Here’s a startling statistic – according to the Flight Safety Foundation, straight-in approaches are twenty-five times safer than circling ones. Twenty-five times!

It’s no wonder then that the NTSB are concerned. In fact, they identified that there were ten major accidents involving Part 91 and 135 operators between 2008 and 2023 while flying a circling approach.

We smell risk, and so does the NTSB. Which is why in March 2023 they issued a new safety alert. Asides from the obvious risks of operating a high-performance aircraft at low speed and altitude in poor visibility, there appears to be another threat too – key differences between ICAO PANS-OPS and US TERPS.

Let’s take a closer look…

The NTSB Alert

The NTSB’s key takeaway seems to be this: you don’t need to circle. You can also request a runway aligned approach, or if that isn’t practical, a diversion.

Of course, if a straight-in approach isn’t available, a diversion for a commercial operator would likely be a tough sell when there is a legal and procedural approach to the runway in front you.

But if you do, it implores you to understand and thoroughly brief the risks.

The reality is that circling approaches are far riskier. They involve manoeuvring an aircraft low to ground, and low in energy in marginal conditions. This opens the door to two major dangers – loss of control, and collision with the hard stuff.

They’re also not particularly conducive to a stabilised approach, which typically involves being runway aligned by 500’ off the deck in VMC conditions, or higher in the soup.

Then there is the elephant in the room – our own limitations. As pilots we are responsible for setting our own personal limits. More often than not, these rest within the ones defined by law. Familiarity, experience and conditions all come into play when assessing our appetite for risk.

In other words, just because a procedure is legal doesn’t mean we should fly it.

The NTSB also identifies that training (or lack of) is an issue. When was the last time you circled in the simulator? To fly circling approaches safely, we need to be practicing them in our re-currents regularly and in different conditions.

This is where the NTSB alert ends, but there may also be more to it than that – the way circling procedures are designed may also be partially to blame…

The PANS-OPS versus TERPS Conundrum

It will likely be no surprise that instrument approach and departure procedures are designed to keep aircraft safely away from terrain and obstacles to internationally accepted standards.

To make this happen, there are two main sets of procedures:

- ICAO Procedures for Air Navigation Services (PANS-OPS) used throughout Europe and in many other parts of the world. You can these in ICAO Doc 8168.

- United States Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS) used throughout the US, Canada and in some other countries such as Korea and Taiwan. Those details are in FAA Order 8260.3D1.

When we circle, we need to understand how the procedure was designed (PANS-OPS or TERPS) and what the differences are, which can be significant.

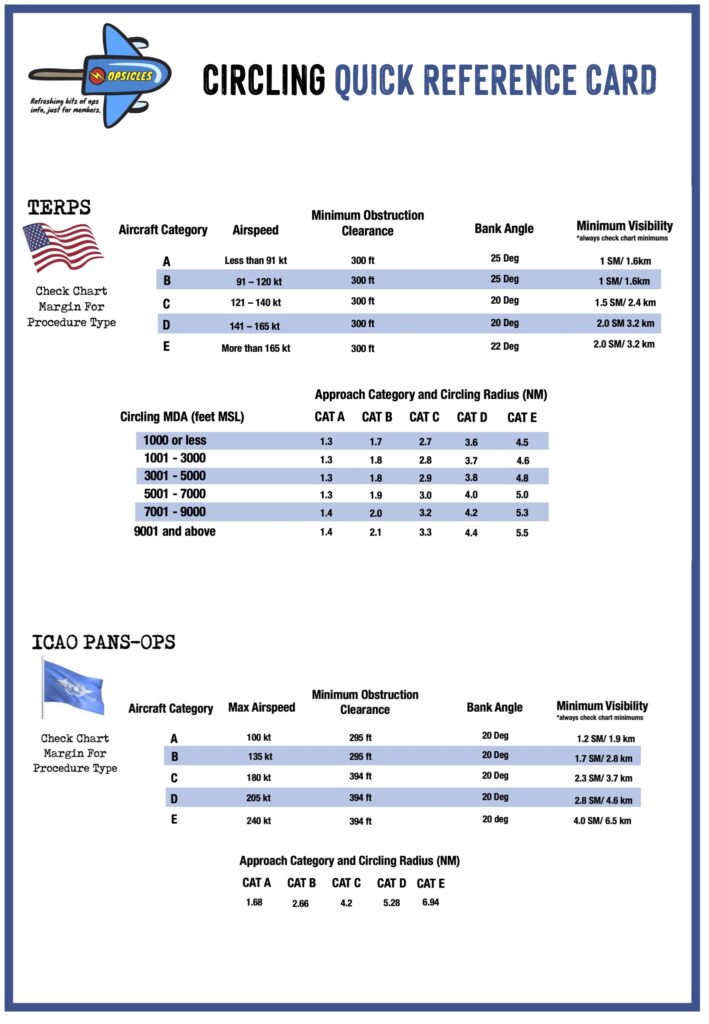

The reality is that under TERPS, in some cases aircraft are required to fly slower, with higher angles of bank in more restrictive circling areas despite improvements made back in 2013. And all of this can happen in lower visibility than in PANS-OPS procedures.

Could this be one of the contributing factors to circling accidents in the US and Canada? Possibly.

What are the differences?

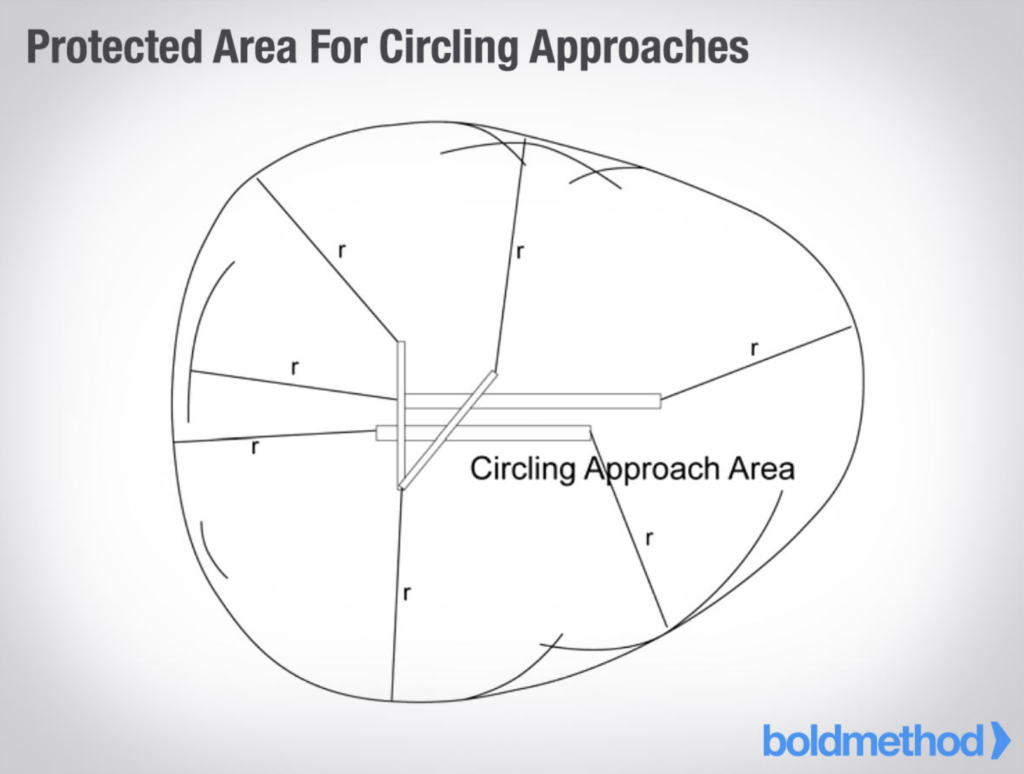

In both systems, a radius is drawn from the centre of the threshold for a particular runway inside of which obstacle clearance has been assessed. It’s known as a circling area, or domain.

Protected areas are drawn from arcs from the center of each threshold. Courtesy: Boldmethod

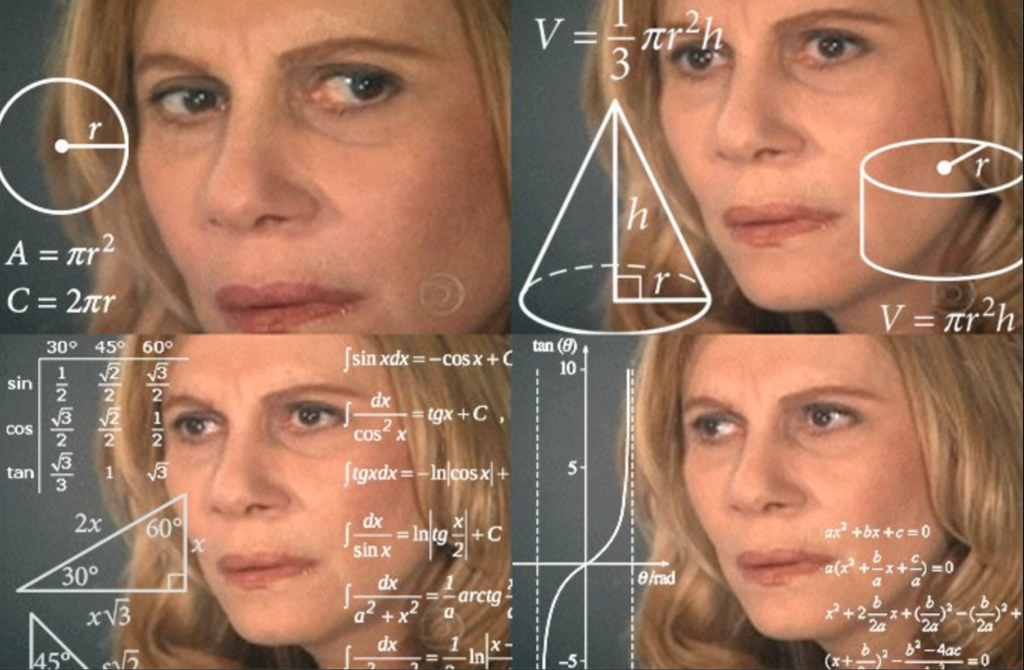

The size of this area increases with aircraft category – essentially if you’re heavier, you need to fly faster which means your turn radius increases, and you need more room to circle. This is taken into account using TAS and bank angle when the procedure is designed – along with a healthy dose of mathematical wizardry.

But herein lies an essential difference.

PANS-OPS bases TAS on altitude and circling IAS. TERPS on the other hand bases this on altitude and IAS at threshold. The result is a much smaller circling area, and in some cases higher bank angles.

The maths behind circling approaches is complicated, but the key difference between PANS-OPS and TERPS is IAS.

Take a Category C aircraft for instance (threshold speed 121 – 141 kts). Under PANS-OPS the circling area for an approach would extend to 4.2nm, while under TERPS (with an MDA of less than 1000’) the same area would extend only as far as 2.7 nm. For lower category aircraft, this also increases minimum bank angle beyond 20 degrees. Things can start to get tight.

In a nutshell, because ICAO uses higher IAS for its TAS calculations, and assumes a lesser angle of bank, its circling areas are far roomier.

International operators in particular may be at risk of straying outside of the circling area if they are not familiar with the more restrictive TERPS procedures. To make matters worse, some countries may not be 100% one way or the other. A straight-in approach may be designed to PANS OPS, while the circling approach is designed to keep you within a TERPS assessed area – Mexico and Chile being examples.

And in some cases, all of this can happen down to a minimum visibility of just 1.5 miles (2.4km) under TERPS, versus 2.3 miles (3.7km) under PANS-OPS.

How do I know what kind of procedure I’m flying?

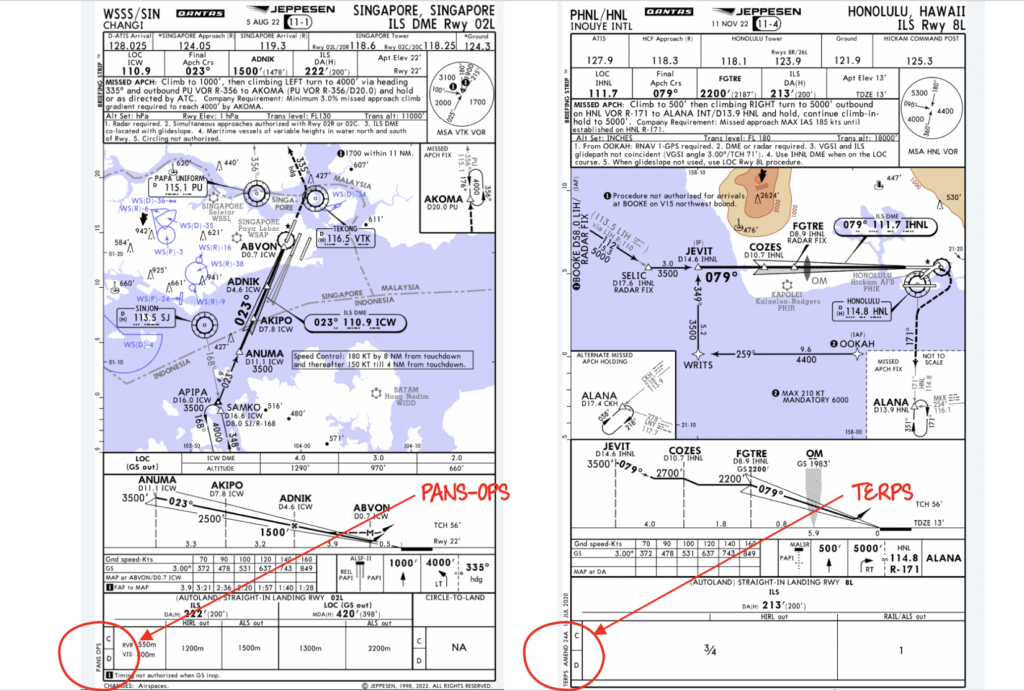

Get your magnifying glass out. It will be written in the margin of your chart. If you’re using Jeppesen, have a look at the bottom left-hand side, written vertically. It’s far from obvious.

Once you’ve established what type of approach you’ll be flying, you’ll need to think about speed, your circling area, and whether the visibility is appropriate. We’ve put together a little cheat sheet that may help…

The Stats Don’t Lie

We’re getting circling approaches tragically wrong. What the industry is currently teaching pilots doesn’t seem to be cutting the mustard – and the Flight Safety Foundation agrees. Pilots need to be more aware of the design criteria used for circling approaches, and the limitations that places on their aircraft. This also needs to be made far clearer on approach charts if we’re to reduce risk on these challenging manoeuvres.

More reading:

- Latest: FAA Warns on Runway Length Data and Overrun Risk

- Latest: EASA’s New Cyber and Data Risk Rule for Operators in Europe

- Latest: Airport Spy: Real World Reports from Crews

- Safe Airspace: Risk Database

- Weekly Ops Bulletin: Subscribe

- Membership plans: Why join OPSGROUP?

Get the famous weekly

Get the famous weekly

As DO for a 135/121 operator in the 1990’s we simply prohibited circling approaches in our Convairs. Avoiding the hazard is the ultimate risk control…

Our company uses a minimum of 1000’ ceiling and 3 nm viz for circling

Thanks for sharing Ian – perhaps more conservative company SOPs are an important piece of the puzzle!

I think that the pilots must practice more times circling approaches every recurrent flihts every 6 month.

Almost 6 to 10 years of schedule flights I did a circle approach only 1 time

In my experience CAE have at least tried to address the Terps Pan Ops issue in briefing’s and I feel a lot more informed, but as a pilot I am fully conscious of the circling risk. I think the cavalier consider it ‘just like a visual circuit, basic skills you should have, get on with it’. Have done them many many times VMC around Europe, and that maybe a fair assessment but never never down to minimums and that is the danger, no doubt. Everything has to be perfect to get stable.

Several things come to mind based on my experience as an instructor and TCE for one of the primary training providers, and a current 91/135 Captain on a Falcon.

1. There are only a few authorized circling approaches available to us in the sim for training and checking. We can position crews at other, more challenging airports, but we’re unable to give “credit” since they are not “approved”

2. My observation from the back seat as an instructor…crews continue to be distracted with the inside of the cockpit once they have acquired the runway environment. This leads to crew members being behind during visual maneuvers and attempt to continue the approach and landing in an unstable condition.

3. Just something we don’t do that often. 4. And, the places where ATC wants you to perform a circle should be refused.

IE: ILS 6 circle RWY 1 KTEB.

That’s been a disaster waiting to happen for years.

Airspace, obstacles, wind, densely populated area, and I always got this approach at night.

I believe FAA has a separate endorsement for circling on the type rating and it is tested every recurrent. This may justify the reduced mins. I don’t think regulating circling mins to almost VFR is the answer. If pilots are trained and current and read articles like this I think TERPS should be acceptable. Personal mins is an excellent point.

Good article. As in most things the devil is in the details. Circling has become more hazardous as wing designs and airspeeds increase. You can’t really determine 2.7 miles from DER as you circle so yes planning is everything. I have 10 type ratings with no circling restrictions as is common today. (1000/3) Practically speaking I would accept a tailwind with adequate runway rather than circle to land. For airlines these is generally not an issue. A 737, with the paperwork, can take up to 20 knots. For corporate operators and small airports circling is a very large risk. Simulators generally don’t have good fidelity with circling maneuvers.

Collins’ FMS can paint a radius around a point on the MFD. Flight Safety teaches this. I have found it helpful, as well as painting an extended centerline on the MFD.

Thanks Torrey – I agree. Great technique for situational awareness!

Absolutely 💯 % spot on.

It may be alright in your average GA(Part 91) aircraft but in larger more powerful types both jets & turboprop it gets a lot more tricky to do safely.

Obviously having a tailwind on final is never a good thing but maybe a whole heap better than circling around to get the headwind particularly if terrain & poor vi’s are involved.