Update November 2024:

Over two years have passed since we first published this article on EMAS.

A recent report identified that runway excursions are still one the leading causes of business aviation accidents in the US – which has put this valuable technology back on our radar.

It’s pleasing to see that the adoption of these life-saving blocks of crushable energy absorption has steadily continued to increase across the world including recent news that it is coming to Australasia for the first time.

The FAA now reports that EMAS is installed at 121 runway ends at seventy-one US airports and growing.

To date it has safely stopped twenty-two overrunning aircraft carrying 432 pax and crew – the latest, a Hawker 900XP at KTEX/Telluride back in July.

Outside of the US, a number of aviation authorities have introduced or are planning to install EMAS beds to current US FAA standards at airports in countries including the UK, Canada, France, Spain, China and Taiwan.

The adoption of EMAS at airports around the world is beginning to grow.

A first for Australasia

Two promising pieces of news recently emerged from down under in recent months.

New Zealand is installing EMAS at two of its most challenging airports characterized by windshear, short runways and RESAs geographically constrained to the minimum 90 meters (295’). Both receive high volumes of jet traffic.

NZQN/Queenstown is currently in the process of installing EMAS at both runway ends. Work is happening at night and is expected to be completed soon.

Just last week, NZWN/Wellington announced it would follow suit, with major runway safety upgrades. It hopes to have EMAS in action by the end of March.

Wellington – one of two airports in airport soon to receive a EMAS arrestor beds.

A familiar problem remains

If there is any doubt as to the effectiveness of EMAS, consider this. A typical EMAS installation in a 90m (295’) RESA effectively increases its stopping power to the equivalent of 240m (787’) – that’s nearly three-fold.

And yet pilot awareness remains limited. There are no ICAO SARPs for EMAS. And the FAA’s guidance is limited – the only advice for an imminent EMAS encounter is to maintain the extended runway centreline. And once stopped, don’t try and taxi the aircraft.

The reality is that 90m from 70kts looks darn short – and vacant space on either side of the runway makes for an attractive option in the heat of the moment.

Pilots may simply not know it’s there (how often do we brief EMAS?) or act out of instinct. Which means incidents are still occurring where we’re swerving to avoid it.

More on that in our original article below.

Original Article:

Across the US alone, over one hundred runways at 71 airports have a safety critical system fitted to help prevent a major cause of aviation accidents – runway overruns.

It’s called EMAS, or ‘Engineered Materials Arresting System’, which is a technical of way of using drag to safely stop an airplane when all else fails. And better yet, it has your back in all runway conditions – water, snow, ice, you name it. It’s a proven life saver.

But the problem is there are still accidents happening where pilots have actively avoided it, instead choosing to veer off the runway.

Why?

IFALPA recently put out a new position paper which may provide some solid clues. And along with work that others have done, the reasons seem to fit into one of two camps:

- Knowledge about what EMAS is and does.

- In the heat of the moment, pilots just didn’t know it was there.

For such an effective safety system that protects crew, passengers and even those on the ground, is it possible that we’re just not giving it the attention it deserves?

Let’s tackle both camps.

EMAS 101

Dip into the regs and you’ll see that the US FAA requires all airports to have runway safety areas. They are typically 500 feet wide and extend 1000’ past the runway end, and are clear of obstacles in case an aircraft either overruns, or undershoots. Sounds safe, right?

But what if there isn’t enough space? Take KMDV/Chicago Midway for example. It’s not always practical. That’s where EMAS comes into it. It achieves a similar level of safety, only using a lot less room.

In a squeeze – Chicago Midway where EMAS is installed. Courtesy: Chris Bungo

It is essentially a concrete bed (or ‘arrestor pad’) of increasing depth which contains thousands of blocks of crushable material that are designed to quickly slow down an aircraft with little or no damage – likely your nose wheel, and that’s about it.

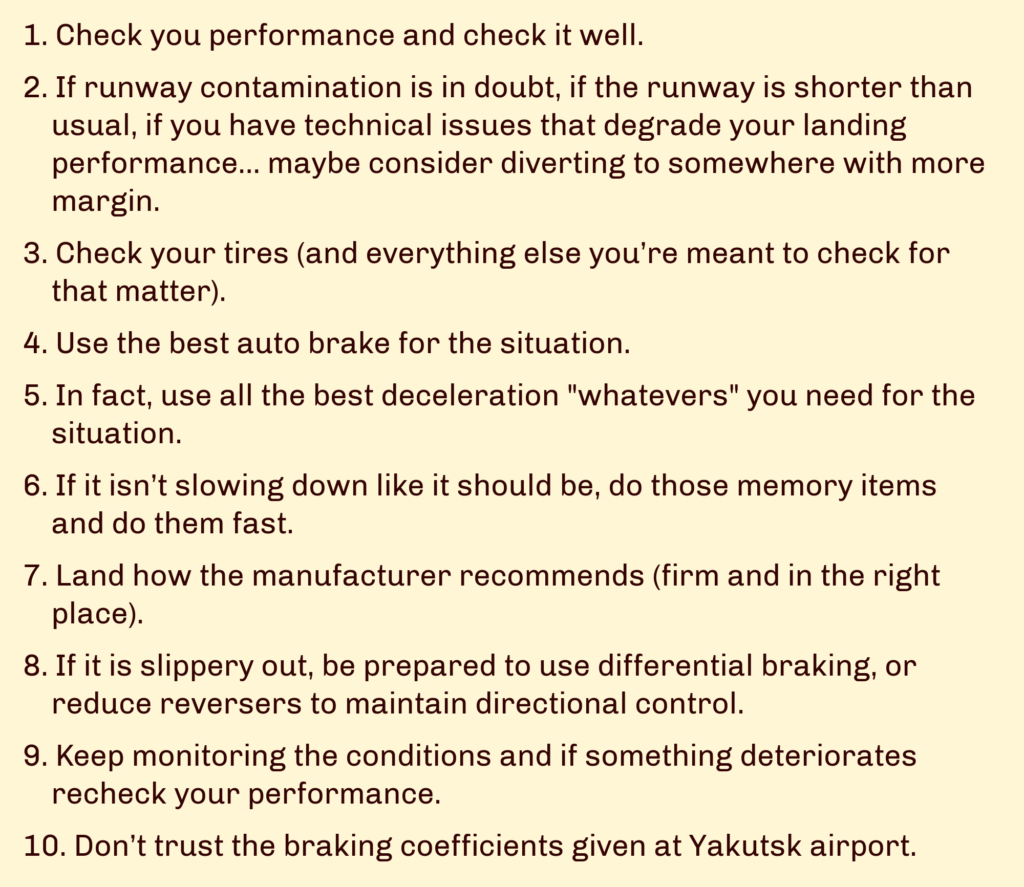

And it works really well too. In fact, it’s so effective it can stop an aircraft travelling as fast as 70kts – which is a good thing as 90% of all overruns happen below this speed.

It’s not even a big deal to replace it – it’s modular. Only the blocks that have been damaged need to be changed out.

Grass and dirt

Some EMAS pads are only 150’ long. When faced with obstacles like trees, buildings, and roads it’s no wonder that the instinct is to avoid ploughing straight ahead.

Instead, the grass and dirt off the side of the runway begins to look like a very appealing option to slow an airplane down. And as the FAA itself once phrased it, ‘there’s a myth that if you take the dirt, you won’t be on the news…’

But the reality is that EMAS will do a far better job and with a safer outcome and less damage.

What about approach lights?

Lights on an EMAS arrestor pad are designed to break away and do very little damage to your ride.

You may not know it’s even there

This is where IFALPA get really stuck in. Some crew actively steered away from EMAS simply because they didn’t know, or forgot, that it was there.

Knowledge is one thing, but you can’t brief what you can’t see.

Yellow chevrons indicate an EMAS arrestor pad, but there is no standardised signage in place for it. Take a look a look again at the list of US airports with it installed – if you operate in and out of any of them, how often are you thinking about EMAS?

If you hadn’t briefed it, would you know it was there?

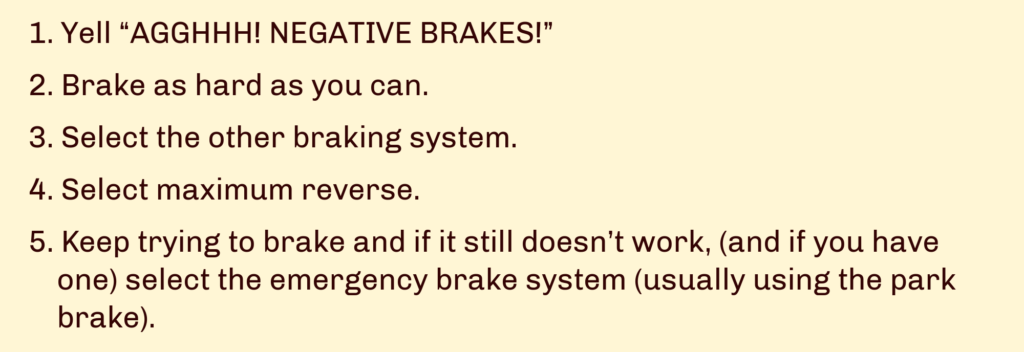

And the story doesn’t end with signage either. What about approach and airport charts? Leading chart manufacturers indicate where EMAS is present on ground charts only. But not on approach charts – the argument is that it won’t fit.

IFALPA has suggested how EMAS might be shown on an approach chart Couresty: IFALPA.

It seems as though the work hasn’t been finished just yet. EMAS is really effective, but as an aircraft departs the runway, there just isn’t enough time to figure out it’s there or not. And that all starts with crew awareness with the tools available when ops are normal.

Regulators in the US and abroad need to be doing more to illuminate this valuable piece of safety tech. At least five hundred lives have already likely been saved because of it.

Knowledge is power

Which is certainly the case with EMAS. Combine both camps, and pilots (myself included) can understand how valuable an obscure sign that says ‘EMAS’ may be, and also know when it is available before you need it the most.

Only then will it live up to its full potential.