How much radiation are we getting zapped with as crew, and what sort of levels should we be concerned about?

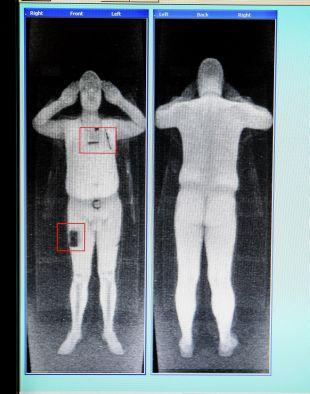

The Airport Security Scanner

Most pilots have probably experienced rather overzealous security scanners in an airport. You know the ones – when you go through, it beeps. You remove the watch you forgot to take off. It beeps again. You take your jacket, shoes, tie off. It still beeps. Now you’re wondering if you’ll need to strip down like this South African Airways pilot did…

More concerning than any radiation levels

Anyway, it is frustrating, but it is not really a big deal radiation-wise. One dose of the airport scanner is 100,000 times lower than the average annual dose we get from natural background radiation and medical sources. It actually delivers around 0.1 microsieverts per scan which is 100th what a standard chest x-ray delivers.

For comparison, every banana you eat contains around half a gram of potassium-40 (an ionising radiation source) which means eating it is the equivalent of 1000th of a chest X-ray in terms of the radiation dosage. The granite counter top you prepared your lunch on is also dosing you. While if you live in the UK you are getting about 2.7 millisieverts of radiation annually just by being there because it is one giant granite counter top under your feet.

Bananas are a great source of (radioactive) energy

So, no, we shouldn’t be worried about radiation from airport scanners. But given that every minute on an airplane is equivalent to one airport scan, should we be worried about that?

Flight Risk

When you fly you are exposed to low levels of radiation – from some of the onboard equipment, to the fact you are way nearer space and all the cosmic and UV rays swilling about up there.

UV radiation is what we protect ourselves against by not destroying our friend, the Ozone Layer, and with all the SPF suncream we slather upon ourselves. The ozone layer sits around 10-15 miles above the ground (so our airplanes stay below it), and it blocks out a good whack of UV-B, all of UV-C and some UV-A.

Now, that *some is the reason why we should be slathering more sunblock on ourselves when we fly, because the ozone layer and our windscreens help, but not enough. A study showed that the amount of UV radiation the pilot seat (and you in it, presumably) gets smacked with when flying for under an hour at 30,000 feet is equivalent to a 20 minute tanning bed session.

Studies also show the rates of skin cancer in pilots and cabin crew are significantly higher than the general population. So, you need to be careful. Plus it makes you wrinkle more.

- Wear sunblock (decent UV-A and UV-B ones)

- Get decent sunglasses with UV protection lenses because your eyeballs are damaged by it too! Polarized sunglasses help reduce glare, but don’t necessarily provide more UV protection (and they mess with the screens).

- Check them moles (if you’re a moley sort of person) – it isn’t just areas exposed to direct sunlight which can be at risk.

In fact, going back to the sunglasses point, IFALPA have a very handy handout on the ‘Ocular Hazards of UV Exposure’. It is basically ‘scary stuff, bad stuff, scary stuff’ and then a “get sunglasses that have a UV absorption up to 400nm/ 100% absorption’.

There is no evidence of people sunburning in airplanes

Cosmic Vibes

Cosmic radiation is high-energy charged particles – x-rays and gamma rays which come from stars, like our very own sun. It differs to UV radiation in that it is higher energy and ionising.

We don’t like ionising radiation because it causes damage to our squidgy little insides.

The closer to space we get, the more cosmic radiation we are exposed to, and the higher the latitude the more we get as well, which means those high altitude, Polar flights are the ones to really monitor.

The Northern Lights displays we see, despite their “radioactive” green colour actually do not emit any radiation that reaches us. Although, if you were up there, in it, it probably wouldn’t be great for you.

What are the numbers looking like?

The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) basically classify aircrew as ‘Radiation Workers’ and recommend a maximum of 20mSv a year averaged over 5 years. So a maximum of 100 mSv in 5 years.

The average person in the US receives up to 3mSv, with a recommended dose of 1mSv per year. Anything between 3 and 20mSv is considered moderate.

So, how much are we getting?

Well, heading from the east to the west coast of the USA you probably get about 0.035mSv. Not a tremendous amount if you’re a passenger, but what about if you are doing flights several times a week?

2 sectors a day, 3 times a week, plus or minus a few for holidays, and you could be heading towards something in the region of 10mSv which is higher than normal but still in the moderate (and acceptable) range.

If you are flying from Athens to New York – a flight likely to take you along a relatively northerly route and at a flight level of 41,000ft or higher, then the 9 to 10 hours airborne are going to dose you up another 0.063mSv – 0.63mSv per 100 block hours.

A study carried out in 1998 suggested the average crew member flies around 673 block hours, getting an average cosmic ray dose of 2.27mSv, while the annual cosmic ray dose for a long haul Captain was calculated at around 2.19mSv.

Ok, that was back in 1998, but as far as we know the levels of cosmic rays haven’t increased. Our block time might be a few hundred higher, but still well within limits on the radiation dose front.

Sunglasses always necessary

How can you monitor it?

Airlines and operators should monitor this for you, but if you want to keep an eye on it you can via various apps out there in the mobile phone world.

CRAYFIS is an app developed by scientists to help monitor the amount received via the pixels in your smartphone screen.

Apps like TrackYourDose have options to plug in a route and uses average flight paths to help you monitor your dose on specific flights and days.

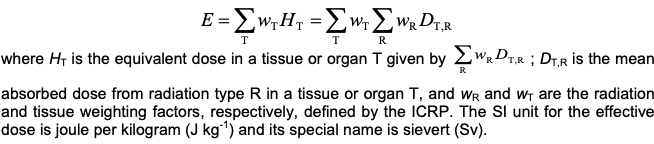

Or you can work it all out yourself using this handy little formula.

Maybe just use the app

So, should we be worried?

The figures suggest no.

A study of 10,211 pilots carried out in 2003 also supported this, with skin cancer showing slightly higher incidences.

So unless you are flying an excessive number of long haul Polar Flights, the overall the radiation dosage received by air crew is higher than the average ground dweller, but remains within acceptable limits.

That space weather is likely to have more of an impact on your HF than it is you.