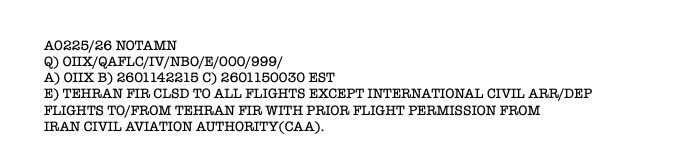

Navigating the airspace of the Middle East has become a major headache for international operators.

In recent times, risk to civil aviation in the region has changed at a pace we have never seen before.

Transits are now faced with a common conundrum: it no longer seems to be a simple question of ‘is this route safe?’ but instead, of one’s own appetite for known risks.

There simply is no ‘risk-zero’ route available.

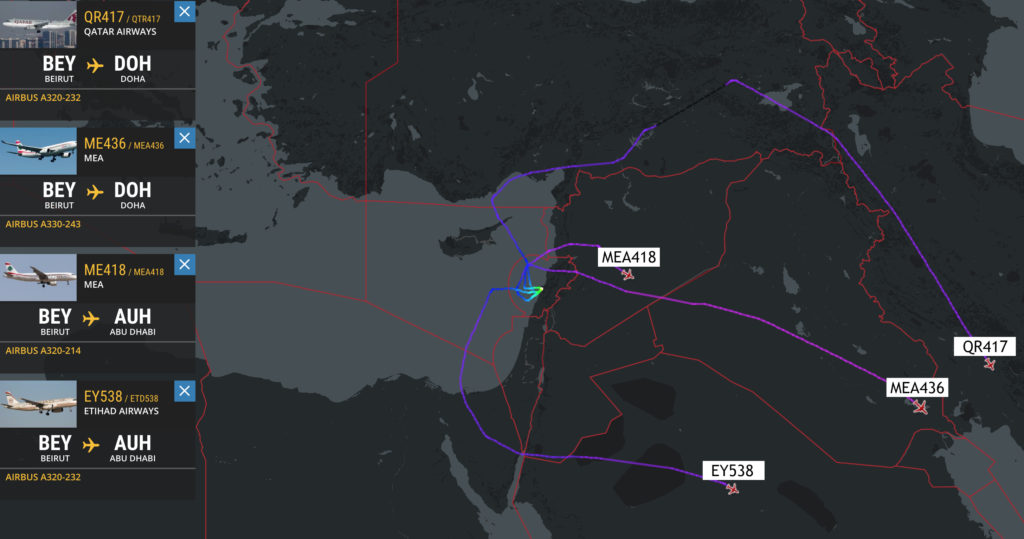

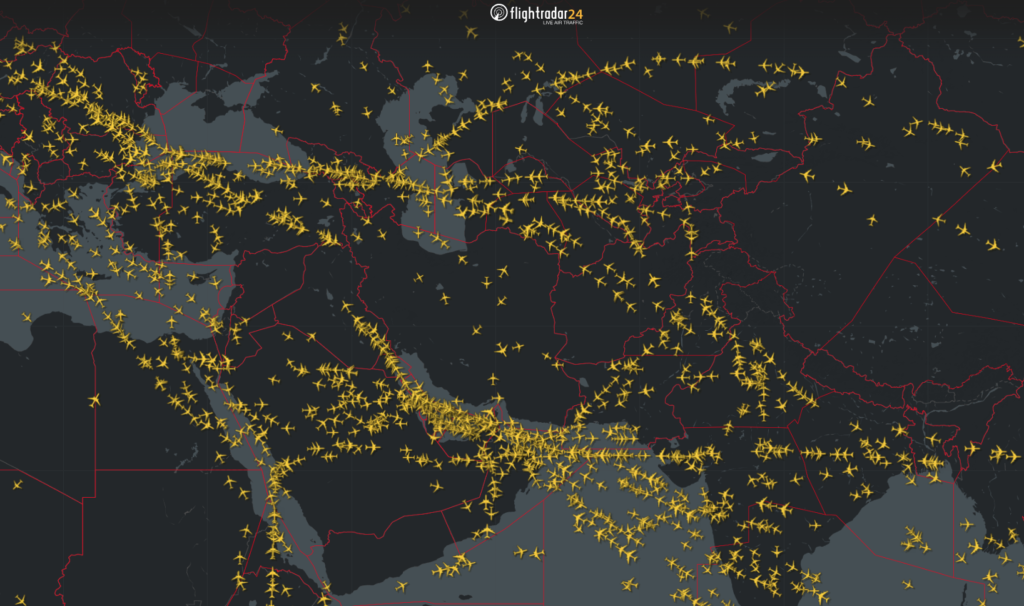

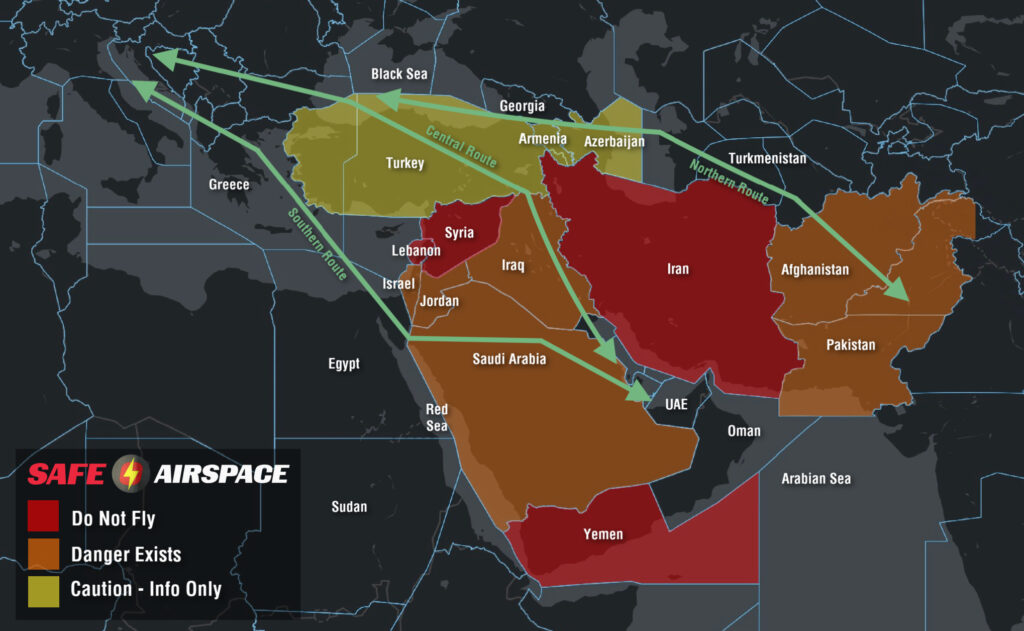

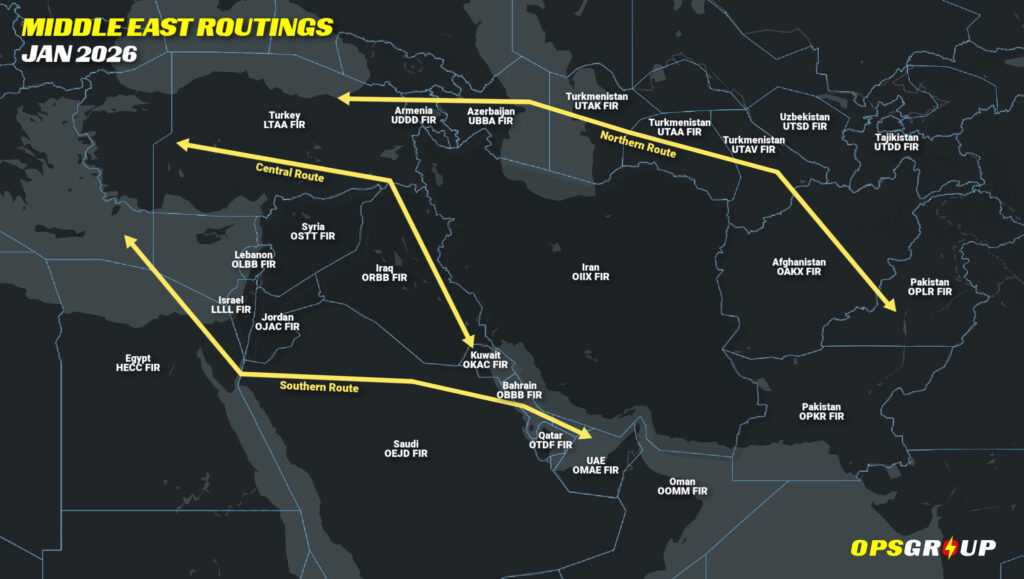

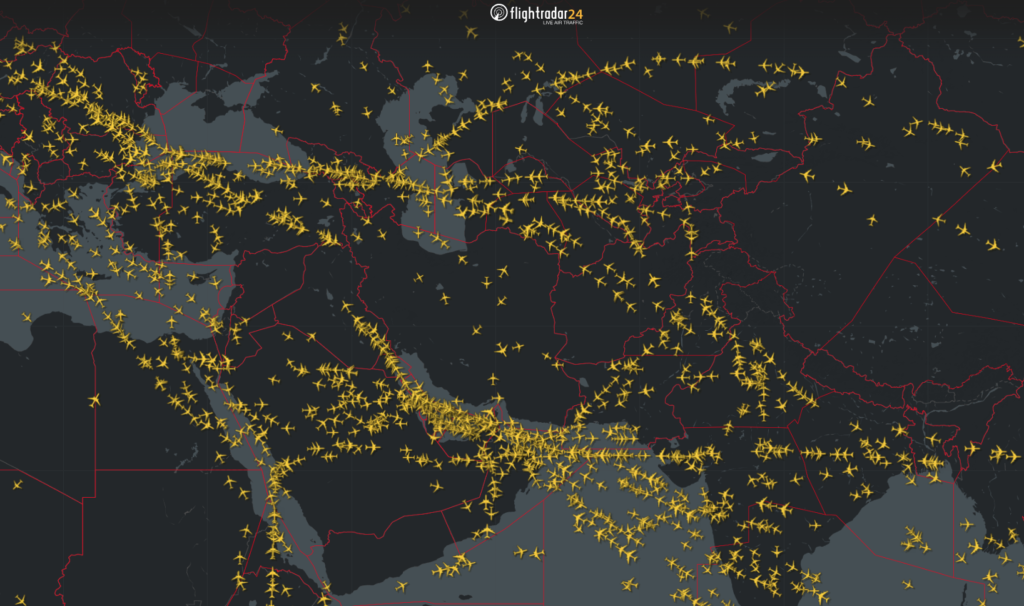

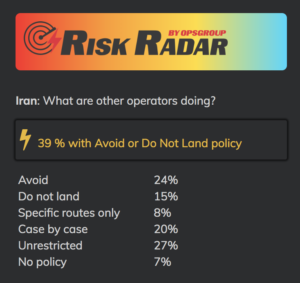

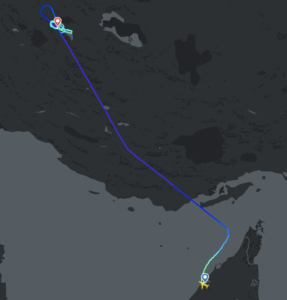

Therefore, a common question that bizav operators are asking OPSGROUP is ‘what are the major airlines doing?’ A snapshot of flight tracking right now shows that Middle Eastern transits are managing risk through the use of three distinct routes:

- South via Saudi Arabia and Egypt

- Central via Eastern Iraq and Turkey.

- North via the Stans and the Caspian Sea.

This article provides a brief risk profile for each of these routes to help operators carry out their own risk assessments when choosing a route to fly.

A Note About Risk

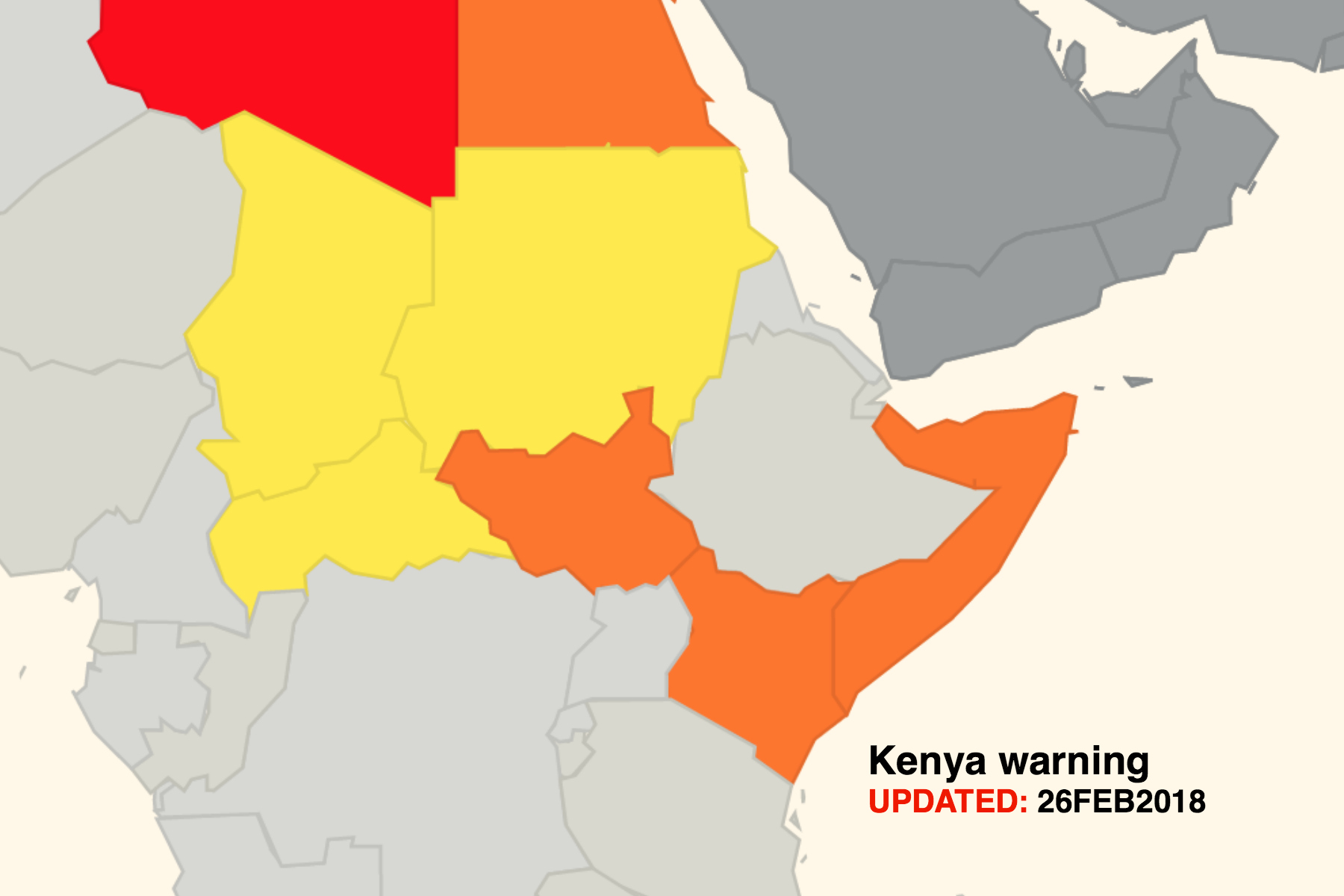

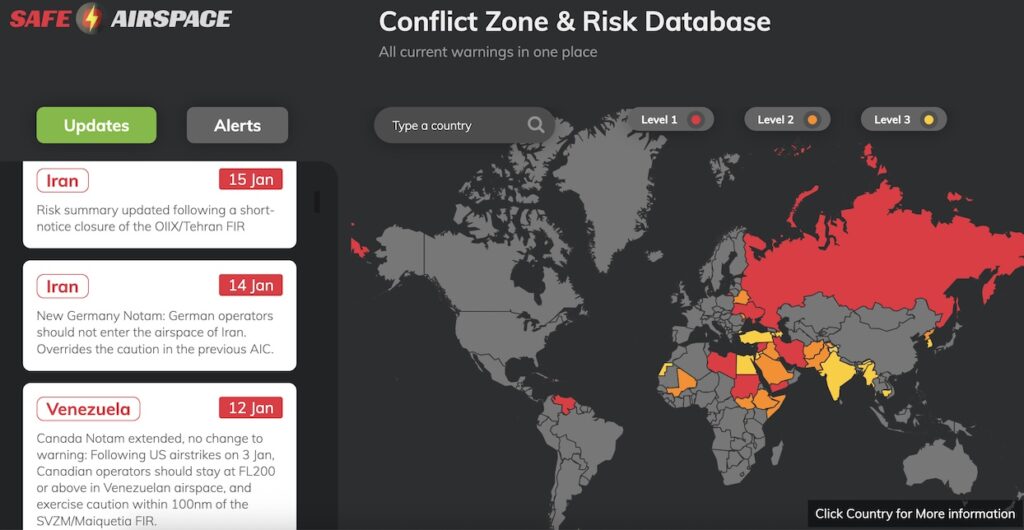

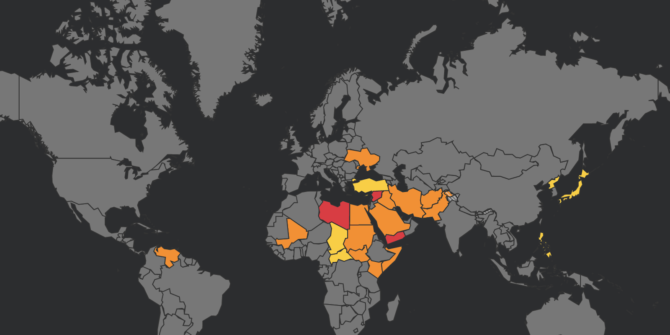

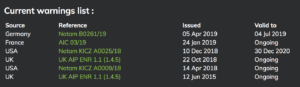

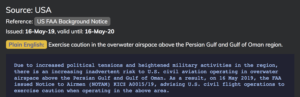

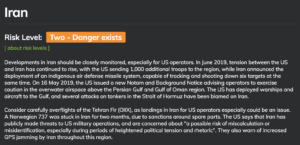

OPSGROUP also runs safeairspace.net – a database of all state-issued airspace warnings, along with risk briefings for each country in plain simple English.

We take into account both official advisories, recent and past events, advice from other specialists and potential for emerging risk when making a risk assessment.

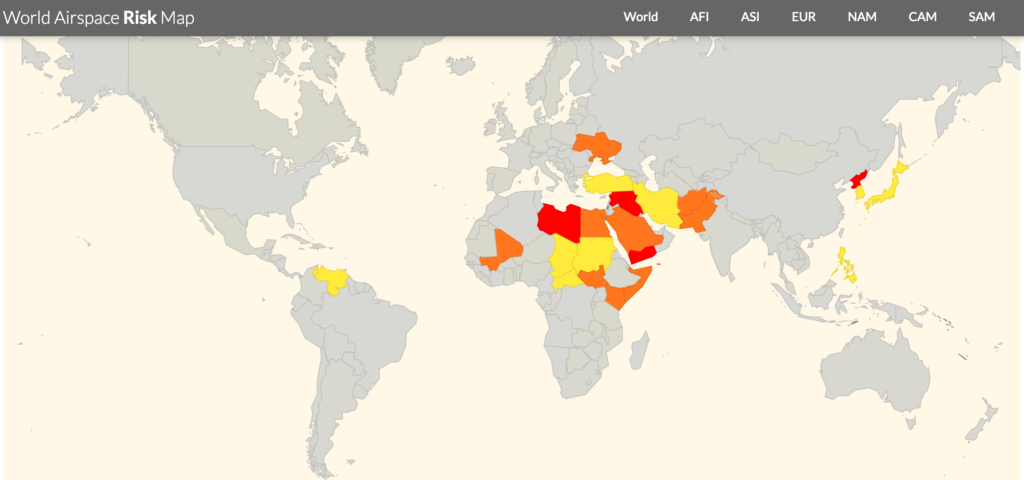

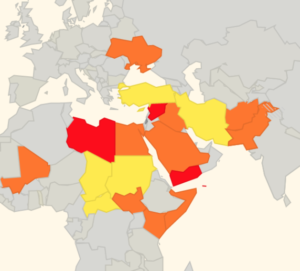

To keep things simple we have three levels:

- Level 1 Do Not Fly (Red)

- Level 2 Danger Exists (Orange)

- Level 3 Caution (Yellow).

None of the three routes above enter any country’s airspace we have classified as ‘Do Not Fly.’

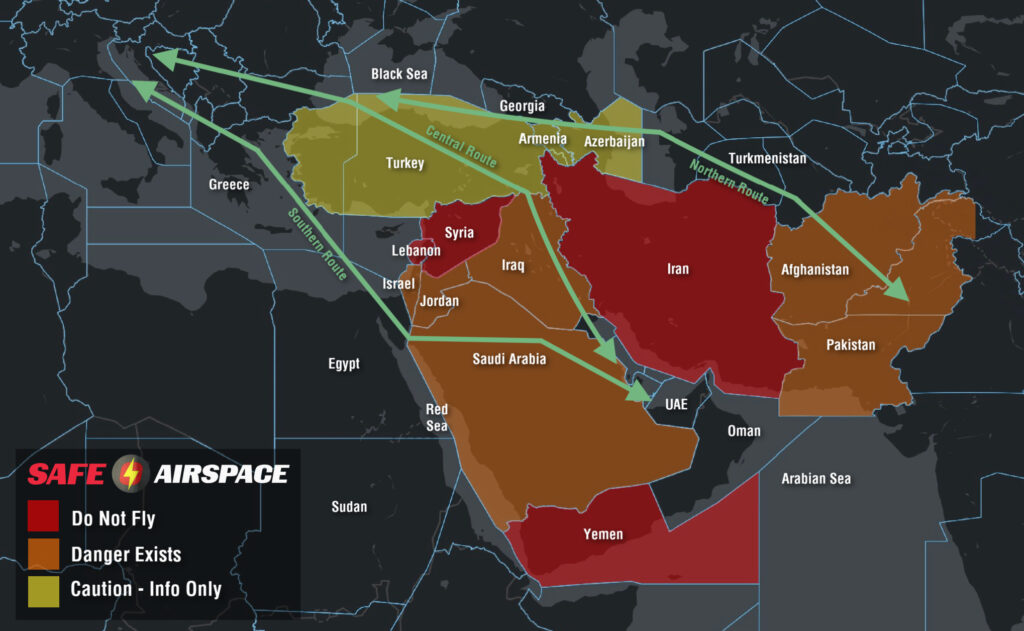

For the rest, you’ll see the map below is color coded according to the same risk profile.

The Southern Route

This route begins with a lengthy crossing of Saudi Arabia, steering clear of Israeli and Lebanese airspace to the north before crossing the Red Sea into Egypt.

It’s considered advantageous because it keeps tracks miles down (compared to the Northern Route) and avoids the potential for a sudden escalation of hostilities between Israel and Iran.

From a contingency perspective, it also provides safer diversion options than a transit of Iraq.

But now for the more-risky stuff.

The Houthi Campaign:

There is currently heightened risks to civil aviation in this area.

Houthi Rebels in Yemen are currently engaged in a long-term campaign to use missiles and drones to target Israel (therefore infringing the Jeddah FIR) along with shipping channels in the Red Sea.

The military response to these activities is the use of air defence systems to destroy them.

The latest incident occurred on Nov 3, where a crew witnessed the interception of a missile at a similar level in open airspace near Jeddah. OPSGROUP members can access a special briefing on this latest event here.

Of particular concern to aircraft at altitude is the use of ballistic missiles which originate from Western Yemen and are destroyed by defensive intercepts while on descent toward their target – which puts the airspace of Northern Saudi Arabia at heightened risk given its proximity to Israel and Gaza.

This essentially creates three risks to overflying aircraft – a direct hit by a missile (extremely unlikely), debris fields from inflight break ups or successful interceptions, and misidentification.

For the latter, many well-known incidents affecting civil aviation have come from mistaken identity. Malaysia 17, Ukraine 752 and Iran Air 652 were all due to misidentification.

Egypt ATC Congestion:

OPSGROUP has received several recent member reports of severe frequency congestion in the Cairo FIR apparently due to ATC overload.

One crew even reported that during an entire portion between the North Coast of Egypt to the Red Sea (MMA – M872 – SILKA) that they were unable to talk to ATC.

The corridor is much busier than usual which may present latent threats. Good airmanship at this time would be to keep a close eye on TCAS, ensure all anti-collision lights are on and consider the use of a PAN call if a deviation becomes necessary without a clearance.

We have approached both the Egyptian CAA and ANSP for feedback and have yet to receive a response. If you have experienced this yourself in the HECC/Cairo FIR, please get in touch with us at team@ops.group.

The Central Route

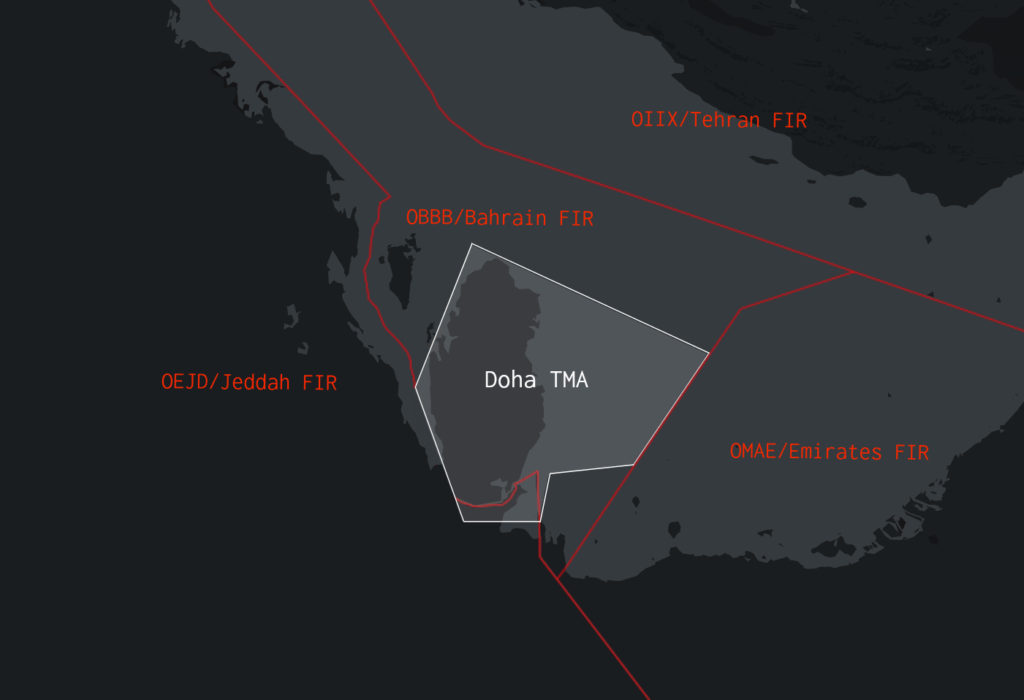

This more conventional route tracks northwards along the Persian Gulf before an extended transit of Eastern Iraq using the UM860 and UM688 airways which run parallel to Iranian airspace before crossing Turkey and a southern portion of the Black Sea.

The overriding question from this route is “is it safe to overfly Iraq?”

In our opinion, yes but with some disclaimers.

UM860/UM688 Airways:

The UM860/UM688 have been considered safe for a long time. And prior to 2021, remained the only option available for US operators to enter the Baghdad FIR at all.

They continue to see heavy traffic by major carriers and can be considered a viable option.

When using them, an important consideration is their proximity to Iranian airspace. Due to the recent escalation in hostilities between Israel and Iran, many states prohibit operators from entering the Tehran FIR due the risk of anti-aircraft fire at all levels.

Extensive GPS interference (including spoofing) can be expected in Northern Iraq and on at least one occasion has led an aircraft to almost inadvertently enter Iranian airspace without a clearance.

Extra vigilance for the early signs of GPS interference is essential for the safety of this route, along with early notification to air traffic control if it is suspected. Radar vectors remain your best fail safe.

Also beware of the potential for sudden closures of the ORBB/Baghdad FIR should further fighting occur between Israel and Iran. It closed completely during recent Israeli airstrikes and remains geographically sandwiched between the two, along with Jordan and Syria.

Free Routing:

In 2021, the FAA changed the rules. A new SFAR was issued that allowed N-reg overflights anywhere in Iraqi airspace, provided they’re conducted at or above FL320, which has opened-up new options for free routing.

Great for fuel, but arguably not safety. We continue to advise against flights away from the above airways due to well publicized risks of militant and terrorist activity which may target civil aircraft with anti-aircraft weaponry.

They may also be misidentified by air defense systems targeting drones which are frequently used to conduct attacks in Northern Iraq that originate from Turkey and Iran.

Crew and passenger safety is also an important concern should an emergency landing be required.

Turkey (beware of GPS interference):

We maintain a low-risk rating of caution for Turkey. As two of the three routes in this article include a lengthy overflight of the country, it is worth touching upon why any risk rating has been applied at all.

There is minor risk to overflights from misidentification by local militia who infrequently target Turkish military aircraft with anti-aircraft weaponry. This risk is predominantly near the border with Syria and Iraq where a higher level of airborne military traffic and UAS is present.

Far more prevalent is GPS interference – there have been frequent reports of both jamming and spoofing by aircraft well inside Turkish airspace. It appears to be common throughout the LTAA/Ankara FIR, especially anywhere near the border with Iran or Iraq. PIREPs also extend to Turkish airspace over the Black Sea. Reports share very similar symptoms: Un-commanded turns, position errors, and multiple GPWS warnings. The spoofed locations tend to center on Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula – a difference of between 120-250nm from the actual aircraft position. OPSGROUP members can access a special briefing on this hazard here.

The Northern Route

This is the route being favored between destinations in Europe and India/South East Asia.

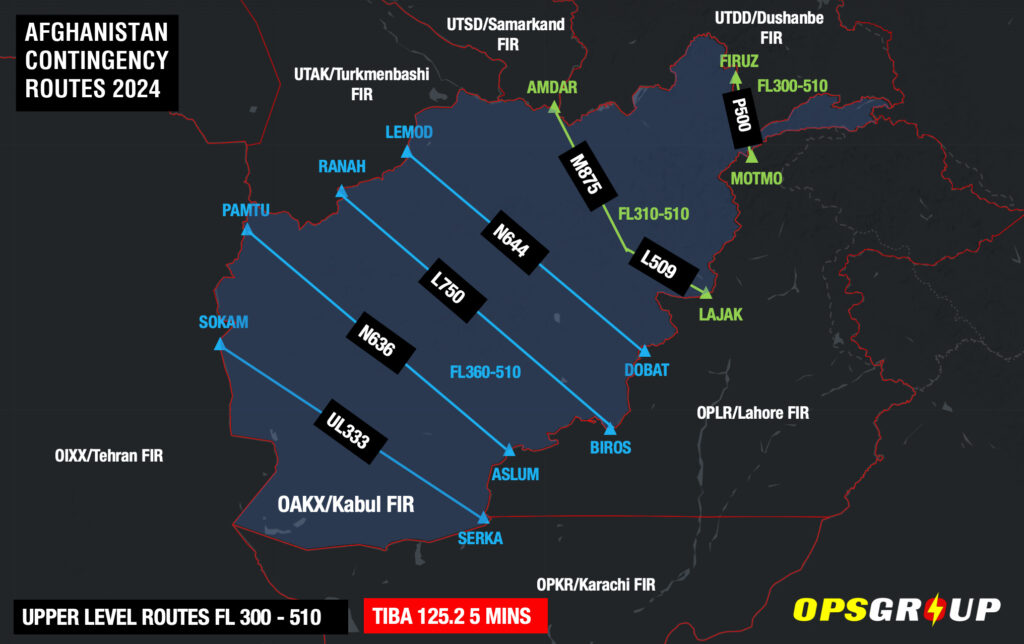

It begins with a transit of Pakistan, before an uncontrolled crossing of Afghanistan and into Turkmenistan. A westerly turn is then made cross the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Turkey before rejoining the central route over the Black Sea.

While a fairly conservative option, it is the longest in terms of track miles.

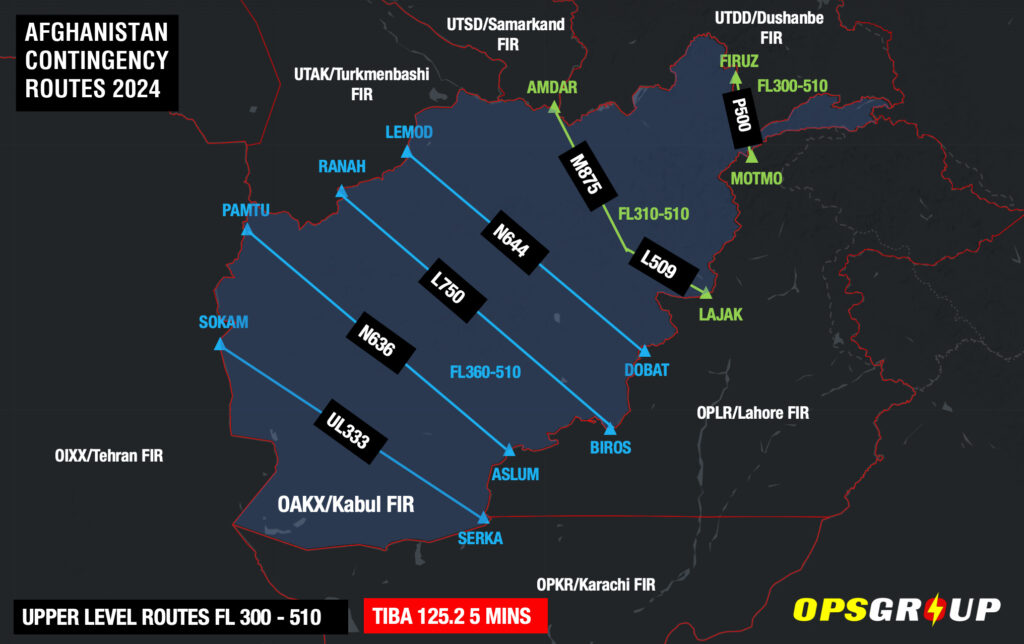

Afghanistan:

For all intents and purposes, airspace safety in the Kabul FIR has not changed since the Taliban re-assumed control of the country in late September 2021.

The entire FIR remains uncontrolled and there is no guarantee of crew or passenger safety if you need to land. In that sense it remains the most important consideration in the selection of this route.

With that said, adjacent FIRs are managing the entry and exit of traffic and separating them with miles-in-trail and level restrictions.

Once inside, fairly robust contingency procedures (including the use of TIBA) appear to be working, with major carriers the likes of Lufthansa and KLM making safe crossings every day.

Aside from potential insurance complications of extended flight in uncontrolled airspace, it seems the predominant risk for overflights is what happens if you have an emergency and need to divert.

The overriding consensus (along with common sense) is don’t land in Afghanistan. In our recent article we explained it would be wise to consider it akin to ditching i.e. a last resort. Careful consideration of critical fuel scenarios to clear the Kabul FIR in event of de-pressurization, engine failure or both is essential to moderate this risk.

Azerbaijan and Armenia:

We maintain a level of caution for overflights of these countries given their history of conflict, but for now the risk to overflights remains low.

A ceasefire agreement is in place, and most states have lifted their airspace warnings for the YDDD/Yerevan and UBBA/Baku FIRs.

When sporadic fighting has occurred, it has been confined to border regions. A contingency to keep to mind is the use of northerly waypoints BARAD, DISKA and ADEKI to avoid the area and transit from Azerbaijan through Georgia instead.

Stay Informed

The situation in the Middle East has recently proven that airspace risk can change quickly and without warning.

Overflights need to stay informed and have good contingencies in place to manage unexpected re-routes and airspace closures, along with suitable diversion airports.

OPSGROUP issues Ops Alerts for members on a daily basis, but our risk and security alerts are also available for free on safeairspace.net which our team keeps updated around the clock.

If you have more questions, you can get in touch with us on team@ops.group. We’d love to hear from you.

In the end, the aircraft was out of service for over two months, no doubt costing the airline a fortune in lost revenue. It’s unclear who will be picking up the bill for “extra” complications of getting the permits with Iran, but that will be a costly exercise also.

In the end, the aircraft was out of service for over two months, no doubt costing the airline a fortune in lost revenue. It’s unclear who will be picking up the bill for “extra” complications of getting the permits with Iran, but that will be a costly exercise also.

What are surface-to-air missiles, and who has them?

What are surface-to-air missiles, and who has them? There is some evidence to suggest that more States are starting to provide better guidance and information to assist operators in making appropriate routing decisions, but we think this still has some way to go.

There is some evidence to suggest that more States are starting to provide better guidance and information to assist operators in making appropriate routing decisions, but we think this still has some way to go.

These MEA overflights are of interest. The airline is a member of the

These MEA overflights are of interest. The airline is a member of the