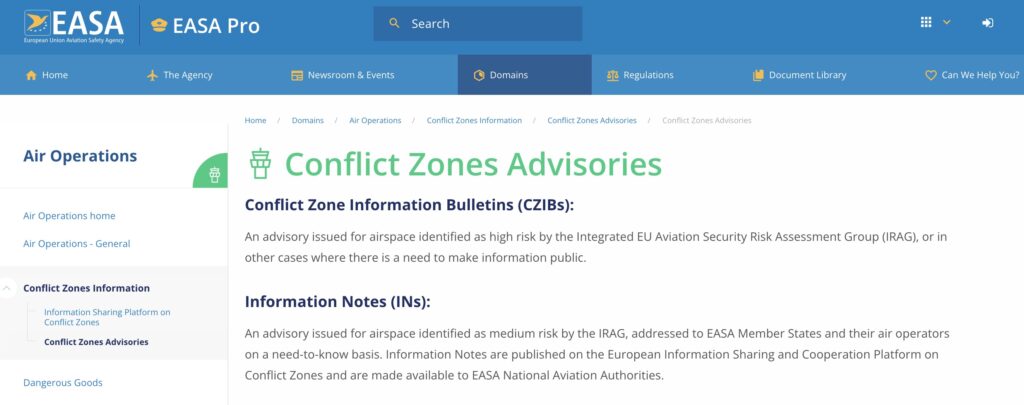

On 22 Feb 2026, EASA brings the Part-IS Information Security regulation into force.

This is not a new avionics requirement, and not a connectivity upgrade mandate. It’s a management system rule. EASA wants certain aviation organisations to show they understand and manage cyber and data risks that could affect aviation safety.

That includes things like aircraft networks, satcom and cabin connectivity, data flows, access to systems, and how cyber incidents are handled. EASA’s view is simple: if a digital failure or attack could impact safety, it needs to be treated like any other operational risk.

The most important point up front: Part-IS only applies to organisations EASA regulates. Flying into Europe alone does not put you in scope.

What affected operators actually have to do

If you’re in scope, EASA expects a working information security management system that fits the size and complexity of your operation. Not theory, and not a one-off document exercise.

In practical terms, inspectors will expect to see that:

- You’ve assigned responsibility: Information security sits at management level. It’s owned, not outsourced to “IT”.

- You know what matters operationally: You’ve identified systems and data that would hurt safety or operations if compromised. That usually includes connectivity, EFB links, maintenance and planning systems, and interfaces with third parties.

- You actively manage risk: There’s a repeatable process to identify, assess, mitigate, and review cyber and data risks. This updates when things change – new aircraft, new satcom, new apps, new vendors.

- Basic controls are in place: Access control, configuration management, patching, backups, logging, and secure remote access. Nothing exotic, but it must exist and be used.

- You can deal with incidents: You can detect issues, respond, recover, and learn. If an information security event could affect safety, EASA expects it to be managed properly.

- You manage suppliers: Part-IS pushes hard on supply chain risk. Operators are expected to understand and manage information security risks across connectivity and data providers, not just internally.

Do operators have to submit anything before Feb 22?

Short answer: no. There is no blanket requirement to submit a declaration, form, or compliance statement to EASA by 22 Feb 2026.

Instead, EASA expects that from that date, your Part-IS setup exists and is actually working.

Compliance is checked through normal oversight. That means Part-IS will typically be reviewed at your next audit or inspection, during approval changes or renewals, or earlier if there’s any kind of incident or trigger event.

Bottom line: no paperwork deadline, but also no grace period. From 22 Feb, you need to be audit-ready.

Who is definitely not directly impacted

This is where most of the confusion sits.

Part-IS does not automatically apply to:

- US Part 91 operators.

- US Part 135 operators.

- Privately owned foreign registered aircraft.

- Operators with no EASA approval or certificate.

- EASA Third Country Operator (TCO) authorisation holders.

If you don’t hold an EASA AOC, EASA has no legal way to enforce Part-IS on you.

So the common scenarios we’re hearing about:

- A US owner flying a jet into Europe under Part 91, with no EASA approvals – no direct Part-IS compliance requirement.

- A US charter operator flying into Europe under Part 135 and holding an EASA TCO only – again, no direct Part-IS compliance requirement.

Flying into Europe, or holding a TCO, does not by itself make an operator subject to Part-IS.

Why you might be getting emails from your connectivity provider about this

So why are operators being told “this affects you” and “you must be ready by 22 Feb”?

Because connectivity providers sit inside the compliance chain.

Their EASA-regulated customers will be audited. Auditors will ask how information security is handled end to end, including customer configurations, access rights, data routing, and system interfaces.

Providers likely don’t want two security standards, weak links in customer setups, or any awkward audit questions they can’t answer!

So they might be pushing requirements downstream via contract changes or software upgrades.

For operators outside scope, this can feel like a regulatory mandate. It isn’t. It’s commercial and risk-driven pressure, not a new EASA legal obligation.

Bottom line

Part-IS is real and it matters – for EASA-regulated organisations. For non-EASA operators, the impact is indirect, driven by vendors and contracts, not regulation.

If you don’t hold an EASA approval, Part-IS is not suddenly your problem on Feb 22. But expect more security questions from the companies you connect to.

Give it to me in plain English.

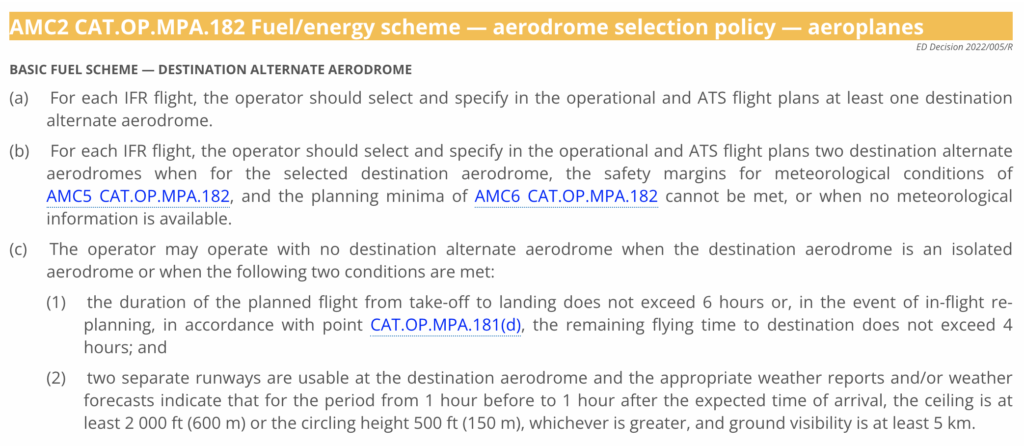

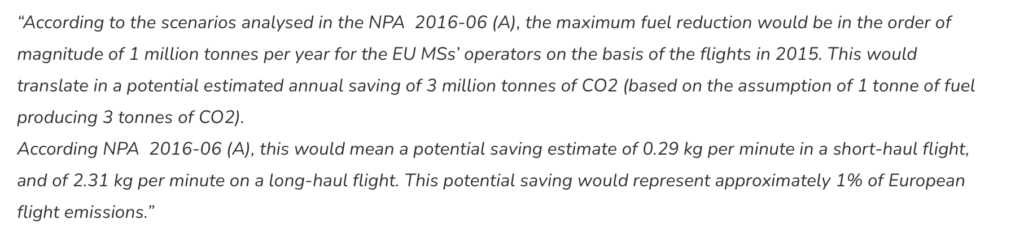

Give it to me in plain English. So let’s look at the schemes.

So let’s look at the schemes.

It’s been a great few days on a sun-soaked Mediterranean island. Your passengers are onboard, you are about to close the door, and then you get told your Calculated Take Off Time (CTOT) is an hour from now! Sound familiar? You’re not alone! ?

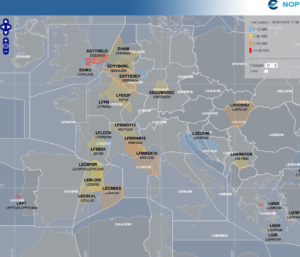

It’s been a great few days on a sun-soaked Mediterranean island. Your passengers are onboard, you are about to close the door, and then you get told your Calculated Take Off Time (CTOT) is an hour from now! Sound familiar? You’re not alone! ? “Data from Eurocontrol shows that in the first half of 2018, Air Traffic Management (ATM) delays more than doubled to 47,000 minutes per day, 133% more than in the same period last year. Most of these delays are caused by staffing and capacity shortages as well as other causes such as weather delays and disruptive events such as strikes. The average delay for flights delayed by air traffic control limitations reached 20 minutes in July, with the longest delay reaching 337 minutes.”

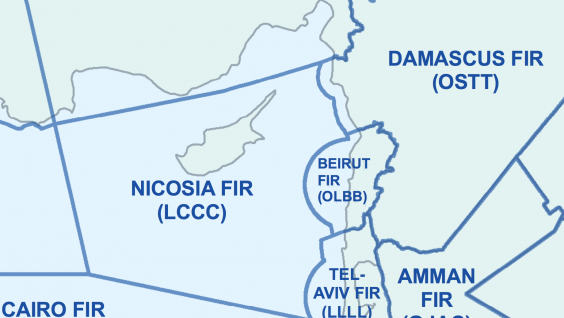

“Data from Eurocontrol shows that in the first half of 2018, Air Traffic Management (ATM) delays more than doubled to 47,000 minutes per day, 133% more than in the same period last year. Most of these delays are caused by staffing and capacity shortages as well as other causes such as weather delays and disruptive events such as strikes. The average delay for flights delayed by air traffic control limitations reached 20 minutes in July, with the longest delay reaching 337 minutes.” EDYY (Maastricht)

EDYY (Maastricht)