Aviation is full of procedures. We fly by them, sometimes we kind of live by them. But other times there are situations where we need to disregard them. So when is it ok to throw the rule book out the window?

In an airplane, never.

In the literal sense anyway, given the risk of opening a window mid-flight and getting sucked out. But what about in the less literal sense?

Procedures are not there to stop us just doing whatever we want. They are there to keep us safe, to make sure everyone is operating to the same standards and to provide pilots with a guideline of what they should do in *most situations.

Why the asterix?

I will come back to that. But for now, that reasoning makes sense. If every airplane did what it wanted, flew how and where it wanted, the sky would be a messy mass of chaos. So, we have procedures and we have them so we know what to do, when to do it and how to do it.

More importantly, everyone else knows as well. Which brings us back to the “most situations” comment.

We cannot expect there to be a procedure in place for every possible event. They are there to offer guidelines and standards, but they are not designed to cover everything.

And they are definitely not supposed to remove the need to think.

So what should we think?

Well, thinking about situations where we might be without a procedure, or where there is a procedure but it no longer leads to a safe outcome is a good place to start.

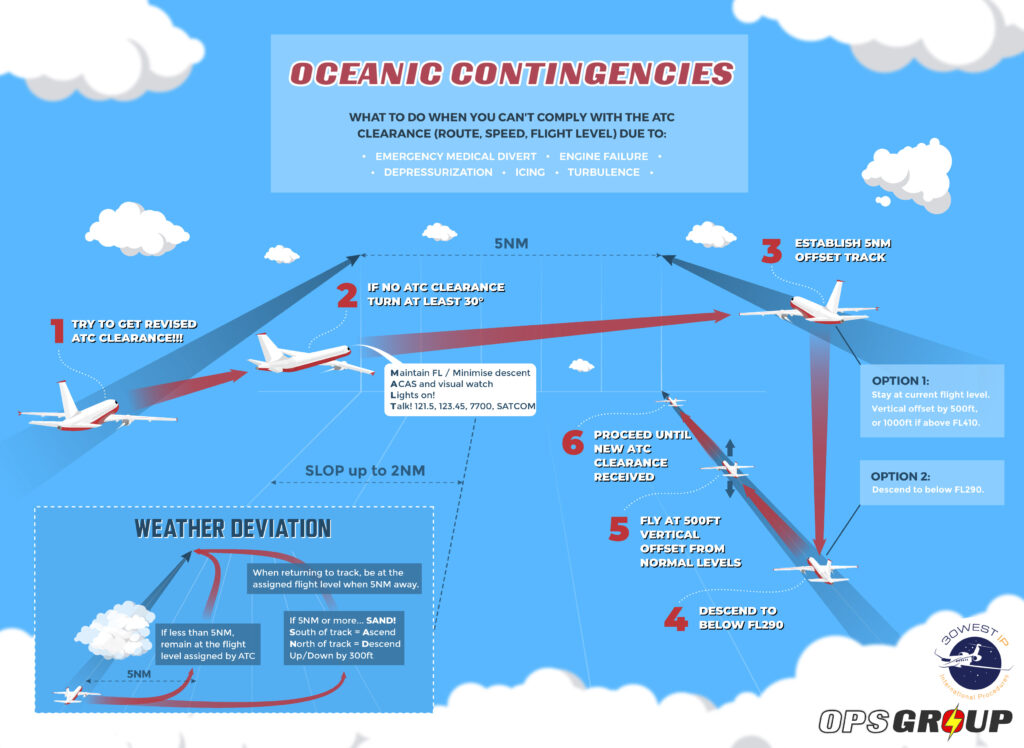

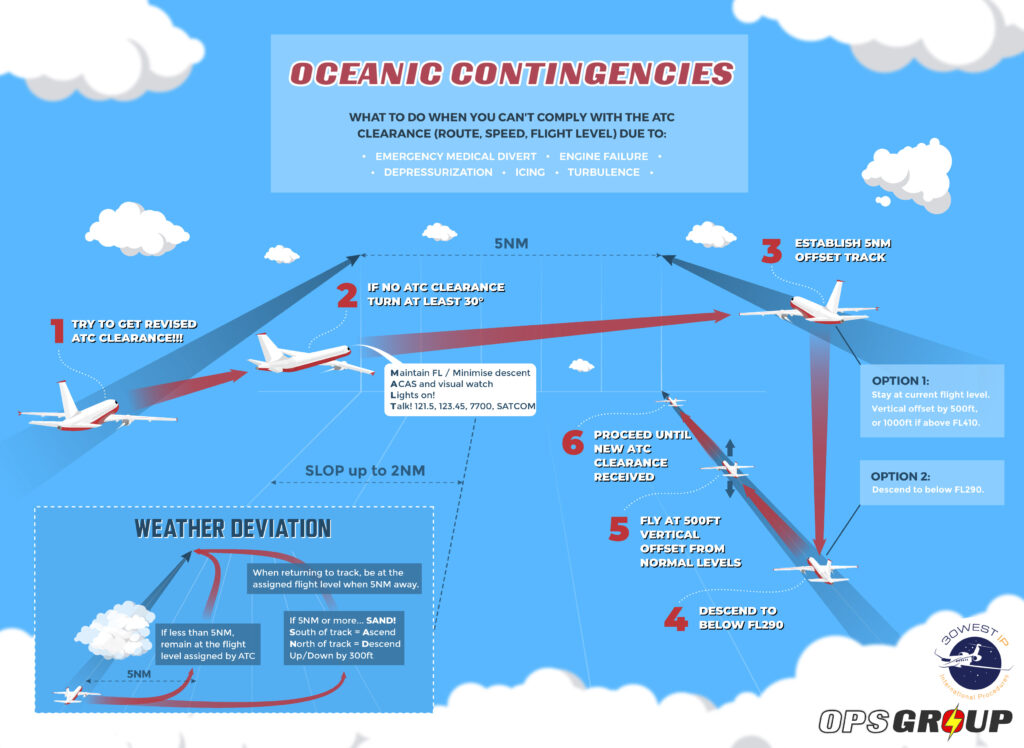

Let’s take a look at ICAO Doc 007 – the “bible” for the North Atlantic. It is quite clear on a lot of things – for example, what the contingency procedures are if you experience some sort of emergency while flying in the NAT.

We are talking some busy airspace out there, with a lot of aircraft flying on specific tracks, and so the last thing you want is aircraft barreling across them setting off TCAS warnings as they zoom off on a diversion.

So NAT Doc 007 lays out some procedures to follow. Things like turning 30 degrees off track and offsetting 5nm. And one that says –

“When below FL290, establish and maintain 500’ vertical offset when able and proceed as required”.

Ok, great, it is pretty clear. Get yourself down to below FL290, establish on your offset, and now go where you need to go.

But…

What if our emergency is a decompression, and we are right out in the middle of the NAT where routing at 10,000ft the whole way to an airport might turn into a fuel problem?

Do we still need to get to FL95 before starting a diversion?

There might not be a black and white, right or wrong answer, but this is the point – there are situations where there isn’t necessarily a procedure telling us what to do, or when to follow another procedure.

So this is something we should probably be thinking about a bit more. The “What If?” things that could happen.

So, what is the rule for breaking procedures?

Is there sort of a checklist for when we can, can’t, ought to or must? Why isn’t there a rule for every time you are allowed to break a rule?

Well, the reason is no-one can think through every situation, and more importantly they shouldn’t try to!

The day pilots can only do something if a procedure tells them to is the day you might as well replace them with a computer. We need to retain the skill of weighing up risk and reward, consequence of actions, because there are so many situations out there which are not going to be black and white.

NAT Doc 007 document actually states quite clearly several times –

“The pilot shall take action as necessary to ensure the safety of the aircraft…”

And this goes for any procedure, any rule, anytime you are flying.

Just because the book says “No, don’t do that!” never means you cannot do it if it is what you need to do to maintain safety.

The tragic Swissair Flight 111 accident is often raised in CRM discussions as an example of when following procedures to the book might not lead to a safe outcome.

But…

Not following procedures because you think there is a quicker, better, easier way to do something is probably not the best idea either.

A Qantas pilot experienced “incapacitating” symptoms after a technical malfunction where they decided to cary out their own troubleshooting, rather than following the checklist.

So, having a good reason to not follow a procedure is important because you are going to have to justify why you broke the rule. If you need to break it for safety then break it, but the key seems to be having a valid, justifiable and safety related reason.

That is airmanship, and that is why the Commander has final authority. It is also a cornerstone of our pilot licence that we “agree” to accept the ultimate responsibility for the safety of the flight.

Why are we even having this discussion?

Possibly because we sometimes forget why we have procedures in the first place.

Unfortunately none of us are immune to this. I can remember several times in my career when procedure-following took over from common sense. The time when we shut down an engine with 10 meters of taxi left, ran out of steam, and had to be towed the last 9… But hey, we still ticked the one engine out taxi box.

So, all of us stepping back and considering why the procedures are there, and then what we might do when we find ourselves potentially having to operate outside of them, is important.

Which brings us back to the debate about FL95 over the NAT.

Different folk might answer this question differently. It is going to depend on the day, on you and on the situation, and there probably isn’t a definitive answer to be given.

What is clear is that at some point in our flying career we will all probably find ourselves in a situation where there is no procedure, no clear cut answer, no simple solution, and this is where our experience, airmanship and judgement will really be put to the test.

When we end up in that situation we should’t be asking “What is the risk of me getting into trouble if I do?” but rather “What is the risk to my safety if I don’t?” because all the procedures we fall back on were not put there to be blindly followed, and were not written into stone to keep you out of trouble – they are there to be thoughtfully followed when they keep your aircraft out of trouble.