In the brave new world of pilot training there is a new paradigm – evidence based training. But evidence of what? Well, of pilot competencies – a set of ‘tools’ for a pilot to quick draw out of their metaphorical tool belt in order to help them solve whatever situation flies their way.

Where does Decision Making fit into this tool belt?

It can be viewed as a sort of Swiss army knife of a competency because it is one which, when wielded well, helps build best outcomes, but when used badly will probably leave you with a few pieces of splintery wood and a nail through you hand.

The (badly metaphored) point trying to be made here is that the Decision Making & Problem Solving ‘competency’ is a big, multi-faceted one, and it turns out that making a decision is often easy, but making a good one is less so…

Decision Making is about using information to find a solution, not forcing it to fit what you already decided

Double E’s give us the ‘O’ factor

A good decision, or an ‘optimal’ one is going to be the one that leads you to the safest, most efficient and effective outcome.

Efficient because you’ve done the ‘best’ thing. Effective because you got there the ‘best’ way.

Reaching this optimal solution is easier said than done though. You, the pilot, want to be as safe as possible, but then you have authorities wanting you to tick every rule and regulation box, and you have your company wanting you to tick every commercial box, and before you know it you can find yourself heaped under a pile of “What Ifs?” and “Why didn’t you’s?”.

All of which can quickly incapacitate any common sense and airmanship. So what can you do about it?

Have you heard the story of the Nimrod?

Everyone knows the Hudson tale, and a great story it is too – a captain (and crew) showing a level of decision-making that saved the lives of all passengers onboard. Well, the story of the Nimrod is similar.

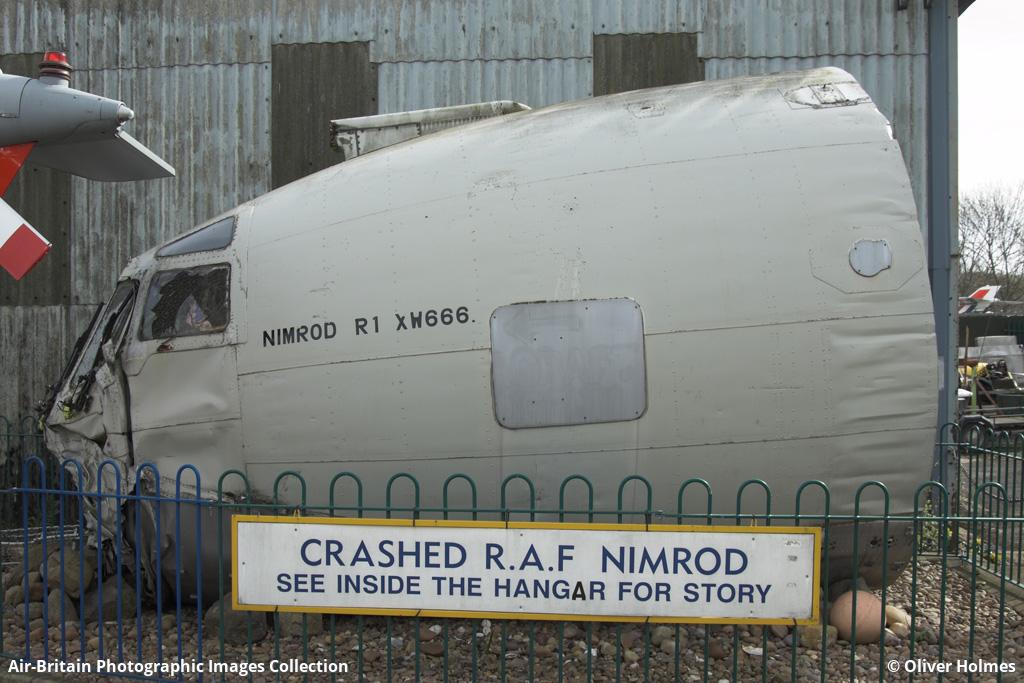

It took place back in 1995, over the coast of Scotland. XW666 was a BAE Nimrod R.1P operated by the RAF, en-route from EGQK/Forres-Kinloss RAF station. They were approximately 35 minutes into the flight when the crew had a No 4 engine fire warning illuminate. During the drill to deal with this the No 3 engine fire warning also illuminated.

The moment that makes this story worth telling was this – at just 4.5nm from EGQS/ RAF Lossiemouth (and its 9,068 feet of runway) the captain discontinued his attempt to put the aircraft onto a tempting piece of tarmac, and instead ditched into the cold water of the Moray Firth.

So why, with just 4.5nm to go between him and a much easier landing, did the captain do this?

A monument to a ‘crash’ worth celebrating

The captain had asked the rear crew member to watch through a window and to inform him if fire became visible through the aircraft structure. When this report was received, the captain ditched. When they dragged what was left of the poor Nimrod out of the water (actually, quite a lot of it was left and all the crew survived), the investigation confirmed that the structural integrity of the wing’s rear spar had deteriorated by over 25% in just 4 minutes.

In the time it would have taken to cover that last 4.5nm the wing would have failed, resulting in an uncontrolled crash.

The big learning point here though is that it wasn’t so much the ‘good decision’ (the “let’s land this thing quick” decision) that was the big save, but actually the captain’s ability to change his decision – to review the situation and say “yup, that ain’t gonna work anymore, let’s do this instead.”

When a good choice turns bad

Doesn’t this satsuma look fresh, fruity and delicious? Most people (who fancy a piece of fruit) would probably happily eat it.

I am hungry, I like fruit, this is a piece of fruit, I shall eat it – Problem diagnosed, options considered, decision made, action assigned… DODARing 101.

Yums

But what about now?

Less yums

Turns out it was made of liver paté.

The (rather odd) point to take away from this is that a decision, based on the information you have, can be great. The best. The optimal. The satsuma of choices. But if the information changes, or if it turns out to be incorrect, then so too might the decision be. So fitting information into what you have already decided does not work. Nor does sticking with a decision and not continuing to gather information.

The golden rule of Decision Making, and the one the Nimrod captain applied so well, is the importance of the review – being able to change a decision when it needs changing.

This can be a tough thing to do. As pilots, we are very goal orientated, but when that goal becomes too focused – the “must land now”, or the “it looked alright 5 minutes ago, I’m sure it still is” attitudes – these can lead to unstabilised approached, overruns, accidents (more on that here).

So, don’t be a Nimrod, be like the captain of one instead!

The pilot at the controls of a Beechcraft B200 Super King Air that crashed shortly after take off had the aircrafts rudder trim in the full left position for take off, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) has found.

The pilot at the controls of a Beechcraft B200 Super King Air that crashed shortly after take off had the aircrafts rudder trim in the full left position for take off, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) has found. Approximately 10 seconds after the aircraft became airborne, and two seconds after the transmission was completed, the aircraft collided with the roof of a building.

Approximately 10 seconds after the aircraft became airborne, and two seconds after the transmission was completed, the aircraft collided with the roof of a building.