Highlights (updated 2024)

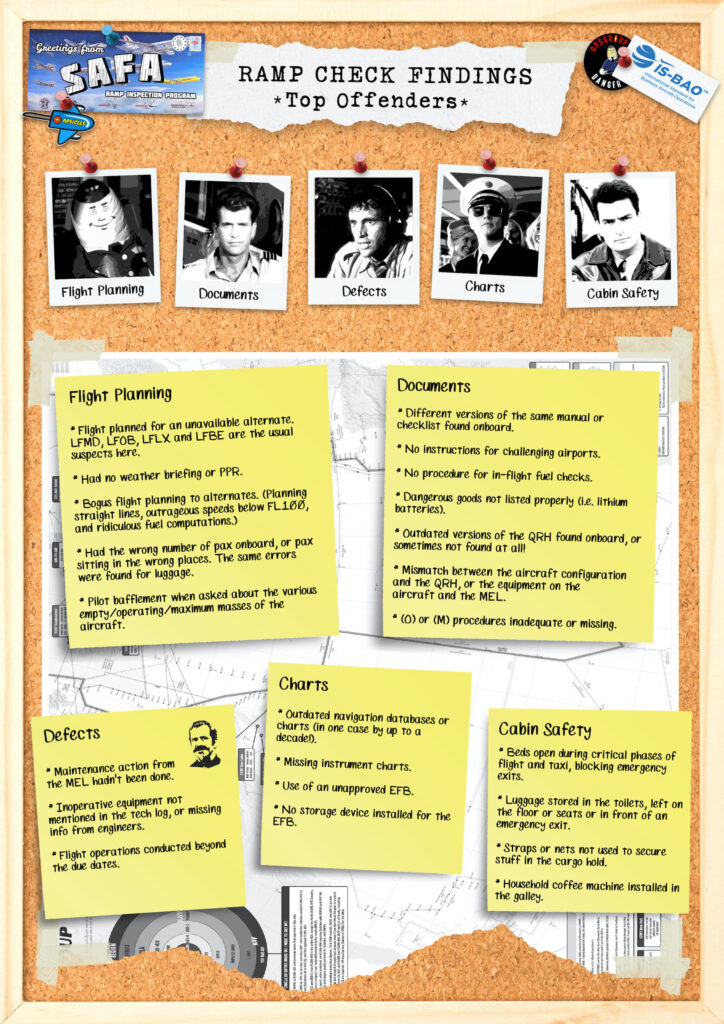

- The Top 5 SAFA Ramp Check Findings are Flight Planning, Aircraft Documents, Defects, Charts, and Cabin Safety

- It’s not a knowledge test, so feel free to say “I don’t know”

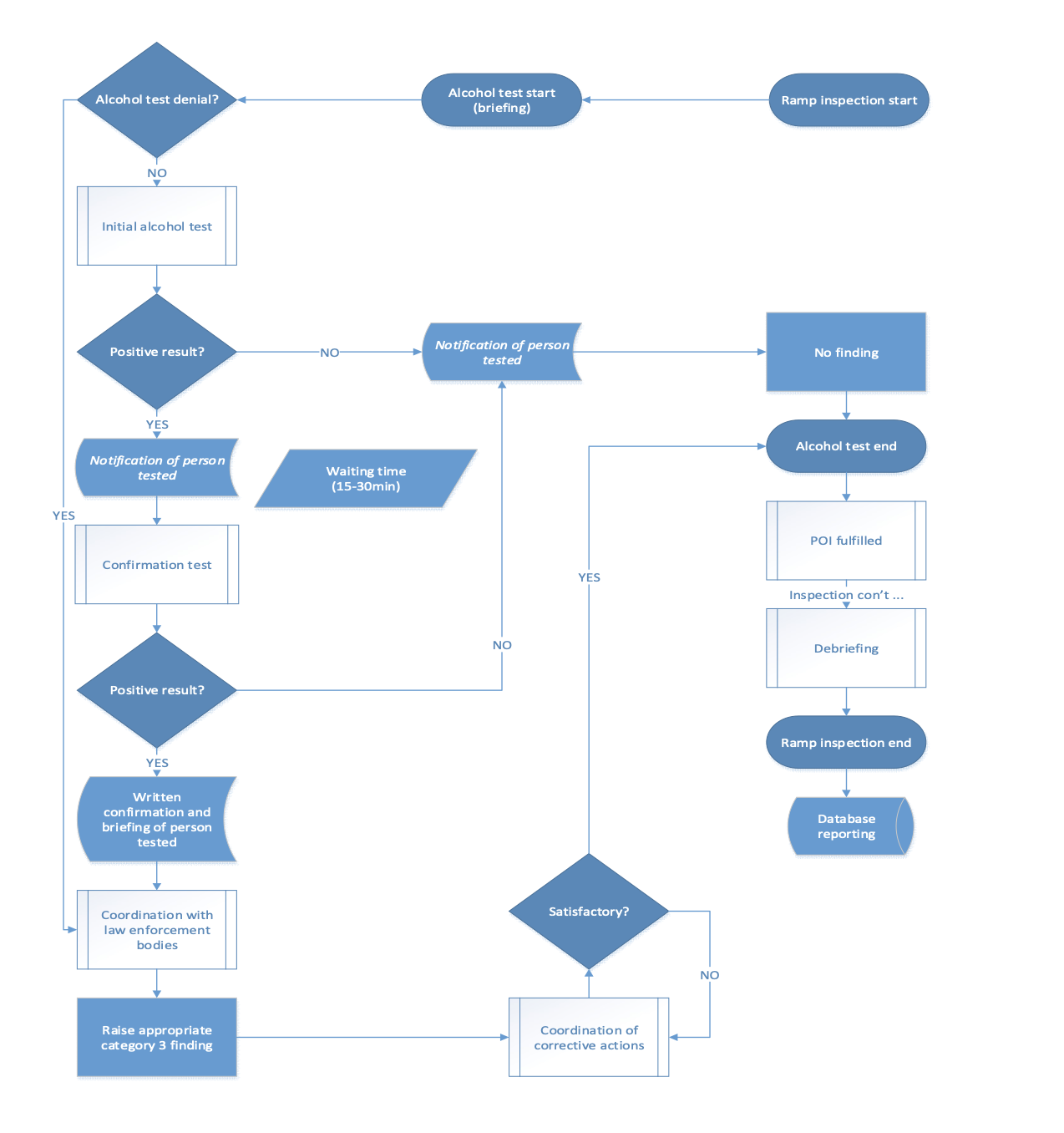

- Alcohol testing is now common, see below for a guide

Ramp check! Not our favourite couple of words in the aviation vernacular, but when your number’s up, wouldn’t it be good to know what things most of us are getting wrong?

Well, here they all are, in a handy little guide. Download, print, attach to wall-of-your-choice, and enjoy.

What do we base this on? Well, something pretty special happened recently. The French DSAC partnered up with IS-BAO to take a look at hundreds of de-identified ramp check findings in order to analyse the most frequent CAT 2 and CAT 3 findings in business aviation.

This is “special” for three reasons

- It’s great that an aviation regulator has actually shared this info because now we can see the top things we’re getting wrong.

- If we can see the top things we’re getting wrong, we can stop getting them wrong, and then ramp checks become faster and more efficient for everyone.

- It’s great that this specific aviation regulator happens to be the one from France – because that’s where a lot of ramp checks seem to occur!

So, all good. IS-BAO published the results here, and it’s worth giving that a read first before we press on…

The Top 5 Offenders

As the good folks from IS-BAO point out – EASA Ramp checks cover 52 inspection items spread over 5 areas: flight deck, cabin, aircraft condition, cargo, and general/other.

But some of those 52 items generate more findings than others. The DSAC/IS-BAO study found that the top inspection items by number of CAT2 and CAT3 findings for business aviation were these ones:

1. Flight preparation (RI checklist item A13)

2. Mass and balance calculations (A14)

3. Manuals (A04)

4. MEL (A07)

5. Checklists (A05)

6. Defect notification and rectification (A23)

7. Navigation/instrument charts (A06)

So essentially, these findings all relate to five key areas: Flight Planning, Documents, Defects, Charts, Cabin Safety. Get these right, and your “sweatin over a ramp checkin” days are over, partner!

Have you been ramp checked recently?

Let us know! Where did it happen? How did it go? What things surprised you?

As always, we will de-identify anything you share with us before we tell anyone else about it. But we’d love to hear your stories, and other people will too! Our idea is to gather together as many of these stories as possible, and put them into a little book to help give other pilots and operators an idea of what to expect. So if you’ve got a story to share, send us an email at news@ops.group

In related news: the EASA RIM has been updated.

What’s the EASA RIM? Europe’s version of the Pacific Rim movie only with ramp inspectors saving the aviation industry from danger? Or just an updated version of a rather boring manual?

EASA Ramp Inspectors, heading out to work.

Sadly, just an updated manual.

EASA have made some amendments, corrections and added some other details to their Ramp Inspection Manual, so here is our guide to their 131 pages of guidance (and an Appendix).

What’s up?

The Changes to the RIM are contained in a 131 page document here. So this is the doc that crew might want to read. (The massive doc that ramp inspectors use is called the Appendix – we’ll get to that later).

The big stuff to look out for (that we could see) is stuff on Alcohol testing and they’ve changed the name of the “Standard Report” to “Safety Report”.

Page 76.

Let’s start with something small.

This isn’t actually a change, but just something we think might be of particular use. It is the Checklist for on-the-job training for ramp inspectors. Basically, it is a long list of all the stuff they need to check. Which means it’s a long list you might want to check so you know what you are going to get checked on.

Alcohol Testing.

Scroll to page 98 (section 10.3) and it lays out all the info on alcohol testing and how it should be carried out. There is a lot of info here (most of it for the inspecting agents rather than you) but still not uninteresting to read.

The general principles are that it should be done somewhere private, out of sight of anyone else, and if you aren’t happy with the spot they pick then chose another.

They’re testing to see if you blow more than 0.2 grams of blood alcohol concentration. If you blow below that then you pass. If you test above then don’t panic straight out, they must do a follow up confirmation test which mustn’t happen before 15 minutes, or outside of 30.

Certain drinks can mess up the results:

- “Aromatic beverages” like fruit juice (never heard them called that)

- Mouth sprays with alcohol content

- Medical juices (I don’t even want to know what that might be)

- Burping on the test can create false positives.

Here is a particularly hideous flow chart of the entire process.

We think it’s easier to sum up stuff like this:

- Don’t ever go to work drunk. Most operators/states specify a minimum time between drinking and working but if you aren’t sure 12 hours is a generally decent one to work off.

- Of course even 12 hours won’t get you sober in time if you’ve been on a mega bender the night before. So don’t do that.

- If you wake up before you’re report time and realise you’re drunk/potentially drunk then CALL SICK!

- If you think a colleague is drunk, stop them from going to the airport! Report them if you need to.

- If you are at work, and get picked for a random test, make sure they do it correctly, in a private space following the right procedures.

- If you blow positive then don’t panic (unless you are drunk in which case do panic, you’ve messed up bad, partner). Have a think if you’ve maybe ingested something that could cause a false positive. Tell the inspector and wait for the confirmation test. They leave it at least 15 minutes, but don’t push for more than 30.

Moving onto The Appendix.

The Appendix to the RIM is a whole 304 pages filed with information on ramp check instructions and pre-described findings.

Many of which have just been updated.

Now, you might be thinking “why do I care how they’re instructing their inspectors on stuff?”. But you should care because if you know how they’re inspecting stuff, then it makes it a whole lot easier to not mess up on ramp checks and getting told off.

If you just want to scroll through the list of changes, then take a look here at the first 7 or so pages.

If you want a full description in standard EASA English, then read the whole 304.

If you want a summary of the changes then check this out.

Other useful stuff.

We wrote a whole post on ramp checks a while back and the stuff we wrote in that hasn’t really changed that much.

While ensuring you are complaint is important, remember is works both ways. Ramp Inspectors need to follow the rules and procedures as well. Particularly when it comes to not delaying you or disrupting your duties too much.

The manual only recommends they must give you 8-10 minutes of quality quiet time to set up for a flight. If you need more for safety reasons then tell them the time you need them to complete their checks by.

Final note.

Ramp checks can be frustrating. The best way to reduce that is make sure everything is in order and be prepared for them.

There are some airports we’ve heard are particularly vigorous with them:

- Anywhere in France

- Florence, Italy

- Edinburgh, Scotland

- London Heathrow

- Copenhagen, Denmark (keen on the breath tests)

- Amsterdam, Netherlands (also keen on the breath tests)

Let us know where you’ve experienced them so we can update the list!

More on the topic:

- More: EASA’s New Cyber and Data Risk Rule for Operators in Europe

- More: Ops to Europe: How to Get a Third Country Operator (TCO) Approval

- More: EASA Removes CZIBs: Middle East Risk Gets Harder to Read

- More: Why EASA has Withdrawn Airspace Warnings for Iran and Israel

- More: Russia: Aircraft Shot Down, New EASA Airspace Warning

More reading:

- Latest: FAA Warns on Runway Length Data and Overrun Risk

- Latest: EASA’s New Cyber and Data Risk Rule for Operators in Europe

- Latest: Airport Spy: Real World Reports from Crews

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly

Under the What’s Up heading, the link in the first paragraph:

The Changes to the RIM are contained in a 131 page document here. So this is the doc that crew might want to read. (The massive doc that ramp inspectors use is called the Appendix – we’ll get to that later)

The 131 page link thingy isn’t linking…

I also tried looking it up has it been removed from EASA?

Hi Chris, yep it looks like that 131 page doc just covering the changes has been removed from the EASA site. But here’s the link to the EASA page that has the RIM doc, plus the Appendix used by inspectors: https://safa.easa.europa.eu/site/safalib

Yep… 0.2 or national limit if lower:

RIM Edno 3.0 Page 110:

In accordance with ARO.RAMP.106, alcohol testing on flight crew and cabin crew members are carried out in [name of the Member

State] by ramp inspectors. For these crew members, while on flight duty, the breathalyser test results should not exceed the level

equivalent to [0.2 grams/national statutory limit if lower] of Blood Alcohol Concentration per litre of blood, as published here:

[link to the national AIP, national laws, EU regulation].

“They’re testing to see if you blow more than 0.2 grams of blood alcohol concentration”.

I think its the lower of 0.2 or the national limit… Some EU nations have a limit closer to 0 than 0.2, so beware!

Interesting that SAFA checks have now moved away from the Flt Planning for the full published arrival route – FRA was a nightmare where finders were issued if the full procedure was not planned on the OFP. We changed this in 2016 when ICAO adopted the principle: fuel for takeoff and climb from the aerodrome elevation to the initial cruise ;eve;/altitude, taking into account the expected departure routing, fuel from the top of climb to the top of descent including any step climb/descents, fuel from the top of descent to the point where approach procedure is initiated taking into account the expected arrival routing and fuel for the approach and landing at the destination. the words expected qualify the departure and arrival routes and allow operators to plan the distances that are reasonably expected. This cuts off some 60 – 80 track miles for a FRA arrival landing to the west. This is “probabalistic” flight planning and is the state pop the art in flt planning today. So now SAFA has switched to track to alternate and while GC is a little problematic over 50 years of flying I find that most alternates can be flown GC plus 25 on departure and 25 on arrival, but precision is the better solution.

the other comment is the ref to “It’s great that an aviation regulator has actually shared this info because now we can see the top things we’re getting wrong.” question here is “are the ‘regulators’ getting it right – have had many inspections over the years and challenging the findings have proven the ‘regulators’ are not always right.