The FAA issued a statement on Dec 7 regarding the expansion of 5G networks across the US, and its impact on aviation. It doesn’t sound good – which is something folk have been saying for a while now…

What’s the background?

5G is being rolled out across the US in the form of massive antennas. No issue so far. The problem comes in when they turn them on because they use frequencies which are part of the ‘slice’ of radio spectrum usually reserved for GPS signals. Which means they will probably interfere with those signals, and disrupt the equipment in the aircraft utilising those frequencies.

That equipment concerned are Radio Altimeters which, as we all know, are fairly critical to certain operations. Some big accidents have been attributed to malfunctioning Rad Alts like Turkish Airlines Flight 1951.

Radio Altimeters transmit on frequencies between 4.2GHz and 4.4GHz, while the 5G network will use a C-Band range of 3.7GHz to 3.98GHz.

A larger telecommunications base station.

Why the concern?

The big problem in all of this is the lack of information on how much interference will actually occur.

It is not clear which airports will be impacted or to what degree equipment might be disrupted because it depends on the location and the strength of signals. While the RTCA (Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics) has conducted measurements and found that high levels of inaccuracy and outright failure of Radio Altimeters can be expected when operated near base stations – many of which are located near major airports – until they are turned on it is hard to know…

The FAA also suggested that while issues with RAs are the primary problem, it is unknown what else may be impacted so crew are going to have to be extra vigilant of their instruments, and of passengers potentially connecting to 5G networks while airborne because the impacts are just not known.

What has the FAA done?

The FAA has issued two airworthiness directives, one for aircraft and one for helicopters, in an attempt to enable ‘the expansion of 5G and aviation’ to ‘safely co-exist’.

This is in addition to an earlier Special Airworthiness Information Bulletin issued in November 2021 highlighting the Risk of Potential Adverse Effects on Radio Altimeters.

Let’s take a look at the new directive.

The FAA determined that – “at this time, no information has been presented that shows radio altimeters are not susceptible to interference caused by C-Band emissions” and because they don’t know, they have to mitigate against the possibility that they will be.

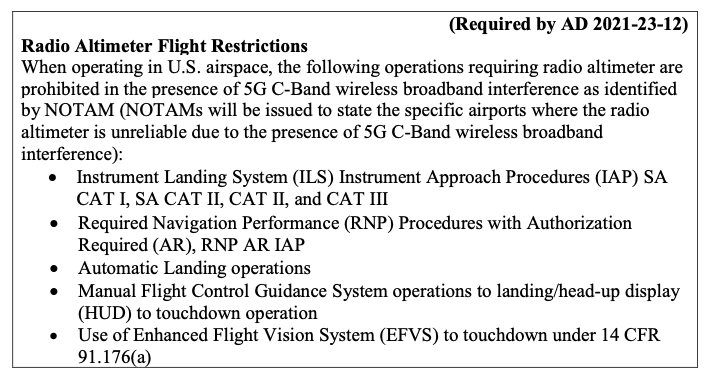

So, AD 2021-23-12 requires the “revising of the limitations section of the exiting airplane/aircraft flight manual (AFM) to incorporate limitations prohibiting certain operations requiring radio altimeter data when in presence of 5G C-Band interference as identified by NOTAMs.”

In other words, you’re going to need to amend your AFM so it takes into account the possible impact of 5G.

The AFM revision will look something like this –

The AFM revision showing RA restrictions

What’s the impact?

In short – possibly a lot, possibly nothing, and the only way to tell is to check NOTAMs. Start checking them now, because operations using the new spectrum started December 5.

The key word in the revision is ‘interference’ because again, that won’t be entirely known until base stations are switched on and reports received. Which puts operators in a tough spot because those approaches that are prohibited (because of interference) are effectively all your precision approaches and means of landing in reduced weather conditions:

- ILS CAT I, II, III.

- RNP (AR) procedures.

- Automatic Landing.

- Manual flight control guidance system operations to landing/HUD to touchdown operations.

- Use of EFVS to touchdown.

Where is the impact?

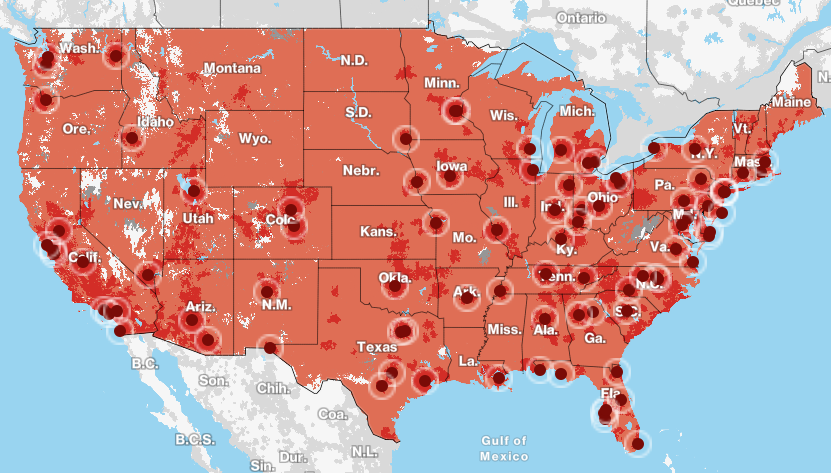

The US currently has around 279 cities, across 46 states, connected to the 5G network. Of course, it is only the base stations in close proximity to airports which will be operating on the C-band at interfering levels that are a problem. The FAA are currently working with telecoms providers to establish which airports will have C-Band base stations near them.

This shows the anticipated coverage across the USA. The magenta is 5G Ultra Wideband, the bright red is 5G Nationwide, and the pinkish/orangey red is the current 4G LTE coverage.

Map of 5G coverage

It could be a worldwide problem

The issue is not necessarily restricted to the US. 5G is growing globally, with China equally far ahead in their implementation of it, which raises concerns of where else this might pose a potential threat.

Thankfully some countries, like Canada, have opted to prevent or restrict services near major airports, at least until further data is received.

What you need to do.

- As an operator, you will need to ensure your aircraft are compliant with the new directive, so read AD 2021-23-12 and ensure you update your AFM when required.

- Right now, the biggest thing to do is to check NOTAMs.

- Base stations are still being activated, and the interference levels due variable power levels and locations means it is not clear where or what the impact will be. NOTAMs will therefore be issued for specific airports confirming the restrictions for them, as and when this is known. And this could change daily.

- Staying updated on the situation at airports you operate into, as well as encouraging crew to review the weather and alternative approaches in case they become required is critical.

- Review the function of radio altimeters on your aircraft and understand the implications to capability and performance of malfunctions.

What else can you do?

You can write in and express comments, written data, views and arguments on the directive to the FAA. Ensure you title the correspondence with this – “Docket No. FAA-2021-0953 and Project Identifier AD-2021-01169-T”

You can Email this feedback to operationalsafety@faa.gov. Alternatively, you can send via Fax: 202-493-2251 or Post: U.S. Department of Transportation, Docket Operations, M-30, West Building Ground Floor, Room W12-140, 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE, Washington, DC 20590.

You can also request further information from Mr Brett Portwood, Continued Operational Safety Technical Advisor, COS Program Management Section, Operational Safety Branch, FAA, 3960 Paramount Boulevard, Lakewood, CA 90712-4137.

Any interference should be reported to the FAA to assist them in building up a better picture of the impact and safety concern.

You can also follow AOPA’s work on 5G as they continue to monitor and ask the FAA to address the situation urgently.