IATA recently ‘urged action’ over rogue lithium-battery shippers. Folk are apparently sneaking them onboard without proper notification or packaging, and this could turn into one big, hot mess for airlines.

So, here is a closer look at Lithium Ion batteries, what they are, what they can do, and how to better deal with them onboard.

What are they?

In big terms they are things that power a lot of our airplanes. In smaller terms, they are the batteries in our phones and portable electronics.

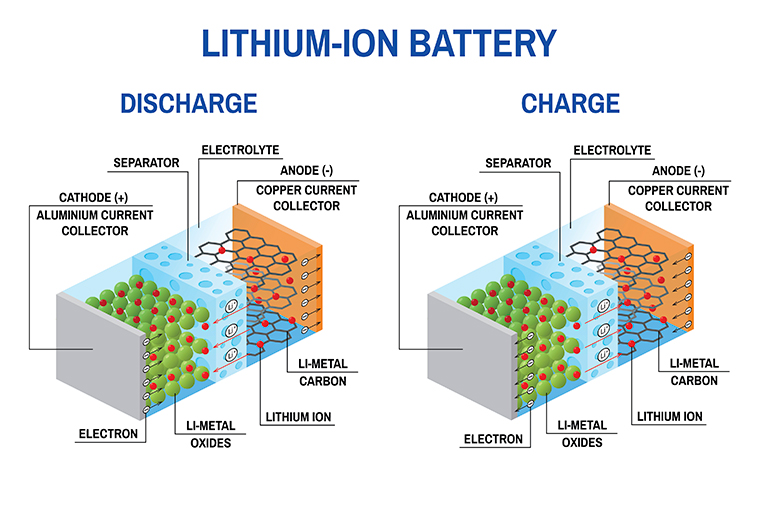

And in super simple terms (and with some creative licence thrown in) they are a cell that contains an electrolyte liquid. Lithium Ions get all charged up, and when they are feeling particularly positive, they dive into the electrolyte and swim through it. The movement of them gets the electrons all excited too, and they go zooming along from the current collector, through the device (your phone, laptop, airplane) which sucks out their charge, and then they get collected up by the negative current collector.

They are different to regular Lithium (without the ion) batteries because they are rechargeable. They also have no memory effect (they don’t get lazy when repeatedly recharged) and they have good energy-to-weight ratios.

A diagram because my explanation was not good

What is the risk?

They sometimes go into thermal runaway, usually when charging, but also if you bash them about (think iPhone stuck under business class seat, getting repeatedly run over by the chair mechanism as the passenger tries to pull it out again).

Thermal runaway, as the name suggests, involves them getting really hot – so hot it reaches the melting point of the metallic lithium and causes a pretty horrid reaction when it just keeps getting hotter and hotter until flame, fire, explosion…

You might think a small phone would not be much of a hazard but there are a lot of very flammable things in your airplane cabin. And there are a lot of things with lithium ion batteries in them that people bring onboard.

Then there are airplane batteries themselves. Boeing had an issue early on with their 787 Lithium Ion batteries leading to an All Nippon Airways 787 having a pretty serious incident with one before the problem was resolved.

The biggest risk though comes from those in the cargo bay. Particularly the ones that you don’t know are there, should not be there, and which you cannot monitor. A UPS 747 crashed in Dubai after LI batteries in the cargo hold caught fire. The report suggested the heat and smoke from the fire disabled the crew oxygen system and entirely obscured their view within 3 minutes of the initial warning.

Big flames. Not good.

What can we do about them?

Most airlines will have a procedure written into their manuals, but it is worth a quick recap because there are some important bits to note.

- If it has flames, use Halon. If you are using halon (in the cockpit) make sure at least one of you puts a smoke hood on – the stuff is very bad for you.

- If there are no flames and it is just smoking hot, then cool it down by pouring water or a non-alcoholic liquid on it. If it is a laptop or something fixed in the cockpit then have a little think before you go slugging water on it though, because there are other electrics around which might not like it that much.

- Don’t try to pick it up (without gloves on). Don’t cover it with ice thinking this will help cool it better, because it actually just insulates it more making it hotter. Don’t put it in fire resistant bags for the same reason.

- Once it is safe to move, use fire gloves and put it in a receptacle – things like waste bins are good. Fill with water and store it somewhere safe where you can keep monitoring it.

Getting your crew to be vigilant for phones under seats (and passengers not moving said seat until phone is retrieved) is a good plan too.

The Cargo Concern

Lithium Ion batteries in the cargo hold are a different matter. If you have Dangerous Goods approval then you will have manuals and info on this. If you don’t have DG approval then any mention of Lithium Ion batteries on a NOTOC should be concerning you.

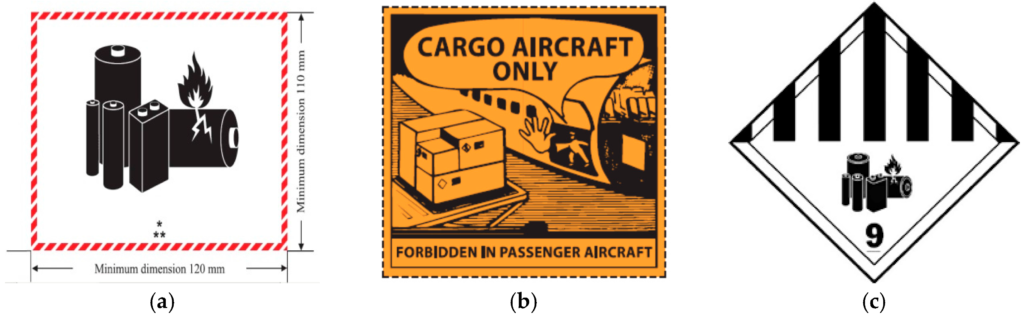

Lithium Ion batteries are a Class 9 Dangerous Good. The ones to look out for are the UN3480 and UN3090 numbers:

- UN 3090, Lithium metal batteries (shipped by themselves). These are are not rechargeable and are designed to be chucked out after their initial use. They are actually Lithium Metal batteries. These are prohibited for carriage on passenger aircraft.

- UN 3480, Lithium ion batteries (shipped by themselves). These are the rechargeable ones found in your phones and things.

- UN 3091, Lithium metal batteries contained in equipment or packed with equipment

- UN 3481, Lithium ion batteries contained in equipment or packed with equipment

Lithium Ion batters are allowed to be carried on cargo aircraft so long as they have been handled properly. The proper handling, packing, labelling and loading (what they need to be separated from) is all covered by IATA in their massive DG Manual. You can get that here, and find some handy online while you’re at it.

Again, if your operator doesn’t have DG Approval then this is just for info. If you’re wondering whether they do have approval then they don’t – crew have to undergo a yearly Dangerous Goods refresher course and you would remember this (because it is generally quite boring).

The DG Labels you’ll want to see on any Lithium Ion filled boxes

So, the simplest thing is to not carry them…

That would be great, but unfortunately it is not that simple. Lithium Ion batteries are in everything nowadays. They come in all shapes and sizes. So the first step is ensuring your passengers know what they are in, and are aware that they shouldn’t be putting these in their checked baggage.

Here is a handy info brochure to give to passengers.

This is a general ‘heads up’ list of some of the things an LI battery might be lurking within:

- First up, those luggage bags which have them installed in them – if the battery can’t be removed and is more than 0.3g or 2.7Wh it probably shouldn’t be carried. If the battery is under those limits, or if it is removable then it can come onboard but only in the cabin, not in checked baggage.

- Any lithium ion battery that is under 2g or 100Wh can generally be brought into the cabin. There is often a limit here (20 per person) but this varies with different operators.

- Mobility aids – electric wheelchairs – often cause problems because folk don’t always know what their battery details are, and it is the airport staff who have to deal with this. The battery on these has to be in an enclosed container to prevent short circuits, and it must be attached as per the manufacturer instructions, or removed if it can be. If it is removed then it must not exceed 300 Wh or 160Wh if there are two of them on the device.

- Hidden batteries – A lot of devices contain batteries. eBikes. Drones. Things that passengers don’t always think about.

The Captain probably needs to know about the location of these, so if you see stuff being loaded on and haven’t been informed about it, ask.

Finally, rogue shippers. Because of the restrictions, people are sneaking them onboard hidden in incorrect packaging, and without declaring them. They key to stopping this is going to lie with the airlines, operators and ground staff who need to be vigilant. The crew cannot do much more than mitigate the situation if some are onboard, and do cause issues.

Here is the full note from the US Department of Transport and IATA

What to do if you have an incident

If you have a Dangerous Goods Incident, you need to report it, and usually quite quickly. The FAA info page is here to help.

Lithium Ion battery fires are extremely hot and burn incredibly fast. If you think you have LI onboard that might be compromised, get that airplane on the ground as quickly as possible, and get your passengers off.

They burn fast and hot

Want to read some more?