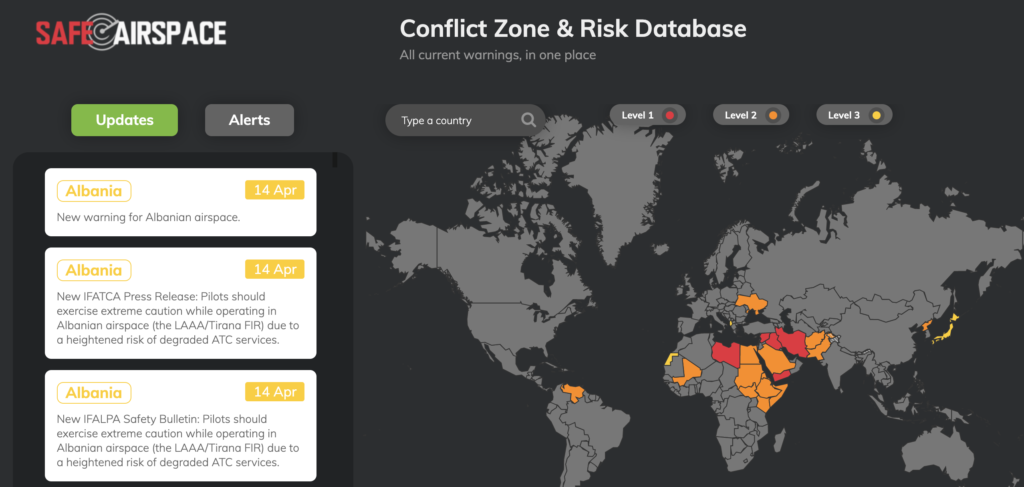

If you’re overflying the Tirana FIR tonight, the Air Traffic Controller in whose hands the safety of your flight rests will be one of these three: a Turkish controller, who has just been drafted in and who has never seen the airspace before; or an Albanian controller who has been forced to work under huge duress, while colleagues remain in prison.

And if you think there will be a NOTAM to tell you about any of this, you’re mistaken. Albania does not want you to know.

There are a plethora of troubling issues in the ongoing Albanian ATC dispute. Arresting workers for organizing industrial action is draconian and aggressive, and an approach discarded by nations that have moved beyond totalitarian regimes of the past. But the issue that presents the greatest risk to aircraft operations is the farm-out of ATC service: a practice whereby the ATC authority recruits foreign, untrained controllers in an attempt to break a strike.

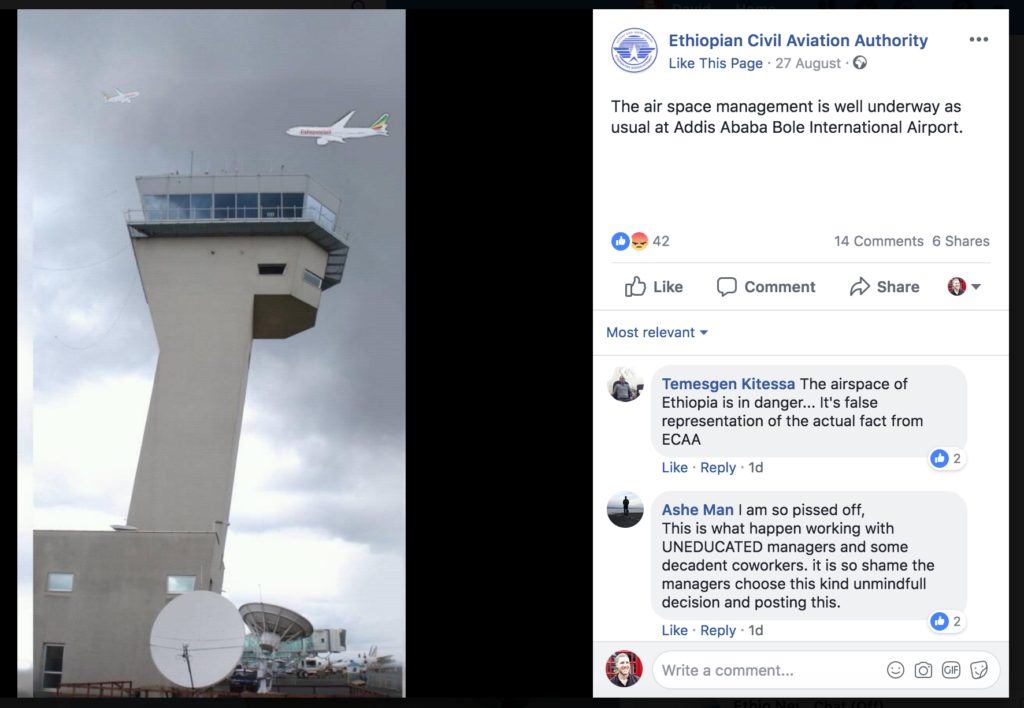

The same scenario occurred in the Ethiopian ATC strike of 2018. The Ethiopia CAA recruited stop-gap controllers from Kenya, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Malawi, and other countries, and at the same time, launched a PR campaign declaring that “everything is operating normally”, including this bizarre attempt at Photoshopping a duo of Ethiopian Airlines aircraft onto an image of Addis Tower.

In the Ethiopian case, the cover-up belied the fact that the Air Traffic Control service was in tatters – many ATCO’s were in prison, many were fired, and the idea that a busload of controllers from Sudan could somewhow safely replace the local controllers was tantamount to attempted manslaughter on the part of the Civil Aviation Authority. Safety was well down the pecking order of motivating factors – commerce, politics, and thinly-veiled vengeance came first.

In Tirana, tonight, the situation is almost identical. Three Albanian controllers are in prison, and those at work in the Tirana ACC are there only because they have been forced onto position by their government. Albcontrol has clearly signalled its intent to draft in Turkish controllers to replace the unhappy domestic ones.

This tactic carries a profound danger that at first glance may not be obvious. If we cross to the other side of the microphone, and look at pilots, we could argue that a 737-rated pilot could fly from Adelaide to Melbourne as easily as they could fly from Dublin to London, and apart from some company procedures and airport familiarisations, that would be largely true. If a group of airline pilots go on strike, management could therefore replace them with a group of other airline pilots with the same type rating – who would earn the monniker of Strikebreaker (or worse). A deeply unpopular move, which happens from time to time, but not one that carries the same risk as attempting to do this with controllers.

Why? Because safe Air Traffic Control is predicated on deeply-learned local familiarity with the airspace, the terrain, the boundaries, and above all, how the traffic flows. This is why it takes six months, on average, for a controller trained in one country to re-qualify in another. For a newly-qualifying controller, that time line is closer to two years.

“OK, where are the mountains again?” is not a question you’d want to know was being asked on the floor of an Approach Control unit. But that is precisely the level of vague airspace acquaintance that a drafted-in controller, even one with thirty years experience in another unit, would have. It is simply not possible to provide a safe ATC service with a weeks training. Even more importantly, the normal time required is based on the training relationship between student and trainer being supportive and co-operative. With the resentment that a Strike breaking controller would face, that cooperation would be entirely absent: the atmosphere will be hostile.

And so, it is a fundamental breach of trust for a sovereign nation to provide ATC service to foreign aircraft under the guise of “operations normal”, when such a catastrophically misguided attempt has been made to solve the dispute.

The relationship between the ATC provider (the state), and the customer (the foreign aircraft), is an extremely unusual one. There is no written contract, no KPI’s, no audit of quality. There is nothing other than a sacrosanct, inherent commitment to safely separate aircraft, crew, and passengers flying over the state. International convention, not corporate agreement, dictates this foundational principle.

And so, international convention must make it clear to countries and ATC authorities alike, that the practice of farming out ATC to untrained, unfamiliar controllers from other countries as a strike-breaking tactic is absolutely unacceptable. Countries must find ways of solving domestic disputes without subjecting uninvolved, unaware pilots and passengers to high-risk scenarios such as this.

Organizations and agencies like CANSO, ICAO, and in this case, EASA, must ensure that this flawed and covertly dangerous pseudo-solution is placed firmly back under the rock it crawled out from.

What happened?

What happened?