2020 was an interesting year for aviation. It was dominated by Covid, which saw traffic numbers fall to the levels of several decades before – which is why a review of the accident statistics is an interesting one to consider.

What sort of accidents are taking place?

The primary accidents seen in 2020 are unsurprisingly similar to those seen over the last decade:

- Runway excursions

- Loss of control in flight

- CFIT

- Abnormal runway contact (hard landings and tail strikes)

- Actually missing the runway (undershoot and overshoots)

- System malfunction or failure

- Fire

We wrote a bit about these in a bit more detail not that long ago. We called it the ‘Seven Deadly Things’ and you can read it here.

What are the 2020 stats?

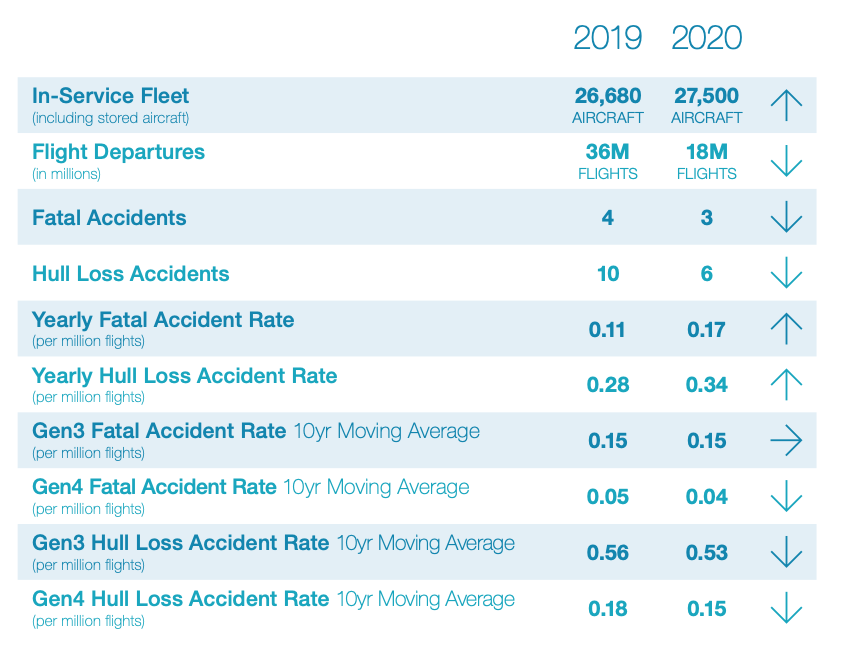

Well, first up, 2020 was roughly the same in terms of capacity as 1998 – a year known for Bill Clinton, the inception of the Euro and the movie ‘Titanic’. Yep, that long ago. So, same traffic levels, but different accident rates – 1998 saw 10 fatal accidents and 24 hull losses compared to “just” 3 and 6 in 2020.

But if we compare the 2020 numbers to 2019 it paints a different picture. Or rather, it is actually a very similar picture. While there there were only roughly 50% the number of flights in 2020 that took place in 2019, there were still 75% the number of fatal accidents.

OK, this isn’t a very telling statistic since we’re talking 3 instead of 4 and neither is huge, but it does mean the fatality rate and hull loss rate went up per million flights in 2020. It was not a significant increase, but it is enough to suggest that yes, not flying regularly can lead to more accidents and incidents.

Not really news there then, but something worth considering.

The Stats for 2019/2020 (Credit: Airbus)

Point number 1 – Lack of flying leads to mistakes

If we take a leap back to 1958 and look at the accident rates through the decades then there has been a steady overall decline, and now we are sitting “comfortably” at under 5 fatal accidents per year, while flights have increased from about 12.5 million (1989 sort of time) to 35.8 million (the peak in 2019).

So, in thirty years the rate per million flights has dropped significantly to around the 0.17 per million flights point, and hull losses to 0.34 per million.

How did it get so low?

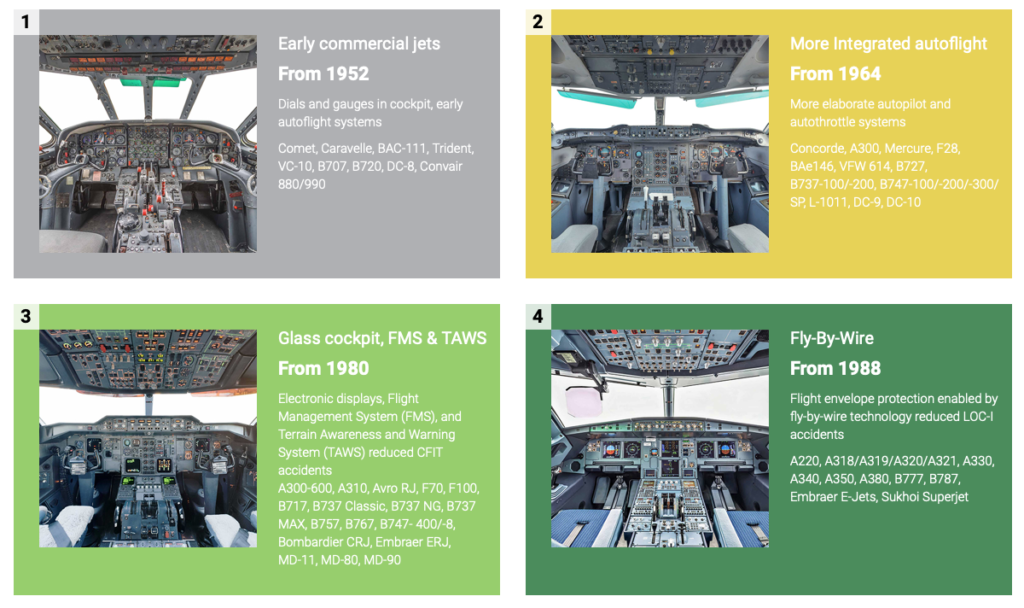

Significant leaps have been made in aircraft design over the years and this has had a huge impact on safety levels. Of course, training, CRM, Human Factors awareness and all of that has played a part too, but the major pat on the back goes to the airplane builders. For every silly mistake a pilot has made, they have generally identified it and then helped prevent it by building us better instruments, more robust systems, or things that catch our mistakes for us.

In fact, if you look at the fatal accident rates per million and then break it down into aircraft generation, it has dropped from 3.0 to 0.1 , and 5.4 to 0.2 for the hull losses. So technology is helping us. A lot.

Those big ones – the CFITs and LOC-I accidents – have reduced by 86% and 89% because of technology upgrades from Generation 1 to Generation 4 aircraft. This is down to the introduction of things like glass cockpits, FMW and TAWS systems.

Evolution of Commercial Jet Aircraft (Credit: Airbus)

How low can it go?

Can we reduce the occurrences to zero? If not, even with all this handy automation, then why not?

Well, these statistics offer us an answer there as well.

They are taken from across civil aviation, revenue flights on western built commercial jet aircraft that carry over 40 passengers, and also big cargo ones. It doesn’t include non-western built aircraft (possibly because the safety records on them ain’t great), and it doesn’t include Business Aviation.

Why not? Well, because the operational environment is very different, and very different in challenging ways.

So, we are looking at the accidents which have involved nice, relatively modern commercial aircraft generally piloted by experienced folk going into places they have gone into many times before. And yet they are still managing to get it wrong.

What’s more, we’ve seen how automation is helping – it has brought us down to a very steady level. So what is going on? We recently published a piece on the ‘Hidden Risks of Automation’, which we think offers some of the answer.

All the gadgets

The ‘Problem of the Person’

Unfortunately, the solution to the Problem of the Person is not a simple one.

‘Human Factors’ might give us some reasons – poor decision making, bad workload management, lack of understanding the systems, but none of these really provide the answer to correcting it. The work now comes down to us.

1. Don’t Become Complacent: We have multiple systems put there to provide another layer of safety but we are seeing pilots rely on them as the only level of safety. These systems are a last line of defence though, not the the only defence.

ROW/ROP should supplement good landing performance assessment and stabilized approach management.

TAWS and GPWS systems give us a hard floor that we must not go below, but our own situational awareness should keep us well away from ever having to hear those calls.

Autopilots, flight protections and warnings should be a final alert, but basic airmanship and handling skills should correct our flightpath long before we reach a level that needs those systems to help.

2. Poor Decision Making and Workload Management: None of our clever automation and systems have the ability to think and question for us. So we need to make sure we are doing this, and we need to make sure we are doing it in the right way. Ask the right questions, gather information and use your resources properly.

Ask “What does this mean?” – Diagnose the problem not based on what has happened, but on what the impact and consequence of that failure is.

Ask “What has changed?” – Review your decisions. Don’t fit new information into the solution you’ve already picked, rather adapt your solution to consider the new information.

Ask “What do you think?” – Open-ended questions that gather input from someone else might catch things you have missed, or misinterpreted.

3. Just Do better

When we have seen automation and systems reduce the number of occurrences down to this point where the vast majority of accidents are down to human error, there really is no better solution than us Just Doing Better.

But this ‘better’ falls on the whole industry.

Sharing information, experiences, supporting development in others and improving training and pilot resilience.

There are multiple projects out there:

- IATA and the Flight Safety Foundation have just released their recommendations for reducing runway excursions (GAPRE).

- ICAO are implementing new Runway Condition Assessment and Reporting standards from the end of this year.

- UPRT training is being developed and improved.

- IATA and ICAO Evidence Based Training development is shifting the training paradigm to train competencies rather than practicing solutions to singular events.

At the end of the day, aviation has grown progressively safer and more efficient over the last few decades, but the trend is flattening out and the same events seem to be occurring, for the same reasons. The ball is now in our court to try and fix the remaining issue – because, as harsh as it sounds, that issue is us.

The last line of defence is us

Fancy reading some more?

- We got a lot of our info from the Airbus Safety Analysis report, and you can check it out here.

- The Global Action Plan for Preventing Runway Excursions is full of recommendations. You can see the report here.

- Here’s one we wrote earlier on Unstabilised Approaches which are one of the most common precursors to runway excursions and abnormal landing events.