There is a recent history in the US of serious incidents that have occurred during visual approaches – you don’t have to hunt long to find them. The reality is this: when we accept a visual approach, we accept more risk.

That isn’t to say that this risk cannot be effectively and safely managed. Visual approaches are still an important way to increase the efficiency of congested airspace. But we do have to give ourselves the room, the capacity, and the mitigations to fly them safely. And in my opinion, that’s where the true risk lies.

The FAA seems to agree. On April 2, it issued an eye-opening Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO) regarding visual approaches. The lowdown is this: visual approaches can be riskier than they seem, especially in today’s busy airspace. Let’s take a closer look.

FAA SAFO on Visual Approaches

The FAA’s SAFO is resolute in its message – the pilot-in-command has the ultimate responsibility (by law) to say no to clearances that excessively increase workload or erode safety margins. In other words, they don’t want us to hesitate to say ‘UNABLE’. Ultimately, it’s our decision as pilots, and no one else’s.

FAA Reg 14 CFR § 91.3 specifically says:

“…The pilot in command of an aircraft is directly responsible for, and is the final authority as to, the operation of that aircraft.”

This includes the full authority to refuse or decline any clearance or instruction that they deem unsafe or beyond the operational limits of the aircraft or crew. The SAFO then continues with another important message – ATC will support a PIC’s authority to declare ‘unable’ when a clearance may reduce safety margins.

This is where the SAFO falls short a little, at least on a real-world basis. What needs to be included is ‘with impunity.’

Recent Events

In a US NAS burdened by traffic volume, aging infrastructure and controller shortages we continue to hear reports of excessive delays and even confrontation when a clearance is declined.

Check out the recent diversion of a Lufthansa A350 at KSFO/San Francisco due to non-acceptance of visual separation at night.

Courtesy of VASAviation.

There appears to be a growing disconnect here between what the FAA wants in its SAFO, and what’s actually happening in the real world.

It’s seems clear that more needs to change amongst all stakeholders before we can begin to consistently practice ‘safety over sequence’ while accommodating all traffic.

FAA Mitigations

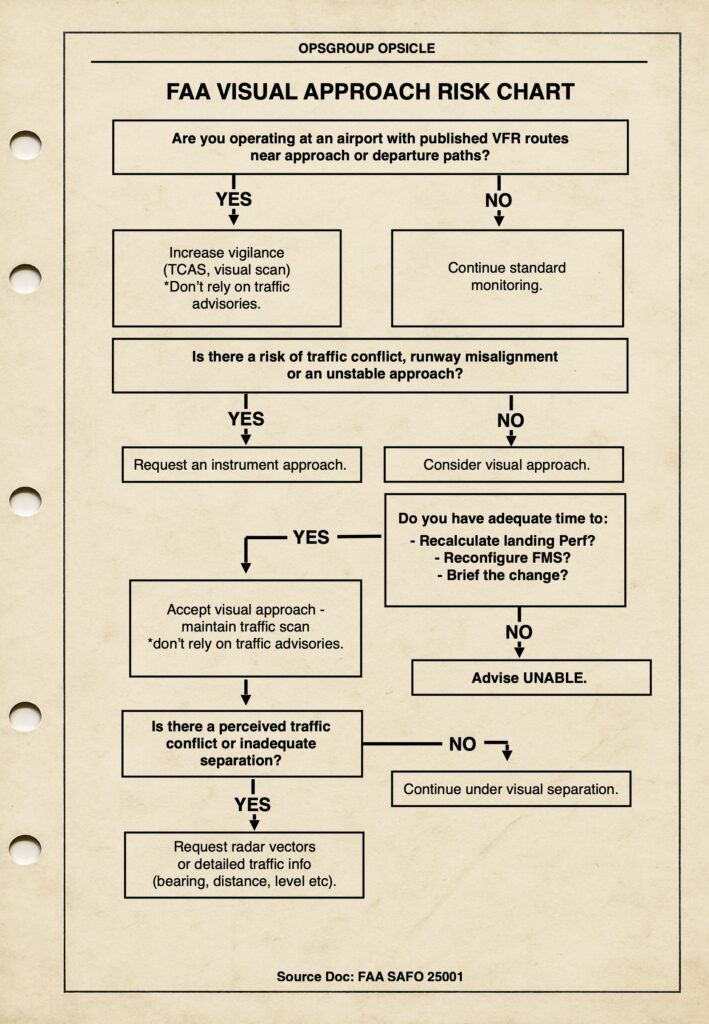

The FAA’s recent SAFO also provides some guidance for pilots on how to mitigate some of the risks of accepting visual approaches. We’ve summarized those in the following little Opsicle.

A note about Business Aviation

In researching this article, several suggestions were also raised about the human factors involved with why pilots find it so hard to say no to challenging clearances. Attend any Human Factors course and you’ll be familiar with the common culprits – saying ‘unable’ can feel like a form of noncompliance, the need to be perceived as competent, an innate desire to ‘make it work’, or the struggle of time compression.

What’s more interesting to us on this occasion is the vulnerability (when compared to airline ops) of business aviation crew to accept challenging clearances despite the increased risk. In other words, are there unique factors? BizAv pilots are faced with a unique combination of industry culture, operational demands and perception of role.

Under Pressure:

BizAv pilots usually find no solace in the anonymity of a flight deck door, a staff number, or a large airline. They have direct contact with those who employ them (sometimes even in the cockpit). Whether we like it or not, this can have an insidious effect on our tolerance for risk. Saying ‘unable’ can feel like failing to deliver.

Professional Flexibility:

Travel by private jet can typically cost anywhere between ten to forty times more than flying commercial. Those who pay may have a certain expectation that we can land anywhere, anytime and circumvent the constraints of conventional airline travel.

No One’s Watching:

Unlike the airlines, there is no requirement for business jets operated under Part 91 to be equipped with Flight Data Recorders or even CVRs, or even under Part 135 (with less than ten seats). And it is hard to deny (even with the best intentions) that this doesn’t have some kind of impact in moments of unexpectedly high workload. Strict adherence to stabilized approach criteria for instance can become more flexible without fear of reprisal.

Safety Management Under Part 91:

The FAA SAFO also specifically mentions the use of safety management systems (SMS) to better mitigate the risks of conducting visual approaches. However a looming mandate will only apply to Part 135 operations – not Part 91, where they will remain voluntary. It’s therefore possible that some BizAv pilots will not be exposed sufficiently to the FAA’s advice.

Want to join the discussion?

We’d love to hear from you. You can reach us at: news@ops.group.