A whole bunch of procedural stuff will be changing from 5 Nov 2020, with the release of a new amendment to ICAO’s Procedures for Air Navigation Services document. There will be changes to Oceanic Contingency and Weather Deviation Procedures, Wake Turbulence Separation, SLOP Procedures, and how the FAA defines Gross Navigation Errors.

What is the PANS-ATM (ICAO Doc 4444)?

Procedures for Navigation Services – Air Traffic Management. In other words, the ‘go to’ manual for aircrews who operate internationally. It explains in detail the standard procedures you can expect to be applied by air traffic services around the world, and what they expect in return.

Here is a summary of the most important changes coming on 5 Nov 2020. Thanks to Guy Gribble at International Flight Resources for this update.

Oceanic Contingency Procedures

Basically, what you should do if you need deviate from your flight path without a clearance. Weather avoidance, turbulence, depressurisation, engine failure – you get the picture. Published procedures are changing: there will be one standard set of Contingency and Weather Deviation Procedures for all oceanic airspace worldwide.

If you’ve been flying in the North Atlantic Region over the past year and a half, you’ll be familiar with how it works – the new procedures were introduced there back in March 2019, and now they’re being rolled out everywhere.

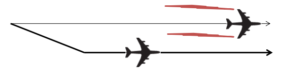

The main change here is that Contingency offsets which previously were 15 NM are basically now all 5 NM offsets with a turn of at least 30 degrees (not 45 degrees).

For more on this, check out our article.

Wake Turbulence

Flight Plan Category

There will be a new wake turbulence category for flight plans:

No longer will ‘Heavy’ rule the skies. ‘Super’ is about to be added, which will cover the largest aircraft including the A380-800, and Antonov 225. You will even get to say it after your callsign on initial contact with ATC.

ICAO Doc 8643 will shortly include all aircraft which qualify for the category.

You’ll need to tell them your category in Flight Plan Item #9 too. For Super, the letter ‘J’ is what you’ll need to include.

Here’s the new line up:

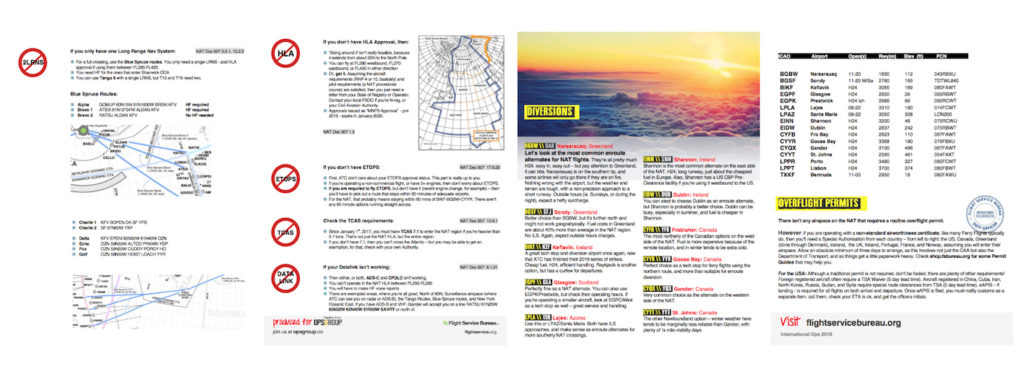

J – SUPER (Check Doc 8643 to see if you qualify)

H – HEAVY (Max take-off weight greater than 136,000kg/300,000Lbs)

M – MEDIUM (Max take-off weight greater than 7,000kg/15,500Lbs)

L – LIGHT (Max take-off weight less than or equal to 7,000kg/15,500Lbs)

Wake Turbulence Separation Categories

Countries may choose to use the ICAO wake turbulence codes above to determine how much room to give you from preceding traffic, or they can elect to use a grouping.

Currently, ICAO groupings are based simply on weight and there’s only three of them. The problem with that approach is that sometimes the separation provided is excessive which slows down the flow of traffic and creates unnecessary delays.

The US and Europe were on to it when several years ago the FAA and Eurocontrol joined forces to look at the wake characteristics of aircraft in more detail. They came up with a better system – it was a process known as Aircraft Wake Turbulence Re-Categorization or simply, RECAT.

Turns out that when you take into account factors such as approach speeds, wing characteristics and handling abilities of various aircraft it is possible to safely reduce separation.

As a result, six new categories were created. You can read about those in FAA SAFO #12007 and EU-RECAT 1.5 if you would like to know more.

The point is, ICAO is now adopting those categories.

So why does it matter?

Because the separation applied when following smaller aircraft may be reduced to as low as 2.5nm on approach. Closer than you may be accustomed to.

Out with the old, in with the new. Here’s what you can expect to see in November:

Old:

HEAVY (H) – aircraft of 136,000kg or more

MEDIUM (M) – aircraft less than 136,000kg but more than 7,000kg

LIGHT (L) – aircraft of 7,000kg or less

New:

GROUP A – ≥136,000kg and a wingspan ≤80m but >74.68m

GROUP B – ≥136,000kg and a wingspan ≤74.68m but >53.34m

GROUP C – ≥136,000kg and a wingspan ≤53.34 m but >38.1m

GROUP D – <136,000kg but >18,600kg and a wingspan >32m

GROUP E – <136,000kg but >18,600kg and a wingspan ≤32m but >27.43m

GROUP F – <136,000kg but >18,600kg and a wingspan ≤27.43m

GROUP G – <18,600 kg or less (no wingspan criterion)

Separation standards will soon be published accordingly.

Strategic Lateral Offset Procedures (SLOP)

Wait, what?

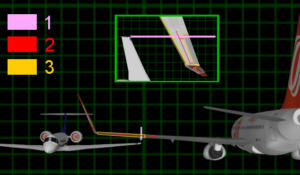

As a result of extremely high levels of accuracy in modern navigation systems, if an error in height occurs there is a much higher chance of collision. It is also greatly increases the chance of an encounter with wake turbulence.

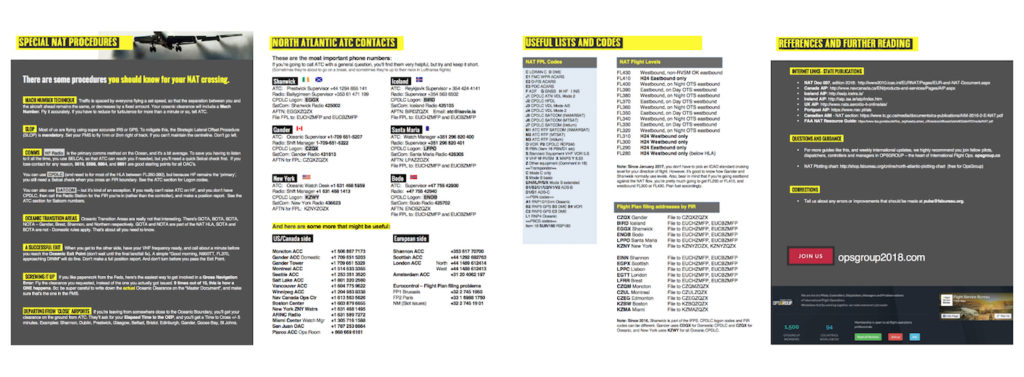

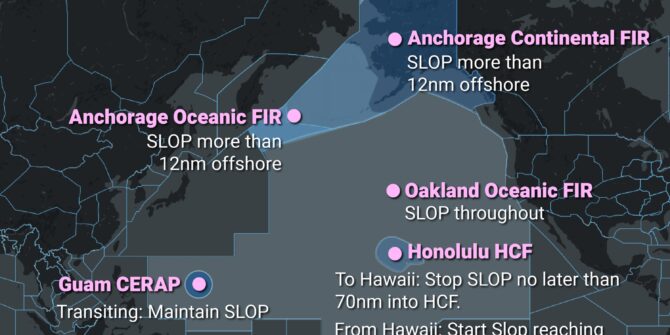

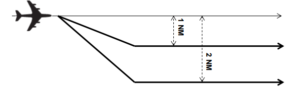

In some airspace, when the lateral separation applied or the distance between adjacent parallel routes is greater than 6nm, aircraft can deviate up to 2nm right of track without a clearance. This is what is known as SLOP.

The way in which it is applied is changing

Where the lateral separation minima or spacing between route centerlines is 15NM or more; offsets to the right of the centerline will allowed up to 2nm.

When the lateral separation minima or space between route centrelines is less than 15nm (but more than 6nm), you will be able offset up to 0.5nm right of track.

So, it is important you are familiar with what kind of lateral separation is being applied in the airspace you are operating.

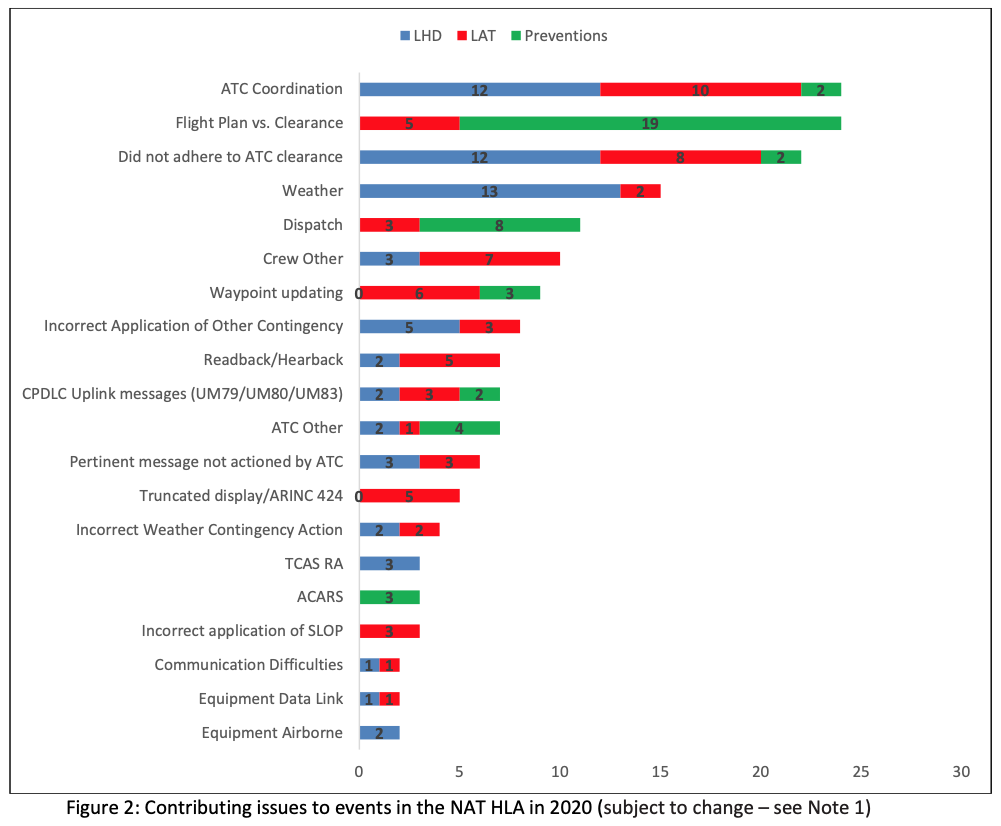

The FAA will change their definition of GNE’s

On 5 Nov 2020, the US FAA will change their definition of Gross Navigation Errors to mean anything more than 10nm (down from 25nm), to align with ICAO’s 10nm definition that currently exists on the NAT HLA. So after this date, the FAA will require you report all lateral errors, 10nm or greater worldwide.

More on this from Guy Gribble at International Flight Resources:

“Keep in mind that ATC does not always advise a crew that it files a report; therefore, the FAA inspector will try and contact the crew as soon as possible so the crew will remember details of the event. ATC keeps voice and communications records for between 30-45 days. New York Radio and San Francisco Radio keep voice communications for 30 days. The FAA directs that oceanic error investigations should be complete within 45 days of the incident.”

GPS technology allows modern jets to fly very accurately, too accurately it turns out sometimes! Aircraft can now essentially fly EXACTLY over an airway/track laterally (think less than 0.05NM), separated only by 1000FT vertically. A risk mitigation strategy was proposed over non-radar airspace to allow pilots to fly 1-2 nautical miles laterally offset from their track, randomly, to increase flight safety in case of any vertical separation breakdown.

GPS technology allows modern jets to fly very accurately, too accurately it turns out sometimes! Aircraft can now essentially fly EXACTLY over an airway/track laterally (think less than 0.05NM), separated only by 1000FT vertically. A risk mitigation strategy was proposed over non-radar airspace to allow pilots to fly 1-2 nautical miles laterally offset from their track, randomly, to increase flight safety in case of any vertical separation breakdown. Here are some interesting

Here are some interesting  It was 2004 when SLOP was adopted in the most congested non-radar airspace in the world, namely the North Atlantic.

It was 2004 when SLOP was adopted in the most congested non-radar airspace in the world, namely the North Atlantic. Consider some best practice advice:

Consider some best practice advice: Our friend Eddie at

Our friend Eddie at