On August 2, the US Department of State updated its worldwide terrorism warning for the first time since 2019 – terrorist groups around the world may be actively planning attacks on US interests. This follows news on July 31 that the leader of a major terrorist organisation was killed during a military operation in Afghanistan.

My flight is tomorrow, what does this all mean?

For starters, no new airspace warnings have been issued due to the recent events. But it is equally important that operators (especially N-registered ones) heed the information that is already out there.

This comes from a combination of FAA SFARs, KICZ Notams and Background Information notes.

In the most dangerous airspace, the FAA bans US operators at all levels. In which case, the decision to overfly is an easy one because it has already been made for you. You just can’t do it.

But it’s not always that clear cut. Risk may be present, but not enough of it to justify closing entire pieces of airspace. So the FAA carries out assessments and decides on what precautions operators should take to stay safe.

This is where the lines start to get a little blurry because these assessments take time, and security risks can evolve more quickly than the papers can be signed. In other words, what was safe yesterday may not be safe today.

And so operators may need to re-evaluate their exposure to known risks, based on what is happening right now. With that in mind, here are some hotspots US aircraft are permitted to overfly that we think deserve a second look.

Iraq

Back in October, the FAA lifted its long running Notam barring US operators from entering the ORBB/Baghdad FIR. The SFAR is now in effect, meaning overflights are technically okay provided you stay above FL320. But just because you can, doesn’t mean you should.

Militant groups are active throughout the country and are known to have access to anti-aircraft weaponry. The have also have a proven track record of targeting US interests in the country. Scour through the OPSGROUP archives and you’ll see report after report of rocket, drone and mortar attacks on ORBI/Baghdad along with other regional airports.

Our advice hasn’t changed – avoid overflights at all levels if possible. Although the eastern airways UM860, UM688 and UL602 are frequently used and considered safe options by some major carriers.

Militant groups have been known to target aviation assets in Iraq – like this empty aircraft that was damaged by a missile attack at ORBI/Baghdad in January this year.

See: SFAR 77, Background Info Note.

Mali

The FAA currently advises US operators to use extra caution if overflying Mali below FL260. The main issue is the ever-fragile security situation on the ground. The FAA cites extremist or militant groups that may actively target civil aircraft with various weapons.

And things seem to be getting worse. On July 29, the US Embassy ordered the urgent departure of non-emergency US Government employees due to the risk of terrorism. Which is a warning sign for us that these risks may be escalating.

See: KICZ Notam A0009/22, FAA Background Information.

Somalia

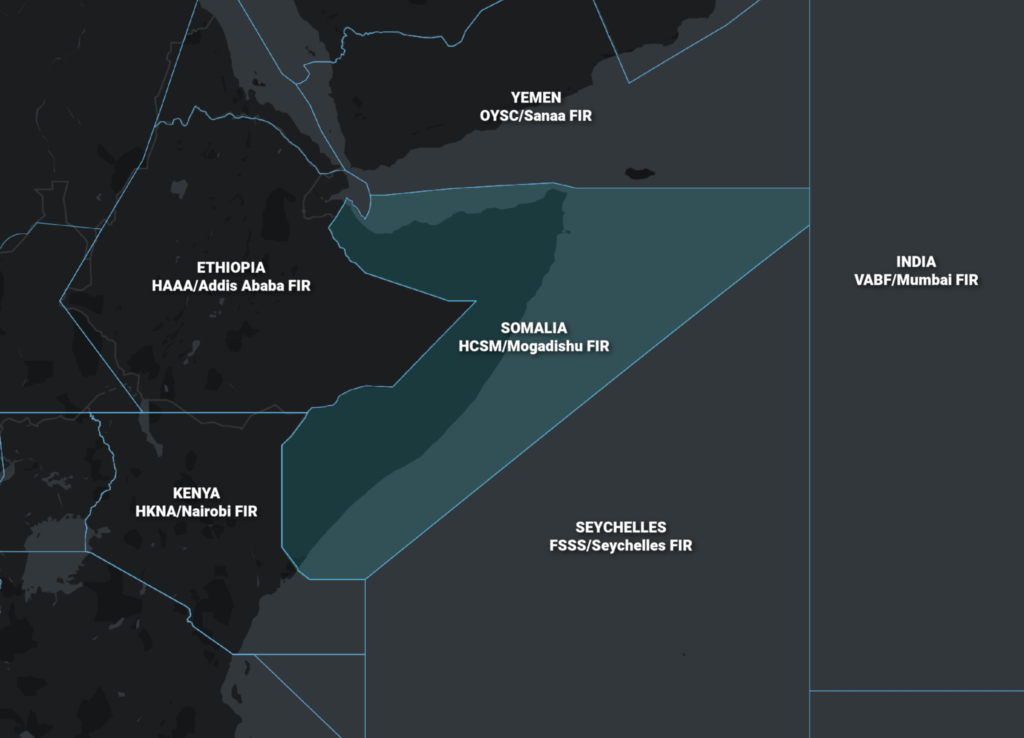

The FAA currently allows US operators to overfly the HCSM/Mogadishu FIR above FL260. It’s important to remember though that the security situation on the ground there is unstable – especially since a controversial election back in April.

Terrorist groups are active in the country, and may have been motivated by recent events. These groups have a proven track record of targeting civilians and aviation interests. In June this year news broke that several local carriers were considering suspending flights over security concerns onboard aircraft and at airports.

There is also currently an active trial of Class A airspace throughout the Mogadishu FIR, which means Somalia may be seeing higher numbers of overflights than normal. The problem is that emergencies and diversions may put aircraft at risk, especially US-registered tail numbers.

The entire HCSM/Mogadishu FIR currently has Class A coverage – the problem is security if an aircraft needs to divert.

See: SFAR 107, KICZ Notam A0028/19.

Egypt

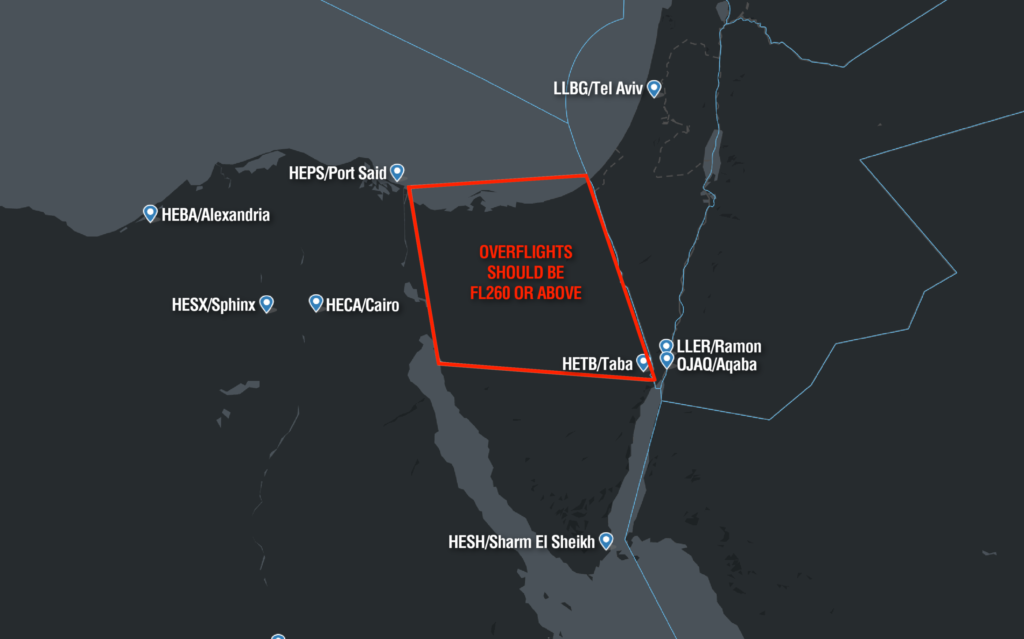

Back in March the FAA lifted its airspace warning for the HECC/Cairo FIR. It previously advised operators to stay above FL260 over the Sinai Peninsula – in the east of the country dividing the Red Sea from the Med.

The issue was the presence of extremist groups who may attempt to target civil aircraft. It’s not clear what improvements led to the warning being lifted, but other countries have kept theirs in place – including the UK and Germany.

Recent events have proven that all is not well. An attack in Western Sanai in May this year was one of the most significant in the past two years – and was a clear indicator that terrorist groups are still active in the region. If they have been motivated by the happenings in Afghanistan, this may put aircraft at renewed risk.

The UK and Germany warn operators to avoid overflights of the Sinai Peninsula below FL260

Where else to look.

As things change, airspace warnings get updated. For US operators the starting point is here – it contains everything officially put out by the FAA.

There’s also safeairspace.net – our conflict zone and risk database. The OPSGROUP team keeps this updated as new information comes to hand. You can view a global risk briefing by clicking here.