Even with today’s levels of planning, monitoring and onboard safety systems, aircraft are still managing to land at the wrong airports, crew are still mistaking one runway for another, and even (occasionally) heading to the wrong country entirely.

Here is a look how and why these rather embarrassing, and potentially dangerous mistakes happen, and how to avoid them.

Wrong Runway.

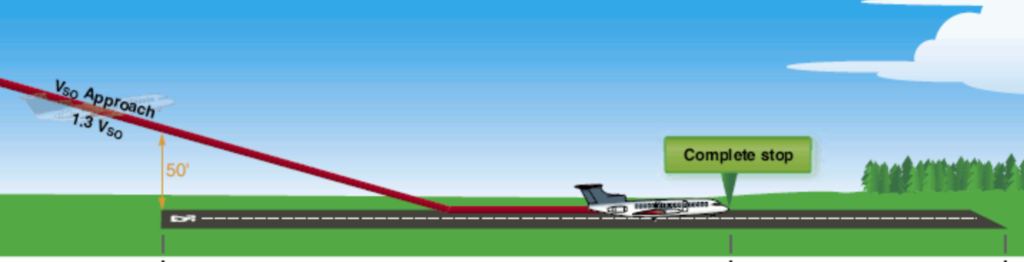

Landing on the wrong runway is a hazardous event which poses a major traffic collision risk. It also has potentially big performance implications and by that we mean the chance of a runway excursion.

EASA Safety Information Bulletin 2018-06 looked at reports filed by European operators between 2007 and 2017 and found 82 occurrences of aircraft landing on the wrong runway. An average of 8 a year might not seem high, but the consequences of an aircraft landing on the wrong runway could be catastrophic so even one is really one to many.

*Thankfully* the majority of incidences occur in visual flight conditions and are a result of visual illusions or misidentification during visual approaches and side step manoeuvres. So, instances of crew just aiming at the wrong runway.

While ‘being visual’ might mean a traffic collision risk is lower, the risk of performance issues and runway excursions remains high.

There are numerous airports worldwide which present a risk due to their runway orientation, approaches and prevailing conditions. KJFK/New York’s Carnasie approach has seen several an aircraft incorrectly establish inbound for runway 13R instead of 13L following the inbound turn, particularly when there are crosswinds which affect the “picture” (the runway doesn’t appear in the window where you expect it to).

There are also instances of mistaken clearances. Like the one that took place in July 2020.

United Airlines flight UA57 was on finals for runway 09L at LFPG/Paris Charles de Gaulle when ATC incorrectly cleared them to land runway 09R. The crew, used to sidestep procedures in the USA, failed to query the clearance which was unusual for Paris and instead commenced a low level turn to runway 09R. An EasyJet aircraft already lining up on 09R for departure reported the conflict on the radio and the United Airlines flight initiated a go-around from 260 feet AGL.

While an initial investigation into this has raised probable causes primarily resulting from the ATC mental slip, a sidestep at that altitude should be a visual manoeuvre. The crew of the United Airlines should have spotted the aircraft already on a runway which they were turning towards at 300 feet. The FAA have released a new SAFO related to this.

So being visual does not always reduce the traffic collision risk after all.

Then there are the more concerning ‘not aiming for a runway at all’ events.

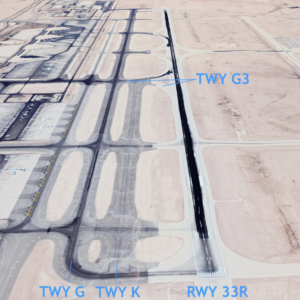

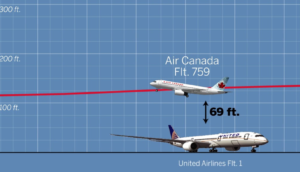

The KSFO/San Francisco Air Canada incident in 2017 is a serious example of visual cues going wrong. The Air Canada A320 was cleared to land runway 28R. However, they had missed a Notam advising that runway 28L was closed and, expecting to see an open runway to their left, mistook 28R for 28L and aligned themselves with an active taxiway.

The aircraft missed traffic on the taxiway by between 10-20 feet during their go-around.

In 2007, an MD-83 routing from Lisbon to Dublin was carrying out an approach at night to Dublin runway 34. There was a prevailing wind of 260/12 which orientated the aircraft heading to 336° in order to maintain the inbound track of 342°. The crew mistook a 16 storey lit building for the runway and aimed for it, carrying out a missed approach from 1700 feet (around 200 feet above the building).

TNCM/Princess Juliana airport in Sint Maarten is known for a large hotel to the left of runway which, in hazy or rainy conditions, can be mistaken for the runway due to it being more conspicuous than the runway.

Then there was the KLM crew who managed to mistake taxiway B for a runway on takeoff from EHAM/Schiphol…

So how to avoid making this mistake?

The recurring factor throughout all of these is visual illusions and incorrectly interpreted visual clues. Not looking at stuff, or not looking at stuff right.

Of course, it is easy to say that from the comfort of a chair, on the ground.

Sat in the pilot seat, barrelling towards said ground at several hundred feet per minute with everything else going on around you as well… less easy. But there are some fairly common sense methods of identifying threats and errors before they become a problem.

The FAA released SAFO 17010 following the KSFO incident. It provides some ‘best practices’ for accomplishing an approach and landing on the correct airport surface:

- Any visual approach, or visual segment of an approach, should be well briefed and monitored.

- Known risks (such as hotels that somehow look more like the runway than the runway) should be talked about. If there is a chance of visual illusions, talk about them and talk about what you expect to see.

- Think about the wind and where you will actually need to be looking in order to see the runway. It might not be straight ahead.

- Fly a stabilised approach.

- Monitor things like height, heading, to make sure they make sense. And back it all up with Navaids and other information if that is available.

Wrong Airport.

Landing at the wrong airport also happens!

One analysis found at least 150 flights by US carriers landed (or almost landed) in the wrong airport between the 1990s and 2014. Not including totally valid diversions of course.

The most common reason for wrong airport landings is down to pilot error once again – both visual and procedural.

In 2017, a Delta flight 2845 landed at the wrong Minneapolis airport. They were due to touchdown in KRAP/Rapid City, but mistook nearly Ellsworth air force base for their intended airport. Both have the similar runway orientations (although that’s really the only similarity – Rapid City has two runways which possibly should have been a giveaway).

In 2006, a Ryanair flight aiming for EGAE/Londonderry-Eglinton ended up landing at a military base in Ballykelly 5 miles away, again just due to a misidentification of the airport.

Ethiopian airlines suffered two near embarrassments when two of their airplanes both tried to land at the wrong airport in Zambia. Actually, one of them did. Destined for Ndola, both mistook the new (and unopened) Copperbelt for their destination airport.

The fix remains the same:

- Brief what you expect to see.

- Brief how you expect to get there.

- Check and monitor that other clues – navaids, waypoints, airport layout – make sense!

- A lot of airport charts also have warnings on them when there is another airport nearby which has been known to trick pilots in the past. Look out for these.

- Many aircraft have systems which monitor their position in relation to what you told it (in the box) you were going to fly it. If your airplane is beeping, blaring or swearing at you then it is trying to tell you something – don’t ignore it!

Are these just embarrassing stories?

Unfortunately, there is a much more serious side. The wrong airport might be a commercial, logistical problem, but the real big risk comes down to that runway performance again.

Of the 150 or so near/actual landings at wrong airports which took place in the US since the 1990s, there were 35 actual landings and 23 of these occurred at airports where the runways were shorter than those at the intended destination.

In 2014, Southwest flight 4013 aiming for KBBG/Branson airport accidentally touched down at KPLK/Clark Downtown airport instead. Branson’s runway is 7140’. Clark’s is 3738’.

A Boeing Dreamlifter made a similar error when routing to McConnell Air Base but instead touched down at Jabara airport, on a runway only 6,101 feet long.

The critical safety issue here is the performance – the fact it hasn’t been checked and that it might not therefore be, well, ok.

And if it is happily ok, then you might still be looking at a bit of an issue getting the airplane back out again. Much like our Dreamlifter friends found out.

Wrong Country.

Finally, wrong countries. A much rarer occurrence but possibly the most embarrassing should it happen.

A British Airways flight (in all fairness it was actually a German aviation business operating on behalf of BA) managed to fly to EGPH/Edinburgh instead of EDDL/Düsseldorf after a paper work mix up had the crew sent totally the wrong flight plan.

However, since the flight was planned and fuelled for Edinburgh this only really impacted the rather put-out passengers.

A potentially more serious incident happened in 2015 when an Air Asia crew had to divert back to Melbourne, Australia, after the pilot incorrectly input the route from Sydney to South Africa instead of WMKK/Kuala Lumpur.

Given the fairly different direction you have to wonder how far they got before they, or ATC, spotted something was up?

Fancy a bit more reading?

NASA have a handy analysis on visual traps that is worth a read.

Check out the FAA’s project on ‘runway surface events’ here – including some info on the ASDE-X project which uses surface radar to detect when an aircraft might be lining up on a taxiway for departure.

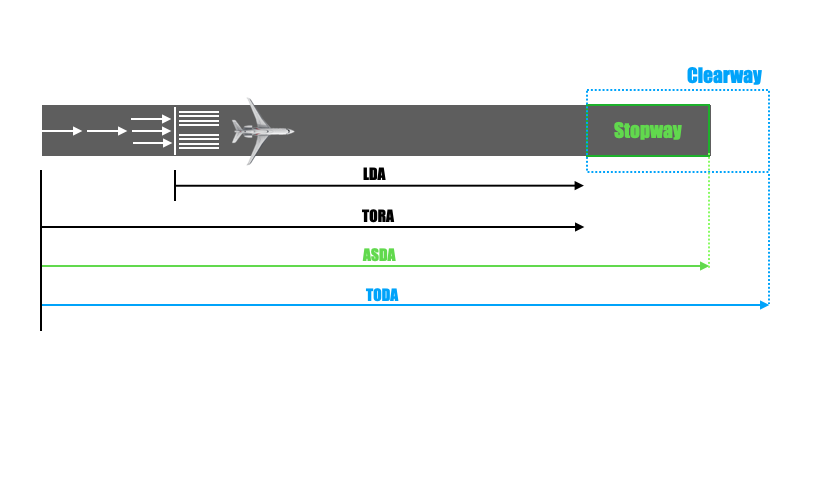

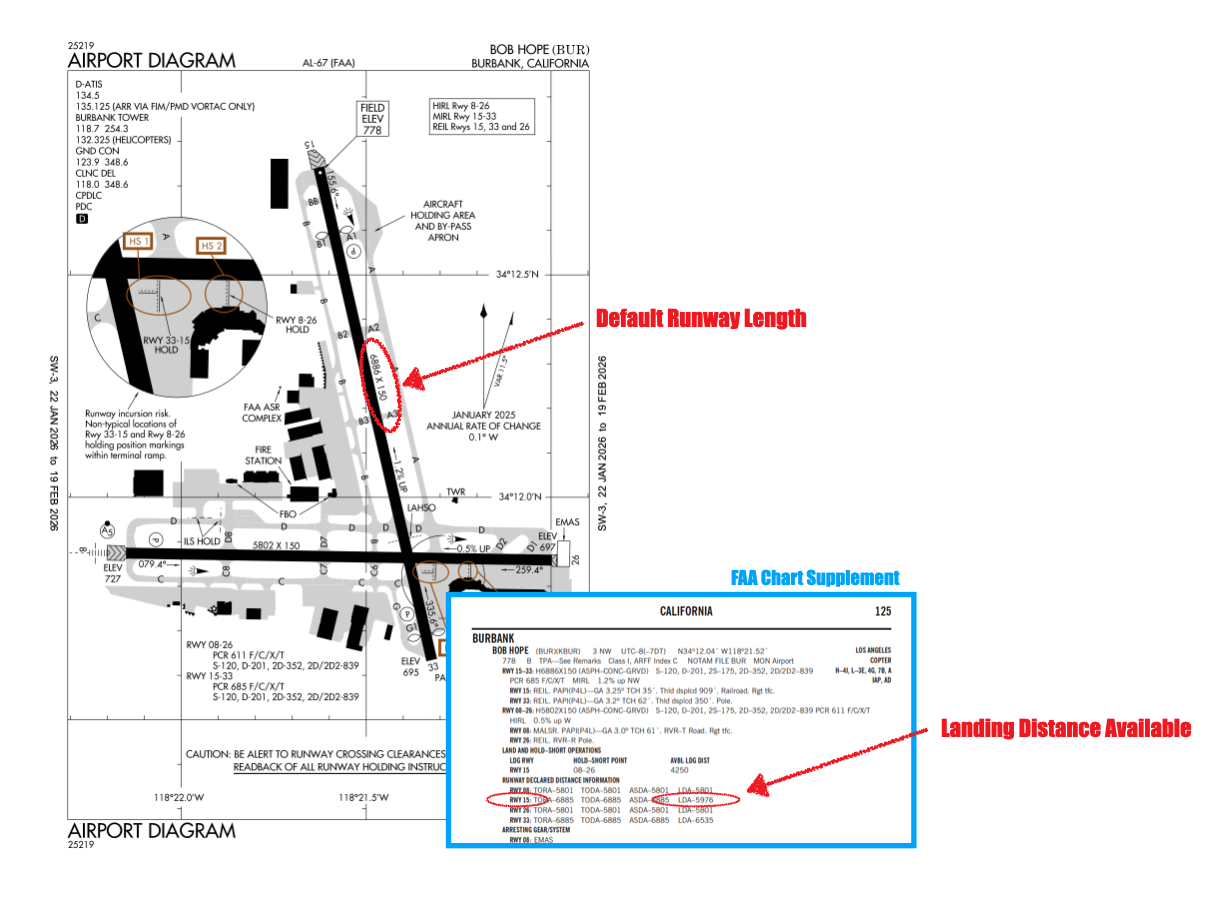

Under the FAA regs, these distances are the authoritative performance numbers. They override any single runway length shown elsewhere. That’s the key point.

Under the FAA regs, these distances are the authoritative performance numbers. They override any single runway length shown elsewhere. That’s the key point.

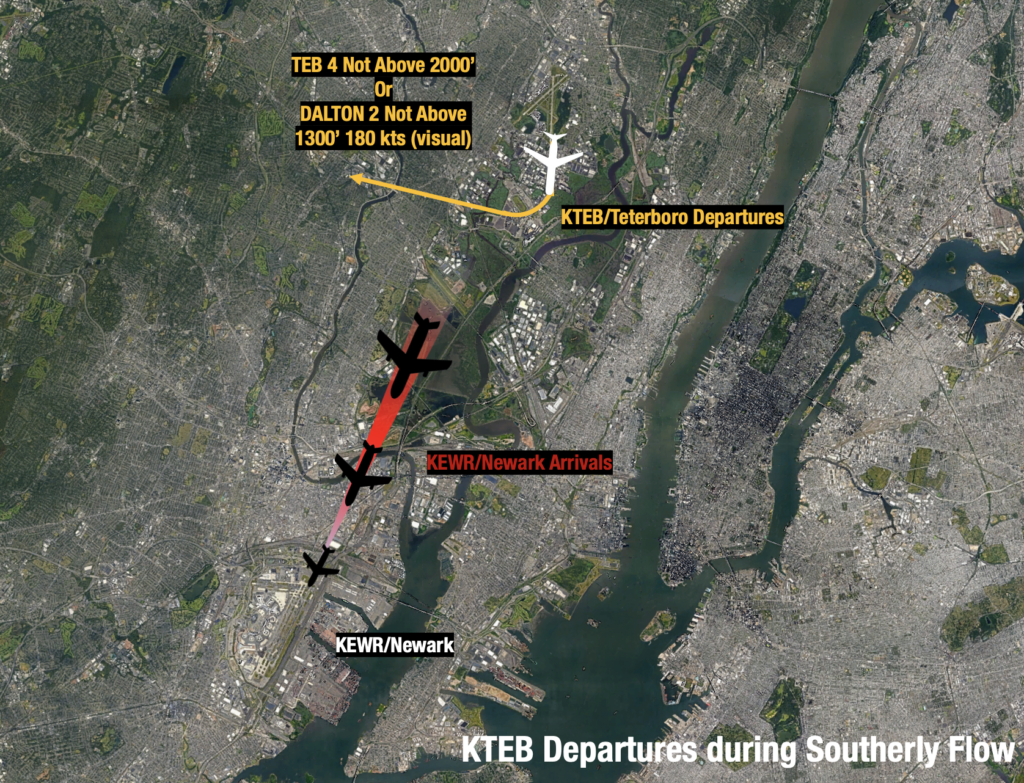

Runway 19 Departures (Southerly Flow)

Runway 19 Departures (Southerly Flow) Teterboro isn’t the only option.

Teterboro isn’t the only option.

There have also been more than a few “incidents” of aircraft from

There have also been more than a few “incidents” of aircraft from

A better NOTAM may have been:

A better NOTAM may have been: In another serious incident associated with these runway works,

In another serious incident associated with these runway works,