**Update: June 2, 07:35z **

South Korea, the Philippines and Japan have all issued new airspace warnings by Notam due to the risk caused by falling debris. Japan’s in particular is worth noting as it also suggests an ‘anti-ballistic missile’ may be launched from several potential locations within the RJJJ/Fukuoka FIR to shoot down the craft if it enters Japanese airspace during launch.

The Notams to be aware of are:

South Korea: RKRR Z0298/23 - ROCKET LAUNCH WILL TAKE PLACE FROM NORTH KOREA. IN THE INTEREST OF AVIATION SAFETY, WI INCHEON FIR ALL ACFT ARE STRONGLY ADVISED TO KEEP LISTENING TO THE FREQUENCY AND FOLLOW THE INSTRUCTION OF ATC. EXPECT FALLING AREAS ARE AS BLW : 1. 360656N 1233307E-352431N 1232247E-352001N 1234837E-360226N 1235911E 2. 340554N 1230159E-332328N 1225153E-331632N 1232940E-335858N 1234004E 3. 145410N 1284006E-111918N 1291050E-112649N 1295408E-150142N 1292403E. 31 MAY 08:38 2023 UNTIL 10 JUN 15:00 2023. CREATED: 31 MAY 08:38 2023

Japan: RJJJ P2445/23 - ALL ACFT INTENDING TO FLY WI FUKUOKA FIR ARE ADVISED TO PAY SPECIAL ATTENTION TO THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION. A ROCKET IS EXPECTED TO BE LAUNCHED FROM NORTH KOREA AND THE ANTIBALLISTIC MISSILES MAY BE LAUNCHED FOR THE DESTRUCTION OF THE ROCKET. 1.ROCKET LAUNCHED FROM NORTH KOREA (1)LAUNCH SITE: NORTH KOREA (2)FALLING AREAS COORDINATES: FIRST STAGE 360656N1233307E 352431N1232247E 352001N1234837E 360226N1235911E SECOND STAGE 340554N1230159E 332328N1225153E 331632N1232940E 335858N1234004E THIRD STAGE 145410N1284006E 111918N1291050E 112649N1295408E 150142N1292403E 2.IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 82-3 OF JAPAN SELF DEFENSE FORCE LAW, THE ANTIBALLISTIC MISSILES ARE DEPLOYED AT POSITIONS BLW, (1)NAHA-SHI : 261219N1273929E (2)MIYAKOJIMA : 244602N1251930E (3)ISHIGAKIJIMA : 241953N1240828E (4)YONAGUNIJIMA : 245838N1225716E. SFC - UNL 30 MAY 15:00 2023 UNTIL 10 JUN 15:00 2023. CREATED: 30 MAY 13:57 2023

Philippines: RPHI B1867/23 - SPECIAL OPS (SATELLITE LAUNCH ACT) WILL TAKE PLACE WI: 145410N 1284006E - 111918N 1291050E - 112649N 1295408E - 150142N 1292403E - 145410N 1284006E. SFC - UNL, 30 MAY 15:00 2023 UNTIL 10 JUN 15:00 2023. CREATED: 30 MAY 02:31 2023

**********

It has been a busy week for the aspiring North Korean space program.

In an unusual turn of events, on May 29 they actually provided prior notice of an impending launch of a (suspected) surveillance satellite into orbit. Then on May 30 it actually lifted off, although unsuccessfully. Alarms were briefly triggered in South Korea and Japan. No sooner had the dust settled than Pyongyang announced their intention to try again – sometime before June 11.

Similar attempts in the past have turned out to be yet more thinly veiled missile tests. Nevertheless, the global community is taking these warnings seriously, and word is being spread by Notam.

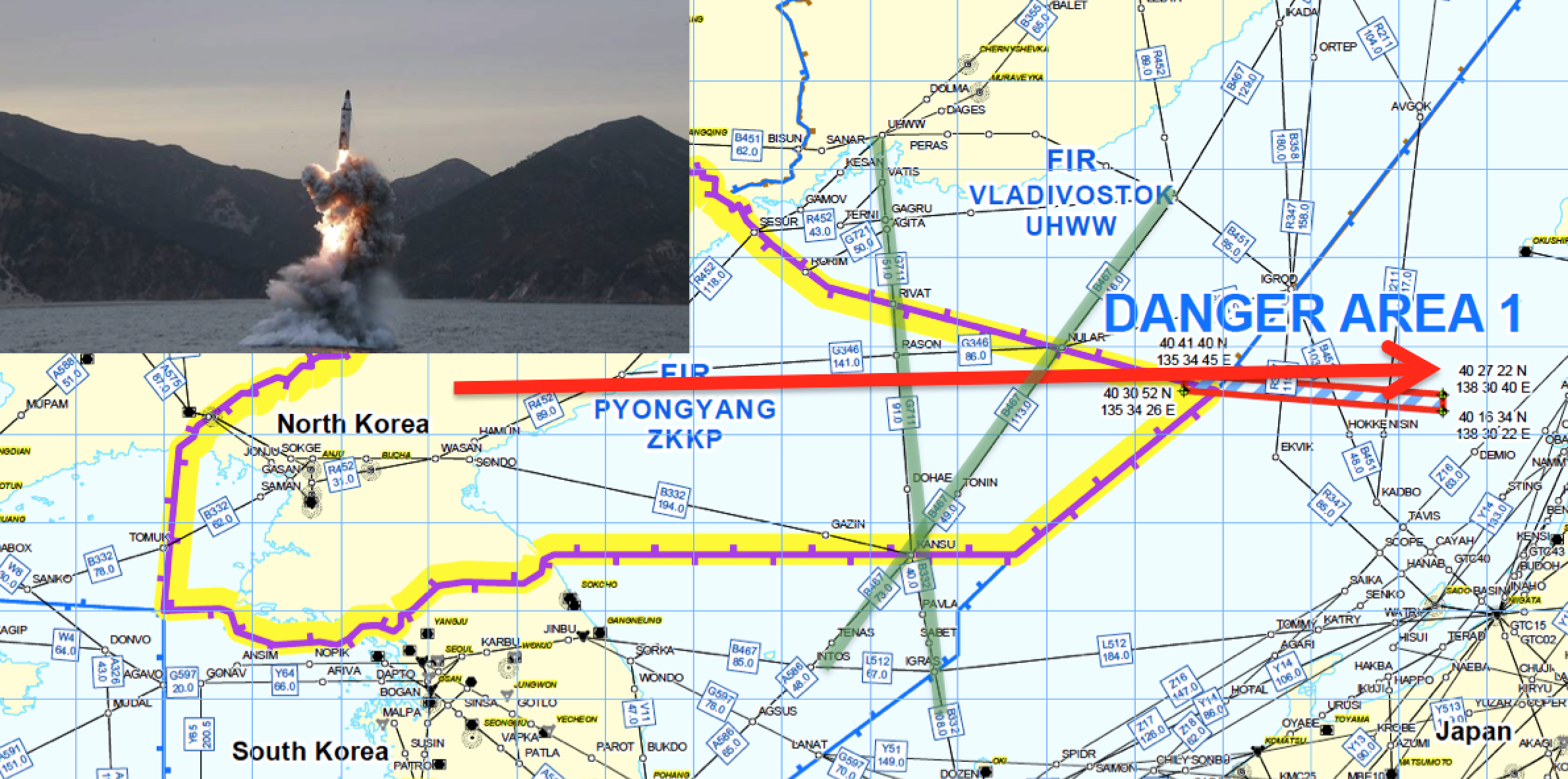

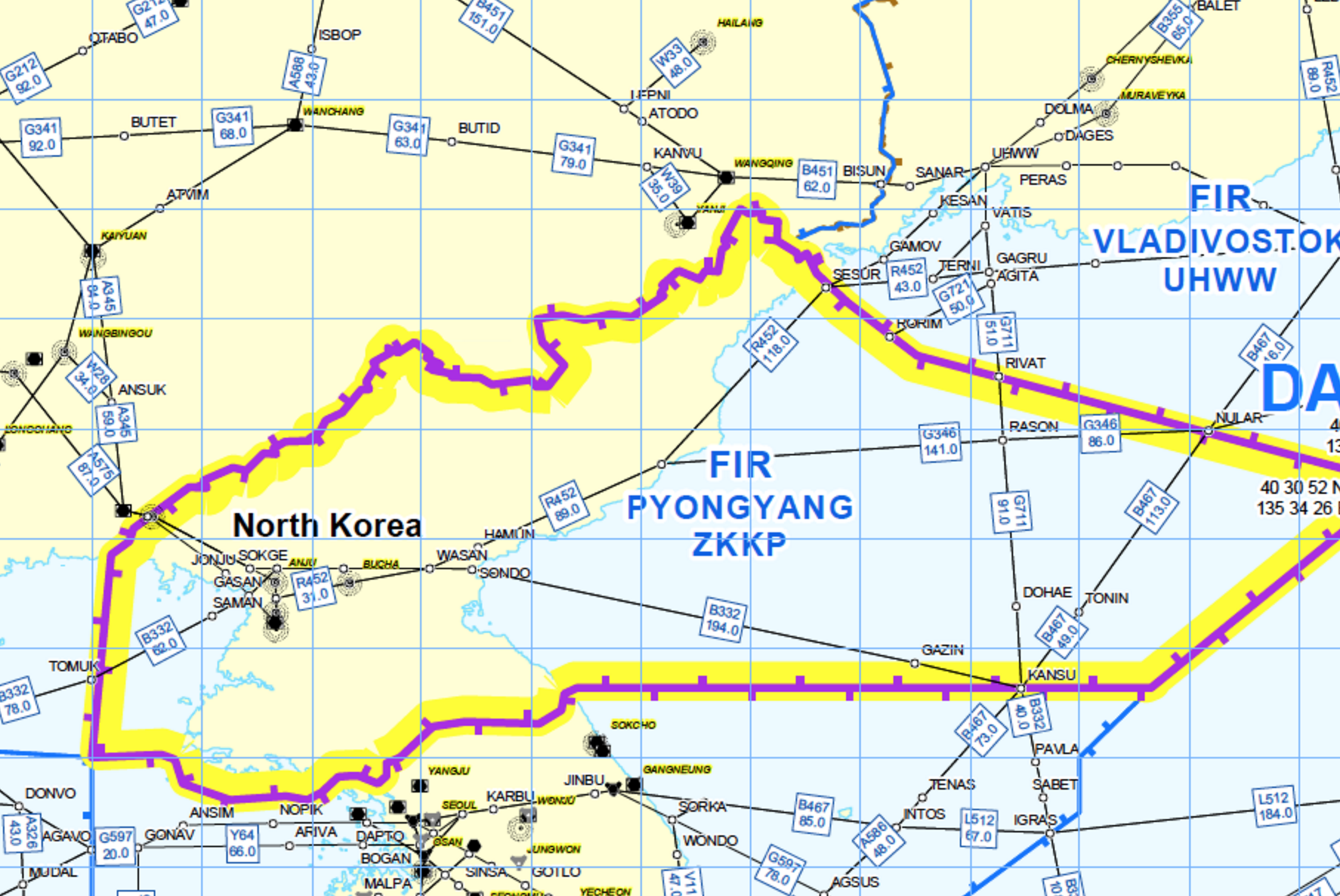

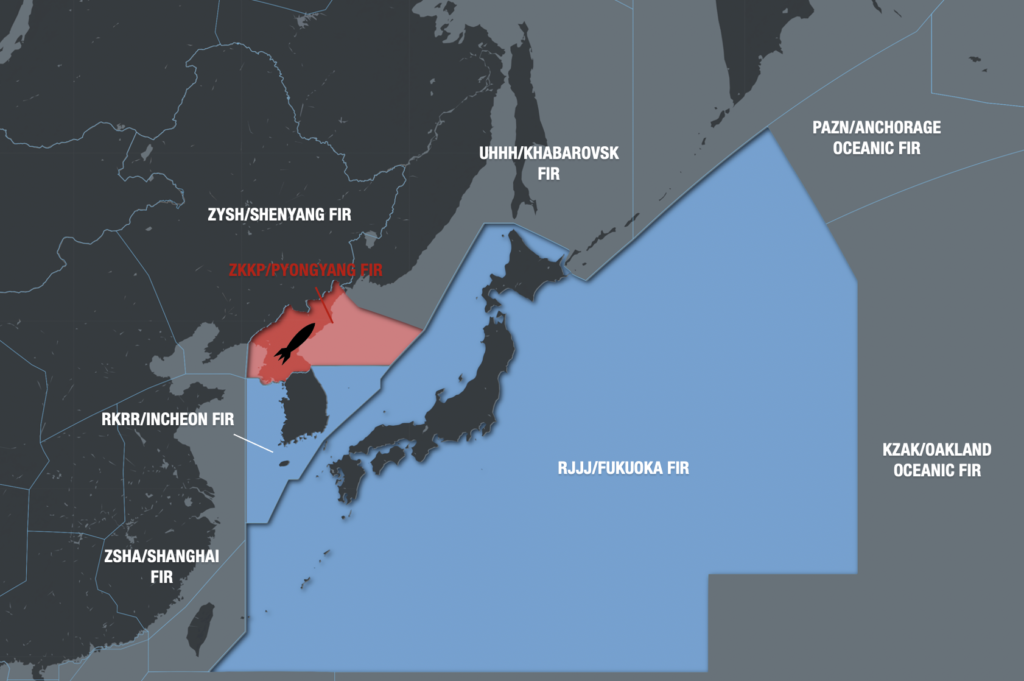

Unlike conventional missile tests which we have frequently reported, an attempt to put something into orbit not only uses UN-sanctioned technology, but creates far broader hazard areas for civil aviation – well beyond the ZKKP/Pyongyang FIR where traditional missile tests lie. Which is why we’re collectively sitting up a little straighter.

Not all of the beans are being spilt though. Only some of them. Which is why this week’s launch window was notably broad – extending for a full ten days. Subsequent launches are likely to be same.

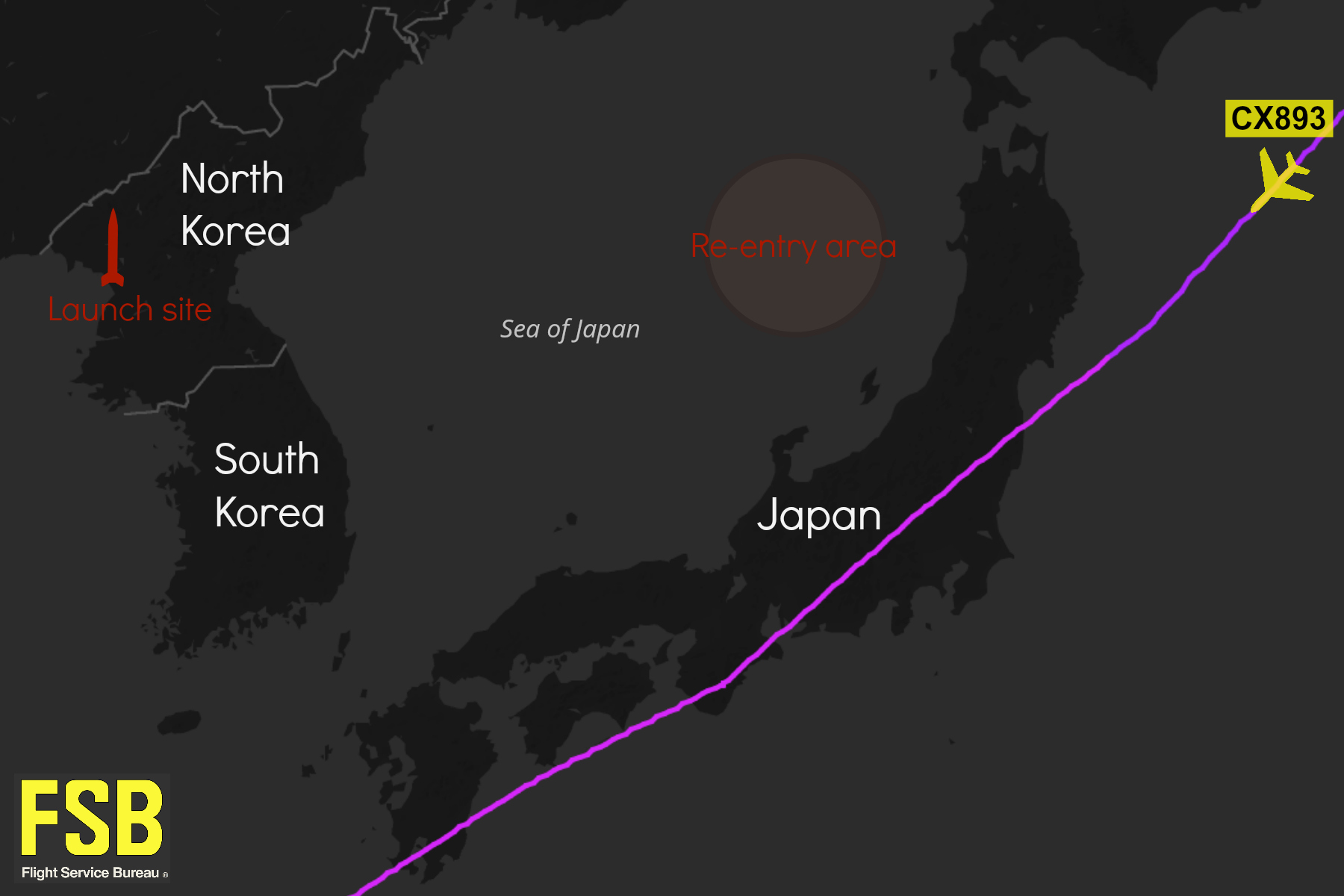

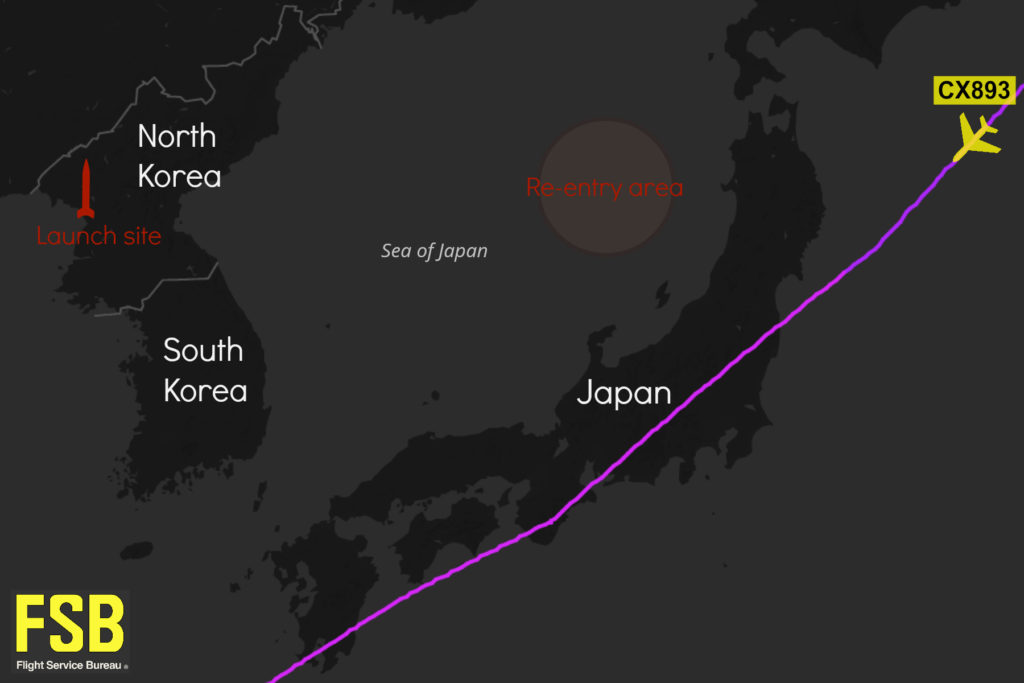

The risk for aircraft was from falling debris from rocket staging, or even a complete failure of the craft.

The Notam…

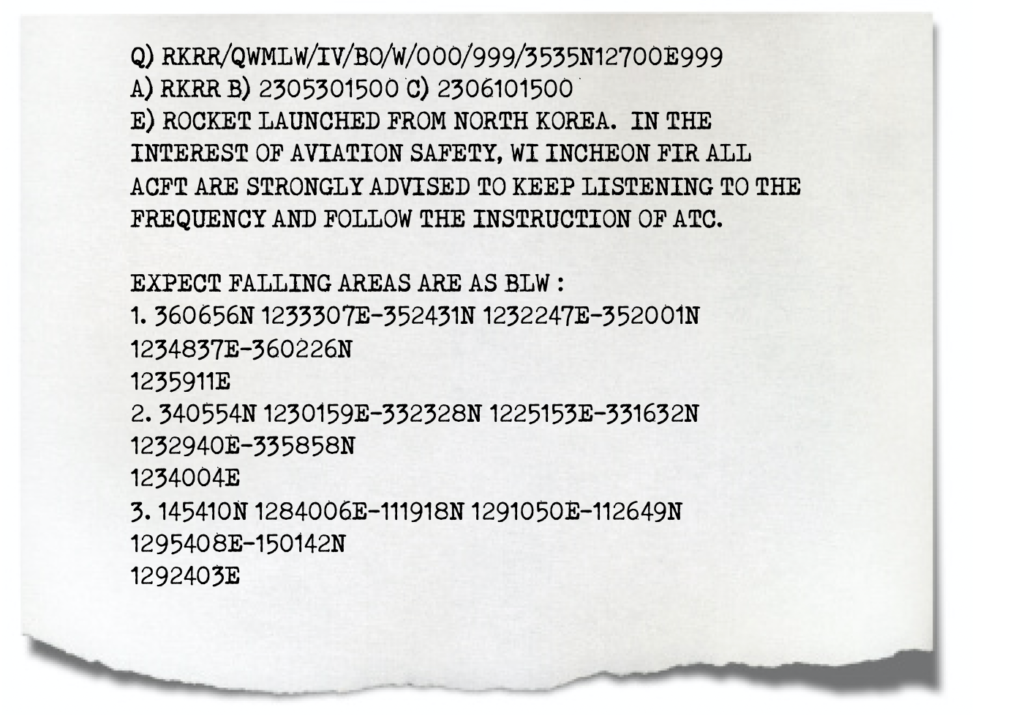

On May 29, South Korea (the RKRR/Incheon FIR) published the following Notam (which has since been cancelled):

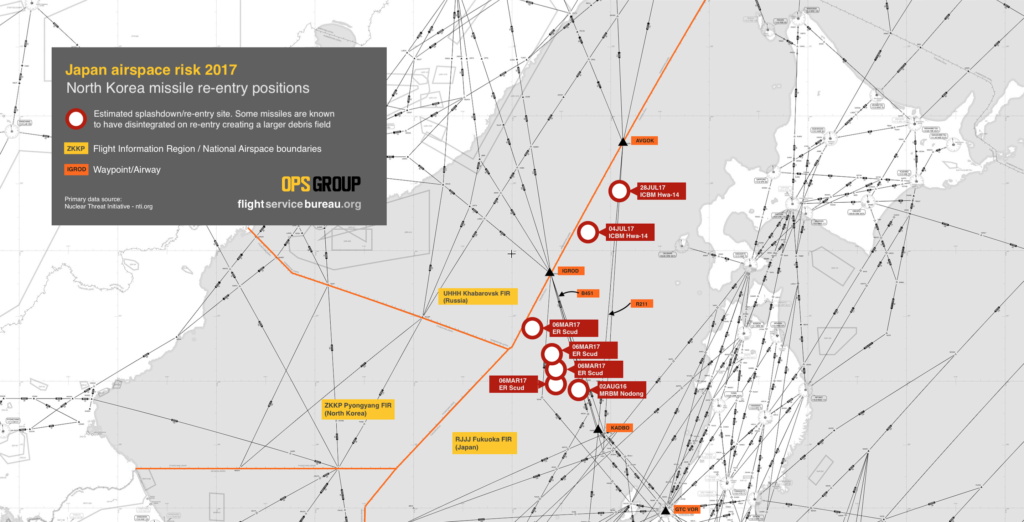

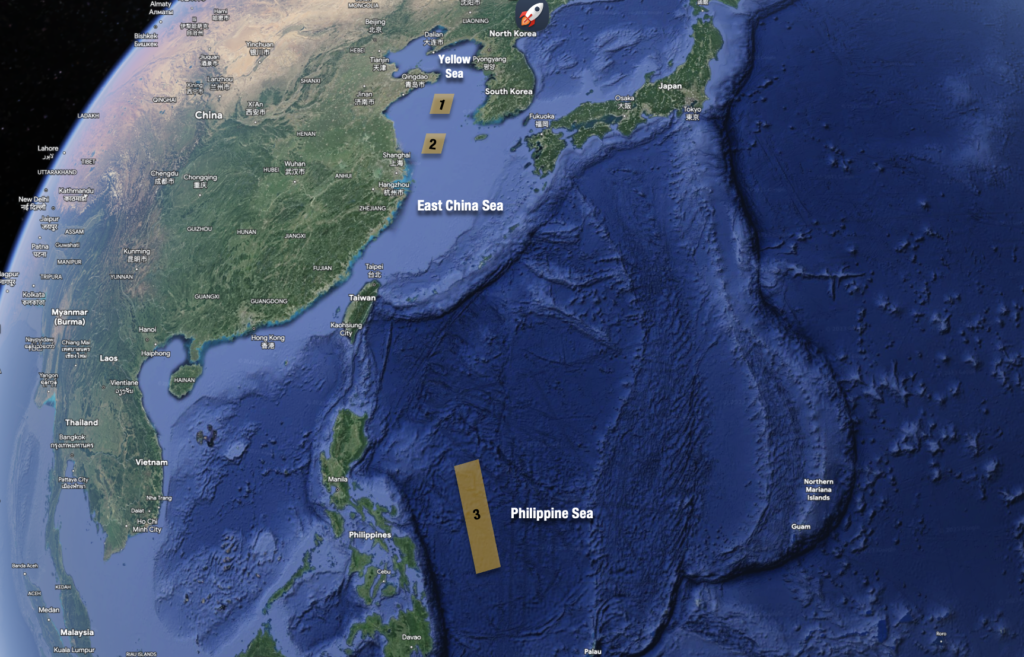

There were three major hazard areas – portions of the Yellow Sea, East China Sea and the Philippine Sea.

There were three major hazard areas – portions of the Yellow Sea, East China Sea and the Philippine Sea.

Don’t think in capitalised type-written coordinates? Neither do we. Here’s what that looked like on a map:

The official advice was avoid them completely, if practical. Otherwise, to listen out to ATC for potential updates.

The official advice was avoid them completely, if practical. Otherwise, to listen out to ATC for potential updates.

The Plot Thickens…

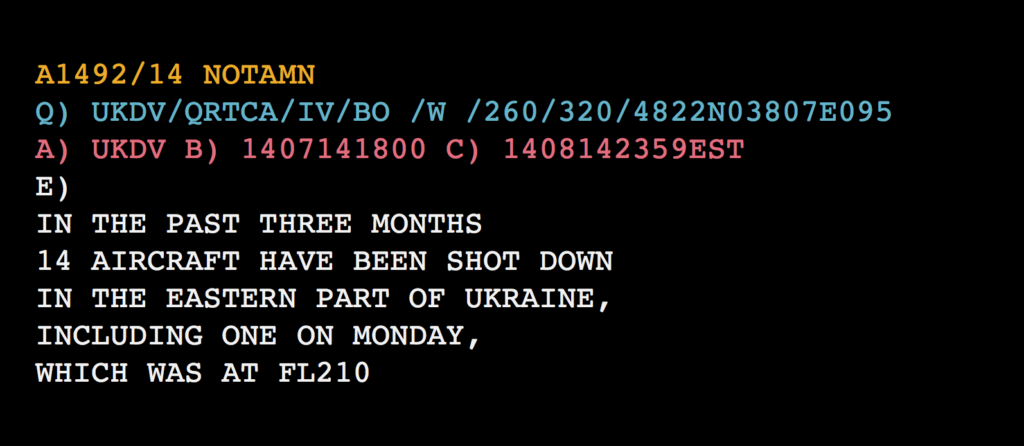

Given the current state of affairs, any launch is politically sensitive and risks far greater political fallout. Japan has been especially vocal in denouncing them saying that they ‘threaten the peace and safety of Japan, the region and international community…’ They have vowed to shoot down any satellite or debris if it enters Japanese territory – important note: there are currently no airspace warnings for air defence activity anywhere in the RJJJ/Fukuoka FIR. With the best intentions, history has shown this type of activity can inadvertently put civilian aircraft at risk.

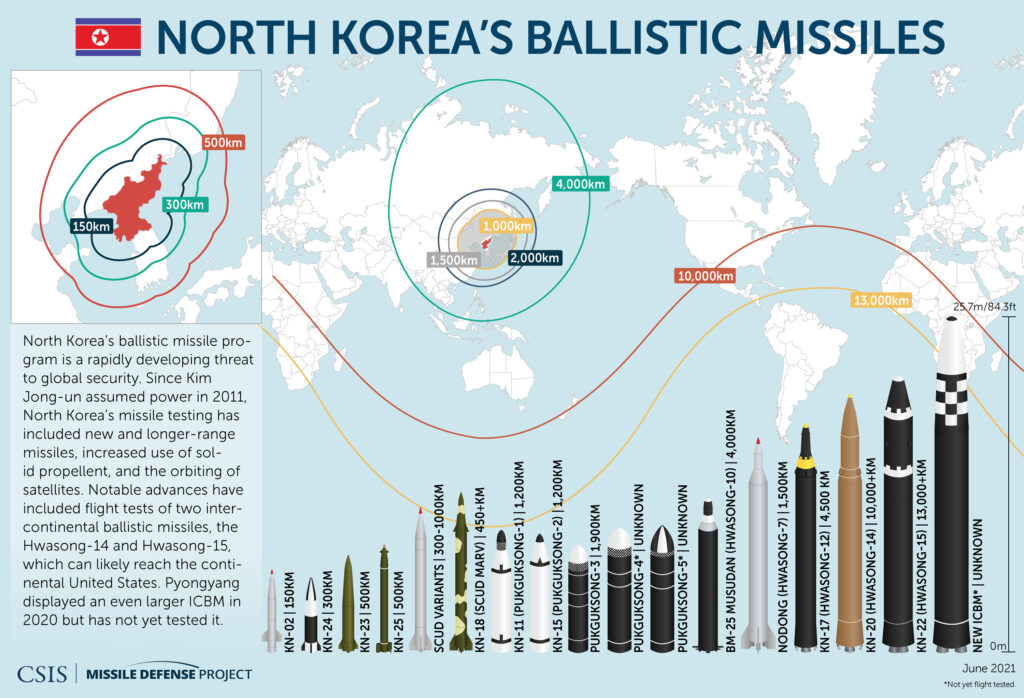

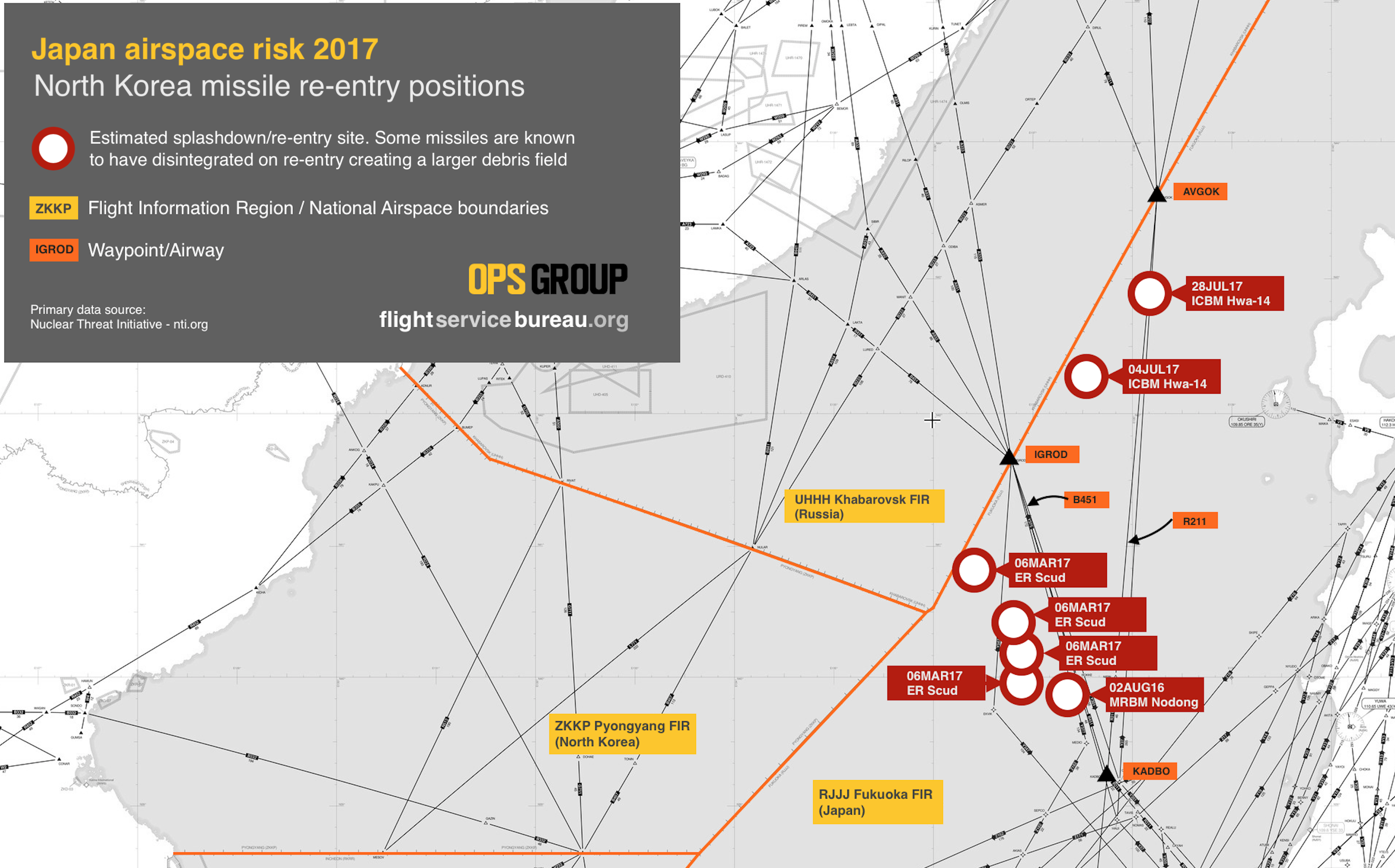

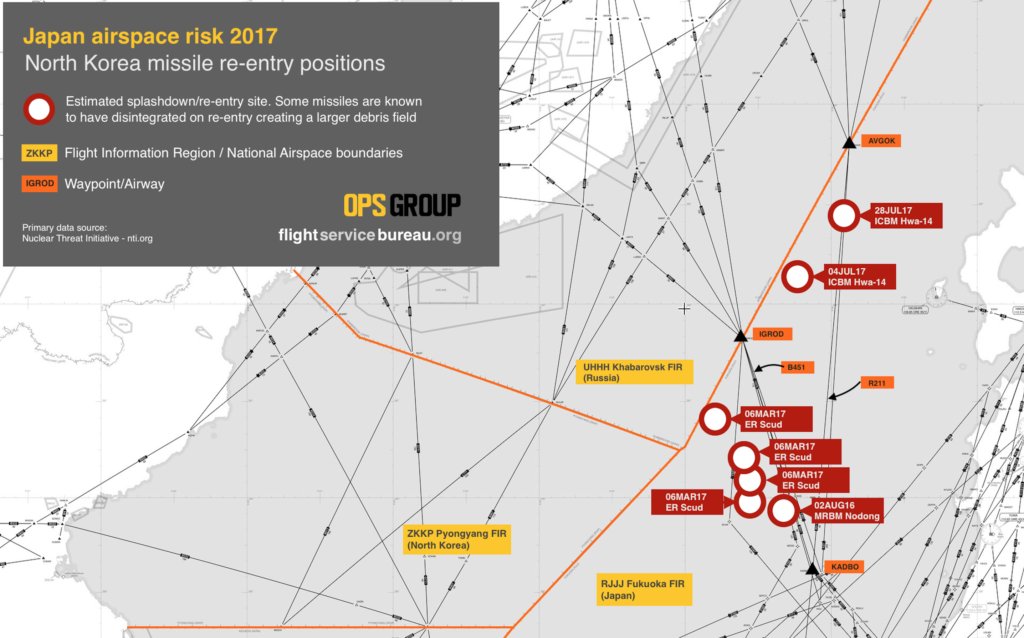

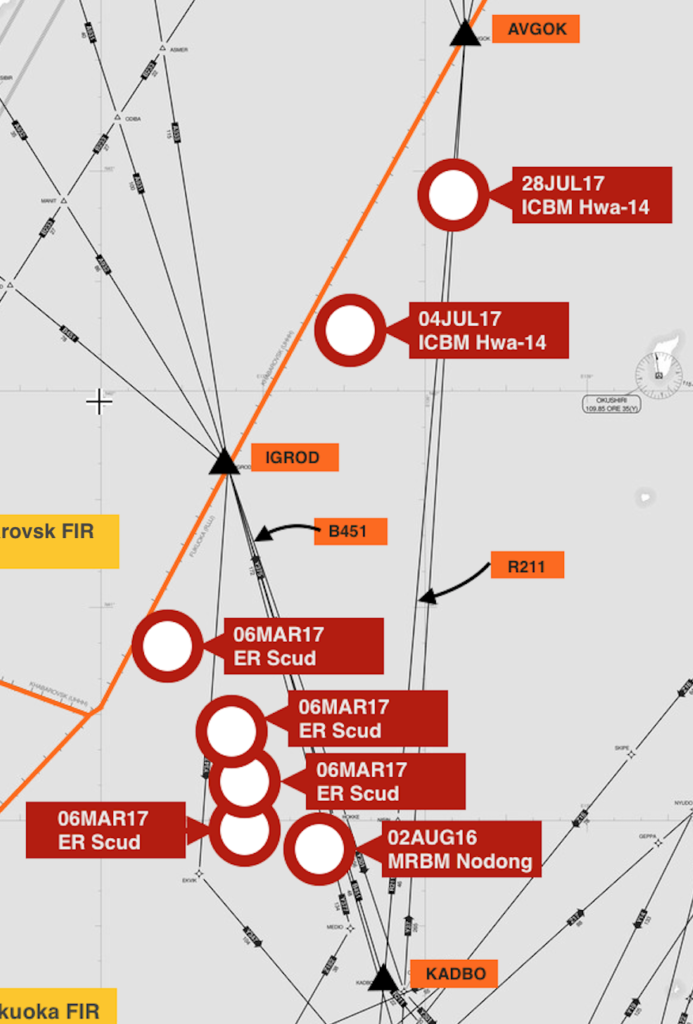

It’s no wonder too – there is a well publicised record of North Korean missile launches coming uncomfortably close to Japanese territory, often landing well into the Sea of Japan.

Political Posturing

It’s unclear whether these are genuine attempts to put a craft into orbit, or more simply a political statement to flex North Korea’s ballistic missile capabilities. If subsequent launches were successful it would be North Korea’s first foray into space ops. However, it comes at a time when there have been large scale live-firing military exercises near the North Korean border by South Korea – part of a seemingly constant cycle of diplomatic muscle flexing that seems to characterise to the region – and as such we may need to take things with a grain of salt.

From an airspace perspective though, these launches should be treated as real hazards. At the very least because it is better to be safe than sorry.

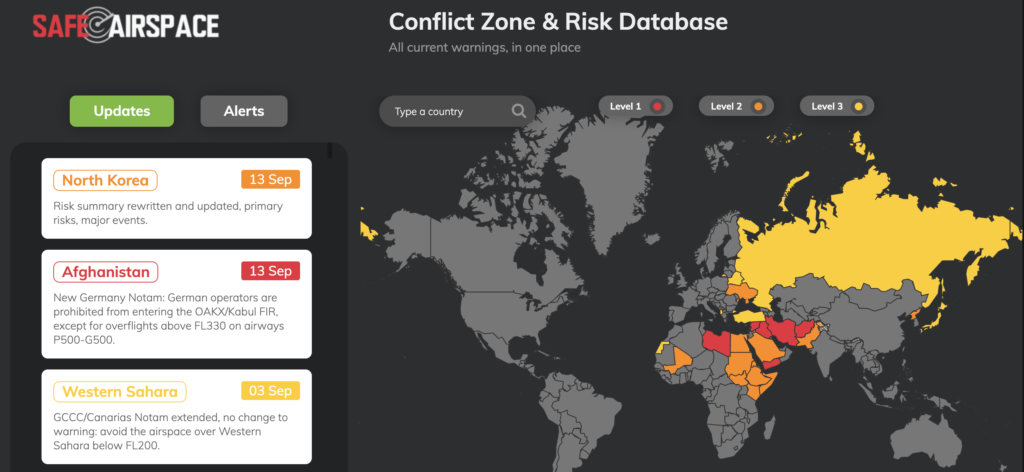

We’ll continue to report on any changes as they emerge. Many of these risks are well publicised, and safeairspace.net is a great place to start for that info.