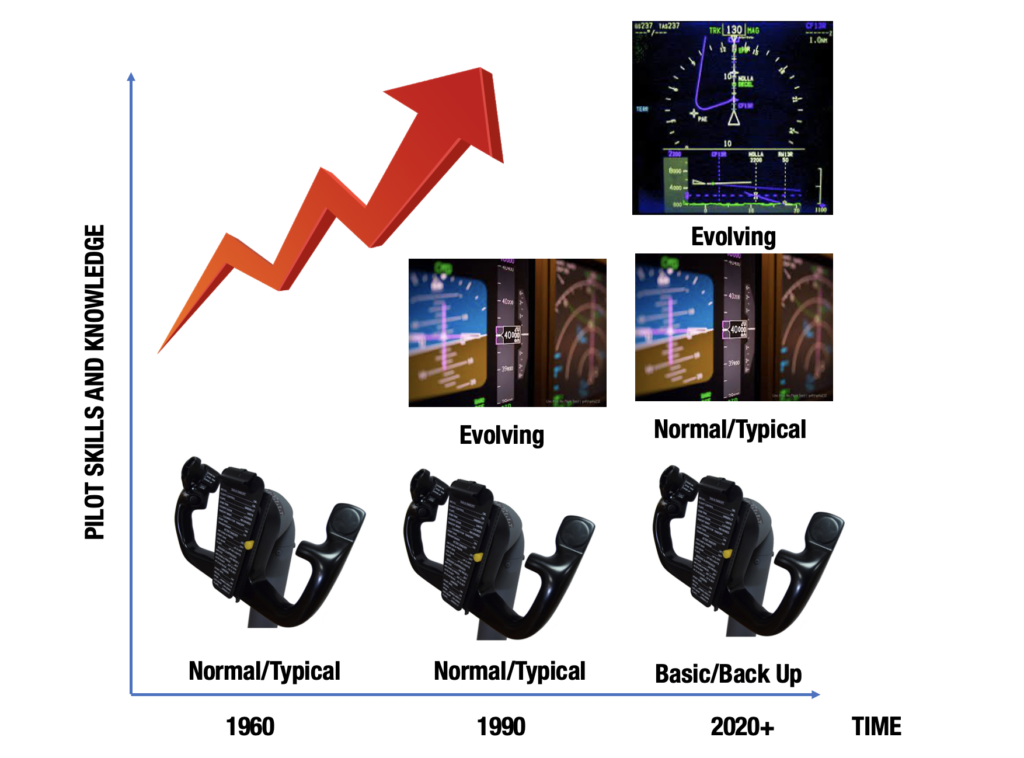

Over the past decades our industry has undergone an automation revolution.

Basic autopilots from eras-past were little more than wing levellers. Today they are sophisticated computers capable of awe-inspiring accuracy.

The industry has welcomed automation with open arms. And it’s no surprise. The vast majority of aviation accidents are caused by us, humans. Mechanical failure on the other hand only accounts for less than a quarter of all accidents.

So for operators and manufacturers alike the benefits of automation are clear – safety and efficiency. We are simply not as predictable or consistent as a computer because we are human. And automation has become a major line of defence.

But herein lies the problem…

It’s easy to see that a pilot’s role in the flight deck has changed forever as we interact with higher and higher levels of automation. Some might even argue that we are being progressively designed out of the cockpit completely and to some extent this may be true. Whether we like it or not, full autonomy is coming. Take the Xwing Project for instance – their concept can be retrofitted to conventional aircraft enabling them to fly without a pilot.

But right now the more pressing issue is that our role continues to transition more and more from flying airplanes to managing automation. Put it this way. A recent study found that across a large sample of flights aboard the Airbus A319, pilots were spending on average only 120 seconds manually flying each flight. And that was the middle of the curve.

This creates a unique set of risks that the industry collectively needs to better address.

The majority of time we spend flying is through panels like these.

Good Automation

By no means is this an attempt to detract from the positive impacts that good automation continues to have in our skies. The benefits are no secret. When used as intended it is a huge work-load reducer. It allows us better flight path control and liberates us from repetitive and non-rewarding tasks – something humans are known be no good at. We become less fatigued and have more capacity to deal with other things.

It also works in unison with systems like ECAM and EICAS to better help us manage things when something goes wrong.

Automation has also improved the skies we fly in. Fantastic things like RVSM and PBN have allowed us to fly closer together and make better use of crowded airspace. While around the world minimas grow ever closer to the ground thanks to things like RNP approaches where automation can help us ‘thread the needle’ in some one the world’s most challenging approaches.

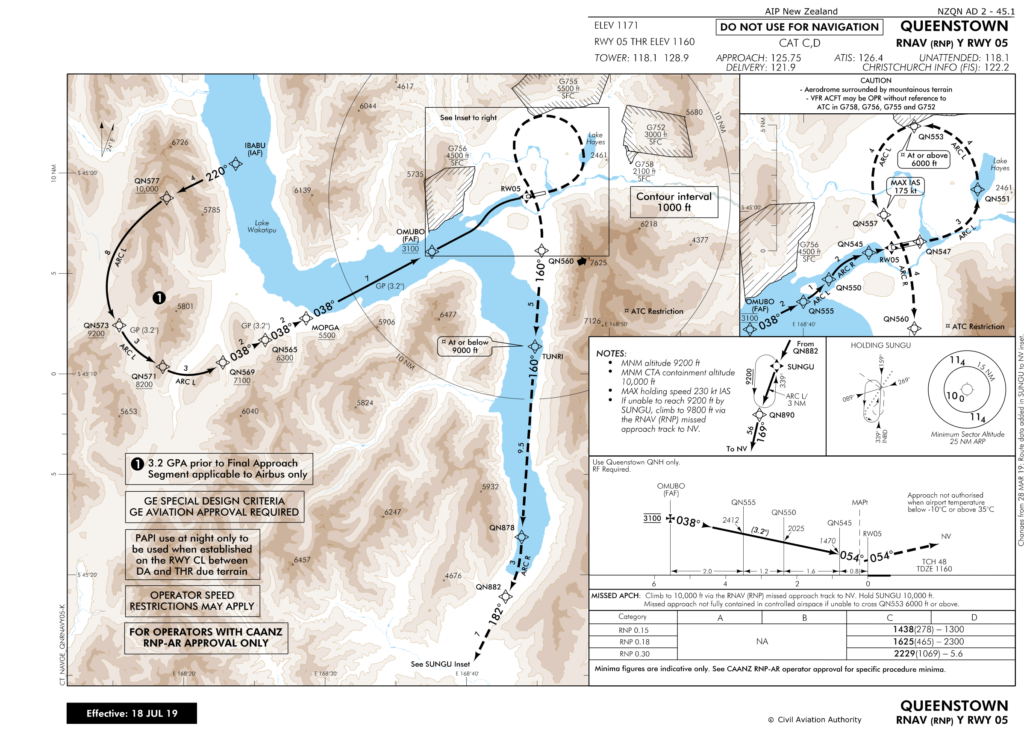

Take Queenstown for example. The notorious airport down in New Zealand boasts beautiful scenery but a reputation amongst pilots as being one of the most demanding in the world due to the intimidating terrain that surrounds it. RNP approaches have dropped minimas from over 3000 feet off the deck to less than 300. And now you can land there at night.

Threading the needle at Queenstown – check out those spot heights.

Bad Automation. Here is where things start to go wrong.

All positives aside, automation is also having an effect on us pilots. And it is important to remember just that – we are still pilots. We must never lose the ability to fly without automation. Back in 1997 the late and well-respected Airline Captain Warren Vanderburgh saw it coming and coined the phrase you are no doubt familiar with – Children Of The Magenta Line.

This remains true to this day. If we become too reliant on automation, avoidable accidents happen. Here’s why.

It Erodes Skills.

Slowly but surely automation is chipping away our manual and cognitive flying skills. You know the ones – your stick and rudder. We are being actively encouraged to keep automation on and control our trajectory through it. Do that for long enough and we begin to forget how to do it the other way – with our hands, eyes and feet.

It Distracts.

Because we are so used to flying our airplanes through automation, when something unexpected happens such as short notice changes from ATC our immediate response is to try and figure out how to make the automation accomplish it. We go heads-down precisely when we should be going heads-up – and the clock is ticking.

It Confuses.

Chances are if you have operated anything with high levels of automation, at least once you’ve uttered the infamous phrase “what’s it doing now?”

And yet still we are reluctant to turn it off. As soon you identify that the aircraft is not going where it should, that’s your cue to intervene. The minute you don’t, you are simply along for the ride. Pilots around the world would agree, this is never good enough.

Mode confusion is another. Modern automation features many different ways of achieving the same outcome, but with subtle and sometimes dangerous differences. We need to understand the limitations of each one because if we don’t, we know that tragedies can happen.

A little known incident in Australia serves as a good example. Snowbird, an Airbus A319, was on approach at YMML/Melbourne airport on a clear calm evening. A tired but highly experienced crew were flying an unremarkable STAR and ILS approach at the highest level of automation. All was going well until the pilot flying reached up to arm the approach in a dimly lit cockpit. He pressed the wrong button. Over the next 39 seconds chaos ensued.

What followed was a series of rapid fire mode changes, confusion and attempts to salvage the approach through the automation. Three EGPWS warnings were triggered and an altitude alert issued by the tower as the airplane reached just over 1,000 feet off the deck at 315 kts before they regained their situational awareness and executed a missed approach.

After the incident neither pilot could recall exactly what happened, what modes they had engaged and neither had heard any of the EGPWS warnings. The automation had performed flawlessly throughout by providing the crew exactly what it was told to do. When it all went wrong, it seems the pilots were reluctant to turn it all off.

Snowbird. A great example of when good automation goes wrong.

It Startles.

Automation is designed to give you back control when something goes wrong. For crew our first indication is usually a loud aural alert and a flashing red light. For systems that seem to operate flawlessly flight after flight, day after day, the affect can be startling.

Pilots are suddenly given full control because we are supposed to be the ultimate fail safe.

We are not even supposed to be there unless we can fly our aircraft manually without hesitation. But the problem is we are not used to flying manually anymore. We are used to flying through automation, so when it’s suddenly not there it’s like going back to school.

There have been a number of instances where pilots have been faced with failing automation and have been unable to keep the aircraft flying safely using manual control.

Air Asia Flight 8501 is a good example. To get rid of a nuisance alert the crew pulled a single circuit breaker to one of the aircraft’s flight control computers. As an unintended consequence the autopilot disconnected and the aircraft transitioned into a degraded mode of flight where the automation was no longer available and flight protections were removed. It had done what it was designed to do – hand back control to the pilots.

Tragically the pilot flying, startled by having to fly manually in a degraded mode, stalled the aircraft from straight and level flight. The crew never managed to regain control.

The accident aircraft of Air Asia Flight 8501 – a sad reminder on how the sudden loss of automation can lead to tragedy.

As an industry our approach to how we interact with automation has to change.

Automation dependency is not a new issue. But as automation becomes more sophisticated and complex we have to continue to manage how we interact with it.

It was never intended to replace our core skills and abilities as aviators, only to better support them. Like the image below our core ability to fly manually is supposed to be a constant.

Credit: Flight Safety Foundation

But there are some ways to help.

SOPs. They must be flexible enough to allow pilots to turn the automation off when it is appropriate. You have to give pilots the freedom and confidence to use their hands and feet. Six months between sim sessions is too long.

Training. Evidence based training is revolutionising our sim sessions. There is opportunity there to encourage manual flight. To turn it all off without warning and give us the much needed confidence back.

Monitoring. We need to encourage active monitoring so that we can intervene quickly if we need too. We should always be mentally flying the plane even if an autopilot is flying. One way to do this is by keeping our hands on the controls during dynamic phases of flights. It is a tactile reminder that we are still in control and can take over at any stage.

Practice. It makes perfect. It’s what we got into this game for. When conditions are right and workload low, take the opportunity to turn it all off. It’s right there waiting for you again if things get busy.

Automation is here to stay.

What matters is how we use it. We cannot allow it replace our abilities to fly an airplane without it because for the foreseeable future we will still be the ultimate failsafe.