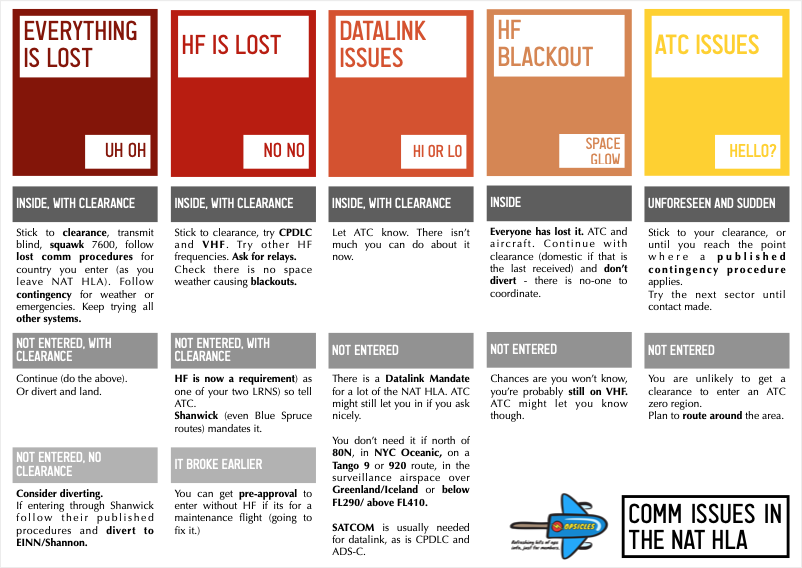

Lost comm procedures in the NAT HLA (or when you’re trying to get into the NAT HLA) are a complex and confusing thing, so here is our “Natter on the NAT” – a recap on what to do when nobody wants to talk to you.

You aircraft has lost everything it uses to communicate.

The likelihood of every communication system you have breaking all at once is fairly minimal, and given the equipment requirements to enter the NAT HLA, you are going to have more than just VHF onboard. You will also have HF, datalink, probably SATCOM…

But if it does happen (maybe a freak bolt of mega lightning or something) then the first thing to do is still try each system, including back up boxes, and your headset for that matter.

Still no luck? Don’t panic. While you can’t hear anyone, or talk to anyone, they can all still hear and talk to each other. So you are the only uncoordinated thing out there right now. First up, let ATC know by squawking 7600.

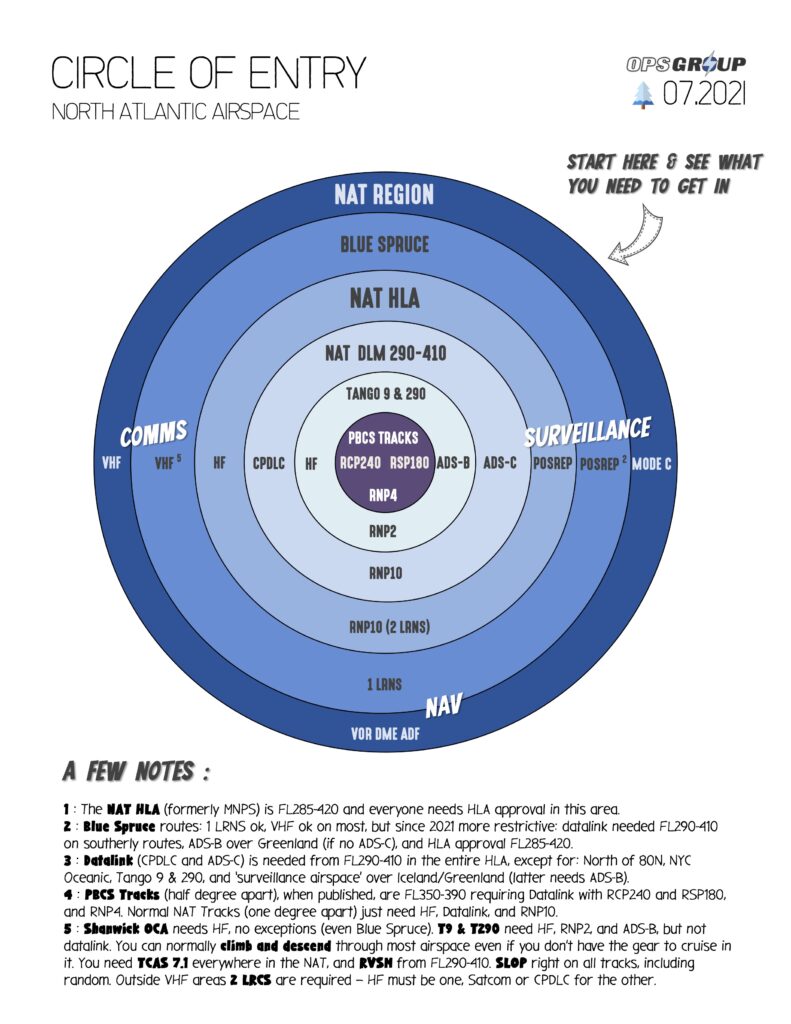

This shows the minimum equipment you need for the NAT HLA.

The next thing to do depends on where in the NAT you are.

Already in it? Great, simple. You already have a clearance and you already know where you are going, so carry on as you are, transmit blind, and once you exit follow the lost comm procedures for the place you are entering.

Not in it, but have a clearance? This is up to you really. You have your clearance (and have confirmed it) so ATC know that you know that they know that you know what you are cleared to do. So if you want to stick to in and head on in you can, but you are going to have to maintain your speed, level etc all the way through. And if you have a weather issue or an emergency you are also going to be on your own.

No clearance yet? This one is a bit tougher. It probably isn’t the best plan to head in (following your flight planned route), especially if you are heading into Shanwick. Shanwick have diversion procedures in place to take you to Shannon and the best idea might be to head there and get yourself fixed.

The exact wording is “it is strongly recommended that a pilot experiencing communications failure whilst still in SHANNON FIR/UIR/SOTA/NOTA does not enter SHANWICK Oceanic Control Area”.

The Irish AIP have the procedures for comms failure if planning on entering and they are worth a read. They have a pretty handy summary of what to do for Shanwick in there.

It is unlikely you will ever lose every system. Check backup boxes and attempt contact via other methods.

You have lost HF

If you’re already in, there isn’t much you can do. Stick to your clearance and keep in contact on CPDLC. Remember, HF frequencies are pretty rubbish at the best of times so if you discovered the failure while trying to make an HF call, then try a different frequency.

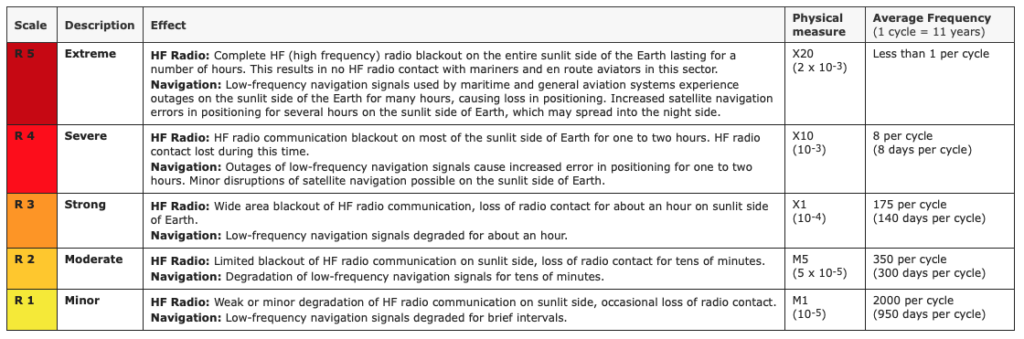

Lower ones work better at night, higher ones by day, and always try the middle ones for good measure. Have a quick glance at space weather too because if there are geomagnetic storms forecast it could be there is a general HF blackout going on that is affecting everyone.

Collins Aerospace publish a daily list of HF frequency assignments for their side (the US side) of the North Atlantic and you can find them here. Worth a look before you fly, if you’re going to be in the US North Atlantic area.

The Comms requirements changed a bit in February 2021, and basically, what they say, is that you need two long-range comms systems if routing anywhere outride VHF coverage. One of these has to be HF.

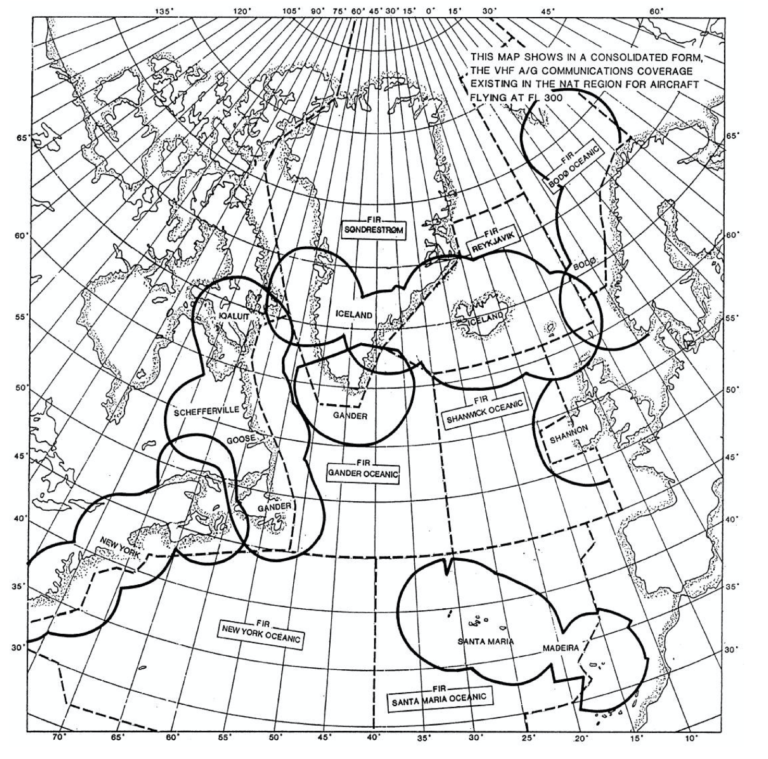

Here is a particularly horrible picture of where VHF has got you covered.

If you’re flying at FL300, this is your VHF coverage.

You can route through if your HF was already broken and you told ATC in advance (Item 18 on the flight plan) and they gave you the thumbs up, but if you are heading there and it goes suddenly before entry then you are going to need to talk to ATC.

Shanwick OCA needs HF, no exceptions (not even the Blue Spruce routes that fall within the Shackwick OCA) so don’t go diverting immediately but do get talking (on whatever else you have available) to sort it out before you enter.

We might as well cover HF blackouts while we’re here.

These happen when space weather happens. They aren’t super common and they are usually minor (lasting 10 minutes or less). But when they do happen, everyone can lose HF, including ATC.

You probably should make position reports on 123.45 to be on the safe side because there might be no coordination between traffic and ATC for the period of the blackout. Keep trying different methods to get hold of ATC as well (but don’t get all crazy at them though – they will be busy and will contact you when able).

Now, because coordination between ATC and everyone else is an issue, they actually don’t want everyone diverting all over the place, so stick with your clearances. The big point here is – if you don’t have a NAT clearance yet, you need to stick to your DOMESTIC clearance. That means you have to stick with what you were most recently told to do, not what you filed for on your flight plan.

The NOAA scales – anything above R1 or R2 is rare.

Datalink problems.

So your texting system is on the blink? Unfortunately, the Datalink Mandate is in force now so you need this to enter. If you ask ATC nicely (and have everything else working) they might still let you in.

You don’t need it if you are north of 80N, in NYC Oceanic, on Tango 9 or 290 route, or in the ‘surveillance airspace’ over Iceland/Greenland. So if you can re-route via any of this, that might be a good plan. Otherwise you do also have the option of flying above or below the NAT HLA (so below FL290 or above FL410) if your aircraft (and your fuel) can do that.

Remember, datalink uses CPDLC and ADS-C so if either of them is broken, your datalink probably is as well.

SATCOM

Most datalink systems also require SATCOM – so while you don’t need it to use it, if your aircraft needs it for the Datalink to work, then what we said above applies.

Let’s talk ATC – Strikes.

An ATC strike is *usually notified in advance. The chances of them walking out without warning is fairly remote. So if you know about it beforehand, plan accordingly. If it happens while you’re there, treat it as an ATC Zero event.

ATC Zero.

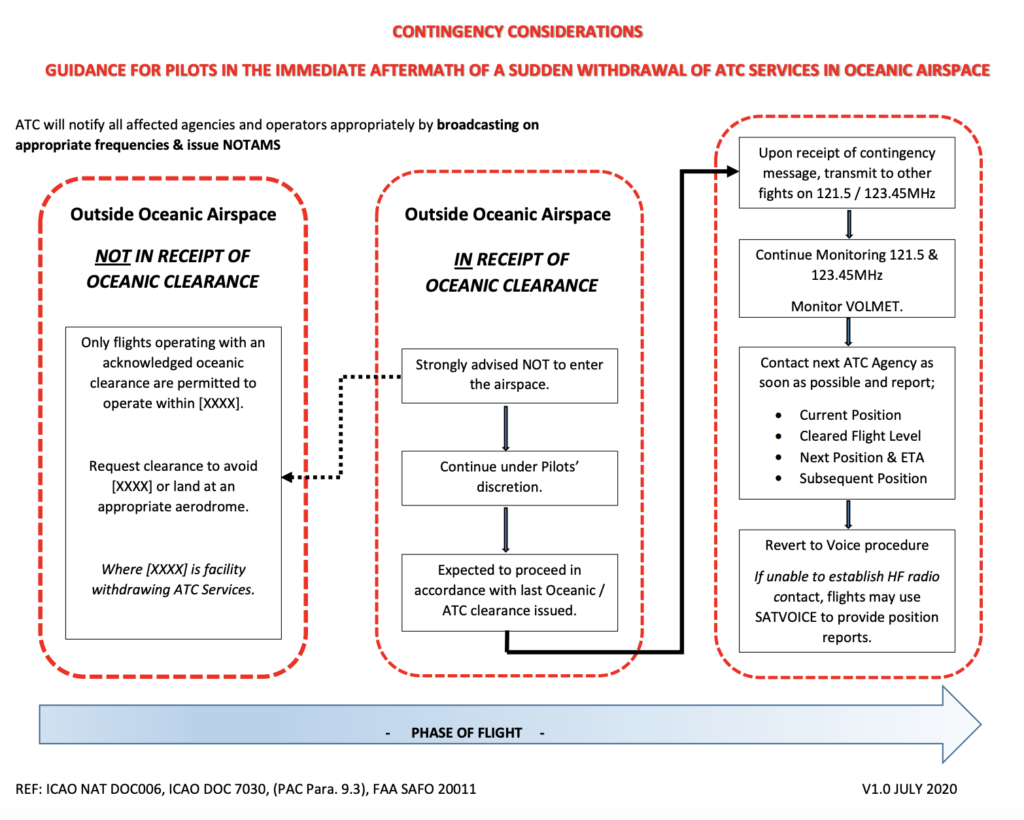

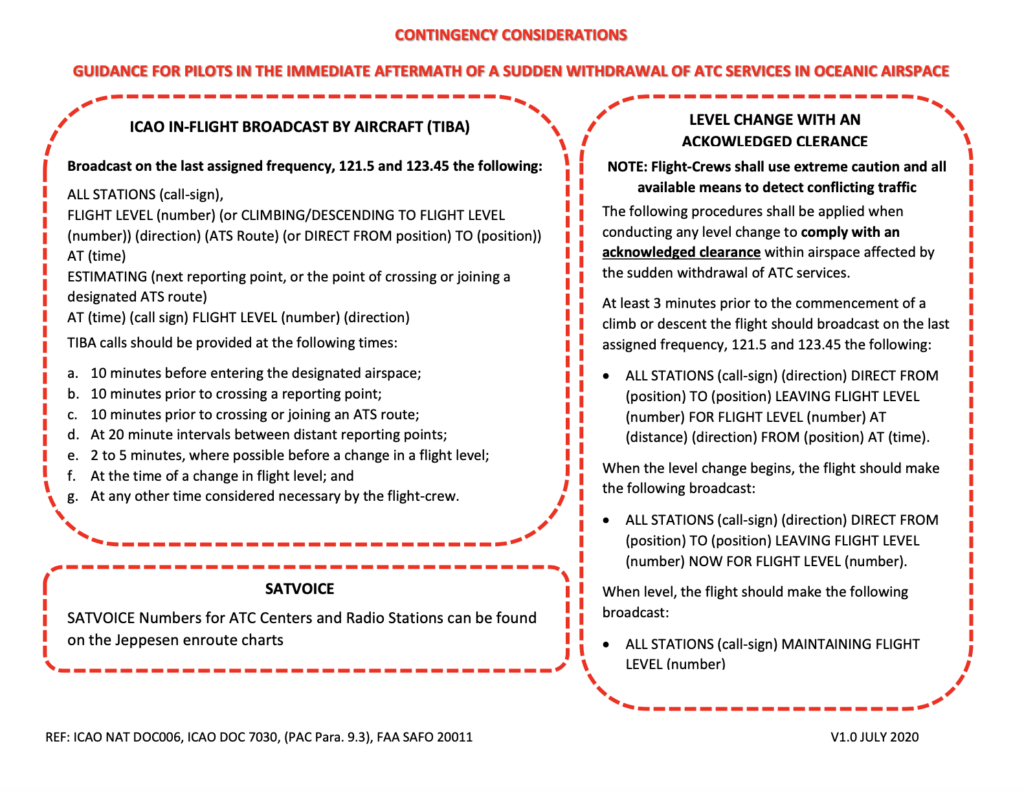

There is no-one out there. Maybe they had to evacuate? There was some sort of emergency or major technical issue that’s has taken down an entire ATC provider? Occasionally it is Notam-ed, but in that case you won’t have been given clearance to head through, so we are talking those unforeseen sudden zero events.

Each region has its own contingency procedures which you can find in their AIP, or better still in NAT Doc 006, which was also updated in Feb 2021.

These routes are really for when big stuff happens – the entire ATC for a sector is evacuated for example. In most cases, other units will try and manage control as best they are able, but it will be fairly limited.

So, if you’re already inside, continue and start trying to make contact with the next sector (as they will hopefully be managing control as much as they can). If it is a big ATC zero event you are probably going to have to follow the contingency routes to exit the NAT HLA (rather than your clearance) but this will be ‘activated’ by whichever ATC is taking over control.

If you already have your clearance to enter you can, and you can transmit position reports on 123.45, but it is not really advisable. The best plan is to organise a re-routing.

If you don’t already have a clearance then you aren’t going to be able to enter the ATC zero bit and you will need to plan a re-route around the affected sector.

Feeling the need to read more?

Here are some handy links to things on the subject.

Changes to NAT Doc 006 – our blog post summarising what these were.

The Irish AIP (again) in case you missed the link earlier.

The GOLD Manual (2017 edition) – for all your Datalink info.

Opsgroup Member?

Then click here to download our handy little Comms Issues on the NAT “Opsicle” – a refreshing bit of ops info, just for members.

If you’re not an OPSGROUP member, but you’d like to be, you can join here.