Aviation has always been a reactive industry – because it needs to be.

Over time, forces beyond our control have continued to influence the way the industry moves forward and the way we operate.

For the past eighteen months, our reactive energies have been focussed primarily on one thing – a global pandemic. But it is important that we continue to react to other changes too – particularly when it comes to security, and the types of threats that we face are evolving.

As the industry begins to recover from Covid and press on into the decade, here are some of the biggest security threats that it will face.

Operating Near Conflict Zones

While the lines between aviation and politics are often blurry, they undeniably intersect. The point is that regardless of which side we choose to take, we continue to operate aircraft over or in close proximity to active conflict zones. Which means risk.

The past eighteen months have shown that conflicts can erupt with very little warning in busy flight corridors and with significant dangers to the aircraft flying above them.

This was the case last year in Azerbaijan, where almost all west/east bound airways were closed by the conflict below. Only months ago, Israel’s Tel Aviv FIR was heavily affected by widespread rocket attacks while just this week, Afghanistan’s Kabul FIR has been left with no ATC services following an overwhelming Taliban offensive.

More than 3000 rockets affected Israeli airspace over an eight day period in May 2021. Aircraft were immediately under threat from not only them, but widespread use of high-tech air defence systems.

Things can change quickly and the problem isn’t going away in a hurry.

But perhaps more concerning is that the aviation system relies on the sharing of information to keep us safe up there (and ICAO Annex 17 demands it). But practically speaking, concerns remain over inadequate government intelligence sharing, especially in states involved with conflicts.

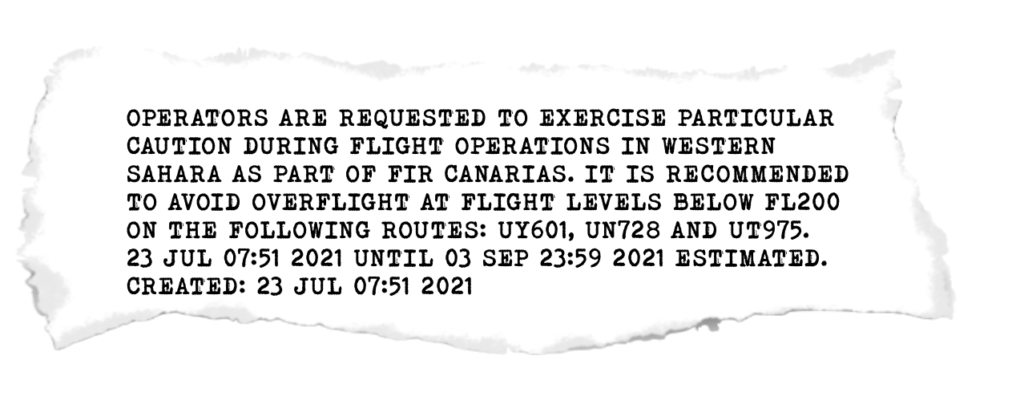

Your flight is tomorrow and you’re not familiar with the politics of Western Sahara. Here’s what the notams have to say. Is it safe to overfly?

Until things change, reliable risk assessments will remain a challenge firmly on the shoulder of operators – and these will rely on timely, unbiased and accurate information. As we have often seen, that can be very hard to get.

Terrorism

Unfortunately, aviation will continue to be a target for terrorism.

While security at airports remains tight, the challenges of breaching it have led terrorist groups to develop new ways of targeting aviation interests. While large-scale attacks the likes of 9/11 seem more far-fetched with today’s protocols, there is a renewed interest by terrorist groups in attacking so-called ‘soft targets’ – primarily aircraft in flight or airports with poor security infrastructure.

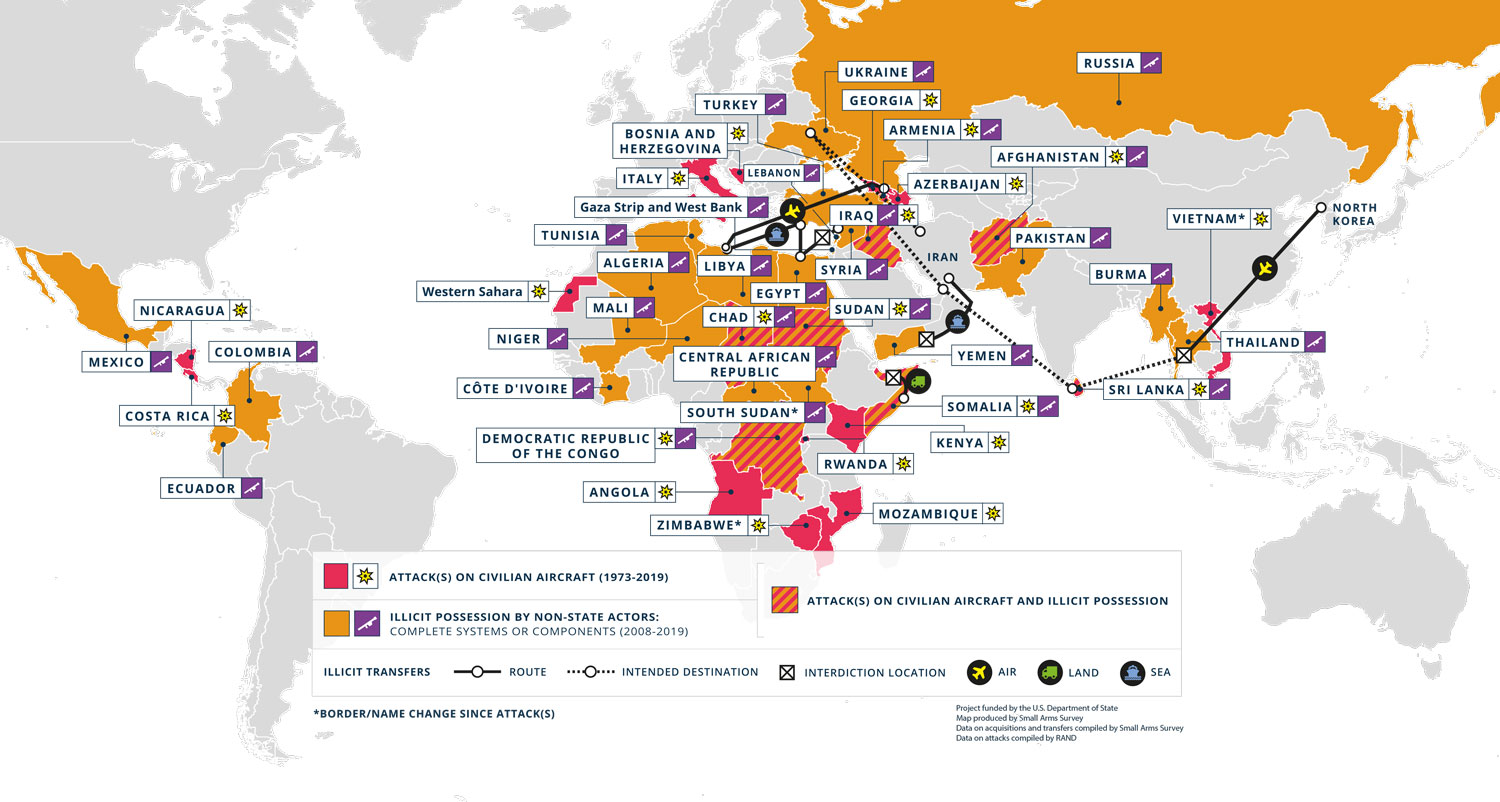

To make matters worse, non-state actors and large terrorist organisations (such as ISIS and Al Shabaab) are encouraging smaller groups or even just lone-wolf individuals to attack by proxy, which makes the threat difficult to prevent. These attacks don’t need obvious leadership, and can be accomplished by low-tech means. Weapons such as rockets, mortars and man portable air defence systems (MANPADS) are of particular concern.

Non-state actors with access to MANPADs are spread throughout the world. Courtesy: US Dept of State.

Recent events at ORBI/Baghdad Airport serve as a good example, where multiple rockets were found stashed on nearby rooftops overlooking the airport.

Civil Unrest

In the past eighteen months, we’ve seen countries around the world suddenly erupt into periods of civil unrest. While beyond the realm of airspace warnings and Notams, the effects on crew safety on the ground can be dramatic.

While strikes and peaceful demonstrations can cause little more than inconvenience on the airport commute, it is when things get violent that the danger emerges.

Two examples spring to mind this year where the security situation on the ground changed rapidly and without warning.

The first is Myanmar where in February a military coup saw nationwide protests. Clashes with military police eventually turned violent with mass civilian casualties in the capital, Yangon. Disruptions continue there to this day.

The second is South Africa last month where a political and legal dispute led to widespread rioting and looting and became the worst violence that South Africa had experienced in many years.

Violent clashes between protestors and military resulted in mass casualties in Myanmar earlier this year.

Given the abundance of uncertainty that seems to characterise the modern world, it seems naive to believe that civil unrest is going anywhere in a hurry. Recent events have shown that even away from airports, aviation professionals continue to be at risk.

Cyber Threats

While the aviation industry has developed a strong track record of security practices from physical threats, it has struggled to keep pace with digital ones.

Studies have revealed some alarming numbers. EASA for instance have reported an average of one thousand reported cyber on attacks on airports every single month, while systems at airports in Israel fend off up to three million attempted breaches per day.

Unlike other industries, aviation is particularly vulnerable to cyber-attacks because the consequences can be so catastrophic. Successful attacks could literally cost lives.

Only two things are needed to open the doors to a cyber attack: a vulnerability and a pathway. We’re heavily reliant on countless connected systems that have to operate in real-time and with super-high reliability. Many of them are safety-critical, and they have to be protected.

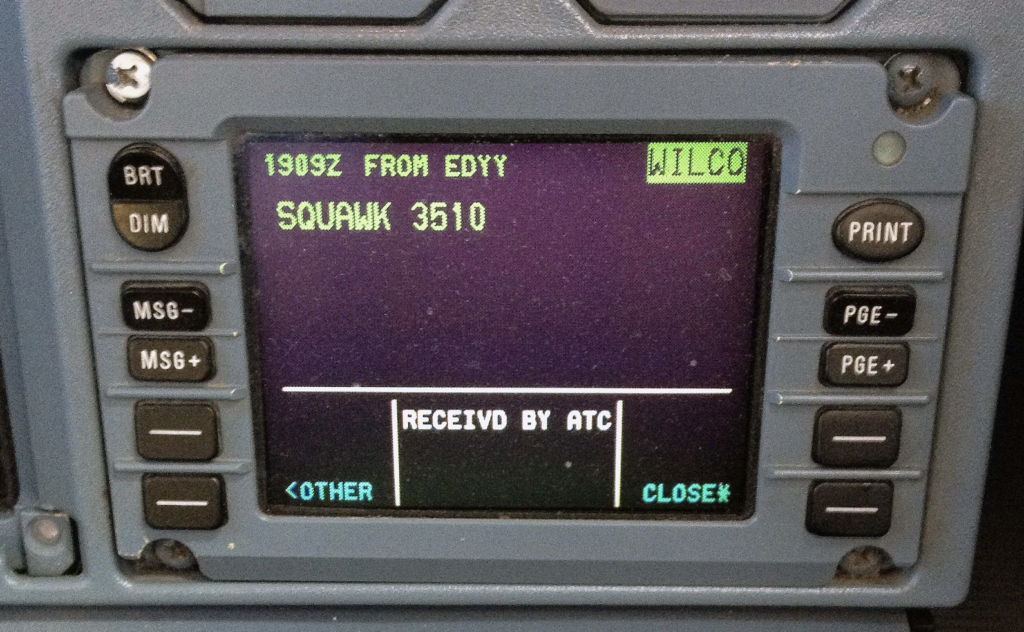

Have a ponder for a moment about just how far that rabbit hole can go. Here’s a few suggestions just to get you started: Primary radar, secondary radar, EFBs, ADS-B, GNSS, Datalink, ACARs, even Fly-By-Wire. Heavy, heavy hitters in the safety game. This is before we even go down the road of the pilotless aircraft.

Safety critical systems such as CPDLC could potentially be targeted by cyber criminals.

As technology continues to improve our efficiency and make our jobs easier, it is also opening gateways for those with malicious intent. Aircraft are becoming smarter and more connected, but arguably also more vulnerable to attack.

The challenge in years to come will be how to protect these critical systems, or at least limit the impact when they are attacked.

Human Trafficking

The unlawful act of transporting people around the world in order to benefit from their labour or exploit them in other ways continues to be a global phenomenon. Particularly when they are suffering from economic hardship.

Recent studies have shown that as many as 700,000 people become the subjects of human trafficking every year, with reports from over 127 countries worldwide. It is aviation that is often the vehicle for this malicious trade. These unfortunate people are often travelling with forged or stolen documents, and may be under duress from the people they are travelling with.

It’s an ongoing problem. ICAO itself is directly involved in efforts to address it through better training and an understanding of where in the world the worst hotspots are. However it is likely to remain a threat to aviation security for many years to come.

Threats to aviation security aren’t new, but our reaction to them needs to be.

Moving forward our response to security in the industry must continue to evolve to meet the threat, regardless of what other industry pressures we find ourselves under. Undeniably, our safety and that of our passengers will depend on it.