Questions about the North Atlantic pop up a lot, and every time we think we’ve got all the answers, someone else manages to come up with a question we can’t (immediately) answer.

We wrote NAT Conundrums: Volume I last year, which you can read here. That post covered the following three conundrums:

- To SLOP, or not to SLOP?

- What’s the difference between the NAT Region and the NAT HLA?

- Can I fly across the North Atlantic without Datalink?

So today we thought we’d take a look at three more questions we’ve seen recently including an interesting ‘what to do if…?’ scenario.

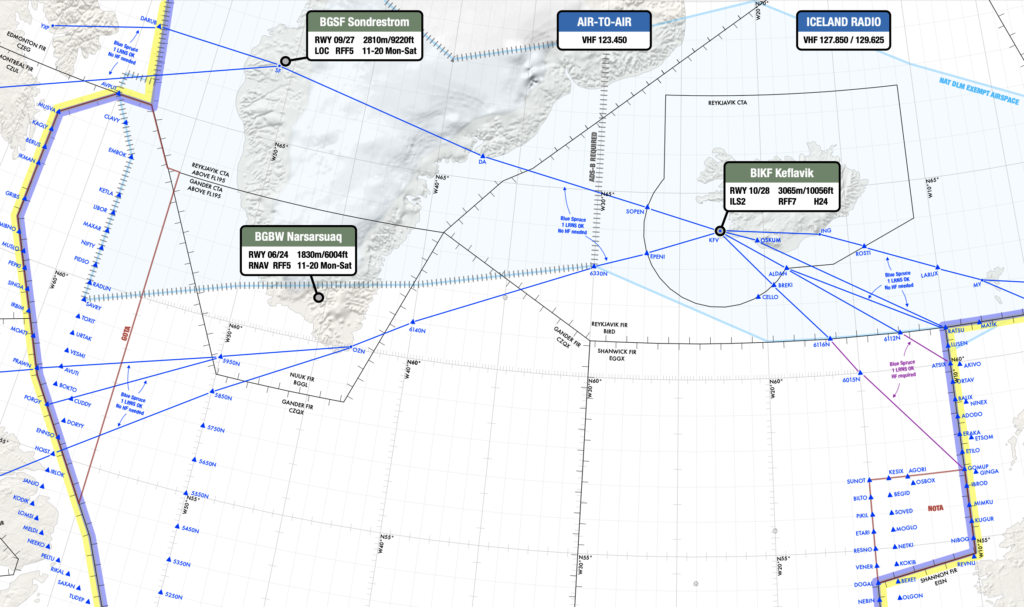

4. Do you need to plot on Blue Spruce Routes?

Plotting is less drawing your position on a big paper map and more confirming there are no errors with your navigation, which means you can do this on paper, or via some sort of electronic system.

The reason we want to check for errors is because the North Atlantic is a big place, without radar, (although ADS-B is helping with this a lot now), and we are very reliant on our GPS navigation systems. Some routes use just lat/long points meaning there is an added chance of input error by the pilot. So we check where we are and make sure it is where we should be.

But the Blue Spruce Routes are defined routes so there’s no risk? Well, no, there still is, because you’re still flying over big chunks of ocean without much backup. So checking for errors is still a very good idea.

5. Do we still fly Weather Contingency Procedures on Blue Spruce routes?

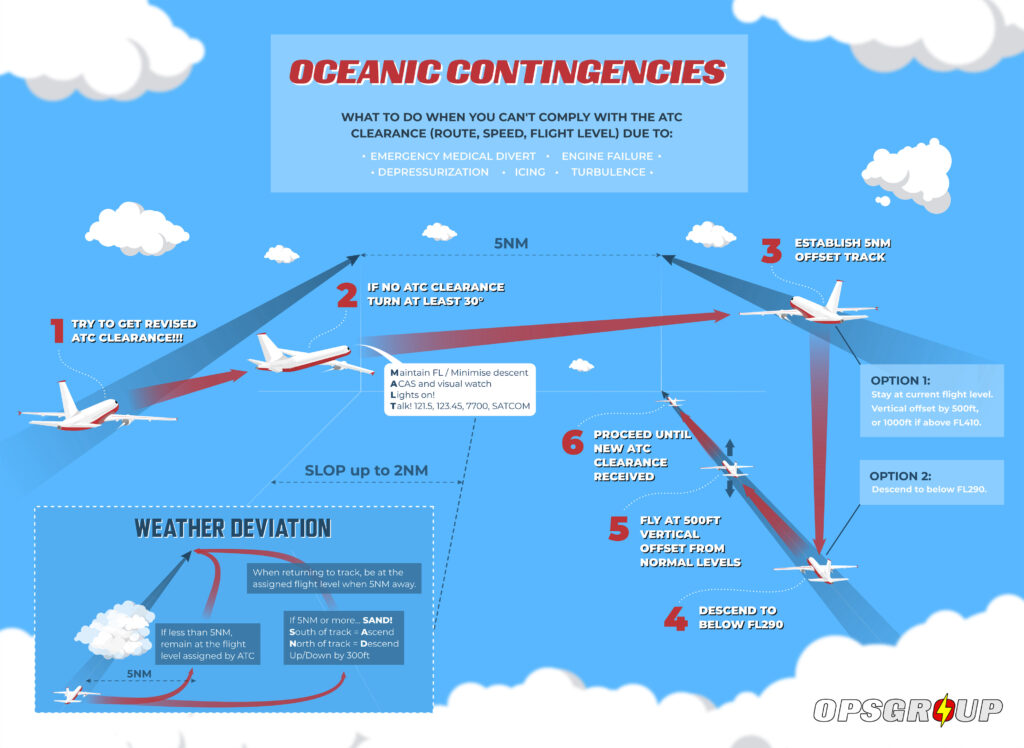

The Weather Contingency Procedures are more oceanic contingency procedures than NAT HLA specific one.

In fact, since Nov 2020, there has been one standard set of Contingency and Weather Deviation Procedures for all oceanic airspace worldwide – and there are no special exemptions for the Blue Spruce routes.

So they are a good thing to do if you encounter a weather situation and cannot get a re-clearance from ATC.

Which leads us to the big question…

6. When can we disregard an ATC clearance and follow the contingency procedure instead?

Let’s set the scene.

You’re flying in the NAT and there is a big old storm up ahead which you need to deviate around. Obviously, whatever happens, you can’t fly into it.

So what do you do?

Well, NAT Doc 007 provides you with some guidance: Apply the weather avoidance contingency procedures.

They are fairly straightforward. If the deviation you need will be less than 5nm then stay at your level, if its more than 5nm, then you’ll need to climb or descend 300’ depending on which way you’re avoiding. You can use ‘SAND’ for that – turning south? Ascend. Turning north? Descend.

Which way to turn depends on whether there are busy tracks to the left or right of you, and how much you’ll need to deviate by based on storm position (and wind). Use your TCAS and some airmanship on this.

Right, scene set. So, do you just launch straight into the contingencies?

No. It comes down to whether or not you can get a clearance from ATC.

No. It comes down to whether or not you can get a clearance from ATC.

You can keep this fairly simple as well:

- You can’t get a clearance because there just ain’t time. In this case, it is probably best to declare a PAN and go straight into the avoidance contingency procedure. Don’t delay waiting for ATC clearance if its not safe. Aviate and avoid the weather, talk to ATC as you do it.

- What if you can’t get a clearance because you just can’t get hold of ATC? Another easy one – follow the contingency procedure, but keep transmitting what you’re doing so other traffic know.

- What if ATC can’t give you a clearance? This might happen if it is particularly busy out, perhaps other aircraft are already avoiding, and so they can’t guarantee separation. In this case, they should inform you of the issue and ask you what your intentions are. Which will probably be following that contingency procedure, because you obviously aren’t going to fly into the storm.

Which brings up to situation number 4. The less simple one.

- What to do if ATC give you a clearance that isn’t acceptable to you? First up, if you have time to request a re-clearance then do this, advising why their first one doesn’t work for you. If you don’t have time, then a PAN call with your intentions (contingency procedure) is going to be the way to go.

But remember – you need a good reason to disregard an ATC clearance like an immediate threat to safety. You can’t just do it because they told you to go right and it means a bigger detour than left, or because you just don’t fancy a temporary level change.

This is where the conundrum comes in – because folk have different views on what is an acceptable reason for disregarding a clearance.

- Obvious and immediate threat to safety? Do whatever you need to do to stay safe

- Might have a future fuel concern because of a larger deviation, or a level change? Well, it’s not immediate and the traffic conflict you get yourself into by disregarding may be the bigger priority here…

Contingencies – for when going through isn’t an option.

We asked around.

The general consensus was that fuel is unlikely to constitute enough of an ‘immediate threat’ to be an acceptable reason. Things like ETOPS fuel are for dispatch planning so is not particularly relevant in flight. However, if you’ve already burned through your contingency, and are already running some calculations because the fuel is looking tight, then a ‘Pan’ call and doing what you need to do might be acceptable.

What does Doc 007 actually say?

It says the pilot should either follow the clearance or state their intentions.

There is a level of ambiguity here because there is always that need for the Commander to be able to decide another course of action is safer. A good way of thinking about it is that a crew never have to follow the letter of the law – it isn’t there just to be the law, it is there to try and keep us safe – so doing what is most safe, with the same intent for safety in mind, is always acceptable.

What do other rules and regulations say?

The US FARs have this as fairly general rules:

’91.123 Compliance with ATC clearances and instructions.

(a) When an ATC clearance has been obtained, no pilot in command may deviate from that clearance unless an amended clearance is obtained, an emergency exists, or the deviation is in response to a traffic alert and collision avoidance system resolution advisory;

(Something about changing from IFR to VFR, and then -)

(b) Except in an emergency, no person may operate an aircraft contrary to an ATC instruction in an area in which air traffic control is exercised.’

What did a helpful person in the North Atlantic ICAO office say?

Well, much the same. The contingencies are there to account for situations where ATC is unable to provide a clearance, or where the clearance they can provide doesn’t solve the flight’s problem. In these cases, the pilots should advise ATC their intentions and do what they need to do to stay safe.

Again, no clear line drawn as to where ‘staying safe’ might necessarily fall, particularly when it is a concern over fuel.

They did say they would never issue a weather deviation clearance requiring a climb without a ‘negotiation’ first.

So, the answer is…

Well, we don’t have it. At least not a clear cut, black and white one.

The general view seems to be that it needs to be a judgement call. If you have a genuine safety reason that makes you question whether you should be following an ATC clearance, then declare a PAN, state your intentions, and do what you must.

Just be comfortable that your decision does still maintain that same intent for safety. Definitely going to result in a low fuel situation? Or just don’t fancy being stuck at a lower level? There is a line, but where you set it might come down to that flight, on that day, in those specific circumstances.

More on the topic:

- More: New NAT Doc 007: North Atlantic Changes from March 2026

- More: What’s Changing on the North Atlantic?

- More: Timeline of North Atlantic Changes

- More: Spoofed Before the NAT? Here’s What to Do

- More: Shanwick Delays OCR Until Post-Summer 2026

More reading:

- Latest: FAA Warns on Runway Length Data and Overrun Risk

- Latest: EASA’s New Cyber and Data Risk Rule for Operators in Europe

- Latest: Airport Spy: Real World Reports from Crews

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly

Well written, Rebecca, as usual. A point I like to make is, I understand contingency rules, We need to have them…BUT my goal, is always stay ahead of weather deviations/communication so that I never, ever have to use them. It just seems like sometimes folks miss that point. Also, back to Command Authority, in your A-380 a little different…but in a lowly TWO engine aircraft, G-650 for example, one engine quits, I may just be headed for the nearest rock…because I am worried why the first engine quit, and wondering when the next/only one left is going to quit…sure, I’ll be talking to everyone I can, lights on, etc….just not offsetting and pressing on.

Worldwide, have you found any IPA’s that can compete with some of them in the USA ? (Although you might not be a “hop head” .

Cheers.