Flying over large expanses of ocean, one might assume the cockpit would be a quiet, boring space with little more to do than to speculate about company rumors or constantly graze on the galley snacks you long ago promised yourself you’d stop eating. But the reality is that to ensure a safe and compliant oceanic crossing, the tasks involved can be intensive and the cockpit can be a busy place!

Plotting and monitoring your route over the ocean – or any remote area for that matter – is one of those vital tasks necessary to ensure safe navigation. And with some familiarization with up-and-coming technology and hands-on training, plotting can serve as both a confirmation of aircraft navigational abilities and a last ditch resort if such capabilities fail.

Why We Plot

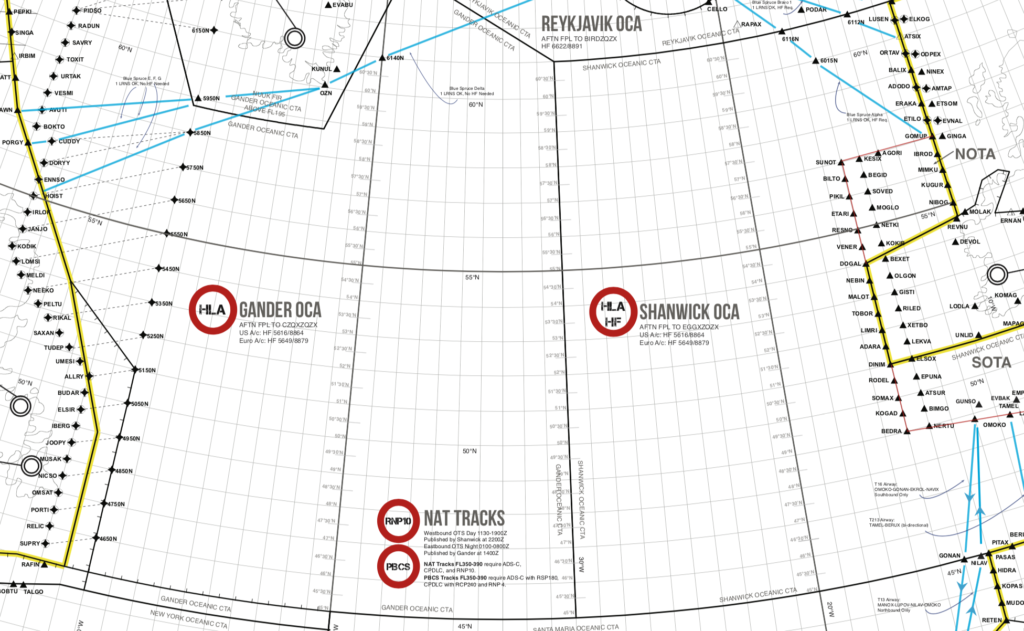

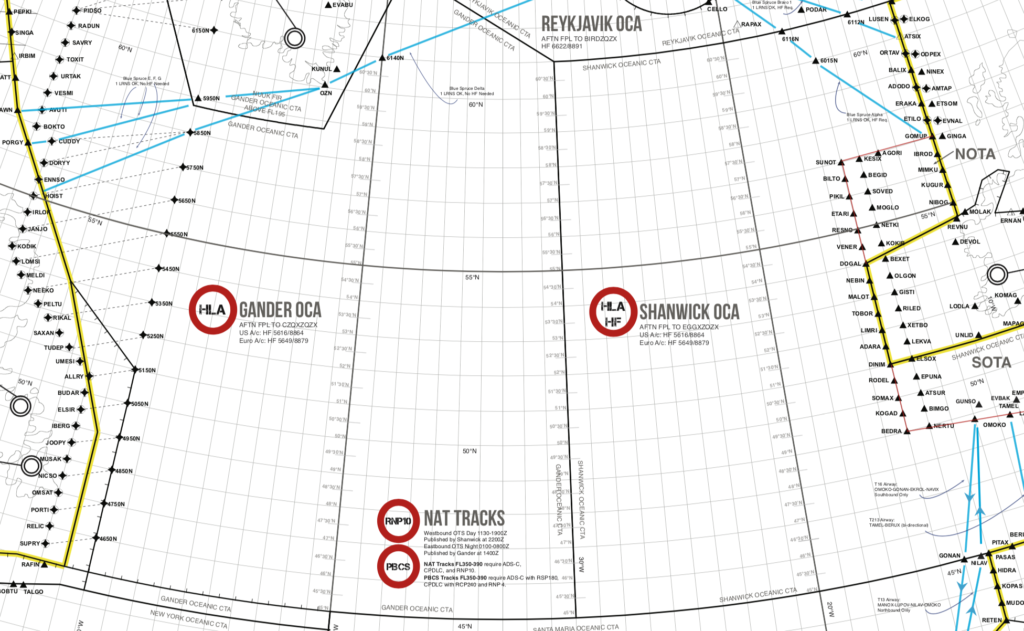

Legally speaking, the crew of any turbojet that flies a route that exceeds 725 nm from “the service volume of an ICAO approved ground based navaid must perform plotting procedures as a way to generate a ‘reliable fix‘ of its position once per hour (the distance decreases to 450 nm if flying a turboprop),” explains Guy Gribble, General Manager of International Flight Resources.

With the breadth and reliability of most modern aircraft long range navigational systems (LRNS) and flight management systems (FMS), it may seem archaic to manually plot an oceanic course. But studies have shown that plotting greatly reduces the chances of flying off course and causing a gross navigational error. FMS’s are NOT infallible and the pilots operating them even more so!

Plotting not only assists in ensuring you are flying your cleared AND verified route, it serves as a system of checks and balances when reviewing your (and your co-pilot’s) inputs into the FMS. In the event of a partial or complete loss of navigational abilities, the plotting chart also works as an emergency form of dead reckoning. And lastly, combined with the Master Document, the plotting chart is the trip’s legal record of compliant (or lack thereof) oceanic navigation if a state authority were to review or investigate the trip for any reason.

Requirements

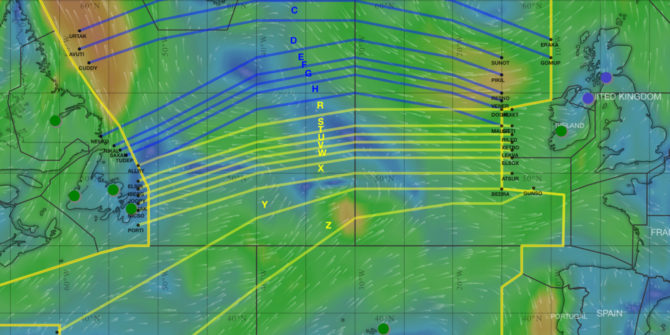

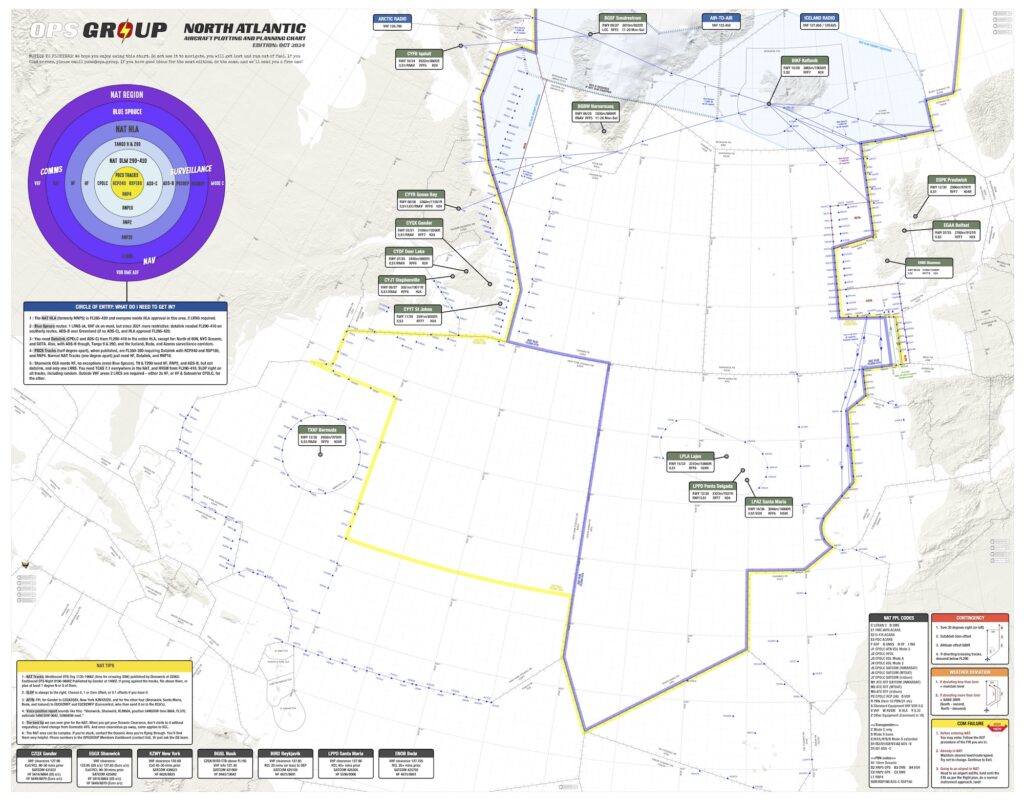

The first requirement begins with the plotting chart itself. The chart must be oriented North, be based on WGS-84 (World Geodetic Standard of 1984) and mean sea level, and of a valid date. It must also be to a scale that can clearly depict the flight route and other oceanic tracks. Other than that, manufacturers are free to customize charts to whatever preferences they desire.

As far as chart validity dates go, many charts do not have expiration dates; rather that dates published are based upon the measurement of variation. “You may have to go to the manufacturer’s website to see if a new chart is available,” Gribble says. “If you download it on an iPad, they are updated automatically.”

As far as chart validity dates go, many charts do not have expiration dates; rather that dates published are based upon the measurement of variation. “You may have to go to the manufacturer’s website to see if a new chart is available,” Gribble says. “If you download it on an iPad, they are updated automatically.”

The information crews must include on the chart starts with the aircraft’s CLEARED route (reroutes are very common, and many GNE’s have occurred by crews flying the filed flight plan, not the cleared flight plan). The route’s waypoints – coast out, coast in, and lat/long positions – must be clearly marked on the chart using standard symbology. The chart should also include graphic depictions of ETP’s (Equal Time Points). ETP’s are calculated locations where an aircraft would turn around, divert or continue on its route in case of an abnormal or emergency situation. Flight planning services normally provide these points with your flight plan and are usually based on an engine failure, a depressurization event or a medical emergency. If one of these emergencies were to occur, the crew may have to perform a contingency manoeuvre and must try to avoid adjacent and underlying oceanic tracks should a diversion or descent be required. Thus, neighboring oceanic tracks published daily should be included on the chart for situational awareness. Additionally, it’s a good idea to mark decent alternate airports on the chart.

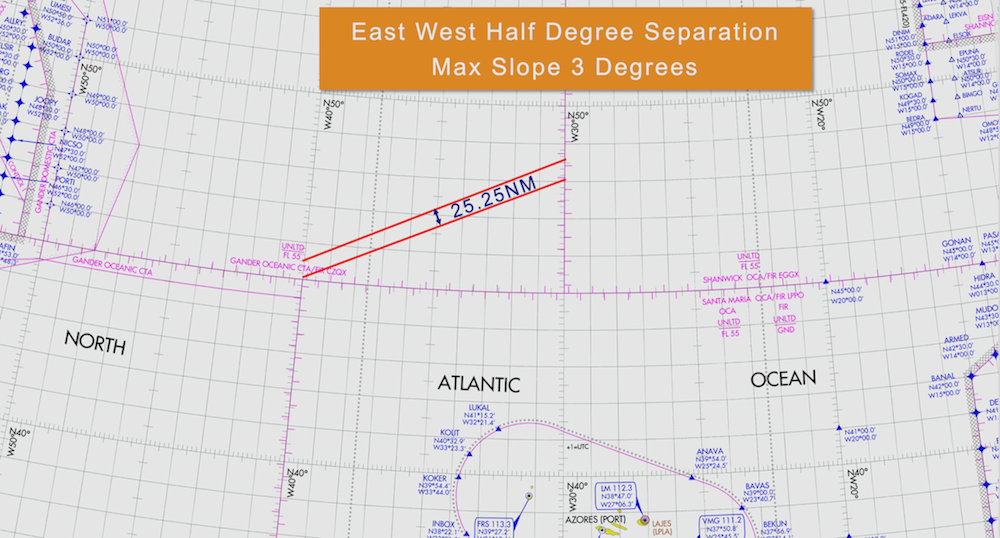

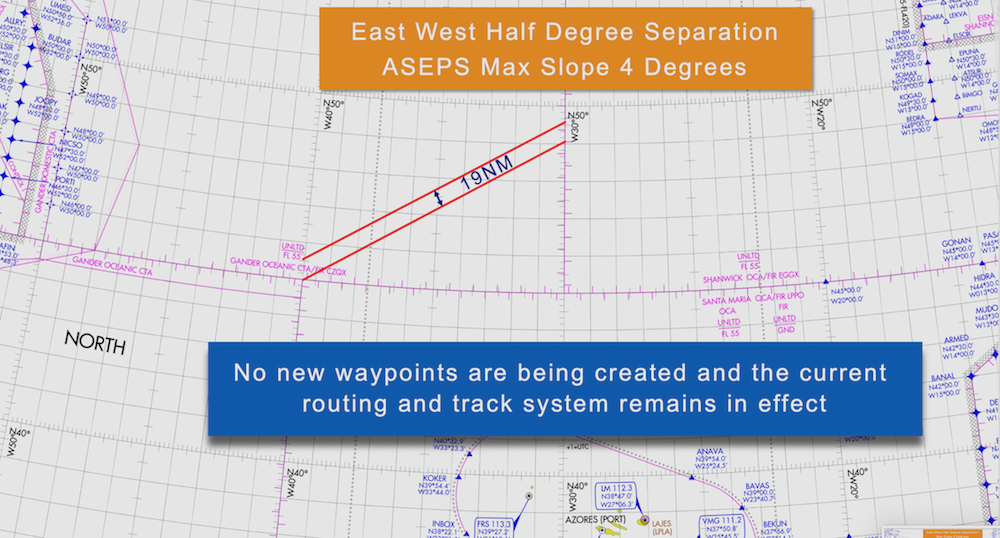

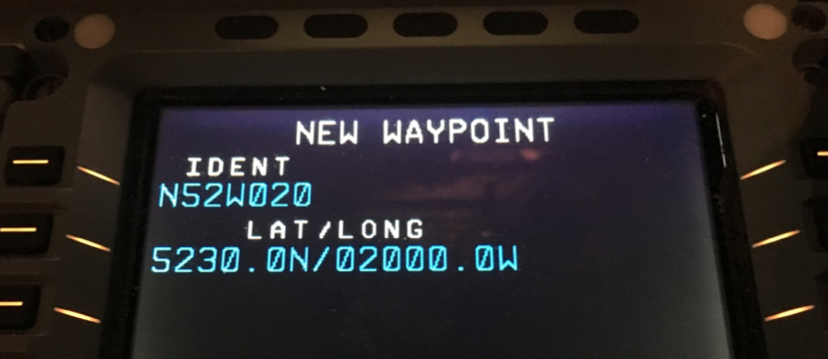

Monitoring your oceanic route is accomplished through a 10 Minute After Waypoint Check. 10 minutes (or roughly 2 degrees of longitude) after crossing each oceanic waypoint, the crew must verify their current position by 1) plotting the current lat/long on the depicted route, 2) computing both magnetic course and distance to the next waypoint and 3) comparing this information to that of the FMS. There are three methods permitted to do this:

- The Plotting or Paper Method

- The Navigational Display Method

- A customized and approved method

The “plotting or paper method” is for aircraft with any navigational configuration. It requires the crew to record the time and plot their present lat/long on the paper chart by using the coordinates from the “non steering” LRNS and take immediate action if the plotted point doesn’t align with the cleared route. The “steering” LRNS – the one coupled and following the autopilot – is then used to verify that the next waypoint is consistent with the cleared route and the autopilot is steering to that waypoint.

The “navigational display method” is for aircraft equipped with an operable FMS. The crew must confirm that the aircraft symbol is on the route programmed in the FMS and set to the smallest scale and checked for any cross track deviation. The crew must take corrective action to address such deviations. And, as with the previous method, the steering LRNS is used to confirm it is headed to the next waypoint on the cleared route. “With the navigational display method, an easy way to record your fix is to have your digitally generated map zoomed in to at least 5nm. Then have your autopilot coupled FMC display the time, lat/long and RNP – the 4 pieces of info you need. Then just take a picture of that with an iPad or iPhone, and that will serve as your recorded plot,” explains Gribble.

And for the “customized and approved method“… if you have created one that has been authorized, we’d love it if you shared! FedEx is one such carrier that has created its own procedures for confirming a reliable fix.

Regardless of the method, it should be spelled out entirely in the company’s operating manuals. Comparing navigation system positioning isn’t the only form of cross-checking. If a reroute is given, good crew resource management is absolutely required when copying, entering and cross-checking the new route.

Along with plotting the position, crews must calculate the magnetic course (remember your private pilot days: true course +/- east/west variation = magnetic course) and measure distance to the next waypoint, both of which are necessary if navigational capabilities of the aircraft are compromised and dead reckoning is required. If you don’t remember how to do these, don’t worry, Code7700 has published a helpful guide on how to do it manually and electronically. There are also several apps and Excel based tools available out there, and many plotting charts have examples to walk you through it.

Ops Spec B036 authorizes navigation over oceanic and remote areas for aircraft having multiple long range navigation systems (B054 if only using a single LRNS) and B037 or 39 dictates whether over the Atlantic or Pacific oceans. “The important thing about B036 is that the operator must spell out in that authorization whether plotting will be accomplished by paper or an electronic method,” explains Gribble. “Part 135 operators must also demonstrate that they have initial and recurrent training programs along with the procedures spelled out. And for the few Part 125 operators, they are required to have a Letter of Deviation Authority.”

Gribble warns, “Operators spend all this time and effort getting LOA’s, Op Specs, and updating manuals and procedures. Then crews never read them again. Keep studying those documents! There are so many restrictions in your LOA’s. Maybe you’re not approved to fly Blue Spruce routes. Unfortunately crews forget what the documents detail, and resort to just flying the way other pilots have been operating. There’s a loss of knowledge.”

He also stresses, “Absolutely use the ICAO (NAT OPS Bulletin 2017-005) or FAA (AC 91-70B Appendix D) issued oceanic checklists! They are excellent resources and cover everything from preflight through arrival at the destination.”

Paper VS The Future

Just over a year ago at an international operators conference there was a presentation for electronic plotting. The presenter spent an hour demonstrating how to perform an oceanic crossing without paper. Although impressive, at that time there was no single app that could perform all the required plotting tasks, and the shear number of additional apps that had to be opened and closed on the iPad to substitute for whatever the main app lacked was astounding. At that point, paper was still king. But in just a little over a year, technology does what it usually does – improved exponentially. And it now looks like there are some apps that can handle all the oceanic plotting tasks, and they’re only getting better.

Mitch Launius, from 30West IP, sees the opportunity for increased safety as these electronic apps continue to improve. “Having another form of redundancy in the cockpit will make things safer in the cockpit. This technology is very new. You could say we’re only at Version .5 – barely out of Beta – but these programs will evolve quickly. This is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s going to happen.”

Mitch Launius, from 30West IP, sees the opportunity for increased safety as these electronic apps continue to improve. “Having another form of redundancy in the cockpit will make things safer in the cockpit. This technology is very new. You could say we’re only at Version .5 – barely out of Beta – but these programs will evolve quickly. This is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s going to happen.”

30West IP has produced several YouTube webcasts, a few which focused on the operational capabilities of some of these apps. “The FAA fully understands the opportunity electronic devices and some of these apps offer for oceanic navigation and they are embracing it – just slowly – as they want to ensure safety of changing procedures.” He points out the requirements for permitting Electronic Flight Bags into cockpit. “If you’re Part 135, you will need the POI’s authorization to receive Ops Spec A061, which would show that an operator demonstrates a change to its procedures.” AC 91-78 Use of Class 1 or Class 2 Electronic Flight Bag is also good resource to check.

However, if an operator is Part 91, there is no authorization required. “Regardless of what you hear, there is no Letter of Authorization required if you are a private operator,” explains Launius. “An inspector would like to see three things, advisory in nature only, however. They want to see that the company’s operating manuals address the addition of EFB and oceanic navigation, that the crew is trained, and that there is a document management procedure in place for recording the crossing.” AC 120-76 Guidelines for the Certification, Airworthiness and Operational Approval of Electronic Flight Bags should be used for guidance.

If transitioning a flight department from paper to electronic plotting might seem intimidating and difficult, Launius disagrees. “It might be much easier than you think. You must update your manuals with a few paragraphs to acknowledge the use of EFB and change in procedures. Then have all the pilots meet and train on the EFB’s. And if you’re a part of an SMS, you’ll just need to show a change in management policy. So perhaps have the pilots meet back up in 6 months and discuss what works and what doesn’t and restructure the procedures as needed.”

“If your department is flying to Europe 2 or 3 times a month, using electronic plotting is going to be very useful,” says Guy Gribble. “But if you’re only flying 2 or 3 times a year, I still believe the ease and affordability of paper is preferable, for now. Some of the newest models of Gulfstream, Globals and Falconjets actually will have the ability of their FMC’s to pull data of its location and wirelessly transmit it to an iPad. Now that’s truly electronic plotting.”

Code7700 has published an impressive article comparing some of the leading electronic plotting apps. Arinc, Jepp FD, Foreflight, plotNG and Garmin are just a few that offer these apps, along with some other flight planning services. Some of the benefits of going paperless is the ability to download both the flight plan and daily oceanic tracks, ETP’s can be updated as can ETA’s, and, through typing or using a stylus, the Master Document can also be downloaded and filled out as the flight proceeds without the all the chicken scratch normally seen on paper plots.

If operators perform many crossings per year, crews will become accustomed to using the apps as well as some of the creative techniques that may be required to compensate for some of the more complicated tasks. Course calculating and distance measuring still seem to be rather cumbersome tasks on most of the apps but operators have come up with some inventive and manageable ways to overcome this. Of course the cost is much greater than the affordable bundles of paper charts, but some of the flight planning companies may provide the app for free if using their services. Ultimately, it will come down to the operator’s needs and the frequency of oceanic crossings.

Thanks to Roger Harr at www.n138cr.ch for the header photo of this article!

As far as chart validity dates go, many charts do not have expiration dates; rather that dates published are based upon the measurement of variation. “You may have to go to the manufacturer’s website to see if a new chart is available,” Gribble says. “If you download it on an iPad, they are updated automatically.”

As far as chart validity dates go, many charts do not have expiration dates; rather that dates published are based upon the measurement of variation. “You may have to go to the manufacturer’s website to see if a new chart is available,” Gribble says. “If you download it on an iPad, they are updated automatically.” Mitch Launius, from

Mitch Launius, from