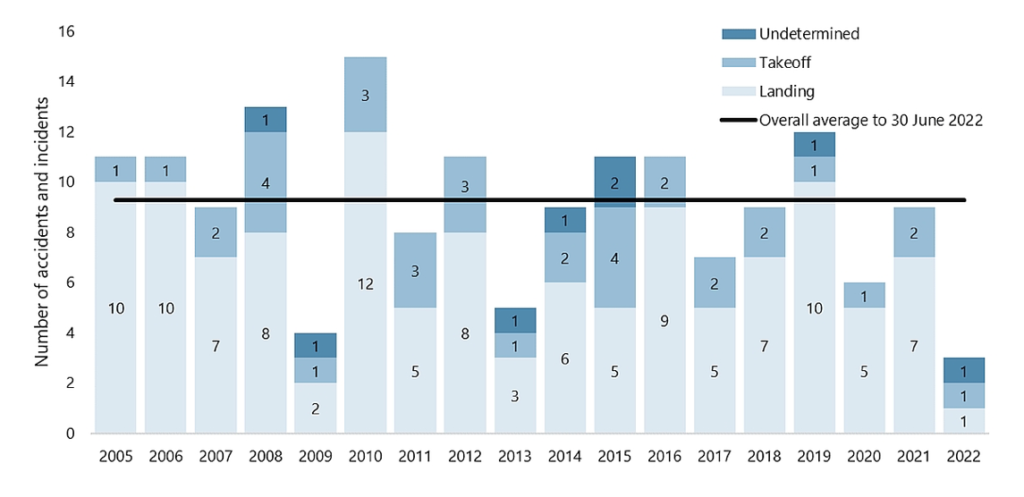

In Canada, between January 2005 and June 2022 there were on average 9.3 runway overrun occurrences per year, most of these during the landing phase.

Here’s the TSB’s graph:

This is just in Canada.

Now, they do in all fairness get some ‘overrun encouraging’ weather in the deep and distant north because it gets so cold and icy up there.

But then again this isn’t limited to Canada.

You find places all over which have strong winds (tailwinds, ballon inducing gusts…), heavy rain (slippery runways), stuff that reduces visibility on short finals (increases chances of getting unstabilised), hot and high spots (increases the ROD required), unusual terrain (increases the chances of becoming unstabilised), short runways (possible performance mishaps), or just places which are totally easy-peasy so you think it will definitely all be fine and get complacent…

Runway excursions are a global problem that don’t seem to be going away. We might have mentioned this before.

So what can we do about it?

- Know what GRF is and use it. If you haven’t heard of the (new) Global Reporting Format that came in 2021 then you can read about it here

- Use arresting systems. OK, pilots can’t really do much about whether this is available at an airport, but knowing what it is and where it is, is important because some pilots have actively swerved to avoid it. If you’re heading off a runway then that sucks but if it has EMAS then USE IT, it might save your life.

- Fly a stabilised approach. Or ask the question why you or your crew aren’t going around.

- Do performance calculations… properly. Not much else to say on that.

- Be go-around minded. Air France learned a thing or two about this in 2005 heading into CYYZ/Toronto when the weather deteriorated and they didn’t go-around. It led to a runway excursion. Read about it here if you’re not familiar with this one.

- Read this. It’s the full TSB rundown on runway overruns.

Runway Incursions

If the risk of heading off the end isn’t enough, then there is also a big risk of heading onto the runway when we shouldn’t be.

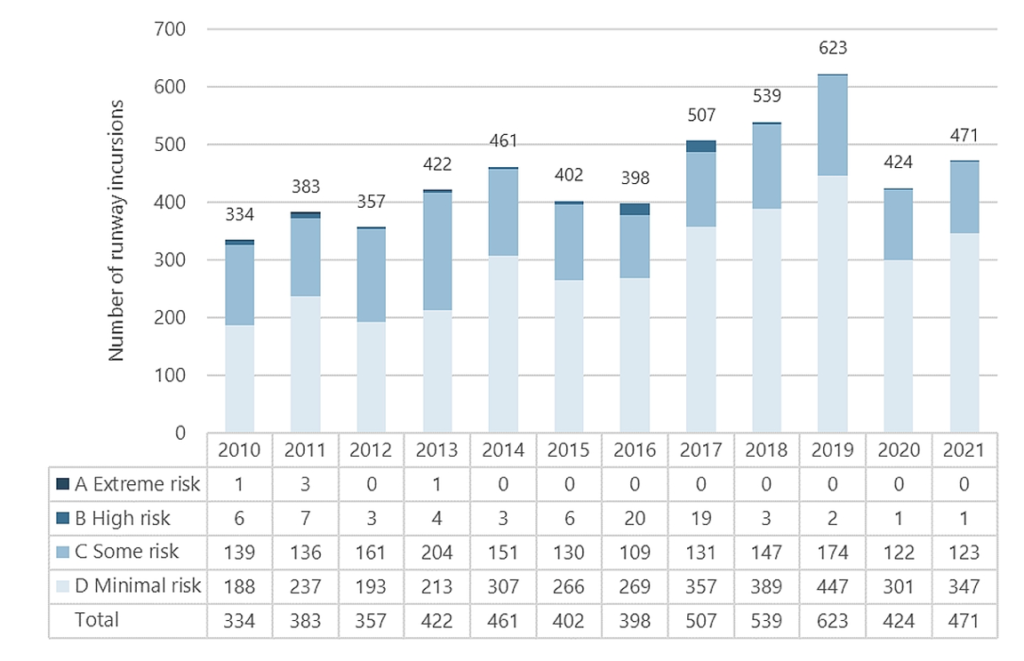

The rate has doubled in 12 years. Thankfully it hasn’t resulted in a collision, but still… not ideal.

Here’s another graph. because we like their graphs:

There are some big numbers on there.

What can we do about it?

- Know your hotspot symbols. The US have recently changed up their hotspot symbols to help with situational awareness on the taxi.

- Brief. Talk about the taxi, especially in poor visibility.

- Stop! If you ain’t sure, stop taxiing. Rolling about willy-nilly never ends well.

- Think about de-icing/anti-icing. There have been changes to HOTs in the FAA winter manual. Taking off with ice on your wings is going to make the takeoff roll hair-raising. Don’t risk it, de-ice!

- Read this. The TSB’s stuff on incursions, in full.

Fatigue

Yep. Where to start. This is a big conversation which needs to be had more in the industry. Aside from FTLs and roster patterns (a can we won’t open now), we do think there are some things which aren’t getting mentioned enough which can lead to fatigue:

- Staffing issues

“Wait,” I hear you say. “What’s that got to do with fatigue?”

Well, staffing issues in airports lead to delays, which lead to longer hours for crew, which can lead to tiredness and fatigue.

- The Russia Ukraine conflict

Longer routings mean more time in the air which can lead to, you guessed it, more tiredness and fatigue.

- Strikes

Strikes = delays and disruption = … same old story.

Now, just identifying random things which might be increasing fatigue levels isn’t really going to fix it. Having some real, human conversations about it might.

- If you’re a pilot, don’t just think about now, think about 10 hours later.

- Get some decent controlled rest policies into your operation.

- Consider ways to improve sleep management, especially if you’re doing hideous time zone crossing flights.

- Stop using tees like “sleep science” and harping on about circadian rhythm. Start talking about how to recognise fatigue, what that means for your performance, and what to do about it.

The Full Monty

So, that is the (Canadian) Safety Watchlist 2022 and if you want to, you can read the full thing here, (including the bits on fishing).