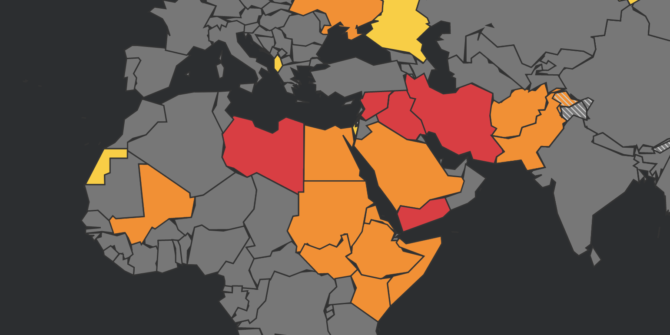

ICAO Doc 10084, if you have not come across it, is a sixty plus page document looking at ‘Risk Assessment for Civil Aircraft Operation Over or Near Conflict Zones’. Important stuff.

But despite manuals and procedures, regulations and recommendations telling us how to watch out for, assess, mitigate and manage the risk of conflict zones, there remains a much bigger and more significant risk to safety because of conflict zones.

So, what is this risk, and more importantly, what can we do about it in the aviation community?

Information

The huge hindrance to maintaining safety does not lie just with the SAMs themselves. It lies with information – the quality, quantity, reliability and promulgation of it. The result is that risk assessments are fundamentally flawed, understanding is limited and critical information does not reach those who need it.

So, there are four big points that need considering when we look at conflict zones and their impact on airspace safety:

- The Bigger Question – A risk assessment is much more than just asking “Is there a weapon down there?”

- Rules alone do not change the behavior of states – Information from states is critical, but it is often not shared, or not shared very well.

- Are we actively seeking information, or simply waiting for it to come our way? – The safety process does not stop at the state level, it continues (should continue) dynamically with operators and with the pilots, so understanding the situation is important.

- How can we do better? – Individuals and the industry have a responsibility to ensure information and strategies are shared.

1. The Bigger Question

The bigger question is to do with how risk is assessed, and it is a complex process even when information is available.

ICAO Doc 10084 lays out the risk assessment process. It’s an interesting read and worth taking a few minutes to think about because understanding the background to conflicts and what the key factors at play are is the only way for safety strategies and risk assessments to continue, and continue they should – it does not stop when a Notam is released.

The process is dynamic and needs to continue with the operator and the pilots too.

What are the key factors in a risk assessment?

First up, what are we actually talking about here? Long-range Surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) can reach aircraft cruising in excess of 25,000ft (7600m). They are often linked with radar sensor systems to help identify targets, and are mobile and easily and quickly relocated.

So we need an assessment of what danger these pose to airlines and airplanes, and this means we need to know who has them (the capability) and also their intent (who or what do they plan to target).

But it is not that simple. Where there is intent, there is not always capability; and as importantly, where there is capability there is not always intent. The Iranian shoot down is a clear example of this. So we also need to consider the unintentional risks as well.

The questions asked look something like this:

- Is there use of military aircraft in combat roles or for hostile reconnaissance (including unmanned aircraft)?

- Are aircraft used to transport troops into the area and do these routes coincide with civil air corridors, or lie close and so pose a risk of misidentification between civil and military aircraft operating in the area?

- What are the politics relating to the region?

- What are the training levels of SAM operators and what is the military deployment of SAMs? How reliable and credible is the information shared by the state regarding this?

- Is there a lack of effective air traffic management over the relevant airspace? Is the state fully in control of their own territory and do they fulfil all their ATC, coordination and promulgation (of information) obligations?

- Do civil aircraft route pass over or close to locations or assets of high strategic importance or which may be considered vulnerable to aerial attack in a conflict situation?

But, the risk continues beyond this initial assessment because we also have to identify any ongoing consequences of an event. If a major airport is targeted, the impact is not only with the initial damage – if that initial damage is to the ATC systems required to maintain control and separation of aircraft then now we have reduced safety in the airspace and a much larger level of disruption.

So, we must think about the overall severity, and with that the tolerability of an infrastructure or operation. We are asking both ‘What can it hurt?’ and ‘How much it will hurt?’

This assessment, according to the ICAO document, is thrown into a matrix and churns out a ‘Risk Level’ which leads to the actions taken.

Sounds simple, but there is one key point here –

This info is not easy to come by. It is rarely reliable, and there is a qualitative narrative that makes it very subjective. The information has to be promulgated from states.

Which leads us to Point Number 2.

2. Rules do not change the behavior of a state….

States are responsible for sharing info on hazards, on what mitigation strategies they have in place, and the assessed impact of the strategies they adopt.

This often does not happen, or it does not happen well. Look at Ethiopia/Tigray region situation – misleading Notams and no guidance from the Ethiopian authorities led to Opsgroup issuing our own warning regarding the situation.

Further to that, ICAO only mandated the reporting of hazards in notices to pilots since 2020, and some states are still failing to do so.

3. People are not seeking information, they are waiting for it to come their way

This is why SafeAirspace was created.

Information is not being shared well and risk assessments are fundamentally flawed because the information on key factors is simply not available or reliable most of the time.

What’s more, people are rarely questioning whether the information they received was reliable, accurate or complete. Few proper risk assessments are taking place because those responsible are waiting for the information to come to them, and without a proper risk assessment, mitigation strategies are not sufficient, and are not being passed on to those who need them – the pilots.

What is the Operator’s continued role in the process?

Every operator is responsible for continuing the risk assessment. It is not enough to simply direct crew to a Notam. Ensuring crew have a full briefing on the threat and any mitigation strategies is important.

- Emergency and abnormal procedures should be considered in advance. Take Mogadishu airspace where only flights on specific airways over the water are allowed. What is the strategy here in case of an engine failure or depressurization? If you operate over this region, you should have access to this information.

- Operators are also responsible reviewing fuel requirements – ensuring additional fuel is provided for potential diversions around conflict zones.

- If aircraft will be operating into conflict zones, then a review of MEL items which can be deferred is a good call – can the aircraft get out again without requiring maintenance or fueling?

What is the pilot’s continued responsibility in the process?

The information and strategies we see at the operations end are things like these:

- Coordination between military authorities, security and ATS units

- Briefings of personnel

- Identification of civil aircraft by military units

- Issuance of warnings and navigation advice

- Air Traffic Restrictions

- Closure of Airspace

But this does not mean the full risk has been removed. Understanding this, understanding how the situation got to this point, and understanding the risk assessment and safety management that has taken place is vital because the process now continues with you, the pilot, and this a fundamental step in continuing to manage safety.

- The Crew, and the Commander of the aircraft are responsible for the safety of the aircraft and the passengers. Of course, we all know that, but if you are given a Notam saying “this airspace ain’t great, maybe avoid it” and then you fly through it, where does the responsibility of your operator end and yours begin?

- Reading notams, the AIPs, AICs, and being aware of the threats of the airspace you might be asked to operate into is vital. More than that, ensure you are aware of any mitigation strategies required.

- Pre-prepare for diversions and know where you can safely go. Some diversions might take you through prohibited airspace so if you are operating in the vicinity of some, have a route ready in box two so you can easily avoid airspace when you need to.

- Be aware of security threats and hazards on the ground, in advance.

- Consider the serviceability of aircraft equipment before you go – critical equipment would be communication systems, and those required to ensure military units can identify them as civilian;

- Have an awareness of the potential political implications if diverting into some regions with certain nationalities onboard. If you divert there, what will happen to your passengers and crew, and why?

- Report things. Keep the information loop going.

4. How can we do better?

Aeronautical info from states and authorities is your first point of call. AICs, AIPs and Notams are going to contain info on advisories, restrictions and recommendations.

If you are an FAA operator, then the FAA put out KICZ notams and this page has all the current ones for airspace.

Networks and organizations such as us here at OPSGROUP try to share relevant and up-to-date information on airspace, conflicts and the risks that are out there.

Open sources like social media and news sites are also good – but be careful, these may come from unconfirmed or unreliable sources. We recommend checking info with other sources too, like handling agents in the area.

Finally, talk to other pilots and operators, and be sure to report information you have from operating in or through airspace.