On March 1, several aircraft reported erroneous TCAS TA and RA alerts while on approach to Runway 19 at KDCA/Washington. All aircraft correctly followed avoidance procedures, and no loss of separation occurred. Six of the incidents occurred within eleven minutes of each other.

⬆️ shared with permission, courtesy of VASAviation.

What has followed is speculation – who, or what, was responsible? It is an answer the FAA is actively seeking.

TCAS interference is rare but can occur. There are several plausible explanations including ground clutter and reflections, software issues and unintentional radio interference.

However, it would be hard to deny that these alerts came at a sensitive time both for operations at the airport following the mid-air collision over the Potomac River, and across a broader tapestry of concern for aviation safety across the US NAS given recent events.

Which begs an important question – can TCAS actually be tampered with? Is it possible these events were an act of criminal mischief or other mis-intent? While remote, a little-known alert issued just weeks ago by CISA (the part of Homeland Security responsible for US cyber and infrastructure security) suggests it is indeed possible.

Published on January 21, CISA discussed two flaws in TCAS design that leave the system vulnerable to malicious cyber-attacks – one of which they deem a high, almost critical vulnerability.

In event that such an attack occurs, criminal interference could generate fake targets on an aircraft’s TCAS display and even disable resolution advisories.

The problem is that bulletin is quite technical. So here is a break-down of what it says in plain, simple language.

The Bulletin

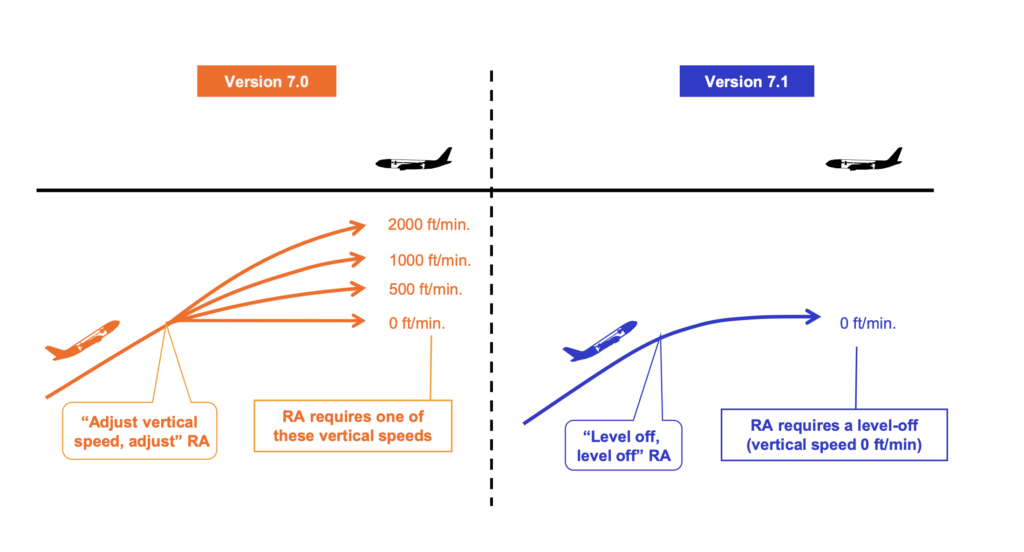

There were essentially two risks identified for TCAS II Versions 7.1 or older.

1. Fake Position Signals

It is theoretically possible to broadcast a spoofed aircraft location to another target.

This could be achieved using specialised radio equipment where potential attackers could send fake signals to aircraft, causing the appearance of non-existent targets on TCAS displays, along with the associated warnings.

In other words, crews would effectively be chasing shadows.

As TCAS II systems rely on transponders that may not be able to adequately validate the data received, they remain vulnerable to unauthorised signals. The bulletin describes this risk as a reliance on ‘untrusted inputs’.

Read the report and you’ll see something called a ‘CVSS score.’

CVSS stands for Common Vulnerability Scoring System, and it is basically a danger rating for flaws in computer security. It is a measure of how serious a vulnerability is. Factors include the method of attack, the access required and the potential impact.

It is represented on a scale of 0 (non-existent) to 10 (critical).

The issue of fake position signals has been given a CVSS score of 6.1.

Perhaps more concerning is that the report advises there is no way to actively mitigate this threat with existing TCAS technology. The equipment required is accessible to the public. Therefore this threat is the most likely suspect of any erroneous TCAS interference occurring today.

2. No TCAS RA

This affects some older TCAS II systems using transponders with outdated technical standards.

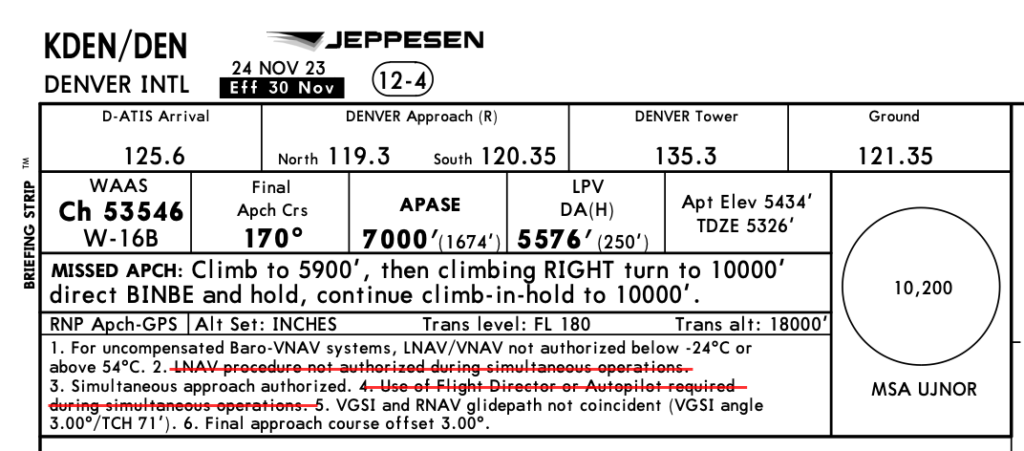

It is theoretically possible for an attacker to impersonate a ground station and send a special request that lowers a system’s sensitivity settings. A TCAS sensitivity level command does exist, envisaged to reduce nuisance alerts at some airports.

This could be used to maliciously adjust sensitivities to the lowest setting and even disable a resolution advisory completely.

The threat has a concerning CVSS score of 8.1 – highly vulnerable to exploitation, but would require a high level of expertise and technology to carry out.

Fortunately, in this case there is a way to mitigate the problem – by switching to ACAS X, or upgrading your associated transponder to more recent technical standards.

There is no indication that this has vulnerability has ever been exploited.

While unlikely, the CISA bulletin proves that TCAS could be vulnerable to malicious interference.

So, could the aircraft at KDCA have been hacked?

It’s unlikely, but CISA’s report indicates it’s possible. And a new expert analysis of events at KDCA by Aireon seems to agree. In their published report they found that ‘it is possible the intruder was airborne or related to a ground-based transmitter used for testing or spoofing.’

Why does this matter?

The industry must remain responsive to security threats that are becoming increasingly sophisticated and designed to exploit vulnerabilities in safety critical systems.

The recent industry-wide interest in GPS interference spanning from the inconvenient, to major degradations including the loss of EGPWS protection, ADS-B tracking and navigational accuracy is a startling testament to this fact. This is all possible because of existing system design.

Since the events of September 11, passenger screening and security protocols have undergone a revolution, and it’s now much harder for bad actors to carry out conventional attacks. But there are still risks associated with malicious attacks that could potentially be achieved remotely – and cyber-interference seems an obvious choice.

…although the last one is still recommended by the FAA.

…although the last one is still recommended by the FAA.