We last wrote about this back in 2017, after the en-route wake of an A380 flipped a Challenger 604 upside down over the Arabian Sea. But as the skies start to grow busier again it’s worth having a think about how to avoid wake turbulence or deal with it when you come across it.

If you are going to run into wake turbulence, there is a good chance it will happen near the ground. Not the ideal place to suddenly find yourself banking sharply without warning.

The levels of traffic operating in close proximity (and in configurations specifically designed to produce lots of lift which is what basically leads to wake) can make the approach, departure, takeoff or landing a gauntlet of swirling vortices of doom. Added to that, aircraft are generally operating at low speed with lower controllability margins.

A study in Australia looked at the vortices of an A380 and in 35 knot winds, at 2,400ft, it took 72 seconds for the vortices to cover 1300m. They move, and they take a while to dissipate. This study took place after a Saab 340B temporarily lost control, dropping 300-400ft in altitude and rolling 52 degrees left and 21 degrees right.

An ILS calibration aircraft crashed in OMDB/Dubai after breaching minimum separation distances from commercial traffic. Hitting wake is not fun and can lead to catastrophic consequences.

Thankfully, wake turbulence is taken seriously. In fact, in 2016, wake turbulence categories were rethought.

They used to just be based off MTOWs:

- Super (the A380 held this spot)

- Heavy (anything with a MTOW more than or equal to 136 tons)

- Medium (7 tons to 136 tons)

- Light (anything under 7 tons)

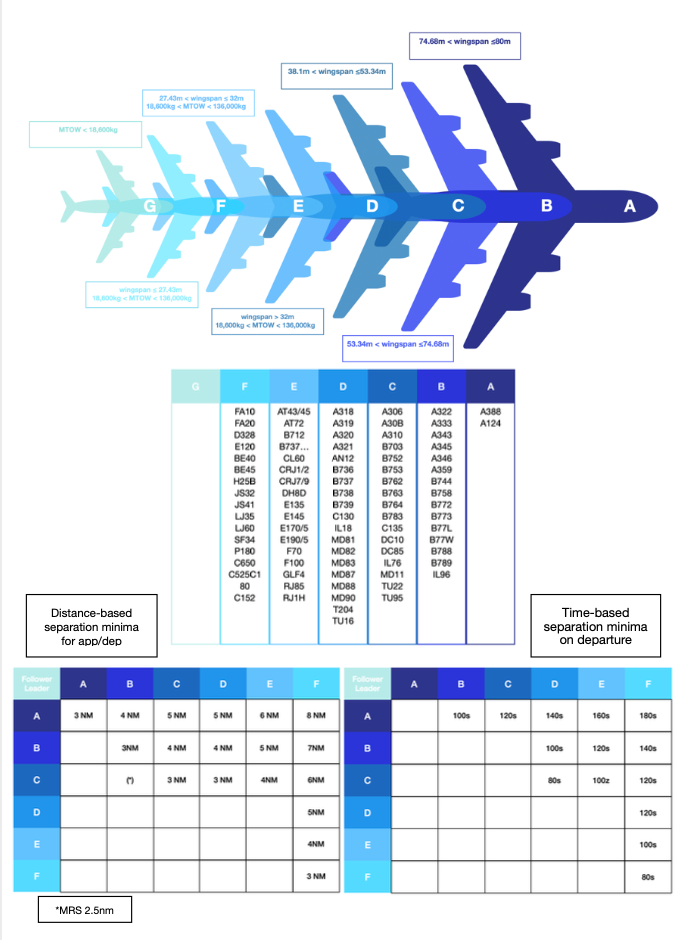

Nowadays, the categories are a little more complex and consider both weight and wingspan, because wing design is a big contributor to what sort of vortices roll off the tips. Now we have 7 categories: G-A. Ultimately, the important thing to remember is the distance you need from each depending on what you are in.

Here’s one we made earlier

Get woke about wake.

So, we have our 7 categories, and we have our distance based separation (which ICAO allows to go as low as 2.5NM).

Something to remember – these have been designed to allow maximum runway capacity and operational efficiency. You won’t be ATC’s favorite pilot if you ask for more separation (you might even lose your spot in the sequence) but safety is ultimately up to you.

If you need more space, say something.

There are a few other things you can do to help avoid wake in the airport area:

- Consider requesting a SLOP on arrival – yes, this is possible. Except where they have super strict NABT routes.

- Consider asking for an extended holding pattern, or opposite direction hold – just check where that might fly you (if you’re close to the border with another airspace you might run into another sort of trouble).

- Try and remain above the flightpath of the preceding aircraft, and avoid long level sections by flying a CDA.

- Watch those speed margins – if you think you might meet some wake, think about taking some flap a little earlier so you have more margin.

- If you are a ‘heavy’ or a ‘super’ then ATC might not want you to fly a CDA, especially in high density airspace. JFK are one such spot.

- Look at what the wind is doing – if it’s light or variable then those vortexes are going to sit there, waiting for you to fly into them…

Is there any technology to help?

There is indeed. In fact, there are several interesting projects and technologies being tested to help with wake.

Vortex modelling is playing a major part in the EU’s Single European Sky ATM Research and has led to some rather clever folk in Germany discovering that if you build a “plate line” (basically a wall of large wooden boards) this effectively cancels out most of the wake. This is being tested at EDDF/Frankfurt and EDDM/Munich airport using smoke and lasers.

Not so clear air turbulence

Turbulence can really CAT-ch you out.

Going back to the 2017 Airbus 380 vs Challenger 604 battle – the Challenger came off a lot worse.

The big takeaway from this: the risk of wake in cruise is a pretty big one as well. So what can you do about it?

- SLOP – It is one of the things it was designed for.

But use a bit of common sense here – if the wind is from the left (and slopping to the left is not available), then flying to the right of track just means when you get to abeam where the aircraft in front was, their wake has probably been blown right of track as well. Maybe ask them to SLOP!

Don’t play Chicken, be a chicken and SLOP

Of course, severe turbulence isn’t only caused by wake. Weather, mountains, atmospheric stuff are all to blame as well.

There are technologies out there to help with this as well. Lidar is just such a thing. The Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency and Boeing have discovered that if you stick one of these onto the side of an airplane then it can detect aerosols on the air. These are tiny particles, such smaller than water droplets so a conventional radar won’t detect them. The Lidar system does though, and can provide up to around 70 seconds warning (about 10 miles).

This might not always be enough to avoid, but it’s enough to switch the seatbelt sign on and warn everyone down the back.

So, sometimes there are warning signs, but sometimes there aren’t. We aren’t going to bore you with a science lesson on Clear Air Turbulence or how to check your shear rates. What we do think is worth talking about is what ICAO, EASA, the FAA et al. have say about what to do when you have inadvertently come across something that has really upset your airplane.

UPRT

Upset Prevention and Recovery Training. This is a big (and very good) thing. Since the AF447 accident it has become mandatory for crew to be trained in UPRT.

But what actually is it?

Well, it is one answer which is hoping to solve the issue of LOC-I incidents amongst other things. Loss of Control in flight is the biggest cause of fatal accidents over the last two decades (on commercial jet aircraft), having led to 33% of fatal accidents.

It is designed to solve the “startle” factor by giving a clear, defined method of what to do if you don’t really know what is going on. Basically, when you experience an “unusual attitude” (with the airplane, not with a strange co-pilot).

Not what you want be seeing

An unusual attitude is anything outside your aircraft’s normal limits. For a large transport category aircraft we are probably talking nose up more than 25 degrees of pitch, or down more than 10, a bank angle greater than 45 degrees or any flight within these parameters but with airspeeds “inappropriate for the conditions”.

What has changed here from the old-school stall recovery type training?

Well, the big change is what we are really learning during the training. Upsets are not “some aerodynamic phenomenon lurking in the atmosphere to grab pilots following well structured procedures” – they happen when things have gone very, very wrong and procedures have flown out the window.

So, UPRT is about training to deal with the startle and the confusion – giving a method to right the airplane when that startle and confusion is likely preventing you from doing so. It is also about learning how to recognize a potential threat that might lead to an upset, and it is about better monitoring to prevent the startle.

Tell me how to do it.

Probably more for a trained instructor, but the general gist is this:

- Push

- Roll

- Power

- Stabilise

(Sometimes Roll and Power might want to go in the opposite order.)

Pushing does not mean ramming the stick forward. It means unloading the wings. And once they are unloaded you want to stop the push, but that doesn’t mean yanking the nose back up into a negative-G maneuver. You are going to have to trade some height for speed (and safety) here. When the aircraft is back under control, that means gently returning it to the horizon.

Roll is similar – it is all about giving the wings the best chance of performing, and that means getting them level and not barrel-rolling around the sky. But… if your nose is mega high, and you have power on, then pushing forward is going to be tough to do. So adding some roll can also help us out here, getting the nose to drop, and giving us control of, well, the controls.

UPRT is about monitoring, recognizing and handling.

Fancy some further reading?

- Here is a link to the FAA Advisory telling you all about their recommendations for UPRT.

- Here is a big old document on Wake RECAT, by EASA.