We’ve mentioned space before because the goings on up there do impact the goings on down here. From space debris falling down, to TFRs around launch zones, to the impact of radiation on flight crew…

This post though is here to help you with Space Weather, or rather, how to monitor it and plan for it in your flight plans.

Space weather and what it does.

What we are talking about are things like geomagnetic storms and solar flares. The stuff that causes pretty Northern Lights shows, but which also causes less pretty impacts on our HF comms and our satellite navigation systems.

In general, the effects of space weather on earthbound stuff is limited to the higher latitudes and particularly the polar routes. For a whole load of information on this have our read of this post we put out a while back. For more info on radiation risk, check this one out.

A possibly not real photo of a solar flare

Flight planning.

This post is a simple ‘where to look for info’ post so you can include (if you don’t already) some of this info into your planning process, and into the information you provide your pilots.

First up, Alerts.

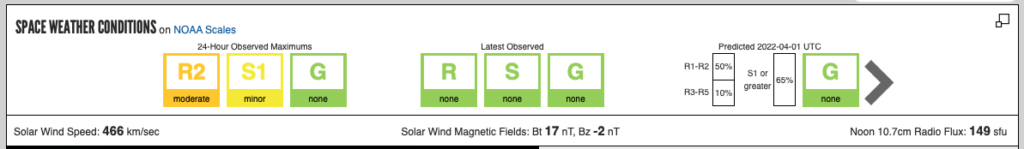

We check the NOAA site daily (the Space Weather Prediction Center part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). When we see little yellow or little orange bits at the top we pop out an alert to let you know the sun might be sending something our way.

Orange more serious, yellow a bit serious, green is all good.

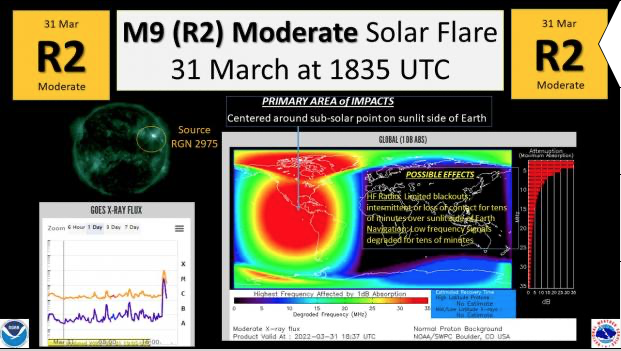

When its something more serious they tend to write up a proper little alert themselves on this.

This is just a forecast though. The R, S and G scales provide a prediction on the level of HF Radio Blackout likelihood (R), Solar radiation probability (S) and Geomagnetic storm impact (G) which would also impact your satellite navigation systems.

Sciencey info on the solar flare

If you see an alert you might want to go check an official aviation source.

Official aviation sources.

Not that we’re saying NOAA isn’t official, but it does just provide a sort of heads up. For your flight planning you are probably going to want some more specific information to put into your flight plan – an actual advisory (rather than our little alerts).

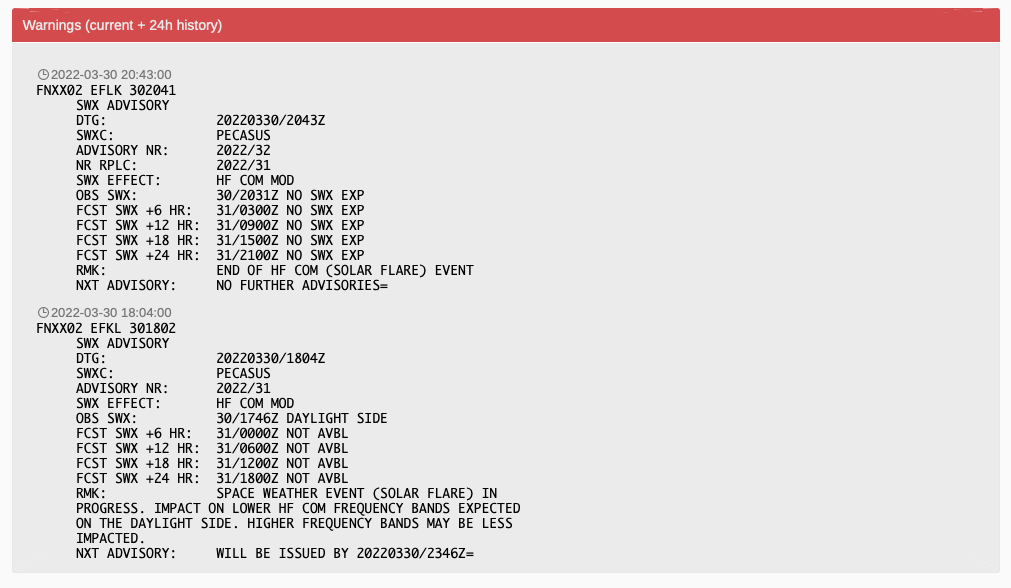

One place to look is somewhere the Finnish Met Institute who put out aviation advisories on space weather. These advisories look something like this –

A forecast and advisory for space weather

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology publish similar ones and even have a nice little map you can look at to see the regional risk of space weather nastiness.

If you are USA based then your go to centre is the Space Weather Prediction Center (under NOAA) and you can find official advisories on there.

What to do next.

There are various things to think about:

- If you are regularly fly at high latitudes then you need to be monitoring their cumulative radiation exposure levels

- If the radiation levels on a particular day are over a certain amount you might want to think about a re-route at a lower latitude (it is rare they are significant)

- If the HF blackout probability is much more than minor (10 minutes max) or the geomagnetic storm levels are likely to cause significant satellite navigation issues then the same applies – you might want to consider re-routes

- For any probability, alerting the flight crew to potential HF blackouts and ensuring they know the procedures for loss of HF comms if routing over HF comm dependant areas is probably a good idea

- Include the forecast in the flights plans just as you would non-space weather forecasts.

We hope that helps, but if you want more…

ICAO put out a fairly handy presentation on this a while ago which you can find here, and they published another on Space Weather Center provisions which you can read here.

The full ICAO SARPS on Space Weather are in the’ ICAO Annex 3 – Meteorological Service for International Air Navigation and ICAO Doc 10100 – Manual on Space Weather Information in Support of International Air Navigation.’

There is also a draft of their original Manual on Space Weather available here (if you want the current published version you’ll have to pay for it).

The ECA (European Cockpit Association) published this which is filled with useful advice.

You might also want to take a read of this and sign up to your local Space Weather center to receive the SWX advisories if you haven’t already.